This week’s podcast is about GE and their big digital transformation initiative from 2011-2018. However, I am not a GE expert by any stretch. I am just presenting a very simplified version of their digital initiatives (from case studies) for a discussion about digital transformation.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here’s my playbook for the digital transformation of an incumbent.

——–

Related articles:

- Why I Really Like Amazon’s Strategy, Despite the Crap Consumer Experience (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Big Questions for GoTo (Gojek + Tokopedia) Going Forward (2 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Digital Transformation

- Industrial Internet / IIoT

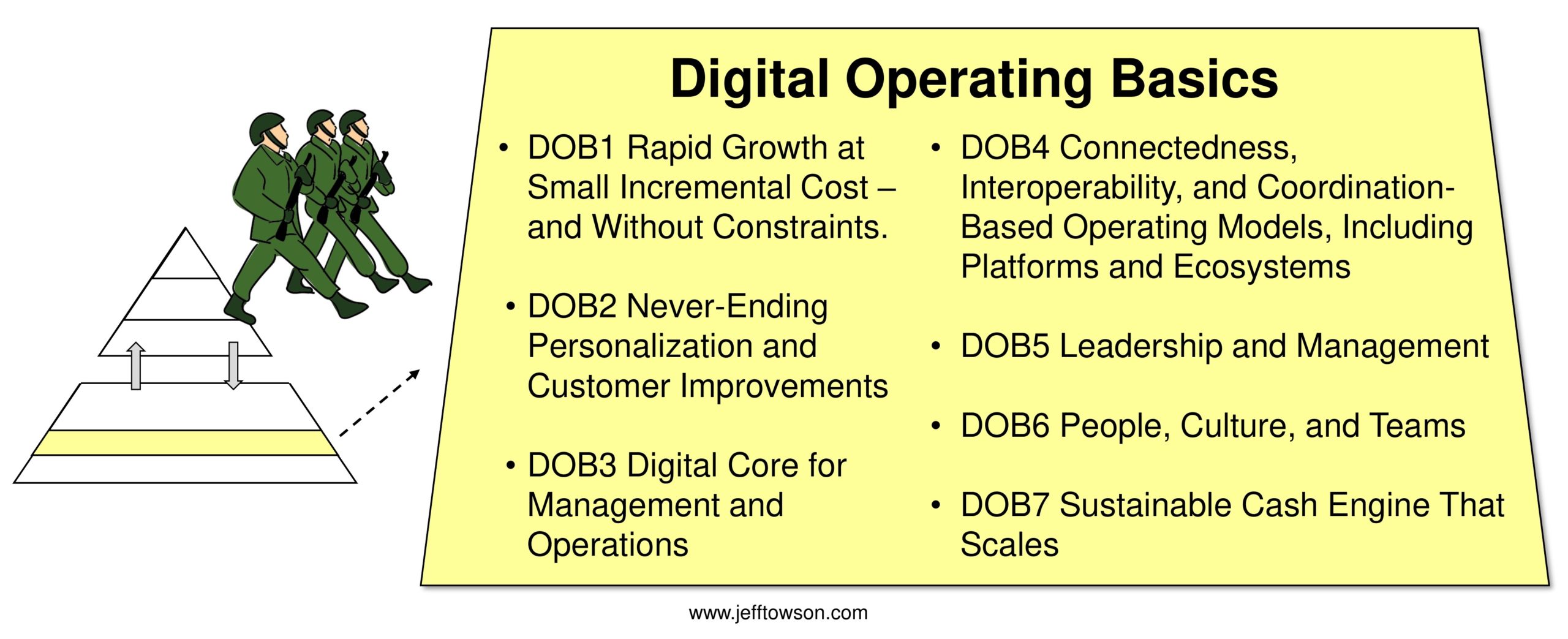

- Digital Operating Basics

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- GE

Photo by Kind and Curious on Unsplash

——-Transcript Below

:

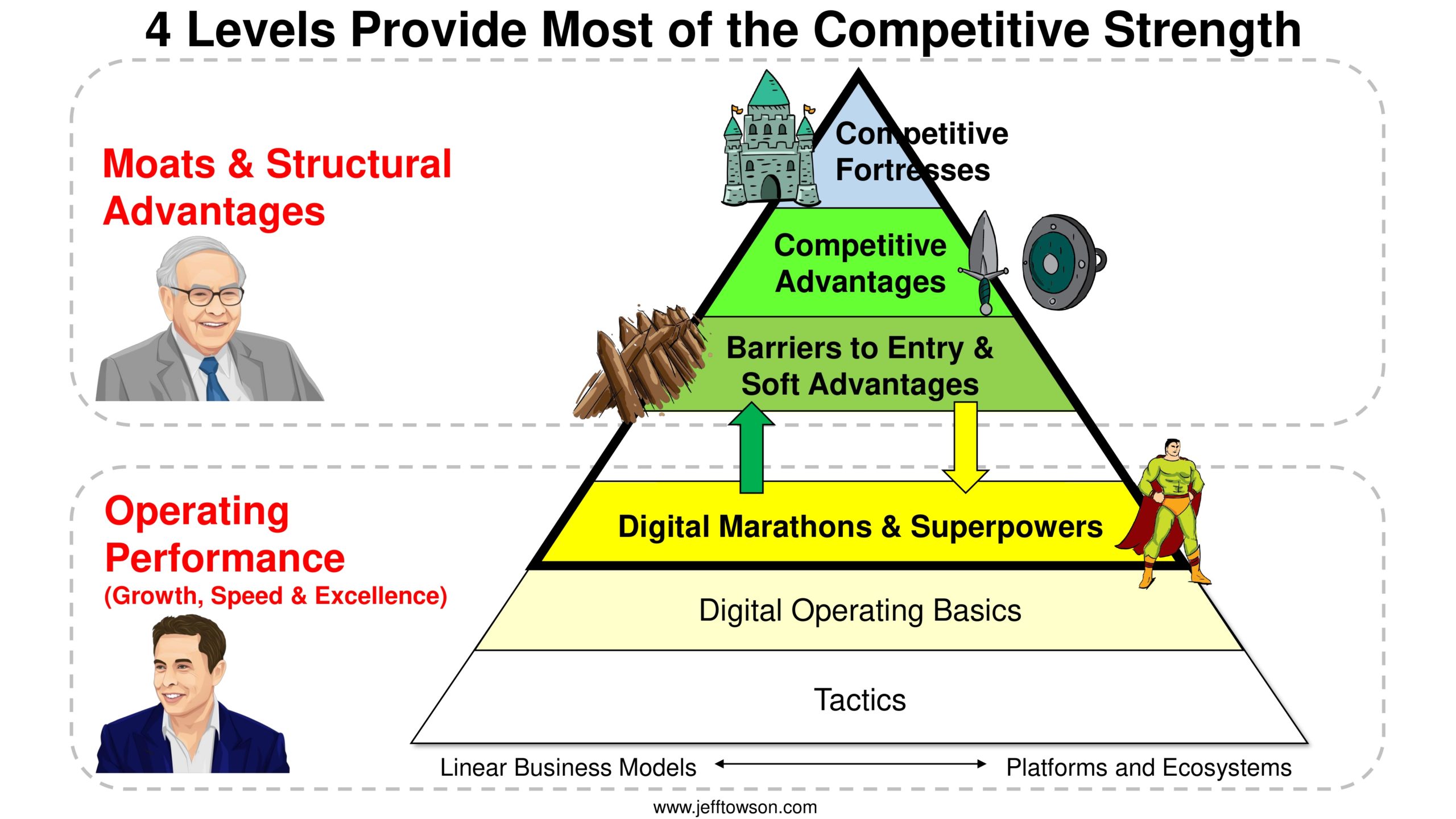

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast. And the topic for today, why GE Digital failed. So far. And it’s a pretty important case. I was actually going through this with a bunch of MBA students this week. It’s a fairly well-known case. And I thought there were some really great lessons. I mean, because this is like GE. This is massive, tech-focused, industrial conglomerate. that went all in, I mean this was a 10 year effort with full support from the very top of the organization to Go Digital, which in their case really we’re talking about Industrial Internet of Things, Industrial IoT, and really in the last year or so they’ve kind of walked away from it. I mean failure’s a bit of a strong word, but I mean thus far the first phase of this major initiative. didn’t work like they thought. Now what they’re gonna do next, we’ll see, but it looks like they’re kind of walking away from it significantly in the last couple years. So there’s a lot of good lessons in that, and I thought that’d be a great case in sort of digital transformation, digital operating basics, moats for digital, things like that. So that’ll be the topic for today. Basic stuff, for those of you who are subscribers, I did send you out in the past day. sort of the beginning of a deep dive on Alipay Plus, which I think is gonna end up being a big thing. And I think I’m pretty much the only person writing about it at this point. This is Ant Financial, major IPO, major financial services company. The IPO got pulled at the last minute. They kind of went pretty quiet for the last year or two. And a big part of what Ant was doing was Glowing International, under Alipay as the first wave. Well, in the past six months, they’ve rolled out something they call Alipay Plus, which I think is gonna be the foundation of their new international push, starting in Southeast Asia. Anyways, I sent you part one yesterday, I’ll send you part two in the next couple days, and I’ll probably write more about this. I think it’s a pretty big deal. So that’s something to keep an eye on, and if Ant ends up filing for IPO again, which there’s been rumors of in the last couple days, that’ll be kinda interesting. So anyways, that’s what’s next. For those of you who aren’t subscribers, feel free to go over to jeffthousen.com. You can sign up there, free 30 day trial, see what you think. Other housekeeping stuff, the books are on sale, motes and marathons, eBooks and paperbacks, except for number three are on Amazon. The paperback for number three, part three, is on Barnes and Noble. There’s a bit of a glitchy thing going on there. Anyways, that’s available there. And let’s see, standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guests may be incorrect. Views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Now, as always, there’s a standard sort of concepts to keep in mind. And really, I guess today we’ll just go under digital transformation, which is… You know, fairly sweeping topic. This is what companies are doing. I’m doing consulting in this. I’ve really been launching in this in the last six months, doing a lot more of it. So yeah, this is pretty common. A lot of retailers, banks are dealing with digital transformation. And you know, industrial, the more operational you go, the more physical you go, digital transformation becomes a lot more difficult. you know, it becomes a lot more about, hey, let’s just run analytics on all the data we already have in our bank servers. That’s very digital. Or media would be the same way. Let’s take all our videos and stream them. You are still mostly working in intangibles, software, digital. As you move into the physical world, let’s ship packages, gets a little more complicated. Well, as you go into industrial, then it is actually a lot of tangible stuff going on. you’re starting to digitize factories, machines, things like that. So one, it becomes a lot slower. It’s a much bigger endeavor. And two, it also becomes much more complicated. When you think about digital creatures, most of them are fairly simple at their core. We are sending money. We are sending a package. I mean, they are operationally very standardized along the… couple services. Well, when you start looking at sort of an old school industrial company, operationally they’re very complicated and you’re talking about hundreds of different products and services. So it’s a much more complicated thing. So within that spectrum when you start talking about digital transformation, an industrial conglomerate like GE is about as complicated as you can get. So that’s why it’s kind of a good case. Now when we talk about digital transformation, and that’ll be the concept for today, which will go into the concept library, I really break this into three levels, which you should be familiar with if you’ve listened to this podcast. I talk about moats, competitive advantages, right? Warren Buffett land. