In this class, I talk about Ant Financial/Alipay, AI factories and the basics of payment platforms.

You can listen here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

The previous articles I cite are:

- From Big, Dumb Bureaucracies to Zero-Human Operations: The Holy Grail of the Digital Age (pt 1 of 2)

- How Ant Financial / Alipay is Building an AI Factory in Financial Services (pt 2 of 2)

- #19 The Basics of Ant Financial and Payment Platforms

Concepts for this class:

- Advantages of Scale

- Economies of Scale and Scope

- Learning Advantages

- Disadvantages of Scale: Bureaucracy, Specialization, Scope, Scale, Complexity, Connectivity

- Payment Platforms

- AI Factories / Zero-Human Operations

Companies for this class:

- Ant Financial

- Alibaba

———-

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

——transcription below

:

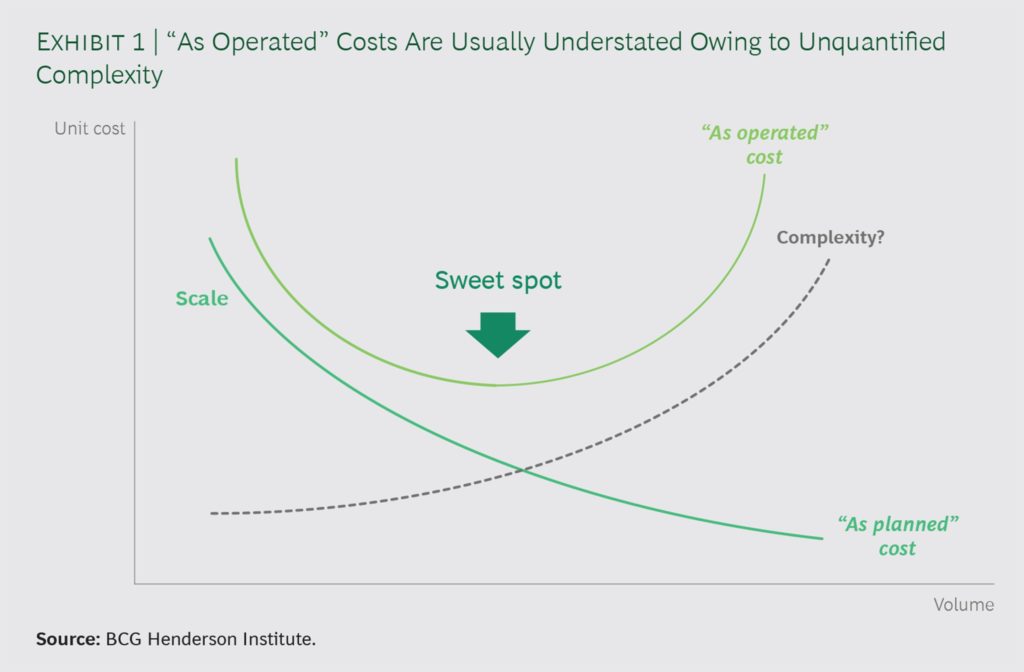

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the question for today’s class, how big is Ant Financial going to become? 150 billion US dollars, 250, 500? Could it be a trillion dollar company? We’ve seen a couple of these now. It’s a pretty amazing company being built. It’s mostly sort of hidden in terms of their numbers. It’s not public, obviously. And you don’t see a lot of clear numbers coming out of this, but I think if you just talk about the structure and what they’re building, it looks pretty huge. So that will be the topic today to sort of take apart and financial and talk a bit about payment platforms and go into some new areas about AI and sort of human-free operations. and it’s going to be a lot of fun. Well, I think it’s fun. Hopefully you think it’s fun. So that will be the topic for today. And we’re going to really touch on three to four important concepts. So for those of you that are subscribers, this is all going to go under learning goal number 19. And the main ideas we’re going to talk about are advantages of scale, which I’ve talked about that several times. There’s actually kind of a lot of them. We’ll talk about disadvantages of size and scale, which I’ve written about in some of the recent stuff, but we haven’t talked about here on the podcast. We will talk about AI factories, or what I’m also calling human free operations. And then we’ll talk about payment platforms, which is another type of platform. And this will be the first time we talk about that. We’ve done marketplaces, we’ve done coordination platforms, but you know, payments are pretty common and we’ll go into that one. So that’s kind of the four main concepts for today. which we will go into and build on over the next courses. And first, if you haven’t signed up, please do so. It would be much appreciated. You can go over to jeffthousen.com and sign up there and there’s a free 30 day trial. And if you sign up, you basically get a lot more content and a course outline. And I am gonna start giving homework assignments, which I’ll talk about in a sec. But it’s a more structured approach to sort of move you further and further. along in terms of your understanding and expertise over time. That’s the whole goal of the course. Let me talk about the homework assignment. This is for, you know, anyone who wants to do it, but definitely all the subscribers. And I’ve been thinking a lot about how to how to sort of help you move upward in your understanding. And that really is my bottom line for all of this, to make sure you’re getting smarter and sophisticated about that. If that’s not happening then I’m not doing my job. That is literally the only bottom line here. So I’ve laid out four levels of sort of understanding. Easy first steps, level two, level three, level four. And you know those of you who have signed up you’ve got that Excel. I’ve sent it to you in email. If you don’t have it just log in and you’ll see. And within each of those there’s really five main ideas in each level and you learn, you go up step by step by step. And under each sort of learning goal and each one, I’ve put certain articles to read, certain concepts, and I think it’s enough. I think the content’s there. I don’t think it’s overwhelming. I don’t think it takes a huge amount of time to just sort of go through a concept. But the thing I’ve been struggling with is, like, if you don’t try and use something, you tend to forget it. You know, you gotta try to use it. You gotta try to apply it. Ideally, you teach it. That’s actually the best way to learn anything is to teach it. But so what I’m going to start asking you to do for a lot of those that are in the class, look at whatever level you are on, which a lot of you is going to be easy first steps. Within that, you’ll see just a couple learning goals. Click on those learning goals, pick one and just skim through the articles. It’s probably a podcast and an article. Just skim through the article. It’s going to be a pretty straightforward idea. Try to find a company. that you think is an example of that concept. So let’s say it’s marketplace platforms, or let’s say it’s economies of scale or switching costs. Okay, try to think of a company that has switching costs that maybe you have dealt with. If you don’t have one you’ve dealt with, then just pick one of the ones I’ve talked about. And, you know, sort of try to take it apart. What is the switching costs? Like, can I describe it? If someone asks me, what is it? Could I explain it to them? and take yourself through it and try to apply it. And it’s even better if you can write it down, but at least try to find a company that has an example of that idea, and then maybe write two or three paragraphs of it. And that’s a good way to sort of test yourself and you realize certain parts you understood and certain parts you don’t. So that is kind of the homework assignment for this week. By next week’s podcast, whatever level you’re on, easy steps, level two, level three, level four, Take one of the ideas in there and try and go find an example in your own life. Anything you’re interested in. And then I’m going to push you every week to do another one. So I’m going to in theory sort of push you to go up step by step, step by step, step by step. So that’s the one for this week. Find an example of a company. Ideally write it down two to three paragraphs and do that by next week which will be about six days. Okay let’s talk about… Ant Financial. Now I posted a couple articles in the last week. The first one was called From Big Dumb Bureaucracies to Zero Human Operations. And this was on April 16th. This is under the member content. But I think I made this one public to everybody. Yeah, I think that one’s public to everybody. I kind of want to talk through that because there’s a couple of really important ideas and that will tee up Ant Financial. this all sort of leads to understanding what Ant Financial is doing. Okay, there was a Boston consulting group article that came out not too long ago. They write some pretty good stuff on competitive theory and digital. I don’t agree with, let’s say, half of it. They just come at it from a different set of frameworks, a different way of doing it. And they’re not