This week’s podcast is about Amazon’s competitive advantages. We can see clearly growing moats in ecommerce. But increasing competition is revealing the lack of defenses in video streaming. Netflix has the same problem.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

——

Related articles:

- Why I Really Like Amazon’s Strategy, Despite the Crap Consumer Experience (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Big Questions for GoTo (Gojek + Tokopedia) Going Forward (2 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- GoTo Is Going for an “Ultimate B2C Marketplace” in Indonesia. But Alibaba Couldn’t Do It in China. (1 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Economies of Scale: Purchasing Economies

- Economies of Scale: Fixed Costs

- Digital Operating Basics

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Amazon

- Netflix

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash

——-Transcription Below

:

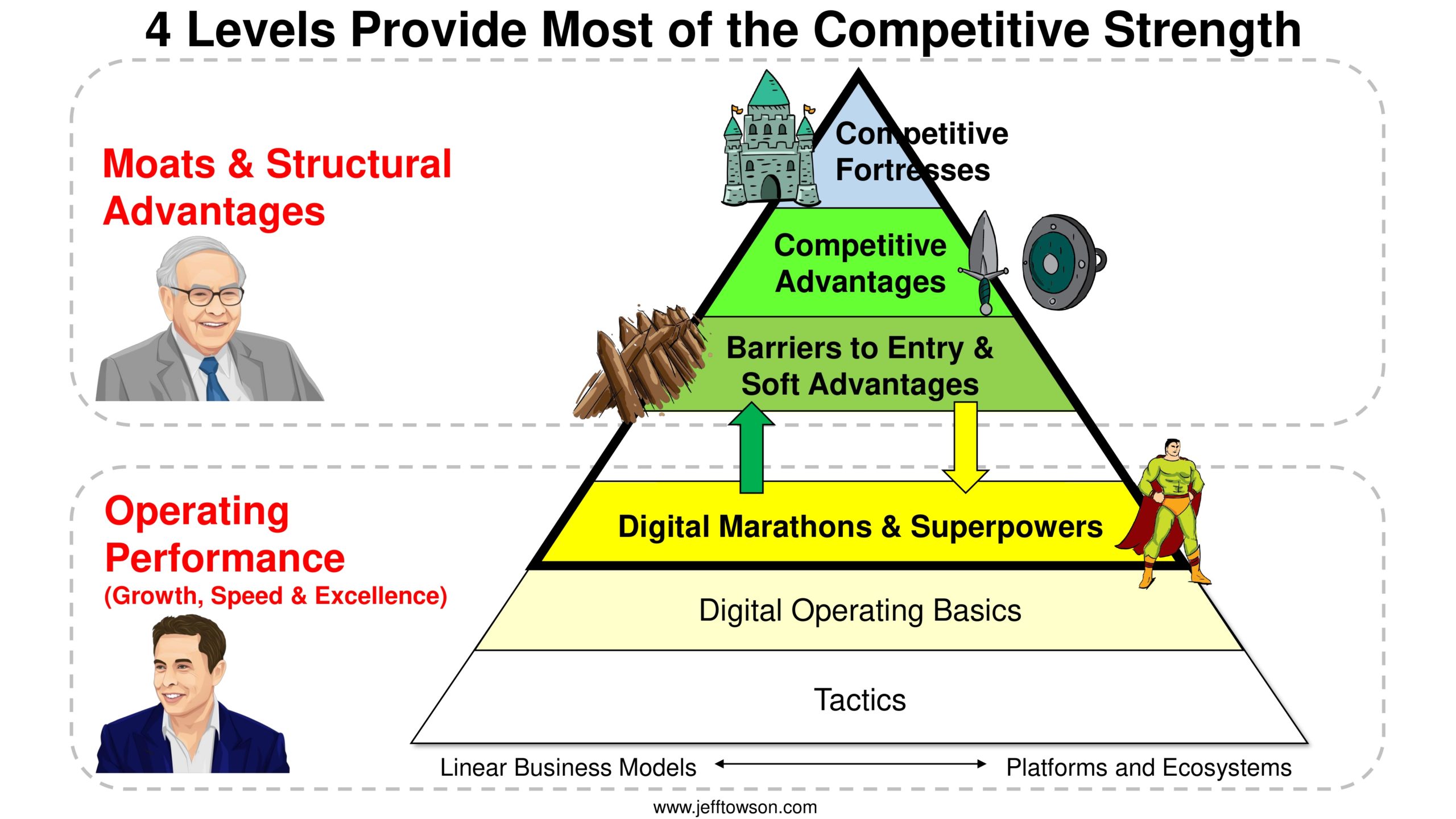

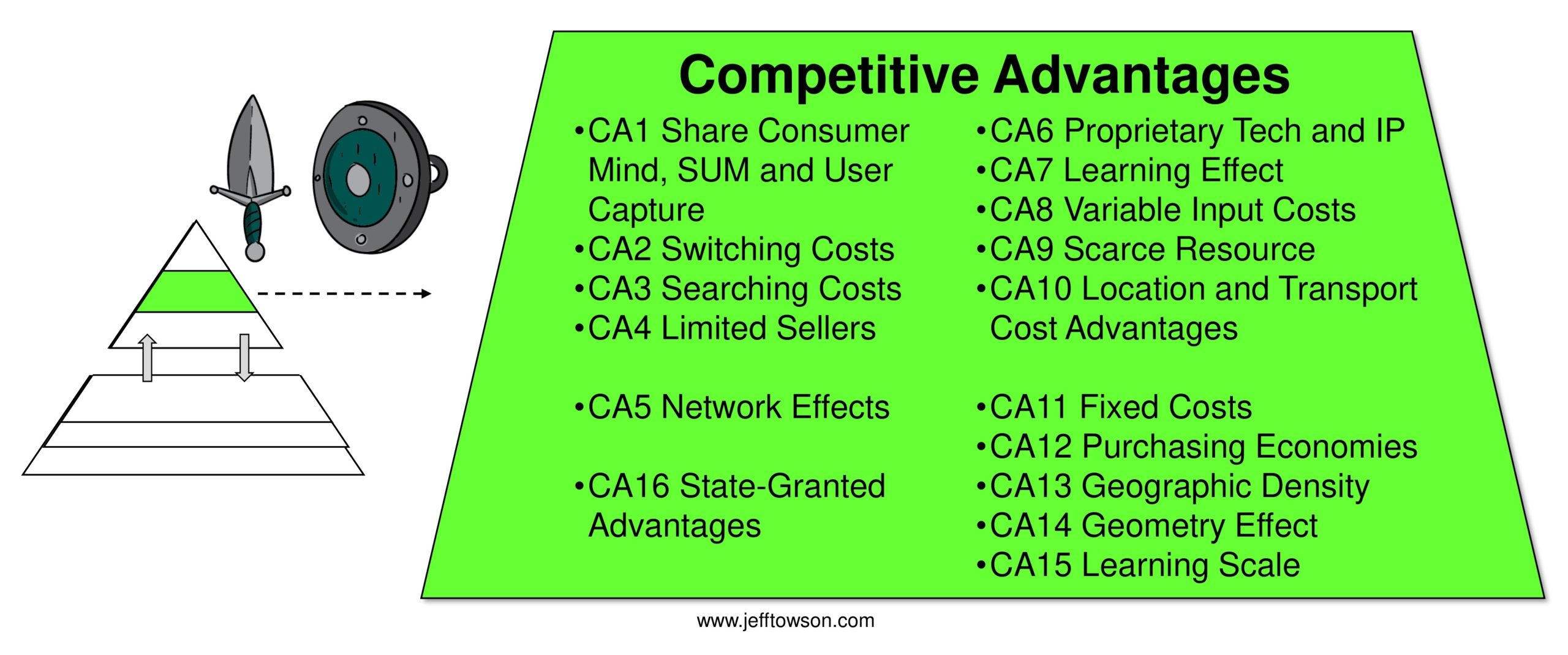

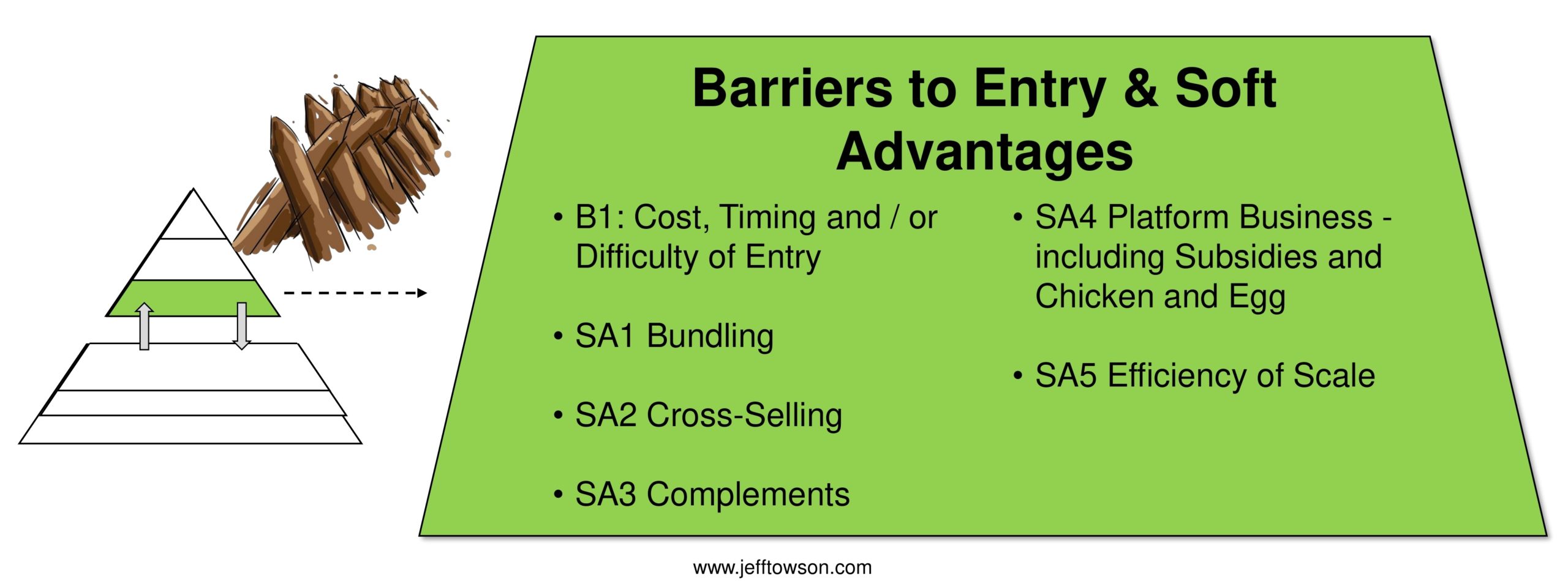

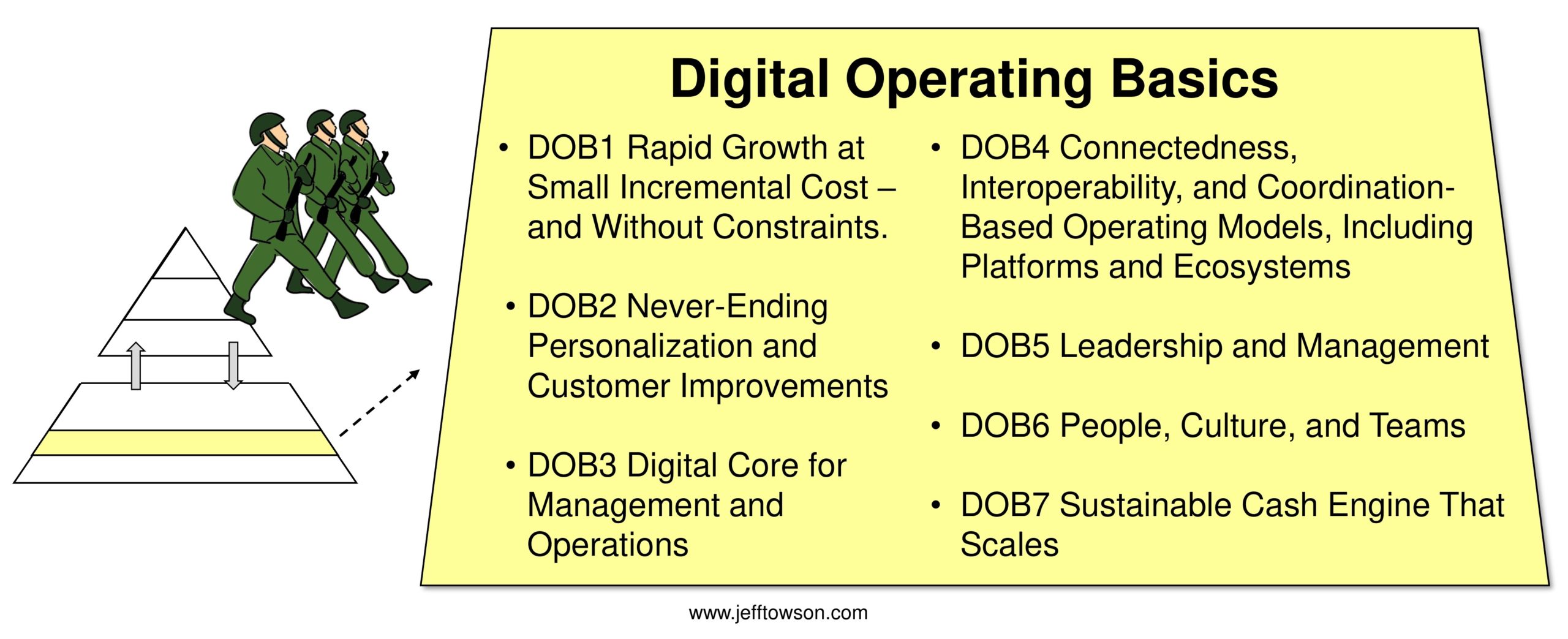

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, why Amazon is getting stronger in e-commerce but weaker in video? Just like Netflix. And yes, I guess a disclaimer, yes, I’ve changed the name of the podcast again, which is what the second or third change in a couple weeks now, because I haven’t really been able to find one I thought was good or easy to say or… easy to remember. So I just kinda kept it simple. I think this one’s probably fine. Tech strategy focused on the best digital companies in Asia and the US. That’s a nice simple approach. So I think we’ll probably go with that. And I think this is actually a pretty good example of that question because tech strategy, okay, that’s my area. Amazon, big company, important in the news a lot right now because the… price has gone down significantly as has the price of Netflix. The share price has gone down dramatically and it really, you know, there’s a lot going on with that obviously, but you know, at the center of that is a really cool tech strategy question, which is, look, which of these business models is going to get stronger, which is going to win and which one is not as strong as people think it is. And Amazon’s a really good example of that, because I think the e-commerce business is stronger than is commonly appreciated, and I’ll explain why. And at the same time, the video business, Amazon Video Prime, and similar to Netflix, really, I think this has been misjudged, both of these companies, or at least those businesses. have been seriously overestimated for a long time. I don’t think that business model, the Netflix over the top streaming bundle, I don’t think it’s nearly as strong as people have thought. And there have been books written about this, like all of the power of Netflix business model. I’ll give you my take on it. I think, I don’t think it’s that strong. I don’t think it’s ever been that strong. I just think it’s been a bit covered up for a while. And now we’re seeing it play out. So I’ll give you my take on that. And I think that’s some good tech strategy stuff within that. So that’ll be the topic for today. And for those of you who are subscribers, I’ve sent you a decent amount on Amazon. I’m gonna send you another article in the next day, which will basically be sort of a strategic breakdown of Amazon video versus Netflix versus the e-commerce. So I’ll give you more detail on this because there’s actually kind of a lot there. but this will be a bit of a shorter takeaway version. And let’s see, for standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing a website is investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. Abuse and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the content. Now, as always, I’m going to sort of start out with the key concepts. And I think if you understand the key concepts that matter, the difference between why e-commerce is smarter than people, I’m sorry, is better than people think it is and why Netflix and Amazon video are weaker, I think it becomes very obvious if you frame the question, right? Which is the whole point of having this sort of concept library, which is on the website. You know, if you have the right framework in your brain from the beginning, it really, these things can often be very easy to take apart. If you don’t have the right framework, it can get muddy, it can get confusing, it’s hard to see through all the facts and data and all that. So if you ask the right question, if you use the right framework, sometimes this is very easy to just sort of take apart. And often, which I think is the case today, you can see stuff that other people are getting wrong. So, you know, choose, that’s kind of why I’ve laid out the, you know, the course this way is, you know, there’s a big library of companies and there’s a big library of concepts. And you sort of try and fit the right concept to the right question. And sometimes it really does sort of open up, and that’s, you know, it happens on a regular basis, not all the time, but sometimes, and I think that’s the case today. So two key concepts for today. I’m actually gonna give you three or four, but the… Two of them that matter are economies of scale based on fixed costs, which I’ve talked about before. I’ll go through that in detail. And the basic, I mean, this is when people talk about economies of scale, you know, company A is bigger than company B and bigger can be by revenue, by spending, by activity, by demand. But because of a large differential between company A and company B, certain fixed costs, usually marketing, R&D, IT spend, you get a cost per unit, cost per activity that is lower than a competitor because of your scale differential. And usually when people talk about economies of scale, that’s what they’re talking about. Although