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, read the books, four bucks, five bucks, whatever it is, digital operating basics, and then tactics. Right, those are kind of of my six levels of competition, three of them, motes, digital operating basics and tactics. When we start talking about digital transformation of a company, supermarket, media company, industrial company, 75% of what we’re talking about is doing the digital operating basics. And I’ll talk more about this for GE. 20 plus percent of what we’re talking about is building a mote, and then the other five to 10% are about tactics. That really for me is what it means to say digital transformation, and I’ll put a slide in the show notes that basically say, look, that’s how I break it down. So if you’re looking for a playbook for digital transformation, that’s my playbook. 70, 75% do the digital operating basics, 20% think about strategy and modes, 5% to 10% think about tactics. And I’ll talk about what those mean specifically for GE. Now, for the GE case, this is really from a Harvard business case. So I can’t post it, obviously, because it’s, you know, you have to pay for them and they’re very sticky about their IP and stuff. So I’m just going to talk about main points about GE’s transformation effort. But a lot of, I mean, most of this information is coming from a Harvard business case called Digital Transformation at GE, What Went Wrong. Actually, it’s Ivy, but it was, you can find it under Harvard. So. a lot of the facts you can find, or you can find it online. This is not exactly scarce information. But I mean, basically 2018, 2019, you start hearing about various board level, CEO level changes at GE, new chief operating officer, Larence Culp, gets installed as a… basically new CEO of GE 2018, replacing John Flannery. John Flannery had only been in that position for about a year. And then prior to that, I mean, really we’re talking about Jeff Immelt, for those of you who know the history. Jeff Immelt was the CE and it’s sort of guiding leader for, I’m gonna say 14 years, I’ll check that. But I mean, he was really the leading person at GE for a long time. I actually met him, must’ve been 15 years ago. I was working for Al Waleed, Saudi Prince Al Waleed in Saudi Arabia, in Riyadh, and he would always meet with famous people. It was very normal to walk out of my office. This was a kingdom center at the center of Riyadh, the big skyscraper that looks like a ladies’ razor. Although Al Waleed apparently doesn’t like that analogy. In the hallway, I don’t know, there’s Prime Minister Tony Blair. Which is true story, like I literally opened my door one day, came rushing out. He was right there in my doorway. I almost hit him with my coffee. Like it was, it was one of those moments where you open the door and I’m rushing out and like time slows down and it’s like, Oh my God, that’s Tony Blair. One 18 inches in front of me. Oh my God. I’m going to hit him with my coffee. And you, it’s like slows down. You’re like, Oh my God. And then. for some reason like the coffee just didn’t fly out of my hand but it was real close and it would have hit him square in the chest uh… but that was kind of a norm not well that day was a little bit unusual but not an abnormal occurrence president of the philippines jeff in melt uh… who’s that big lots of press coming in all the time cnn and bbc and who’s the big maria Betrlova, who’s over the big financial reporters. I mean, it was just a common thing. So anyways, one random day, you get the phone call, oh, we’re meeting with GE and their people in the boardroom because Al Waleed met Jeff Immelt the night before, which would be a common thing. We wanna talk about doing stuff together. So I come in and I’m sort of one to two seats to the right. I’m not the point guy. I’m sort of assistant to the point guy. And there’s Jeff Immelt and he’s got his whole team behind him. And we actually started working on ideas to work with GE in Saudi Arabia. We ended up hiring McKinsey and doing work on power plants, water, energy, consumer credit. It was kind of a big thing. It never really went anywhere. Kingdom really wanted to do consumer credit stuff. GE really wanted to do power and water, which is not something Kingdom did. But anyways, it was fun. Anyways, he was an interesting guy, fun to talk with. A bit of a difficult company to work with because you would meet them in Saudi Arabia, would fly into London to meet them at the GE office. And literally almost every meeting it was new people. It was like new vice