Asia-China focused kind of like I am. So things are a bit different. But I think they have some good ideas. I try to keep an eye on what they’re doing. There’s a guy named Martin Reeves there at BCG who writes about this stuff. Very interesting stuff. And they basically put together this idea that said, when resilience is more important than efficiency. Okay. The argument they make, and I’m going to paraphrase it, is there’s a chart here which I’m going to put in the show notes. So if you’re watching this on your phone. look down below, they’ll either be the graphic or they’ll be the link to the graphic. And it basically shows your typical economies of scale slide, which is the y-axis is going to have unit cost and the x-axis is going to have volume and there’s going to be a sloping curve from upper left to lower right. Basically, when you have a low volume of something, if you’re a factory, your unit cost, cost per unit, is quite high. As you do more of it, you move to the right, higher volume, higher volume, generally your cost falls. Now there’s certain cases where that doesn’t happen, there’s certain cases where it does, but if you’re building a factory that tends to happen for multiple reasons, and therefore they say this is one of the big advantages of being bigger than your competitor is economies of scale. If you have a beer factory and I have a beer factory and we both serve you none, because you can’t really ship beer very far because the transportation costs make you unprofitable. So you’re pretty much competing locally with other brewers. If my beer factory is twice as big as yours, I am probably cheaper on a per unit basis than you are. Because there’s a lot of fixed costs in running a brewery and a bunch of warehouses and trucks. Okay, that’s kind of industrial age 101. That’s the basis of, hey, we all used to build things in little workshops. Let’s build big factories starting 150 years ago. Let’s build Model T cars in big factories. Let’s do mass production. And then let’s do mass distribution and then let’s do mass retail and mass consumer products. But it starts with mass production and cheaper. Okay, that’s pretty much true. And one of the big thinkers on this subject was actually Bruce Henderson, who is the founder of BCG. He wrote a lot about economies of scale. and he also wrote about learning advantages. So there’s actually, let me back it up one second, then I’ll get back to BCG. The idea is if you’re bigger than your competitor, you have advantages. There are big advantages to scale, size, and it’s not just the one I mentioned. There’s the one I just mentioned, which we call that economies of scale, which is usually about your fixed costs. And the person with the bigger volume, if you have roughly the same fixed cost, the cost per unit is lower. That’s economies of scale, but there’s other versions of advantages you get when you’re bigger than your competitor. Another one we talk about is economies of scope, different than economies of scale. Economies of scope is more like your proctor and gamble. You have one common marketing department. one common purchasing department, one common, let’s say R&D department, I’ll do a lot of that in P&G. And because you’ve got one centralized department that’s a big, huge fixed cost, you can apply that to lots of different types of products. So your scope of products is bigger than your competitor. That’s a little different than say economies of scale, which is more about your fixed costs in one line item. So people, you’ll hear this all the time, economies of scope, economies of scale. That’s a pretty good advantage. There are actually also learning advantages, which I’m not gonna go into, because that’s a whole subject. Generally, as you do more of something, you learn to do it cheaper. Not just that you’re bigger and you can outspend people and your machines are pushing out twice the volume of the other person’s machines. Your staff get smarter. They become more specialized. You know, IBM has a lot of learning advantages because they’re so big at doing software for critical processes of large companies. There’s just tremendous expertise. So they can do things faster, more efficiently. They learn quicker. Goldman Sachs has tremendous learning advantages because of specialization and how big they are. So there’s, and there’s different types of learning advantages. Some are simple, hey, you’re just cheaper because your company’s smarter. Some are often like, Steve Jobs, Apple under Steve Jobs had a learning advantage. Not only could they do things cheaper, they could invent the next thing more efficiently than other people because their company got not only good at doing things cheaper, they got better at inventing the newest thing. So iPod went to iPad, went to iPhone, went to ITV kind of, that’s another type of learning advantage. There’s multiple types of learning advantages that are pretty important. But you get a lot of advantages just from being bigger. That’s true. That sort of plays out in the chart I’ve shown you below, which is, you know, the curve goes from the upper left to the lower right. But if you look at this curve, you’ll see that there’s another curve that goes from the lower left to the upper right, which means… As you get more and more volume, as you move from left to right on the x-axis, certain costs start to actually increase. It turns out there are huge advantages to scale, no doubt. There are also disadvantages to scale. And as you get bigger, those disadvantages ultimately overcome the advantages and the two cost curves get you basically a U. If you’re looking at the chart, this is easier to understand than me explaining it to you. But it’s basically a you. As you increase in volume, your unit costs decrease up to a point and then they start to increase again. That’s a pretty good summary of scale, the advantages and disadvantages of scale. It’s a pretty good summary of the entire industrial area. There’s a reason why we don’t see car companies that are 80% of the entire market. and we see five or six of them, we see local car companies. There was a reason why when you go to your hometown, there’s not just one huge restaurant that has 10,000 restaurants on every street, and that’s it. Because that one restaurant got to scale and it wiped out their competitors. Now, I mean, that’s not how it works. We don’t see that. We don’t see companies with 10 million employees. We don’t see companies that generate 10,000 different products. We don’t see conglomerates that make everything from washing machines to saxophones to accountant services. I mean, we just, at a certain point, getting bigger doesn’t have any more advantages and you have disadvantages. So most companies that we look to over the last 100 years, they sort of max out at a certain size and they don’t get any bigger. Now that’s a lot of theory. Let me give you a concrete example. If you go to Omaha, Warren Buffett has a big furniture store there called the Nebraska Furniture Mart. It’s literally like the largest furniture store in the United States and it’s located in Omaha, which is funny because Omaha