there’s actually four or five different types of economies of scale I look at, but usually people tend to be talking about fixed costs. you know that the standard factory example my factories twice as big as your factory because i have more volume therefore my cost per widget is lower because we spread out the cost structure and whenever you hear about netflix over the last ten to fifteen years whenever people talk about the power of netflix to competitive strength they always point to economies of scale in content spending Netflix spends more on content, you know, 10, 11 billion dollars per year on in-house production of content or acquiring content from let’s say a studio and then because they have a bigger user base, a bigger subscriber base, they can spread those costs out of over more subscribers and therefore they’re cheaper per subscriber. That is like the go-to explanation for Netflix. and Amazon Prime video is pretty much the same business model. I don’t think that’s actually true. I think that’s a first level sort of thinking of this. But if you, anytime you take one of these concepts, network effects, economies of scale, switching costs, when you start to apply it to a specific company, you realize that these things are very different depending on what company you’re talking about, there’s a whole lot of different types of network effects. There’s a whole lot of different types of economies of scale. There’s a whole lot of different types of switching costs. And when you move to the second level or third level of thinking, that’s when you can see, oh, this, you know, it turns out Uber doesn’t really have network effects that are so powerful. Oh, it turns out that Netflix doesn’t really have economies of scale and fixed costs like everyone thinks it does. It’s the second level, third level thinking where you see the differences. And that’s what I’ll talk about. I don’t think that’s where their strength has been. I don’t think that’s a big deal for them. It’s okay, it ain’t awesome. And I’ll explain why I think that’s not the case. But when you apply fixed cost economies of scale in the e-commerce business, which is building warehouses, it really does play out, but it doesn’t play out in content creation as a fixed cost. So I’ll talk about why that is. So that’s sort of concept number one for today, economies of scale in fixed costs. Concept number two for today is what I’ve called the digital operating basics. It’s level four in my six levels of competition meets digital. The digital operating basics are, let’s take a traditional business, whether it’s logistics, retail, media, healthcare, manufacturing, and let’s start to digitize the operating activities. and a lot of companies are going through this. Media and communication went down this path very early on. Retail and e-commerce also moved fairly quickly, but a lot of industries like manufacturing and healthcare, they’re still digitizing their core operations right now. And I don’t consider any of this to be a real competitive strength. I just think this is sort of, look, this is the way all companies are gonna be. And if you got there a little earlier than others, it looks like you have all these tremendous strengths. When the truth is, you’re just doing the digital operating basics, all companies are gonna do this. And when we look at the, I’ll give you kind of the so what now, which is when we look at e-commerce on Amazon, what we see are competitive advantages and barriers to entry that are getting stronger over time. That’s where the power is. Level two, level three. competitive advantage, barriers to entry. When we look at Netflix and Amazon Video, most of what we’ve been seeing is digital operating basics, creating a streaming bundle, packaging lots of content. That’s not really that great of an advantage long-term. They just kind of got there first. And when you put the streaming bundle, the over-the-top business model against a traditional cable company, it looked very strong. But when you put that against 10 other streaming companies, you realize they all do those basics. And that sort of fades over time. And what you’re left is, okay, they’re doing the digital operating basics well, Amazon Video, Netflix, Disney’s doing them. And that was powerful against a cable company, but now all the companies are operating this way. Do they have a competitive advantage against those? And the answer is mostly no. Mostly what we’ve been seeing is Amazon Video and Netflix did the digital operating basics first. They were an early mover and it was particularly powerful against traditional incumbents like movie studios. But when they go head to head with 10 other streaming companies, they don’t have that many strengths. And we’re seeing that play out in their churn rate, in their decreasing growth, in their increasing spend on marketing. This doesn’t look like a dominating company against other streaming companies. It looks just like a decent competitor. And that’s kind of the so what of today’s podcast, but I’ll go through the details. Okay, so those are the two ideas for today. Economies of scale and fixed costs, digital operating basics versus a traditional non-digital business versus a similar business model. It plays out differently. Okay, so those are the two concepts. Let me just kind of go through the basics. Now if you look in the show notes, you’ll see my standard six levels of digital competition and within there I’ve broken out levels two, three and five, which is competitive advantages, barriers to entry and digital operating basics. Each one of those levels has a list, a checklist under it and you can just run the checklist and I’ve put them all in there and I’m just going to talk through them. So We look at Amazon’s e-commerce business, which I’ve talked about before, which is a combination of a retail business, which is a linear business model. We buy the goods from