Key concepts for this article:

- DOB2: Never-Ending Customer Improvements and Personalization

- Economies of Scale: Geographic Density (CA13)

***

As mentioned in Part 1, I recently visited Zé Delivery in Sao Paulo and toured their growing facilities with CEO Rudolfo Chung. Zé Delivery is a Brazilian beverage delivery app launched by global beer giant AB InBev. It has had rapid adoption and is currently being expanded to all of Latin America. I talked about my visit in Podcast 139 (How AB InBev and Zé Delivery Are Changing Ecommerce in Beverages).

As a business, Zé Delivery is a fairly straight-forward mobile app that lets consumers order lots of types of alcohol and get them delivered in 15-20 minutes. Its consumer value proposition is a wide selection of beer, wine and spirits that is cheap, cold, and fast. That’s a pretty good pitch for a mobile app.

- As a subsidiary of the world’s largest beer company, Zé Delivery can sell a big selection at a good price.

- They can deliver fast because they have lots of delivery stations plus AB InBev’s big fulfilment network. Fast delivery makes it convenient, which consumers love and usually induces demand.

- And the beverages arrive ice cold, which consumers like. Zé Delivery has big refrigerators in its delivery facilities that are kept really, really cold.

That’s a simple value proposition. And it really works. By every measure, start-up Zé Delivery has great product market fit. And they were growing fast even before Covid spiked their demand.

As mentioned in Part 1, my assessment of this early version the business is:

- It’s a popular service with good product market fit. The numbers are big and have grown really fast.

- The business has a serious barrier to entry against digital natives, which cannot easily replicate their physical infrastructure and their COGS (because of their tie to AB InBev).

- However, this beverage delivery service can probably be replicated by other large retailers (such as supermarket chains and convenience stores). They also have significant distribution scale and purchasing power. But Zé Delivery was the first mover and they are moving fast.

That’s my basic take.

In this article, I really wanted to point out two interesting lessons in digital strategy from Zé Delivery.

Lesson 1: DOB2 Never Ends for Most B2C Mobile Apps

As mentioned, the Zé Delivery app is still pretty basic right now. Its an ecommerce retailer with lots of alcohol types and expanding delivery. They are doing some personalization. And there are some offered bundles. That is pretty standard for an ecommerce mobile app. If this is all they do, they will become vulnerable to imitation by supermarkets, convenience stores and other large retailers.

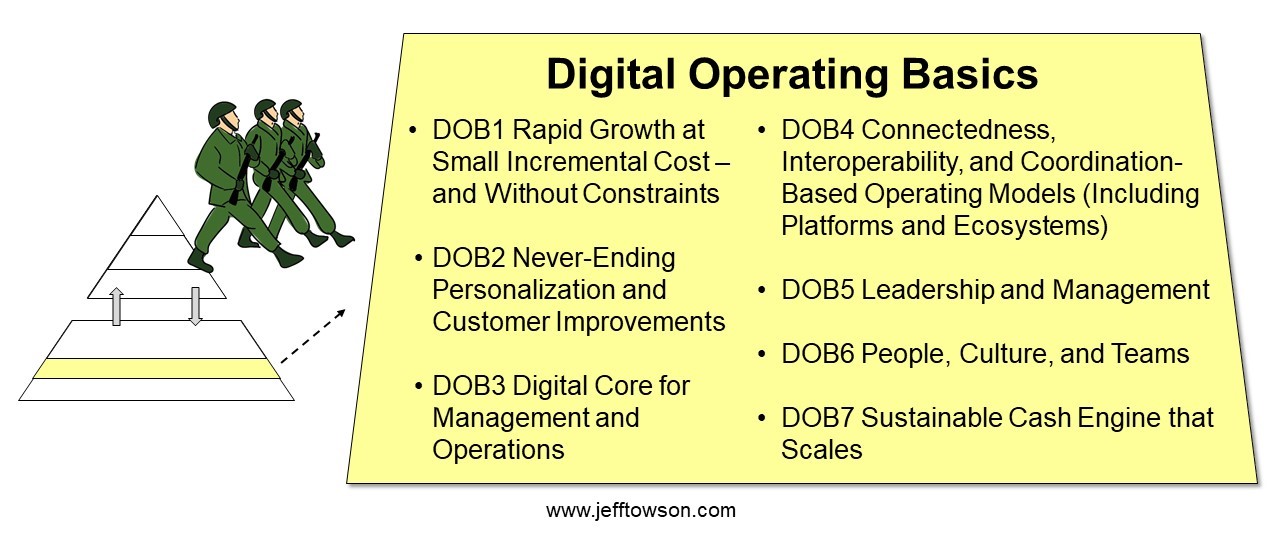

Zé Delivery needs to lean into Digital Operating Basics 2 (Never-Ending Personalization and Customer Improvements). That’s how they stay ahead of the competition. They need to do a never-ending process of experimentation and innovation on the customer experience (including personalization).