is a small place. And there’s a whole history behind this of how he bought this company from an elderly woman named Rose Blumkin, who he still talks about today. For those of you who are Buffett fanboys like me, or fangirls. They, you know, you’ll know about Rose Blumkin, who was a Russian immigrant who snuck out of Russia as a young teenage girl. She bribed the guards with vodka to get across the border. I think she crossed through China and eventually found her way to Omaha, which is a funny place to end up. And then she started a carpet store selling furniture and her thing, people call her Mrs. B, Rose Blumkin. And her thing was she is just… the most ruthless cost cutter you’ve ever seen. And she focused on furniture, but a lot also on carpets. I’ll explain that in a second, why carpets are kind of important. And she ran the store forever. And then, you know, one day she sort of, I think was in her 80s at this point, and Warren Buffett walked in and basically made her an offer, said, I’d like to buy 80% of your company. and I want you to stay on, because he was not just buying the company, he was also buying her. The management was a big part of what he was interested in. And he made a one to two page, I think it was a one page contract, and offered her a certain amount of money, having never seen the financials for the company. Now think how good of an investor you have to be to do that. A one page deal, having never seen the financials, and you’re confident enough to invest. I mean, that’s pretty awesome. but then, you know, he’s kind of smart. So he buys the company and she takes over and they slowly grow and grow and grow. And she’s just ruthless as a manager. And eventually she retires and her sons take over. And I guess she had some sort of falling out with them and she didn’t like how they were running the place. So she came back into business, must’ve been in her late eighties at that point, maybe even in her nineties. She opened a store across the street called, I think Mrs. B’s Furniture Warehouse, and started to compete with her sons who were running the company that Buffett owns. Eventually, Buffett worked it out. He showed up with some flowers and some chocolates and worked out a deal where she agreed to stop doing that. They merged the two companies together, and he said at that point, he did get a non-compete signed with her. So. and she spent the rest of her days, you know, working in the store and selling things. Now, why is the store so attractive? It has a lot to do with economies of scale. It has a lot to do with the fact that retail is a pretty tough business and I don’t think a lot of retail is attractive, but there’s a couple types of retail businesses that are attractive and one of them is furniture stores where the way people buy furniture they like to go see it. They don’t usually like to buy it online. They like to walk down, sit on the sofa, look at the carpet, see how it’s gonna look. Now that may change eventually, but that’s still mostly how people buy furniture. They want to buy it in person. Okay, if you’re gonna offer furniture as a retailer, then you have to have a huge showroom because it turns out furniture takes a lot of space. And they don’t wanna see one sofa. They wanna see 25 sofas. They want to see 40 sofas. And the more sofas you show them in your massive warehouse, you need a huge warehouse, you need a huge inventory, and you need a huge selling space. All of those things are fixed costs. So it’s a game of fixed costs. And if you’re more in the terms of if you’re a larger competitor, if you’re twice the size of your competitor, you can generally offer two things. that they can’t. You can offer a larger selection because they can’t afford to have this massive space with the same selection you have and you can offer a lower price because your per unit price is lower. Bigger volume, I’m twice as big as you are, my per unit price is lower and that’s sort of the killer offering that a smaller furniture store can’t match. And so what ends up happening is everybody goes to one furniture store in town. because there’s no reason to go anywhere else. Why would you go to the other furniture store that’s smaller? They’re not gonna have as big a selection and they won’t be cheaper. So all the traffic tends to concentrate. What does that mean? Well, that means you’re even bigger. So your economy of scale goes up and up and up and the market tends to consolidate to one or two major players within a local market and that’s exactly what happened with. Nebraska furniture mart and they dominate the marketplace and nobody can touch them on price or selection Now one of the reasons carpets the other fixed costs you actually have to think about within this is inventory and One of the problems with inventory for those of you who’ve ever done retail, which is a tough business is Your inventory can go obsolete depending on what you’re selling. I Used to work on a Saks with Avenue store, which is a you know fashion, Gucci, Prada, Christian Dior, Valentino, Tiffany jewelry, all that. And one of the problem was you would bring in the fall lineup of clothes. Here’s all our new Prada stuff. The day the season begins, the inventory starts decreasing in value because nobody wants last season’s stuff. So you have to move all your inventory as fast as possible because in six months your inventory is going to be worth half of what it was. It becomes obsolete due to fashion. Well, carpets, one of the nice things of carpets, the inventory doesn’t go obsolete. If you have good carpet, you can keep it, you can hold it, you don’t have to sell it this month. So you’ll see Buffett likes jewelry stores for the same reason. He has a big jewelry store in Omaha. And it’s similar. There’s a high fixed cost for inventory and it doesn’t go obsolete. And he offers the biggest selection of town in town of jewelry at a low price. So basically it’s the same equation. a big selection your competitors can’t meet, at low prices they can’t match, and it helps if your inventory doesn’t go obsolete. Okay, so that’s kind of an example of when being bigger collapses the market to one or two players. However, it doesn’t get you 100% of the market. You have an advantage of scale, but there are disadvantages to scale that usually lend the leading player to having 20, 30, 40% of the market. but you don’t get 100%. That’s the balancing of the advantages and disadvantages of scale. All right, one last point, and then I promise we’ll get to Ant Financial. Now, the disadvantages of scale, this is what the BCG article brought up. They basically said there are some disadvantages of scale, and the two that they mentioned were interconnectivity and volatile supply demand. Okay, what does that mean? That basically means if you’re running a business and you’re bigger than your competitor, you’re generally trying to be as efficient as possible in every segment of that. You want your retail to be very efficient. You want your factory to be very efficient. You want each machine in your factory, each step to be efficient. You’re maximizing efficiency part by part by