suppliers, we put them into our inventory, we put them into our warehouses. They’re under our cost of goods sold. When we sell them, we make a margin. Linear online retail business. It’s Walmart, but online for the most part. Fine. In addition to that, they have a marketplace business model, which is a platform business model. We’re serving merchants and we’re serving consumers. And in this case, obviously we’re not taking the inventory. We’re just enabling interactions. It’s a marketplace platform. And they make money by transaction fees. They make money increasingly by advertising fees. That shows up under their service revenue. The retail business shows up under their product revenue. If you look at their income statement, you’ll see them broken out. They’ve got big revenue under both, revenues for services, revenues for products. However, under the services revenue, they’ve also got their AWS business and they’ve got, so it’s a bit mixed together if you look at the income statement. But on the e-commerce business, you basically have two types of revenue, services, which is the platform business model, and then retail, which is the product revenue. Okay. So we just run the list. We start at level two, which is competitive advantage. I’ve listed 15 types. You can look at the show notes. You’ll see the slide I’ve listed them all. And you can sort of just run the list and the left side of the list, these are basically demand side advantages, demand side competitive advantages. CA1, share of the consumer mind, CA2, switching costs, CA3, searching costs, CA4, limited sellers in the long term. CA5 network effects, and then we get to government. So, you know, the first five are really about demand side power. And then you move to the left side, I’m sorry, the right side, and those are basically cost supply side competitive advantages. CA6, proprietary technology, CA7, learning effects, CA8, variable input. You just run the list. And economies are scaled there. And, you know, my book series, Motes and Marathons, basically goes through all of this in excruciating detail. Book number three goes up in, I think on Tuesday, it goes live on Amazon if you’re curious, but I’m working my way through all of this. Anyways, we can just run the list for Amazon’s e-commerce business, which includes the retail business and the platform business model. And it’s pretty good. They have share of the consumer mind, which is like… You know, habit formation, people buying cigarettes every day as a share of the consumer mind because it’s chemically addictive, people logging in to TikTok all the time. It’s a habit. People checking their WhatsApp all the time in their email. You know, that share of the consumer mind effect, there’s not a lot going on with Amazon e-commerce there. People are going on Amazon the same way they go to Walmart. They’re not checking in 10 times a day. But if they need stuff, they’ll go. That sort of bucket of strength is much stronger in China with Alibaba. Amazon’s pretty weak in that regard. Switching costs, not really. There’s a little bit. You can do loyalty programs and gamification, but it ain’t knocking the socks off. Switching costs do tend to be more powerful on the seller side, merchants and retailers. So when you look at the platform side of Amazon e-commerce, they’ve got some pretty good switching costs there, but not on the consumer side. And then limited sellers, long-term supply, demand, but I’m not gonna go through all of these. Those are all fine. None of them knocked me over. The one that jumps out at you is network effects. Amazon’s marketplace has serious network effects going, and that is demand side economies of scale. Amazon’s marketplace, 2021, was in 19 countries. $390 billion worth of GMV. You know, millions of sellers, they have a massive marketplace for e-commerce with big, big network effects. You know, everything you could possibly, I mean, Amazon’s the everything store. If you’re a consumer, everything you could possibly want is there. If you’re a seller, you have, you know, hundreds of millions of consumers. There is a massive network effect. That’s their big lever on the demand side. They have some other stuff going on too, but that’s the big one. Um, okay. Fine. That would be on my short list of where the, the power of their e-commerce businesses on the demand side. we move to the supply side, the two that jump out at you, purchasing economies and economies of scale and fixed costs. So if you want the quick and dirty explanation of the competitive power of Amazon e-commerce, it’s network effects, purchasing economies, economies of scale and fixed costs. Fixed costs are mostly fulfillment and IT. Okay. Purchasing economies that’s on the right side of the list. It’s number to do to do to do CA 12 Now this is just Amazon acting like Walmart. They’re a massive retailer They go to all the suppliers most of which are in China and places like that and they negotiate deep discounts because they’re buying so big And that gets them a lower price. So it’s an economies of scale Argument and the purchasing economies is a type of on economies of scale This is only valuable if you’re bigger than your competitor. And Amazon e-commerce is bigger than the vast majority of their rivals. There’s a couple that can match their purchasing power, like Walmart, Carrefour, but the vast majority of retailers can’t get anything like the cost of goods sold they can. So they get power on purchasing economies, they can pass that on to consumers as lower prices. That’s the go-to competitive advantage for a lot of traditional retailers. Amazon has it in their retail business. Okay, fine. The other one, economies of scale in fixed cost. Now Netflix, I just said, their big fixed cost is IT spending and content creation, in-house production. This is their 10 to $11 billion. of making all these television shows and movies every year, the vast majority