And this requires expanding from just selling beverages to being an occasions and events service. That focuses them more on experiences, where there is far greater room to innovate and improve. You focus on an individual’s happiness. And on how to enhance the interactions between people at events. If you look at Zé Delivery this way, it gets a lot more interesting as a digital company. And the company can increasingly specialize its experiences and operations. That would make them more valuable to customers. And much harder to copy by supermarkets.

The need to focus on DOB2 is so common for so many B2C mobile apps. Unless you have network effects or some other massive competitive advantage, leaning into DOB2 becomes essential.

And here’s the twist. Even if you do have network effects (such as in the case of Ant Financial), you often still have have an imperative to focus on DOB2.

***

In Part 1, I wrote about the network effects trap. My point was that network effects can work just as fast in reverse. For example, if merchants stop taking American Express cards, they become less valuable to consumers. Then fewer consumers carry them. And they become less valuable to merchants. And so on. We can get a negative feedback loop.

The weakness of network effects is they make you highly dependent on keeping activity on your platform. If you start to lose consumers or merchants to a competitor, you can fall into a reverse network effect. So you need defenses against competitors stealing your customers. A platform losing customers is like an airplane losing altitude. The pilots get frantic.

Recall that network effects are “demand side economies of scale”. And just like “supply-side economies of scale”, they only work if there is a scale differential between the market leaders and most competitors. You need to be bigger for this to work (i.e., a scale advantage). Maintaining this scale differential is easier if the market is circumscribed. Meaning there are no lateral or related markets or services a competitor to get large in. You want to be the biggest hospital in an isolated mountain town.

If also helps if there is slow growth. That limits the space for another company to grow. If a competitor wants to match your scale, they have to steal your customers. They can’t just grow with the market. This is why network effects (and economies of scale) are stronger if there is also some form of customer capture (like switching costs). It makes customers harder to steal.

This situation (a scale differential in a slow growing, circumscribed market) is usually not the case for digital services and mobile apps. These markets are often high growth. And digital services are good at moving across industry barriers. That’s a problem for network effects businesses.

Ant’s solution to this problem is to lean into DOB2. In fact, the central strategy of Ant financial and Alibaba is to continually improve the user experience. They talk about this all the time as their primary strategy. That’s good business. It’s also how they protect their network effects in high-growth markets with fuzzy boundaries. These companies are continually adding value to the user experience (which includes consumers, content creators and merchants / brands). Basically DOB2 is their primary defense for the network effects.

That is lesson #1.

Lesson 2: Economies of Scale in Geographic Density (CA13) Is Underestimated in B2C Services

I have written a lot about how Meituan and Grab are both focused on achieving economies of scale based on geographic density (CA13). This is an increasingly important competitive advantage in B2C services (like Zé Delivery). Really in any service where delivery and logistics are combining with machine learning to achieve tech-driven cost efficiencies.

Here is my standard definition for CA13: Geographic and Distribution Density.

“Geographic density is a competitive advantage that results from having greater customers, volume, nodes, and/or routes within a geographic area than a competitor. For distribution businesses, this can result in:

- Lower costs

- Greater coverage

- Faster distribution times

Superior geographic and distribution density can be an advantage of the larger players. It’s a scale advantage.”

This one can be kind of confusing.

When people think about economies of scale, they usually think of fixed costs (which is definitely one type of economies of scale). Having greater scale means your fixed costs (like IT spending and R&D) drop as a percentage and you get increasing operating leverage. But geographic density is a scale advantage that is usually a variable cost. With this scale advantage, we usually see lower delivery fees per order. It’s a variable cost.

For food delivery (Meituan, Grab), we can see a required time and cost for each activity within a typical order.

- Riders go to lots of different restaurants. When receiving an order, they move around within a 7-10 kilometer radius from their location. They can be close or far from a specific restaurant. And they are often going to different places to pick up orders.