part. That becomes harder to do if your business has a high degree of interconnectivity. Airlines would be an example of this. You can maximize how efficient you are in each airplane. You can maximize how efficient you are with your maintenance with all of that, every little step. But if your plane lands late in Dallas, it doesn’t just cost you money in Dallas, it ripples out through it in the system because that plane was probably then gonna fly to Austin. So now, Because you had a problem in one part of the business, it’s interconnected with the other parts. And when the plane doesn’t arrive in Austin on time because it didn’t arrive in Dallas, the staff that were on the plane might be moving on to a new plane. So then your staff are late. So when you have a business that’s highly interconnected, it is hard to maximize efficiency because what happens in one part of the business can ripple into another. So what most people end up doing is they just build in slack capacity. You just have extra planes flying, you have extra people waiting around because you can’t manage that efficiently. So one of the issues of when your company gets bigger and bigger and bigger is generally if you’re in a business with a lot of interconnectivity, those interconnections become very complicated and problems in one part of your business start impacting problems in other parts. So that’s an idea of why increasing scale can make you actually less efficient and have more problems. So that’s what they meant by the title of their article, when resilience, flexibilities, whatever they mean, is more important than efficiency. And the other thing they talk about is demand or supply that is volatile. If your consumers are changing their minds every week, oh, I don’t like this, then I like this, I don’t like that, it’s very hard to predict demand. Therefore, it’s very hard to predict your inventory. So you can’t manage your inventory that efficiently because you have to just have a lot of extra inventory because you don’t know what people are gonna buy next week. So certain businesses, as you get bigger, you have all these disadvantages of scale. Those are the two they mentioned. I don’t actually think those are the important ones. The ones I’ve mentioned, and I’ll give you the link to the article, I’m not gonna go through it all, but I basically mentioned four. You are vulnerable to specialists. As you get bigger, You are vulnerable to some very specialized niche player carving out part of your business. Newspapers. Newspapers used to bundle lots of types of information. This was economies of scope. Here’s the business section, here’s the technology section, here’s the classifieds, here’s the cartoons, here’s the sports section. A bundle, economies of scope, and then lo and behold, some specialized magazine comes along that only does sports and they carve out that part. So you leave yourself vulnerable to specialists. Businesses tend to become big dumb bureaucracies when they get beyond a certain point. I’ll talk about that. But when you put a lot of people together, politics starts to play out. Corruption starts to happen. Human beings, we seem to have a difficult time organizing beyond a certain point. We do political stuff. We fight. We become complicated. It’s Businesses at 10,000 run pretty well. Once you start to get businesses over 100,000 of them, most of them are not that well run. And businesses over, you know, what business can you think of that has 5 million employees? You know, we really do have a hard time as human beings organizing. So you get bureaucracy, you get corruption, the whole thing just becomes too complicated. This is why companies can’t. It’s very hard for conglomerates to do well because it’s… It’s hard to be CEO when you’re selling 10,000 different products. Baby shampoo, saxophones, cars, insurance, all of that. No CEO is smart enough to manage a business with all those different types of businesses. No company is smart enough to manage a business with 10,000 different products. It turns out our brains and our ability to organize doesn’t go up forever in terms of complexity. We can’t handle things beyond a certain point of complexity very well. Most of the really big companies you look at in the world are doing pretty simple products like beer or chocolate. You know, it’s, it’s hard for us to do complexity beyond as well. So I basically argued now we’re going to get to Ant Financial that the disadvantages of scale are. vulnerable to specialization, there’s scope. Too much scope is a disadvantage, too many products, too much scale is a disadvantage, too many employees, too much complexity and too much interconnectivity. All of those things increase as businesses get bigger and bigger and you get disadvantages of scale and it doesn’t work out. So that was the point of that chart, which brings us finally to Ant Financial. Because I think what Ant Financial is doing is possibly having all the advantages of scale and none of the disadvantages I just mentioned. I think they may be removing the second part of everything I just said, that they’re getting advantages of scale and they’ve figured out how to avoid all the disadvantages, which means they could in theory. grow without limit in terms of size, grow without limit in terms of scale, grow without limit in terms of connectivity and complexity. I think they might be doing this, which is the point of today’s class, which is how big could this company become? All right, Ant Financial. Now I am sort of obsessed with Ant Financial, but it’s hard to get information about this company. I visit Alibaba and Hanjo fairly regularly. I really enjoy talking with them. Just great people, so good at what they do. It’s really kind of a pleasure and they’re doing so many interesting things. It’s crazy. But I always ask about Ant Financial and I always ask about credit. You know, I always want to know like, okay, Singles Day was so-and-so, you know, it was $36, $38 billion worth of sales GMV in 2019. How much of that was done on credit? Because Ant Financial, which began as Alipay, right, payment processing, which was on their e-commerce site. And then it began offering credit and a whole bunch of other stuff I’ll go into, credit to consumers, hey, you can buy on installment, you can buy on credit and carry it. There’s also supplier credit, things like that. I always ask how much of that was on credit and they always tell me to basically, they’re not gonna tell me. I’ve asked so many times in so many different ways, you think I’d get tired of getting shot down, but yeah, they’ve never told me. To consumers on Taobao today, how much credit is actually being used? They know, I don’t think anybody outside of financial knows. What about to merchants? Installment payments is kind of a big deal. But Ant Financial is kind of the, I think in many ways, it is maybe the most exciting company coming out of China today, but it’s kind of like the quiet giant. One, you don’t know much about them because their numbers aren’t public. They’ve been expanding internationally very aggressively for the past three to four years. Everyone