of which suck. I mean, House of Cards was good, and there’s a good one every now and then, but most of them are pretty bad, which is what a lot of people are talking about right now with their falling share price. Okay, the fixed cost for a company like Amazon E-commerce, it’s IT, spending, right, all those servers, and it’s fulfillment, it’s all of those warehouses. Now, their delivery cost, that goes under variable costs. So this is a fixed cost. It’s warehouses, it’s robotics, it’s automation. It’s everything that they sort of call infrastructure, which is actually the same term that Alibaba uses. They talk about the new infrastructure of commerce, which is really IT spending, fulfillment spending, and then physical retail spending. For Amazon, it’s just the first two. That is them building. you know, infrastructure that covers country after country that lets them do fulfillment and web services and all of that. Okay, that’s their massive spending and they are outspending everybody when you look at their fixed cost spending in this area. The latest numbers I looked at, you know, their logistics spend, their tech spend, you’re talking about 35, $40 billion a year they’re spending. Their biggest competitor, Walmart is about 10 billion. So they’re outspending Walmart by a factor of three. And then you go to their next biggest competitors like Home Depot and Target, and it’s two to three billion. So they are just flooding money into this. That’s a strategic move, right? So, you know, that’s kind of the three big levers they’re pulling as competitive advantage. And so you ask yourself, fine. How is this gonna play out over time? Well, it’s gonna keep making them stronger. The more they flood into logistics, robotics, fulfillment centers, smart drones, computer vision, all of that, and the more they flood into Amazon Web Services, AI capabilities, cloud, and all the merchants move their stuff. I mean, they’re getting massive economies of scale in both of those, and the more they spend, the stronger they get. And it should just increase and increase and increase, assuming they’re well managed and the money is well spent. So that’s a massive sort of strategic move. And okay, what about their purchasing economies? Well, the bigger they become as a retailer, in theory they should be able to spend, get better deals than most of their rivals, maybe not Walmart, but 99. percent of all the retailers don’t have their purchasing power when dealing with suppliers. So they’re getting stronger there as well. And then you ask, okay, what about the network effect? The network effect is getting bigger and bigger. I mean, they’re they went from hundreds of thousands of merchants available to millions to tens of millions from one country to two countries to five countries to 19 countries. I mean, these things won’t go on forever, but they don’t look like they’re flatlining right now. So the things that make them powerful appear to be increasing. Now that would be sort of level two thinking competitive advantage. We move down to level three, which is barriers to entry and soft advantages. I’ll put the slide in, you can see how I’ve broken that down. What jumps out at you as, I mean, a barrier to entry is, a competitive advantage is your strength against a rival, someone who’s in your business. They could be a large rival like Walmart, or they could be a small rival like your typical retailer. So that’s how we think about competitive advantages. But barriers to entry, we think about new entrants. Does this prevent someone from jumping into my business? So we look at the cost, timing, and difficulty of entry. How difficult would it be to replicate what Amazon has built? And we can look at its platform business model, the chicken and the egg problem. getting millions of merchants on their platform, and we can look at their fulfillment in infrastructure capabilities, all those warehouses, all the robotics, all the AI, Amazon Web, it is, I mean, how could you jump into that business? I mean, it would take so much money, and so much time, and so much investment to replicate what they have built just to get into the business. And then once you’re in the business, then you’ve got to deal with their competitive advantages that they can still outspend you on IT and fulfillment every year. So they’ve got a massive barrier to entry. They’ve got massive competitive advantages. So, you know, across the board, all of that looks very impressive. So the questions I asked, and I sent this out in a note to the subscribers, you ask your question, okay, how is this going to play out? over time, because we’re in the strategy business, so we’re trying to see a year or two years down the road, not the next month, how is this strength gonna play out versus rivals, new entrants, and substitutes? And I always ask this question. Okay, how does it play out against large rivals? Walmart, Carrefour, Target, Best Buy. Could a large rival take market share over the next two to three years? That would be the competitive picture. I don’t see how Walmart, I think Walmart’s a serious competitor. I think Target is a smaller but serious competitor. If it’s not one of those giants, I don’t see how any smaller rival could compete with them in the vast majority of goods that they offer. Now you could do a niche play. And I’ve written about specialty e-commerce, how you can win there, let’s say in groceries or certain types of apparel. There are niche strategies, Etsy is very interesting, but in the core business that they do, which is general merchandise, basic goods and services, things like, I don’t see how you can beat them. I don’t see how you can take market share. Unless there’s a technological change or their management just starts doing dumb stuff. The structural advantages they have are too strong. Okay, that’s rivals. What about new entrants? Who could jump into their US business and take 