presidents because there’s so many executives and they move around so much that every meeting it was like handing out business cards again. It’s like, where’s Bob? Oh, Bob’s now doing GE Capital. Oh, where’s Susan? Oh, she’s transferred. And it was like every meeting it was like people were new. It was a little frustrating. Anyways, random story. But okay, so we look at GE, for those of you who aren’t familiar, GE is Thomas Edison’s company, light bulb, invents the light bulb, builds the first industrial really research lab that’s sort of paired with manufacturing capacity. So then they start the process, which GE has done ever since. And so as Huawei, which is like, we have a ton of R&D and we have a ton of manufacturing. Let’s stay on the frontier, lots of R&D, and we will focus on industrial products. We will focus on high-tech products, and we will focus on products that are growth. And that’s where these, I mean, Huawei’s more focused on telco. GE is more of a portfolio approach where it’s gotta be industrial, high-tech, and growth, and then they’re always sort of fine-tuning their portfolio, and they do things like power plants, and turbines, and clean energy, and lots and lots of M&A. So. Anyways, but their business model has always been we sell products, manufacturing-based products, and then we sell supporting services, maintenance contracts, service contracts, and that’s been their business model forever, and it’s a pretty good business model. And that wouldn’t really be relevant to what I talk about, I mean, sort of high-tech manufacturing, innovation-intensive products, industrial products with supporting services. Well, I mean, Jeff Immelt… one of his major initiatives, and he had several, but this was arguably, let’s say top five, was to begin to shift GE, their strategy, their competitive advantage, away from making and selling hardware, which is increasingly becoming commoditized, and towards what we would call smart and connected products. And we see this pattern all over the place. I mean, it’s… You know, it’s LG making refrigerators, and now they’re making smart and connected refrigerators. It’s Steve Jobs taking a phone, a mobile phone, which is sort of a dumb device, and making it smart and connected, hence smartphone. And we see this all over the place. You put a little smart and connection in a bicycle, and you get bike sharing. And we see this all over the place, and some of it is… fairly minimal. Let’s make a smart and connected toaster. Who cares? But home products are more smart and connected air conditioners. That’s better. Smart and connected cars. That’s Tesla’s world. But definitely within that whole process of let’s take hardware and make it more digital. Industrial, particularly high-tech industrial, is a fairly compelling space. And so, Imolt starts doing digital and he starts saying, you know, starts talking about things like industrial internet of things. And I mean, ultimately, he basically said, look, GE ultimately has to become a software company first, and then hardware second. Now, you know, I’ve given talks in the past about digital economics. And when you start talking digital economics, which is a fairly dry subject, also called information economics, You start talking about bundling. You start talking about digital cost structures. You start talking about pricing and versioning. And if you go into my concept library, and you’ll see all those things listed, look for digital economics. But one of the ones you start talking about is complements. In particular, digital complements. Your smartphone is effectively a piece of hardware, which if you bought it from Apple, you paid for the hardware. and then they gave you a bunch of digital compliments for free, which are all the apps. Hundreds of thousands, millions of them really. And Apple has always made the decision, we’re gonna charge people for the hardware and mostly give them the digital compliments for free. And other businesses have gone the other way, like Xiaomi, we’re gonna basically sell the piece of hardware, the phone, at cost, plus or minus two or three gross margin points. Now they’re increasing it. and we will try and make money on the software, the services, i.e. the digital complements. And one of the reasons this is such a powerful move is if you add a compliment to a product, it makes it more valuable. If I am selling hot dogs, hot dog buns are a compliment. They make the hot dog more valuable. Mustard is a compliment. It makes the hot dog more valuable. A better example would be electricity. If you pay for your electricity bill, there is a certain value to that because it turns the lights on. But when people started to make appliances 100 years ago, the appliances in your home, even though they’re separate products, are compliments to your electricity. That’s why your electricity bill is an unbelievable bargain. Because you’re paying for the electricity, but the value you get from that, from… the lights and all the other home appliances, which are complements, make your electricity dramatically more valuable. That’s kind of the nature of this game. And obviously you could see in industrial products, making turbines, making wind