knows TikTok is going international. It’s in the news all the time. Ant Financial has been as aggressive for years and years. but it’s generally not reported. It has a lot to do with the fact that they do financial services in FinTech, and that really is a specialty. I mean, my expertise in FinTech taps out pretty quick. There’s a lot of regulation, there’s a lot of bureaucrac, there’s a lot of government aspects, which I just don’t know the regulations of how you do payment processing in India. I mean, I just don’t know what the rules are. So it is a bit of a specialty, but they’ve been expanding very aggressively in terms of the products they offer, and also in terms of geography, particularly in Asia. Big, big deal in Asia. They’ve tried to expand into the West. They tried to buy Moneygram out of, Moneygram is American, I believe, right? Western Union is American, I think Moneygram is too, and then CFI is the security oversight board blocked it out of the US. But they’ve been doing this, and everyone thinks they’re building a global payment network. where you can do payments and cross border and all of that, which is pretty much what Mark Zuckerberg wanted to build when he launched Libra, which doesn’t look like it’s going, well, it may go further than I think, but they’ve basically been doing that for years. Alipay, which is the payment processing, has 900 million users plus in China, plus probably another 200 million outside of China. So they’re over a billion people. that use this as consumer side. And then on the merchant side, on the SME side, you’re up to 100 million SMEs. So it’s already massive. Most of that is China. It’s increasingly becoming an Asia story. And if you run down the list of all the products they’ve offered, I mean, it’s just awesome. It’s really great. I mean, it’s, let’s say Ant Fortune, this is their… They’re basically wealth management product. Once someone’s doing payments for you, it’s very easy for them to say, hey, would you like a money market fund? Would you like to put your money in this investment product? Would you like to put your money in this? So they’ve started offering sort of comprehensive wealth management services. This was launched back in 2015. The one everyone talks about is UABAU, which is their money market fund, the largest money market fund in the world now. I mean, when they started this thing, they got about $80 billion under management in about the first six months. I mean, that’s unbelievable. Lots of Chinese institutions are involved. But under Antfortune, they’re offering this full suite of wealth management products. It’s growing, it’s growing. They have an online bank, a private online bank called MyBank. When China began offering private banking licenses a couple of years ago, they were among the first to get one. Only a couple were issued. Tencent got one, Alibaba got one. GBA, which is consumer loan service. There’s a bunch of them. I’m not gonna go through these. I’m not an financial expert. I know basically what other people know because it’s in the press, but I don’t have much expertise beyond that just because it’s, I don’t know how to get the data. Insurance, Financial Cloud, they do a Gemma credit. So scoring, you know, credit scores. I mean, there’s just a long list of products that are coming out. all very impressive. So it kind of has a lot of scope, i.e. economies of scope. It has scale, they’re big economies of scale. So it has kind of the classic things I was just talking about, but here’s the so what. Oh, let me tell you a little bit more. I looked at some of their cross-border stuff they’ve been doing. This is from when I visited their campus in… last year, end of last year, I kind of looked at what they were publishing there. And you know they have in Asia, here’s the ones they have that they do to do payment, cross-border payment, which is increasingly using blockchain I guess. They have Gcash, which is in the Philippines. They have Lazada, which is in Indonesia. They have Paytm in India, which is actually Paytm is pretty amazing. I think they kind of got paid, it’s the fourth largest digital wallet in the world by users. I mean Paytm in India is like 200, 300 million users now. I think Alibaba kind of just got lucky on that one. I don’t think that was really a plan. I think they just had an investment in Paytm and the management just really kind of rocked it. And they ended up having a stake in this pretty amazing digital wallet in India. QR codes, you know, you see those in Thailand, you see them in Malaysia now. QR codes are actually kind of funny. Like, you ever like? Who invented QR codes? It was invented, there’s a gentleman in Tokyo who worked, he was an engineer in the automotive industry in Japan, and he invented QR codes in the 90s as a way of doing inventory and other types of tracking within automotive. It was clever, you know, this two by two box that you could scan with, you know, sort of visually, and it’s been sitting around for 20 years, and then… Chinese companies kind of discovered it and used it as a payment mechanism. Yeah, that’s where QR codes come from. EasyPaisa, which is a digital wallet in Pakistan that is cross-border. Alipay Hong Kong, Kakao in South Korea. So I mean, they’re everywhere. February 2019, they acquired British International Money Transfer Services Provider World First for 700 million. And in November 2019, They basically launched a $1 billion fund to do more investment activities in Southeast Asia and India. So they are all in on going from China to Southeast Asia to India, financial services giant. But here’s the big so what. I mean, the big so what is on their brochures in their offices, you will see the numbers 310. That’s their kind of mantra, 3-1-0, which stands for three minute application, one second approval, zero humans involved. That’s 3-1-0, three minutes to apply for a loan, one second to get approval, zero humans involved in the process. And it’s that zero that I think is kind of the critical thing here. Because everything I just talked at you about for the last 20 minutes was this idea of There are tremendous advantages to scale, size, scope. But at a certain point, they are outweighed by disadvantages, which is why we don’t see 10 million person companies in the world. We don’t see companies that handle 10,000 products. You know, there’s limits based on the four I gave you were complexity, connectivity, scale, scope, bureaucracy, vulnerable to specialization. All those advantages, you know, sort of. That’s kind of the story of the industrial age, because that’s how humans work. That’s how we think. Our brains can’t handle beyond a certain point. We’re not good at organizing beyond a certain size. We argue, we get political, we have self-interest, all of that. Well, what if there’s zero humans involved in the processes? That’s three, one, zero. What if in the core process that your business does, which is making loans and approving them, and then collecting what within that process you have a zero human operation? One book that’s written about this, and it’s worth, I think it’s good, I don’t agree