10%? of their e-commerce business. Again, you have to start looking at specialty plays like TikTok jumping into e-commerce or Facebook plus Shopify So I’m keeping an eye on so the answers to those questions right now are I don’t see it I’m Watching very closely, but so far. I don’t see a large rival or a small rival That’s a threat if and what I like about their business is if there is a threat. I think I’ll see it coming a long way off it will take years and years to build all those warehouses. So it’s not gonna be a surprise. Right now, I don’t see any major threats. Last one, what about substitutes? I hate low cost substitutes. I hate any business where you’re competing against something that’s free and you’re trying to charge. Or that there’s just a substitute. What is the substitute for most of the stuff you buy on Amazon e-commerce? I don’t know, headphones. a sofa, a chair, detergent, you know. Most of those physical products that they sell, I mean, they have alternative goods you can buy, but there’s no substitute for any of those that Walmart, I mean, that Amazon doesn’t also sell. There are substitutes for some of the products, but there is no substitute for the service of Amazon e-commerce. that’s cheaper. I mean, you could go to the Walmart, you could walk down to the convenience store, you could walk to the grocery store. So there’s alternative retail platforms, but I don’t see one that’s cheaper because of the economics of fidget physical goods. I don’t see any way anyone can come in with a lower cost substitute than Walmart, Costco and Amazon. They’re as cheap as you get. So I like that. So I mean, generally speaking, here’s, I’ll finish up on Amazon. I like all of this. I think the competitive advantage picture is daunting and getting stronger. I think the barriers to entry, level three, is really daunting and getting bigger. And I don’t see how serious rivals, I mean, serious rivals I could watch. I don’t see small rivals as a threat and I don’t see any low cost substitutes that worry me. So the only thing that could really maybe surprise me here is if there’s a technological change. And sometimes when the tech paradigm changes, that gives someone the opportunity to jump in and change the game, which is really what Amazon did. Walmart and Sam’s Club and Costco were the dominant unbeatable business model and it took a tech change. for a company like Amazon to jump in and do an online version. So absent a tech paradigm shift, I’m not sure. I’m watching very closely, but so far, this looks like an incredibly strong hand that’s getting stronger. That’s where I am on this one. Okay, now the reason I wanted to tee that up that way, and I wrote about this the other day, is because when you ask those same exact questions to Amazon Video and Netflix, you get completely different answer by asking the exact same questions. So what about Amazon Video? I mean it’s basically the Netflix model. You know they create content in-house which is TV shows and movies and they purchase and license other TVs and movies mostly from Hollywood Studios if you’re in the US but if you are you know it’s actually fairly localized. you know, 80 plus percent of the content that is created, whether it’s videos, TVs, things like that. I mean, 75, 80% of that is usually local. Actually, the head of Disney for China told me that. I was hanging out in his office in Shanghai a couple years ago, and he showed me this study, and he said, you know, most entertainment is local. There is very little crossing of borders. So, Hollywood is very famous for making movies Avengers and whatever That tends to cross borders But even when you look at say videos TV shows watched in Thailand or India or Germany You know 70 80 percent of most content types is local. So they’re doing a lot of licensing locally in all of their markets and they’re doing local production as well now there’s actually an exception to that which is Animated movies cross borders much more than the other types. So movies like Frozen, when you look at animation, I think the number was like 60% of animation is local and like 30 to 40% is cross border. But for everything else, it’s pretty local. Okay, so, you know, what is Netflix? What is Amazon? The first thing is it’s not a platform business model. This is a traditional linear business model. We buy content and we make content and then we bundle it all together and we stream it over the top for anyone with an internet connection. And what is their big pitch? Their big pitch is you can watch it anywhere you want. You can watch it on your phone, your iPad, your TV. They make it ubiquitously available. I think ubiquitously is, I’m not sure that’s an adverb there. And they make it very cheap. You know, that’s its convenience plus low price. Now, whenever you hear of a business model that is convenient and low price, that is the hallmark of a digital disruptive business model. Like it’s just the go-to strategy for startups in Silicon Valley is, let’s take an existing business model like the cable bundle. You know, the average cable package, let’s say in the US is $105 per month. Let’s take a traditional business model. and use new digital tools to create a new digital business model that makes it more convenient and cheaper and ideally makes it free. That is the go to disruption strategy. So that’s YouTube, right? Everything you could ever want to watch and it’s free. That’s WhatsApp. It’s your SMS package, but it’s free. They’re always targeting new existing behaviors. What they don’t like to do is create new behaviors because new behaviors take a long time to emerge. We want to look for an existing behavior and just make it cheaper and cheap and easier to use. Get rid of the friction, make it convenient, make it cheap. That’s standard. So whenever you see that business model, the first two things should jump out at you. Number one, that is usually an attack on