turbines, solar panels, clean energy, power plants, which GE does all this stuff. As you start to digitize, the complements are gonna change the value proposition and you wanna be in that. And then there’s always a fight. There’s always a fight of who is the complement to who? Is the mustard a complement to the hot dog, or is the hot dog a complement to the mustard? And what every party in this interaction wants to do, they wanna charge as much as possible for their product, and then they want all their complements to become cheap commodities. So the hot dog people want mustard in buns. to be very cheap commodities. But the hot dog and bun people want the hot dogs to be cheap. Everyone’s trying to commoditize the other party. And that’s what Jeff Immelt is talking about. We were worried that hardware, which is what they do, is going to become a complement, a commoditized complement to software. So they’re moving that direction. And sometimes that is the case and that’s generally it looks like the case for a lot of hardware. It’s becoming commoditized and cheap and the power is in the software, which is pretty much now. That’s that that is a baseline assumption that is mostly true. There are exceptions to that. Tesla is absolutely an exception. It turns out the hardware is so complicated. The batteries. the engine control systems, and it is so tightly integrated into the software, which controls the brakes, the engine, all that, that you’ve basically got one integrated product, and nobody is commoditizing anybody. But on smartphones, let’s say a typical Android phone, you could absolutely say that, look, it looks like a lot of smartphones are just commoditized hardware, and then you stick in the powers in Android. and the powers in Facebook and the powers in YouTube. It’s not in HTC making a standard handset for 100 bucks. I can buy a handset smartphone online on alibaba.com. I can buy one for $20. And then you plug in Android, although you have to use an older version of Android, like Android 8. So, Emo was mostly right. Okay, so that gets you 10 years ago, they’re talking about all this stuff. And people start talking about, look, we’ve got to think about this commoditization thing, but then there’s a, and so you can start to talk about what does it mean to have a smart connected turbine, a smart connected solar panel, which they make. That’s industrial internet of things, turbines, locomotives, jet engines. They all have embedded sensors that generate tons of data. That data is then fed into software that then controls them. and improves business performance, cost, all of that. Okay, that’s sort of one level of thinking about industrial internet of things. And there’s another level though, and this is what GE started to talk about, which is, okay, everything I just said was sort of like smart and connected hardware, which in practice means you’re selling hardware plus services plus software. That’s the typical business model. That is the IBM business model. We sell hardware. We sell software that’s associated and we sell services that’s together. And that’s more and more what Apple is selling now. They’re selling more internet services, software services than they used to. Okay, there’s another level here, which is let’s start talking about ecosystems. What happens when all these devices become connected to each other? Well, that’s a. ecosystem play that’s a platform business model play suddenly we’re not talking about uh… android versus suddenly we’re talking about microsoft operating system where they control everything and they control the connections uh… that’s jd in alibaba smart logistics where you’re going to control the connectivity between all the smart and connected devices as opposed to just the smart and connected devices and that’s what companies like google Alexa, Amazon, that’s what they’re trying to do. And if you go into a typical store and you say, I wanna buy smart appliances for my home, washing machine, lights, plugs, curtains that move on their own, every company that makes these things, let’s say like if you’re in Thailand, true money, they will try and sell their own software. But most people immediately start to ask, is this compatible with Alexa? is it compatible with Google, right? We can already see a couple companies that are starting to control the whole ecosystem. Okay, so basically out of GE comes this idea to not just create smart connected products, but to create a platform which they call Predix, Predix, Predix, P-R-E-D-I-X, that would go head to head. with Amazon, Google, IBM, Microsoft, SAP, and this would be the operating system for industry. All of these things would tie together, all the data would flow. The company that was more widely used as an operating system would have better data, would have more interoperability. That’s what they really wanted to do, and they thought, since we are already… One of the largest industrial companies in the world, we already have the machines, we already have the customer base, we’re halfway home. We’ve just got to become the connectivity and the platform for everything. And that’s a very common product to platform strategy. I’m literally talking with two companies right