with a lot of it, let’s say 70%, but I think there’s a lot of interesting ideas in it. There’s a book called, Competing in the Age of AI. by Kareem Lakhani and Marco Iancitti. And they talk a lot about how, if you were to build a company, where the core processes that the company does, whether it’s issuing loans, making cars, selling products like shampoo, if there are no humans in that, if it’s all run by software, do all those disadvantages we just talked about go away? and then you could scale forever, maybe. They argue that as you do things with your software, the limitations on scale, scope, and learning disappear. Those are their three words. That’s the part I don’t really agree with. But they argue not only does those limitations go away, but you might actually even get better. The more searches you do on Google, the smarter Google gets. So volume… not only does it not have any weaknesses, you get better and better the bigger you get. Now let’s say scale. If you are processing a consumer loan, in three minutes to apply, which is what the person does, one minute or one second to approve, and then zero humans, is there any difference between approving five loans and approving five million? The software doesn’t know the difference. Does the software have any trouble with that increasing scale? Not at all. Why can’t it do 10 million? Why can’t it do 50 million loans? It doesn’t have those limitations. What about scope? What if instead of just offering one basic loan, two different types of mortgages, two credit cards, which is like a typical bank, right? What if you offer 10,000 different financial services products? The whole suite. Well that would be hard for humans to do. We’d have a hard time designing and managing and executing all those. You’d have to train all your staff. Your customer service would go down because your staff wouldn’t know all of the products anymore. If that’s all happening without humans with software, well software has no problem with complexity. When you go on Amazon or Alibaba, there are hundreds of thousands of items you can buy and the software handles it just fine. If you go into a physical store that sells 10,000 items, the layout’s not as good, you can’t find anything, you ask the service person, excuse me, where do I find this item? They don’t know, because there’s like millions of items or tens of thousands, they don’t know anything. Everything gets worse. But Amazon and Alibaba have no problem with scope of that size. So could a financial services platform with zero humans offer 10,000 different financial service products? to hundreds and hundreds of millions of people. Is it any more difficult than doing it at one tenth of that? It seems to me pretty straightforward. So these limits, and what about the connectivity issue? Well, that’s not a problem, because it turns out software is really good at talking to itself and talking to other software programs. You just integrate it and there you go. So do all those limits go away? And then we just have all upside of scale. So that brings us back to sort of the question for today’s class is how big could Ant Financial get if it’s a zero human operation, which is also sometimes called an AI factory. Could this financial services platform serve 2 billion people around the world in terms of payment, consumer products? and 500 other different services. What is stopping that from happening? You don’t have to open all those branches. Typically, to open a big bank, you gotta open a lot of branches, you gotta hire a ton of people. It takes decades and decades for the major banks like Bank of America and the US, Citibank, Bank of China. I mean, those things took decades to build. Everything I’ve just described to you about Ant Financial is six years old. Six years. How big could it get? Could they serve three billion people with these products? Could they sell 100,000 different types of financial services products? What is gonna stop that from happening? Now, I don’t actually have an answer for how big this company could get. I mean, ultimately you can’t get big beyond a certain point because you’ve run out of customers. You can only sell so many cans of soda in this world before there’s not enough human beings to drink the soda. So the market size eventually will limit you. But this idea of an AI factory financial services company is pretty amazing to think about it. And it’s in their main 310 headline. They are clearly thinking this way. So I just wanna tee that up. And the main idea for today, one of the main ideas, is this idea of AI factories, human free operations. You know, what businesses are going to move in this direction? How far can they go? Certain businesses you can’t because you need people. Now, this doesn’t mean when I say human free operations, I don’t mean people aren’t there. It’s just that they’re involved in designing the machine, maintaining the machine, overseeing it, but they’re not involved in the daily operational execution of the main products and services. That part happens seamlessly without anyone involved. So it can happen 24 hours a day, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. You know what’s actually like this is all these, these MoBike and OfoBikes that were around China for so long and the MoBikes are still there. Those were effectively human free operations. You know, the team built the system, the GPS, the bikes, the app, but they put the bikes on the street and then they could just leave them. And the bikes did the business for you with no, no human involvement. And people would ride them and ride them and ride them. And you know, you just sat there and collected your money. So it’s not. you know, like there’s no people, we’re just not in the operations. So that’s kind of the main, the other main idea for today is think about human-free operations, AI factories, and how far you can go in that direction. Okay, one last idea for today, and then I think that’s plenty. I wanna talk about payment platforms. I’ve talked about digital platforms as kind of the super predator of our time. They’re the animal on the landscape that nobody can compete with. The Indominus Rex, for those of you who watch the Jurassic Park, Jurassic World movies, just runs around the island eating everything because nothing can stop it. Well, that’s digital platforms. And I’ve teed up a couple of them at this point. I’ve teed up marketplace platforms, Alibaba, Amazon, eBay, companies like that, where the defining characteristic of a platform… is that you’re serving more than one user group at the same time. You’re not just serving consumers, hey, we’re selling chicken. We’re serving buyers and sellers of products. And our primary role is to enable interactions between these two user groups. And for those of you who have been doing this from the beginning, I talked about that as lowering coordination and transaction costs. Sort of Ronald Coast. idea of how to think about markets versus the theory of the firm. But marketplaces is an easy one to think about. And then I talked a little bit about coordination and standardization platforms and we talked