a barrier to entry. If we had looked at Blockbuster Video in 1998, when we had talked about its competitive strengths and its barriers to entry and we’d run the six levels, one of the barriers to entry would have been, oh, they have a whole lot of stores everywhere in the US, so if you wanna compete with them and jump into that business, you would have to open 2,000 stores. That’s a barrier to entry. And in the world of physical rentals, it was, but digital changed it. And once you started streaming, or they actually started by mailing DVDs before streaming them, it basically used digital tools to wipe out the barrier to entry. And we see this all the time. If you wanted to do a startup 10 years ago, the first $2 million you had to spend was on buying servers. So all the venture capitalists would give a couple million dollars and you would buy a couple bunch of servers and you would create your mobile app. Amazon Web Services wiped out that barrier because now you can just access server capacity as needed without having to buy any servers. You didn’t need two million dollars. You could just immediately use it as needed by AWS. We see that play all the time. Let’s disrupt record stores. That’s iTunes. Let’s disrupt video rental stores. Let’s disrupt bookstores. So whenever we see that, usually that’s an indication we’re using digital tools to wipe out a barrier to entry. Okay, fine. So let me sort of run the same list I just did for Amazon. We look at the competitive advantage list. Do they have a share of the consumer mind, some sort of habitual habit formation? addictive, aspirational, emotional. Now certain types of content do very well in this competitive advantage. Like certain people love the Avengers or love, I don’t know, werewolf movies or whatever and they’re just super fans. And anything Star Wars makes the fans would line up for weeks ahead of time. Well until Disney took it over and Kathleen Kennedy destroyed the franchise. But… It used to have tremendous power on the demand side with a loyal fan base. There’s a lot of ways to get there. Amazon Prime and Netflix don’t really have that. It’s a good service. People don’t love Amazon Prime, Amazon, I’m sorry, Amazon Video the same way. They don’t love their cable provider. Now they may love certain content. So there’s some power there, but generally the service is just a service. Do they have switching costs? No. In fact, Amazon and Netflix make it super easy to cancel your package anytime you want. Because they say that’s more convenient. I cancel my Netflix package all the time. I turn it off, I turn it on. It’s super easy. They don’t want an inconvenience. Switching costs are a type of inconvenience, but Netflix and Amazon Video are based on super convenience. It’s very hard to build switching costs on the consumer side. Even Amazon e-commerce doesn’t do this. Now they do build switching costs on the merchant side, but these businesses in video are not platforms. There’s only one user group, which is the consumer. So no switching costs, no searching costs, limited sellers long-term, nope. Okay, we move down the list. CA5, network effects. There’s no network effect for these businesses. This is a linear, this is like a cable package. and it’s like a movie studio. It’s not a platform business model doing content for entertainment like YouTube or TikTok or Instagram or Spotify. This is a linear business model. They don’t have network effects. So I just went down half of the competitive advantages and they didn’t have much. We moved down the other half of the list, the supply side competitive advantages. proprietary technology, learning effect, scarce resource, location, nope, nope, nope, nope. They have some advantages here, it’s not nothing, but nothing knocks you over. And what you come down to is the competitive advantages people always talk about for Netflix, which are purchasing economies and fixed costs economies of scale, which I sort of started with. Okay, so what about their purchasing economies? I just said that when Amazon e-commerce acts like a linear business model, a retailer, they have purchasing economies just like Walmart because they buy from hundreds of thousands, millions of suppliers, and they’re a big buyer, and they get a good rate, and not just a good rate, but they get good terms of service. So their payment terms are quite good. That’s why you see negative working capital. Because they can say, you know, I’ll pay you in 90 days and the sellers have to say, okay Now you could say that Netflix and Amazon video have that as well because they can go to content creators Movie studios Warner Brothers Marvel But they can’t bully them that much Content creators who have popular content have they have negotiating power You can’t just go to Marvel and say, here’s my terms, take it or leave it, because Marvel will say, forget it. Because they know that they’re popular. So they don’t have that much power here. They have some, but they can’t bully their sellers the same way that Amazon e-commerce can just basically tell the people who make, I don’t know, remote controls, here’s my price, take it or leave it. A lot of these people, the people who make. Game of Thrones, HBO, they’ll say, forget it. This is one of the reasons Spotify does not have great gross margins because they need popular music and five to 10, I don’t know how many, like five companies own most of the popular music and they can’t bully them. So yes, they have purchasing economies and this is sort of gets me back to what I started with. When you look at these various concepts, you gotta take it to the next level because you realize purchasing economies in e-commerce are much stronger than purchasing economies and entertainment. if you’re buying from the movie studios. Now, if you are a platform business model like YouTube, you have tremendous power here as a platform because the users create all the