- At the restaurant, the rider usually waits while food is being prepared. Or the restaurant is waiting for them.

- They eventually pick up one or more orders from that specific restaurant.

- They then go to deliver the order(s) to one or more homes, which can be anywhere within a fairly large radius.

- At the point of delivery, they often must wait for the customer. Especially if they are getting paid in cash.

- They then accept another order and go off to another restaurant,

And that is the simple version. Drivers can also pick up orders at other restaurants as they are in the process of delivering already picked up orders.

Now, think about how the time and cost of each activity changes with:

- Increasing customer density in a geographic area. Doesn’t that make the trips shorter? Cheaper?

- Increasing restaurant density in a geographic area. How does this decrease time and cost? It certainly increases the options for consumers.

- Increasing order volume in an area. How does this change the batch size for a driver on a trip? Are they carrying 1, 2 or more orders? How does that change the optimal delivery route?

In the simplest version, a company with greater geographic density of orders has drivers that are closer to their next restaurant when they receive an order. And the spatial distances for pick-up and delivery decrease with increasing orders, restaurants, customers, and driver density.

But the routes the riders take are not fixed. Riders can change the streets they take to decrease the time to reach the restaurant and then the customer. And as riders are increasingly combining different orders (batch size), they can then optimize their routes for a particular order combination. That’s why machine learning and technology are an important part of this competitive advantage.

Overall, what we should see with increasing geographic density and other tech-driven cost efficiencies is:

- Decreasing average delivery times.

- Decreasing average delivery costs.

- Increasing geographic coverage for both customers and restaurants.

For example, Grab talks about targeting three metrics to increase driver productivity with increasing scale.

It’s all pretty cool.

Now, think about how this competitive advantage changes for beverage delivery.

First, Zé Delivery is not a marketplace (yet). It is a pipeline business that provides a service. It has economies of scale in purchasing power (by AB InBev) and a big supply chain (lots of warehouses). But it is not a marketplace with network effects.

I visited several Zé Delivery distribution hubs in Sao Paulo. Some are co-located with AB InBev warehouses. Others are more specialized fulfilment centers. And then there are partner distribution centers blanketing the smaller neighborhoods of Sao Paulo. Here is a one of the specialized fulfilment centers.

For these, you have delivery guys on motorcycles going back and forth from one center. They are not migrating across town serving lots of different restaurants. They stay local in one part of town and work out of one distribution center. This means they know the neighborhood well and do lots of fast trips. There is much less need for machine learning to do batching and route optimization.

There is also very little waiting time to pick-up. The center works very fast assembling the bagging the orders. It is not tons of small restaurants doing food preparation. Here are orders being prepared.

And here are delivery guys waiting for the orders.

So, what are the advantages of having greater geographic density than a competitor in this type of model?

- Greater order density is key.

- This requires more distribution points.

- Distribution centers will have greater efficiency.

- Distribution centers will be closer to customers – being both faster and cheaper.

- Distribution centers will have greater ability to combine orders.

This linear distribution (not marketplace) model is a lot more about opening lots and lots of facilities all over town. Both directly and with partners. And then specializing those facilities, their technology and their drivers for cold beverages.

This raises interesting questions.

- Are we going to see increasingly specialized distribution and delivery services? Some for beverages? Some for hot food? Some for pharmacy?

- Are we going to see a combinations of distribution for marketplaces (like Grab) and for specialized distribution (like Zé Delivery)? What if iFood (the Grab of Brazil) and Zé Delivery started to coordinate their services?

- In which B2C services models does greater geographic density have the most power?

Note: here is a distribution point for iFood. Note the order complexity on the screens.

Anyways, it’s a really interesting situation. And that’s lesson #2 for today.

Thanks for reading. Cheers, Jeff

And for fun, here are some more pictures of murals in Sao Paulo.

——–

Related articles:

- Zé Delivery’s “Wow” Experiences vs. Ant’s Sustained Innovation Imperative (1 of 2) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- Why I Really Like Amazon’s Strategy, Despite the Crap Consumer Experience (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Big Questions for GoTo (Gojek + Tokopedia) Going Forward (2 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- Why Netflix and Amazon Prime Don’t Have Long-Term Power. (2 of 2) (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- DOB2

- Economies of Scale in Geographic Density

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Ze Delivery

- AB InBev

- iFood

——-

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.