about Zoom a little bit. If you’re not familiar with these talks, it’s okay. Just, you know, if you’re following along the course schedule, you will hit these as you move level to level. But another platform type. Now let me qualify this. There is a tendency to try and put platforms and say, oh, there’s only two types of platforms. There’s innovation platforms and there’s transaction platforms. And everything else is a subtype. You know, don’t try and put everything in two simple buckets in life. Life is more complicated. Business is complicated. There is no grand unified theory of business. It’s just a lot of ideas. And sometimes, you can use these frameworks and figure stuff out. And a lot of times you can’t, because it’s just chaos. It’s like life on the savanna. Sometimes animals just running around eating each other and whatever. And don’t try and come with a grand theory for all of it. It’s just not gonna work. So I have a short list of platform types and I just put payment platforms as a type. Now some people would argue, well, this is another type of transaction platform, therefore it’s a type of marketplace platform, whatever it’s, just call it payment platforms. I think it’s worth thinking about in its own right. Now a platform business model connects two user groups or three user groups or four user groups, but more than one. And when you do this, you get certain advantages like you get a chicken and an egg. You can subsidize pricing. You can sometimes get network effects. but not all platforms have network effects and not all network effects require platforms. Platform is a business model. It’s a type of network focused business model and sometimes you can get benefits, but not always. Now, payment platforms, you do tend to get all of the advantages, but payment platforms, one user group would be people who are paying for stuff and the other group is people who are receiving the money. Fine. You know. You could see these back in the 1960s when somebody came up with the idea for credit cards. I think Diners Club was first. I think Diners Club was technically the first and then American Express was the second in the late 60s. And you know they basically went around town and they went to a bunch of merchants restaurants and said will you please accept this credit card if someone brings it into you. Take this instead of money and they got a bunch of restaurants to sign up and then they went to a bunch of people And said if you use this card you can take into these restaurants and pay with this card And you know you had to get the the buyers and the sellers at the same time on the platform and you know took a lot of hustle and They did pretty well and then American Express came in and did it better And that’s one of the things about Platform business models. It’s usually not the first mover that wins In a lot of business, it’s like first mover is a big advantage. Platforms are so hard to put together. It is so hard to find the secret equation that balances the interests of both parties on the platform. Because if you give everything that the merchants want, the consumers aren’t happy. If you give everything the consumers want, the merchants aren’t happy. You’ve got to find the secret formula to get it to work. And it’s actually quite difficult, which is like… why Facebook wasn’t first to market. They were third or fourth. And the eventual winners in credit cards was not American Express, although they’ve done well, or Discover Your Diner’s Club. No, the eventual winners were MasterCard and Visa, and now Union Pay out of China. But MasterCard and Visa didn’t really take off until the 70s and 80s, so good 10 years later. Then they did quite well. So we could argue credit cards are a type of payment platform. But what about mobile payment? Isn’t that kind of a payment platform as a business model too? We get people to accept these. You know, you walk into any store in China, you show them your phone and they scan your QR code and that’s that. So you have the merchants involved, that’s a user group, and you have the consumers involved. That’s another, you know, user group. But they don’t use credit cards. That’s interesting. What about PayPal? Well PayPal got started, that’s Elon Musk’s first big hit and with Peter Thiel and they basically built that thing using credit cards. If you signed up for a PayPal account, you put in your credit card and they more or less piggybacked credit cards and they piggybacked eBay because people would go on eBay and they wouldn’t want to put on their credit card but so PayPal jumped in and said, well use us. Instead, put in your credit card to PayPal, it’s secure, it’s trusted, and then go on to eBay and put in your PayPal. So they actually piggybacked both because what does eBay have that PayPal wanted? Well, eBay was a two-sided marketplace platform. It had buyers and sellers. Exactly the two user groups that PayPal wanted. So by sort of rigging the game and piggybacking eBay, they ended up pulling those buyers and sellers onto their platform. So they kind of piggybacked and jump started off eBay, which eBay didn’t like. eBay eventually started, eventually acquired PayPal, brought them in-house, which you could argue is the exact opposite of what Jack Ma did with Ant Financial. When Alipay was built on top of Alibaba Taobao, they spun it out and… turned it into a separate company with a bigger mandate to create lots of financial services. And eventually when PayPal got spun out of eBay, it was sort of provoked by Carl Icahn, who was an activist investor. He used to be called a corporate raider, now they call them activists. He’s one of my people I follow, I think he’s just fantastic. And his argument on why to spin this thing out, PayPal out of eBay. had a lot to do with the fact that the fact that you’re in eBay is why you haven’t become a bigger financial services business. You know, you’re a fraction of what you should have become. Which is kind of the ant financial argument. Now it’s been spun out and now they’re doing things. But, you know, I can kind of make a short list here of, these are all platform business models. Good. They all have network effects. Two-sided indirect network effects the more people who take your card the better it is to the buyers The more people that are buyers the better it is to the merchants. So you get benefits what they call Indirect network effects or they call them secondary network effects just two-sided marketplace or two-sided payment platform indirect network effects and It is actually kind of linearly increasing in value Some network effects go on for a while and then they flatline some keep going up and up and up and up This is one of those cases. If you have a MasterCard, the more businesses in the United States that take your credit card, the better it is for you, it keeps getting better. The more businesses outside of the United States that take your credit card and will take it as payment, it becomes more valuable to you. It actually increases linearly to the whole planet. It’s a global network effect, which is why, when you start talking about payment