now who want to do the exact same thing. We’re a major, traditional, pipeline, linear business model with tons of products. and tons of customers, we want to become a platform, in addition to being a product. So it’s product plus platform. And that was the GE play. So, I mean, you can look all this stuff and see what GE did, but you’re basically, they got a lot of, I mean, this isn’t all their sort of analyst calls for the last 10 years, digital GE, digital GE. You know, we want to be the operating system. The phrase they would use is, we want to be the innovation platform. such that app developers start to build on our platform because we’re connected to everything and we have all the data. So we wanna be a platform for apps that control things in the industrial internet. Okay, well, you’ve heard me talk about this, five types of platform business models, marketplace, learning. I mean, this would be innovation platform. That subtype of this I’ve always talked about is an audience builder. If you don’t know what that is, go to the concept library, look up innovation platform, but that’s operating systems. This is where you’re creating something that other people create upon, whether it’s being an app store, whether it’s being Microsoft Windows, whether it’s being Android, iOS, GitHub, there’s a lot of types of innovation platforms. Okay, so they wanna do this and they’re starting with their own customers, but okay, then you’ve gotta overcome the chicken and the egg problem. You know, to get all the app developers, you have to have all the customers using this. But to get the customers, you have to have the app developers. Huawei is basically trying the same thing right now to build another smartphone operating system, Harmony OS. So whenever I talk to them, my standard question is how many app developers are writing for Harmony OS right now? And it actually looks like they’re doing pretty good. They might actually finally sort of break the Android monopoly. Anyways. That’s kind of the thing and you can see GE over the past, you know, eight, seven, eight years, up until about 2018, 19, really struggling to make this work. Because it turns out when you start to become, one, you’ve got to decide your business model, which I think they did decide, but then you immediately realize saying, we want to be a software company and being a software company is very different. You need to have almost a completely different organization with a completely different set of capabilities. All those salespeople aren’t going to help you as much. All your engineers who are great at designing turbines are not platform builders. They’re not software people at heart. This is why a lot of these car companies are struggling to compete with Tesla because they’re not software companies at their core. and they don’t have armies of software people. Well, Tesla kind of does, because they were founded as really a smart company to begin with. So you get into this situation where you’re struggling to build out the capabilities and the organization, and that is a fairly sweeping problem. And I mean, GE has just had sort of one difficulty after another in doing this. Their sales force, struggled because their sales force was all about selling products to B2B customers. Suddenly, now they’re trying to woo developers, which is something like Microsoft is very, very good at. But you kind of, it’s almost like you’re doing software developer kits more than you’re doing meetings with people buying lots of turbines. You got to get users because you’re building a platform. It’s all about users, engagement, and the resulting data. They had to retrain their sales Customers didn’t have a huge amount of enthusiasm because even though it sounded good from your side, this is gonna be the keys to getting us to be a platform. Well, from the customer side, if I’m buying turbines, why does a software service package, why does that make my world better? Is this a 10X product that is 10 times better than previously? You need a killer use case. You need… you need to get adoption from existing customers. It’s gotta be awesome. It can’t just be okay. Anyway, so long list of issues that go forward. Fast forward to the end about 2018, 2019. GE, who knows? I mean, we’ll see what they’re gonna do next. But this was the central component of the transformation of the company, GE Digital. And they basically stopped talking about it. And they said, we’re gonna sell it. And then they said, we’re gonna spin it off. And it just sort of, I think they ended up spinning it off. I mean, it just sort of got pushed to the side. And there’s a lot of reasons for this. And I think it’s a great case in how difficult this can truly be. And I’ll give you my explanation for what I think really happened. But let’s just sort of simplify the situation. dramatically. And let’s say, look, basically, what really happened here was they wanted to become a software and a data technology company launched in 2011, major commitment from the top of the organization capital reorganization, highest level of buy in from the CEO, their strategy, we need to shift from an increasingly commoditizing hardware to more smart and connected and higher