content for free and they don’t pay them really anything. But for this case, no, I don’t think Netflix, I think they have some power. I don’t think it’s that nearly as strong as in the e-commerce business. So that brings us to the same point, which is economies of scale. for fixed costs in these over the top streaming bundles, Netflix, Amazon Video. This is the power that everyone always points to, Hamilton, Helmer, Seven Powers, they always point to this. I don’t think it’s that true, I don’t. I think when Amazon e-commerce decides to spend $30 billion per year, which is what they’re doing. on things like warehouses and robotics and fulfillment and tech, I think that is tremendously powerful. I think when you flood $10 billion in content, it doesn’t, they’re not in the content volume game. They’re in the quality content game. And creating quality content at scale is not about spending money beyond a certain point. And I think that’s really what’s been happening with Netflix. They are spending tons of money on content that sucks. I have a Netflix package. I signed up when I was in Bogota. I pay $4.50 per month. It’s ridiculous. I’m not convinced it’s worth it because when I go on Netflix and I look for good stuff, the vast majority of stuff sucks. I mean, it’s really this idea that you’re just gonna throw money at content because it’s your major fixed costs and you’re going to get quality is not true. It has a lot to do with talent and it has a lot to do with the fact that there probably isn’t that much quality content every year anyways. You probably can’t create thousands of great shows just by spending money. There’s probably a limited amount of talent in the world. So it taps out. So I don’t think they’re, they’re strong there, but I think when you look at their falling share price, The biggest complaint they have is they are a well run tech business with a very good tech strategy, but that is secondary. Their primary skill as management of Netflix and Amazon Prime is quality, and they seem to have a problem with creating quality content, regardless of the business model you build around that. The business model, the tech strategy is the car, but the engine is creating quality content. and they seem to have a problem there. That’s kind of how I break that down. And I wouldn’t say that about e-commerce. I think e-commerce, the strategy in the business model is 80% of what’s going on. I think for an over-the-top streaming business model, that’s 50% of what’s going on. Anyway, so we go down the list and I don’t think they’re competitive advantages. I think there’s a problem there when you break that one down. Okay, I’ll finish up here in a minute. Okay, let’s go down the list a little bit more. You go to, oh, here’s a number. Amazon spent 11 billion on Amazon Prime Video and music content in 2020, which was a 41% increase from 2019. So that wasn’t Netflix, I’m sorry, that was Amazon Prime, Amazon Video. So you can see they have really hit the gas pedal on spending on content in the last couple of years, and it doesn’t appear to be paying off. Now they’ve also hit the gas pedal on their spending on warehouses and that appears to be working. Okay, we move to level three, barriers to entry and soft advantages. Okay, they’re not a platform business model. So they don’t have chicken in the egg. They don’t have tons of user generated content. They don’t have any of that. What they do have, they do have a barrier to entry and the barrier to entry is their library of content. If you want to compete as a new entrant into the streaming game, you have to have hundreds, if not thousands of shows from day one to play this game. Netflix has that, Amazon Video has that, Disney looks like they probably have it, HBO Max maybe will get there. You do have to acquire a certain amount of content, so you can’t just sort of step in with five TV shows. So there is a bit of a barrier there. It doesn’t look overwhelming. It looks moderate at best. But that is probably protecting them to some degree. But if you have a hit TV show, people will jump in, they’ll sign up, they’ll watch, you know, WandaVision. And then as soon as that series is over, they’ll cancel their subscription and go somewhere else. We see that a lot. Okay. So, here’s what I think people are getting wrong. I’ve explained to you why I think Amazon e-commerce is stronger than people think and I think it’s getting stronger. I think Amazon video and Netflix are weaker than everyone thinks because when I look at the digital operating basics, we’ll jump to level five. That’s what most of what these companies have been doing. I mean, here’s the digital operating basics. I’ll put the slide in the show notes. DOB1, rapid growth at small incremental cost. That’s Amazon going. Amazon video going global like Netflix, hundreds of countries very quickly. DOB2 never ending personalization. That’s what Netflix is famous for. They tailor the content to each individual user. DOB3 digital core for management and operations. That’s what these businesses are. They’re digital operating business models that are a contrast to the traditional cable operating business model. DOB5 leadership management, DOB6, 7, cash engine. When you look at what Amazon does and what people, Amazon video and what people say are the strength of that model, most of what people are talking about is the digital operating basics. Not competitive advantages, not barriers to entry. I think that’s most of the Netflix story is the fact that they went digital with their new digital business model and they did the operating basics very well. and they got there before everybody else, and it was a strong contrast to the cable operating model, which was $100 a month. I think that’s what’s been going on. And now what’s been going on in the last year is we are seeing more and more rivals jumping into this business, doing the digital operating basics well, HBO