modern products. We need to become more agile. We need to adopt a decentralized organizational structure, something you’d see at like Microsoft or Amazon. We need to go beyond that to a product strategy. I’m sorry, a platform strategy. Everything I just said, that wasn’t enough. We need wanna go further. We wanna build an industrial IOT and ecosystem. We wanna be a platform first. And within that platform, we would like to… sort of control the technological standards for information exchange. That’s basically a standardization network effect. We wanna be the connective glue that not just we use, but all industrial companies use and all consumers use. So I mean, that’s like three levels of strategy there. Going from products and services to smart and connected product services and software. Going to a decentralized agile organization, we’ll call that level one. Level two and beyond that, we want to go from product to platform. That’s another level of strategy. And then level three, we want to become the technological standard for the industrial ecosystem, which is basically a massive network effect like Microsoft Windows. And that’s winner take all, probably. So that’s three levels of strategy there. And then the areas they kind of focused on, manufacturing, supply chain, healthcare, retail, seem to me the major ones. Okay, based on that, I’ll sort of give you a diagnosis. I just sort of defined, okay, digital transformation. What is digital transformation? 75% it’s about doing the digital operating basics. I’ll put the slide with my digital operating basics, well, not just mine, many people’s, in the show notes. That’s 70%, 75%. 20% is having a winning strategy, building a moat. Digital transformation is difficult. And if you’re going to go through all of this, you might as well go for something where you can actually win. Now, I actually think they did that. They had a win. If they had pulled this off, it was a winning play, like in the sense that they would have dominated the market. 20%, 25% is strategy, and then 5% to 10% tactics. OK, so when we, and I’ll put the slides in the show notes for those. So the first thing we can look at here is, look, this was just tactics. That was. the first problem you hear. Okay, you’re doing a strategy, you’re trying to build a ecosystem, I mean forget that, you’re just trying to sell smart and connected products. Do your customers want them? I mean, if you’re gonna get people to buy something new, usually the rule is you gotta have a 10X product. You’ve gotta have a product or service that is 10 times better than what exists. Usually that’s about being cheaper. That’s when people talk, oh, it’s a 10X product. Usually it’s like it’s a lot better and it’s a lot cheaper or free. Okay, I mean, and tactics, which is the bottom level of my six levels, my joke is tactics are just do whatever works. Look, whatever it takes to get adoption, whatever it takes to get usage, whatever it takes to beat your competitors, just do it. That’s why the symbol for this, if you look at my little six levels, it’s a street brawl. It’s a bunch of people slugging each other in the face. You know, you’re in this fight in the street, someone’s punching you, kick them in the chin, whatever it takes, just back and forth, back and forth. That is tactics. And when they sort of launch, I mean, they didn’t have an awesome thing that just took off. Did they have a 10X product? Did they just get adoption? If you don’t get that, none of the strategy or digital operating basic stuff matters, because you’re dead anyways. Usually businesses sort of start at tactical levels. Do whatever works. And then when you get some traction of some kind, you begin to standardize that into your operating procedures. And let’s just do a lot more of that. That usually becomes your digital operating basics. So issue number one, they weren’t getting any traction. All the strategy doesn’t do you any good if you’re not getting traction. Then you sort of get to, OK, that was a problem. And then we start to look at the digital operating basics. and you can basically just run the list and kind of see where they were struggling. And you’ll notice the picture I put for the digital operating basics. For tactics, I put a street brawl. People just slugging each other randomly in the street. Digital operating basics, the little cartoon I used was soldiers marching in a line. This is where you take the things that do work. which you probably discovered in your tactics, and you standardize them and you regiment them. This is instead of having a gang fighting in the street, you actually have an army that is doing these things systematically, hence the picture of the soldiers. You know, the digital operating basics, digital operating, DOB 1, digital operating basics 1, rapid growth at small incremental cost. If you’re gonna do something in software, do it big, because that’s one of the things software can do is scale quickly, cheaply, and without constraint. DOB2, never-ending personalization and customer improvements, Digital Operating 3, Digital Core for Management and Ops, DOB5, connectedness and interoperability, DOB5 and 6, leadership and management, people, culture and