Max, Disney+, Peacock, all of these. And it turns out a lot of companies can do that stuff. And when you look at Amazon Video and Netflix against other similar business models, not cable business models, but similar business models, they don’t appear to have many strengths. So I think that’s kind of where they are. We’re seeing the fact that, okay, everyone’s doing the digital operating basics now. You got there first, good for you. That was very powerful against the incumbent, but now there’s a lot of companies doing the same business model. And it doesn’t appear that you have that many competitive advantages really. Your competitive advantages, if anything, are getting weaker and they don’t look very formidable. So I think this was a short-term phenomenon. That’s my working diagnosis here. This was a short-term phenomenon about a digital transition from cable to over-the-top streaming. And now that the transition is pretty much over, we’re seeing who is strong and who is not. And most of these companies don’t have that many strengths. So I think we’re gonna see a lot of competition. I think they’re gonna have to spend more and more on content. I think they’re gonna have to spend more and more on marketing just to stay in this game. I think the unit economics are not gonna be as attractive. I think the growth rates are gonna slow. It’s gonna look like a digital streaming business without any massive advantages. And one last point, and then I’ll finish here. I do not like the digital content business, unless generally speaking, I don’t like the digital content business. I don’t care if you bundle it. I don’t care if you stream it, I don’t care if you put a thousand shows. If there aren’t network effects, I really get scared of purely content businesses. Now I like software businesses like Adobe, but pure content businesses, we make TV shows, we make movies, yes we’re bundling them. It’s a really difficult business. The only content businesses I really like are when it’s a platform. with network effects based on user generated content, which is TikTok, YouTube, Instagram. Then I think you’ve got some real power, but outside of that, it’s just, the competition is just brutal because anyone can create content these days. Anyone can create it, anyone can distribute it. There’s just, it’s like the book business. Like I’m in the book business. I write books and I sell them. And these are digital content. It’s a terrible business if you’re going for any sort of scale. Now, if you’re a small niche player and you’re selling consulting and investment and others, then it’s a nice compliment to that. But as a standalone business, generally speaking, content is terrible. Content plus services is pretty good. Content with network effects can be good, but standalone content as a service, content as a product, hard to find a good business. There’s a couple, but it’s pretty rare. Anyways, that’s kinda how I see it. Okay, I’m going to write this all up very sort of systematically and I’ll send it out to subscribers in the next day because there’s some tactical stuff here that Netflix did well as well. But those are the two main ideas for today. Economies of scale based on fixed cost, you have to take it to the next level because it really does play out differently. And then digital operating basics, you really got to keep an eye on that because a lot of times when people are talking about competitive advantages, They’re talking about the digital operating basics by someone who just got there first. And others are gonna copy that, and that’s just the way these businesses operate, and a lot of the strength that you seem to have is gonna go away. And that’s why I break these things down into six levels and sort of go through it in such detail, because when you do it systematically that way, you really see like, oh, I’m kind of misjudging that. Like, hey, I thought that was a real strength of Netflix. That was just kind of the operating basics. And for those of you who’ve read my books, one of the slides I keep saying is, look, there’s six levels, but most of the long-term strength comes from the top four. And digital operating basics is number five. So that’s why I even, I put a graphic and I circled the top four. I say, that’s where you wanna look for long-term strength. And when you look at Netflix and Amazon video that way, you realize most of what people are talking about is not in those top four. In fact, there’s not that much going on there. In contrast, Amazon e-commerce, the top four levels, are really impressive and appear to be getting stronger. Okay, that’s pretty much it. As for me, it’s just been a nice quiet week. I like that I’m sort of at home for a little bit and I’ll go out back on the road. Couple weeks Singapore and then probably a little bit in Thailand and then looks like I’m going sort of Eastern Europe and Italy and that for most of the summer. So it’s kind of nice to have some downtime, just relaxing and spending a decent amount of time sitting on the sofa and just vegging out, which is, I never used to do that before, so that’s kind of new. What else? Oh, Doctor Strange, I went and saw that. Pretty solid for those of you who are sort of Marvel, I mean, I’m obviously a Marvel guy, I mention it all the time. It was solid, it didn’t knock me over, but it’s not bad entertainment and kind of fun just to sit and watch that, so. Yeah, I mean, I’d recommend seeing that if you’re kind of like the Marvels and Avengers and all that stuff. Yeah, that’s pretty good. Anyways, OK, that’s it. I’m going to go ride the scooter. And you always have to wait till the end of the day here when the sun starts to go down because it’s too hot during the day. So the sun’s it’s about 5 p.m. now. So it’s a good time to take a scooter ride. Anyways, that is it for me. I hope everyone is doing well. And I’ll talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.