teams, DOB7, sustainable cash engine. Now you can see from GE’s experience, this is mostly what they were doing and this is where, even though they talked in terms of strategy, if I was an analyst on these calls, I’d be asking them about, are you getting the digital operating basics in place and working? Apart from adoption tactics, are you building the basics? Forget your ecosystem thing for a while. Just tell me about the basics. DOB6, are you, is your people, is your culture becoming agile? Are you operating like Amazon? Yes or no? And now actually, if you look at their, what they were talking about, their leadership and management seems to have been all in. So they were doing all right there, but their people and culture was, that was a major transition from traditional industrial GE to becoming a software company. And in fact, it might not have been doable. A company this big and this complicated and this ingrained, you may not be able, I think there is a point at which the company is too big to transform culturally. They may be too big. So. DOB5 seems okay, DOB6, big red flags, DOB7, is there a cash engine because transformation takes a lot of cash? Well, they have their traditional business. So yeah, they’re actually pretty good on DOB5, DOB7. Really the problem they were having, DOB6, DOB3. DOB3 is we’ve got to change our core operations and management behavior into a digital format. That was a major issue and I think again, a company the size of GE may be too difficult to do that in that you needed to just take one business unit and do that only. And then DOB4 is about connectedness and interoperability. That’s when you start becoming connected to other players in the market, your customers, your supply chain. They talked a lot about that. That tends to come later. It tends, when you start to digitally transform, it’s usually DOB3, 5, and 6. You build the core, you get your management and your teams, and you’re all digital. And then when that’s done, you then start connecting. more extensively with other players. So my first diagnosis of what was going on was the tactics, they just didn’t get the traction. The second was the organizational and capabilities issue, changing the nature of the company to a software company. They really struggled there. And it might be just too difficult for a company this big and complicated. As I said at the starting of this podcast, most digital companies are actually quite simple operationally. Their software is complicated, but you know, Lazada and Alibaba are just doing basic buy sell transactions. That’s all they’re really doing. Uh, Tik Tok as dynamic as it is, is still just doing simple videos. The products and services and core ops are quite simple. GE is the exact opposite of that. It’s incredibly complicated to sell turbines that work with Boeing. and Airbus and have maintenance for 20 years and our engineering, you know, frontier level engineering and, you know, so I think that was a problem. Tactics were a problem. The digital operating basics is probably where this thing came off the rails. Third level, last point, strategy. So we move up to the next level. We started tactics, we go to digital operating basics. I think that’s most of the GE digital story, but we can look at their strategy. Now in here, I think they were actually very knowledgeable. They were pursuing a strategy. Sorry, a strategy that was a bold strategy. If they had pulled it off, they would have become a Microsoft of the industrial ecosystem. I think it was too difficult of a strategy for a company with no digital capabilities or organizational behaviors. I would have told them if they asked, and I’m dealing with an industrial company on this exact. question right now. I would have told them don’t think about the ecosystem. Go with a simpler business model like IBM. Sell hardware with services which you already do but also with software packages. So we’re gonna sell this solar panel. You’re gonna sell the traditional maintenance contract and service contract but we are also gonna sell a subscription to a software product that and better and that’s we’re not gonna digitize and connect the whole ecosystem. We’re just gonna sell smart connected products. Which is kind of what Tesla is if you buy a Tesla, you have to pay for the Tesla, you can pay for services like maintenance, fix the battery, but you can also buy software subscriptions such as I will pay whatever it is like $10,000 at the time you buy the car to get the full. autonomous driving capabilities as opposed to the basic autonomous driving capabilities. So it’s hardware plus services plus software. I would have done that as the strategy and then three to five years down the road if everything’s going well let’s start talking about platforms and ecosystems. But that’s just a very difficult strategy. Anyways that’s kind of my diagnosis and I think that tees up nicely with the concept for today which is digital transformation. 70% digital operating basics, 10 to 15% tactic, I’m sorry, 10 to 15% strategy, 20%, five to 10% tactics. That’s a pretty good approach. They were too much into the strategy and they chose one that was too difficult and the stumbling was the tactics and the digital operating basics. Anyways, that’s kind of my take. And that is the content for today. As for me, it’s been a bit of a turbulent. week unfortunately which is a bit ironic because last week was like one of my best weeks ever and I’m talking about sort of life in Bangkok and I mentioned last week I was you know going out on the boat on the river with you know business school here it was just wonderful. Anyways that all got completely wrecked about two days after the really cool boat cruise. Just visa issues got If you’re gonna live in a country long term as a foreigner, you generally need a long term visa, and if you wanna work, you need work permit. And I had that all set up for years and it was fine. And then that all got wrecked. So suddenly I find myself having to either get a new visa with a different company in Thailand, or I got a bug out of the country in about two weeks, which is nobody’s fault. It was purely a miscommunication. It was set up one way. It turns out it was. Totally no one’s fault, just sort of a screw up. Anyways, that kind of threw my life upside down, so I’m scrambling a little bit this week, talking to companies, talking to universities, talking to the Board of Investment, which is a Thailand thing, trying to put that all together. It’ll be fine, it is kind of annoying. This is, if you’re curious about sort of, let’s call it global nomad living, which is awesome. By the way, it’s totally like the best. I’ve been doing it for a long time. There’s basically two tricks to this. If you can pull off the two tricks, two hacks, it all works out really, really well. And the two hacks are, you wanna separate your work from where you live. Where you work, where you live. You gotta break that connection. Because then you can move around, you can live one, you can basically maximize, you can optimize along two different lines. You can optimize your best possible lifestyle in one way, and you can optimize your work and earnings in another way, and those become two separate questions. So it turns out living in, let’s say Thailand, is awesome, but making money, let’s say in the US or Europe is awesome. I mean, you break the question into two different pieces, it all works out wonderfully. That’s sort of hack number one. The other hack, which is a bit more in the weeds, is you basically set up two to three different residences in different locations. And what that does, if you’re curious, is most countries are set up to allow people to visit four to five months as a tourist per year. It’s totally fine. If you stay more time in a country, you will eventually get pulled over by immigration, which has happened to me here in Thailand a couple years ago, where they kind of say, look, you’ve come into the country like 10 times. What are you doing? Because they basically don’t want people living somewhere as a tourist. They say, look, if you want to leave here, that’s cool. You got to go get a long-term visa, which is what I’m dealing with right now, which is totally reasonable. So if you have two homes, in two different places, you basically stay under that threshold forever and everything where you can live in Japan four to five months a year, you can live in Thailand four to five months a year, you can live in the EU four to five months. You also got to think about if you trigger tax residency, which is not just solely based on time. There can be some other metrics for a tax residency, but that’s generally the system. And if you do that, which is what I was planning on doing was home in Thailand. a home somewhere else and then a couple months probably in Rio for a year. That was my sort of life. And then everything works out fine and I was going to do that next year. Well, it turns out I got to do that next week. So that’s just sort of what happened, which it’ll all work out fine at the end of the day. But yeah, my wonderful life last week got turned upside down two days later. So I’m booking plane tickets. Looks like I’m going to Istanbul and Greece. for probably for July. If you know anyone that can help out with long-term visas in Thailand give me a call. I’d appreciate it. I’m talking with the Board of Investment right now. I’m talking with a couple universities. I’ll see if we can pull that together. Anyways that’s just been sort of my week. It’s been a little bit frantic but I’m pretty you know not to pat myself on the back but I’m pretty good at the scramble. I’m pretty good at like selling when I need to sell. and moving when I mean, I’ve been doing it for a long time. So when life gets a little messed up, I’m pretty good at sort of hustling around and scrambling and putting things together, just because I’ve done it enough times. Anyways, that’s me this week, but I hope everyone’s doing well. And I hope wherever you are, the COVID thing is all done. Everywhere else, it seems to be done. Thailand appears to be done. Japan is finally, I think, allowing tourists again. So just a couple of countries are left. So hopefully that’s all done, which makes my life as a sort of nomadic. person much easier. Anyways, that’s me. I hope everyone’s doing well. Take care and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.