platforms, everyone starts talking about global. that you wanna, you know, regional is good, but you wanna be a global player, and there’s only a handful of players out there that do payments. MasterCard, Visa, UnionPay, and now WeChat, and Alipay, and a couple others. Now, I would actually argue when you look at these, the business model is the same. It’s a platform business model, but if you look at the network they’re built upon, you actually see four to five different types. And we talked about this last week with how physical networks like railroads have shifted to things like digital networks like phone books. That’s different type of platform business model built on different types of networks. Most of the credit cards as business models were built on the fact that the banks have a network that connects them. There is a banking network out there. And credit cards, if you have a MasterCard, There’s usually, MasterCard will have a issuing bank and a sort of merchant bank. Citibank may issue credit cards to all the local merchants and they may also offer it to consumers and that’s who holds the credit cards. But when you make transactions, it gets sent to the bank and then the bank settles it within its banking network. The network that makes all that happen is the banking network. That’s what credit cards sit on top of. Mobile networks don’t have that. The network that enables mobile payment sits on the telecommunications network, not the banking network. If you have a mobile payment thing like Alipay, you transfer money from your bank into your mobile account, China Unicom, China Mobile, whatever you’re using, and then that’s what moves the money around. So it actually sits on a network made up of the telecommunication system, not the banking network. And there’s a couple other networks sitting out there. There’s merchant networks where companies like Walmart will connect with other Walmart’s, will connect with other retailers, and they have their own internal network and they may issue their own cards that operate on top of that network. You have remittance networks like UnionPay, or no, sorry, not UnionPay, Western Union, where Western Union will have outlets all over the world. And when you give money to Western Union in say, Singapore, Hong Kong, it then gets sent usually to the Philippines. That’s a private company network that does the transaction. And you could argue cash is a network. I mean someone gives you a hundred dollars, US dollars, it is understood that other companies will accept the hundred dollars. So there’s different types of networks that you can build these payment platforms on. And sometimes the company owns the network, sometimes the company piggybacks the network, sometimes the company didn’t have anything to do with the network. You know, cash is just cash and has existed for a long time. And that’s basically the last idea I wanted to sort of tee up today. One, the important one here is the idea that like, payment platforms are important business model to understand, very, very important. They, it turns out most of these digital players in Asia and the rest of the world, they’re all trying to move into payment. Mark Zuckerberg is desperately trying to get into payment. Very, very important. The networks that these things sit on are actually kind of funky. There’s several types. It’s constantly evolving, it’s changing very quickly. You know, when Warren Buffett gets asked about MasterCard and Visa and American Express, because he’s a big investor in those companies, he even says like, look, I have no idea what payment is gonna look like in five to 10 years. It’s just really hard to predict. There’s so many moving pieces happening right now that it’s hard to know what that’s gonna look like. It’s going global, there’s lots of products, it’s all digital now, you have digital currencies emerging, China’s launching one of those. So there’s a lot going on here, but it’s an important subject to know about. So that’s kind of the key other concept for today. So to review, the big ideas for today to take away, the advantages of scale. economies of scale, economies of scope, learning advantages we didn’t really talk about. The disadvantages of scale, which we’ve said several, payment platforms as another type of platform, and then this idea of human-free operations, companies that are AI factories that run entirely on software in their core operations. Those are kind of the big ideas. And then I wanted to tee up sort of the basics of Ant Financial. And I think… That is enough for today. Are you more excited? I think this stuff is so interesting. I’m totally obsessed. I’ve actually been having a fairly nice week here. Things are opening up in Bangkok. Things are starting to happen. It just makes me feel a lot better. I feel like we’re coming out of a, almost like coming out of a dark tunnel. You can kind of see the light at the end of the tunnel, which is nice. I got a great note the other day. the subscriber, you know who you are. I’ve already kinda, I sent out a quick hello. So one of the subscribers sent me a note that basically said, you know, I’ve learned more from you than I’ve learned from any teacher my entire life. That made my entire week, made my month, you know, that I really thank you for that. I mean, you know who you are. I won’t mention your name without your permission, but yeah, thank you for that. That actually means the world to me. As I’ve gotten older in life, I’ve, you know, I’m not so pickled or drenched in ambition like I was when I was younger and, you know, charging around trying to do everything and trying to, I don’t make a name or whatever that stuff is. And I get a lot more satisfaction out of seeing people do well who I’ve maybe helped a little bit along the way. I get a lot of satisfaction out of seeing my students. over the years who are moving up in private equity and strategy. And every now and then one of them hits the paper or something. I’m like, yeah, that’s great. That was, you know, I remember him. And, you know, you take a tiny bit of credit, not, you know, maybe a little bit. And so I find more and more satisfaction out of that as I’ve gotten older. Maybe that’s just a process of getting over myself, which is, yeah, I was much too ambitious as a young man. So yeah, anyways, I appreciate that for the comment. It really meant the world to me. But I hope everyone is doing well and staying safe. Definitely do the homework. If you’re a subscriber, do the homework. Go on to whatever level you are on. First steps, if you don’t have this, send me an email. I’ll send it right back to you. It’s all on the web page, but if it’s not readily available to you, just email me. That’s an easy solution. I will send it right to you. pick one item on there, one learning goal, and say this week I’m gonna read these two articles and listen to this and I’m gonna try and find a company that has this concept. And just do that and I will push you again next week to do another one and I’ll push you again and slowly we’ll move you up from first steps to level two to level three to level four. And anyways, I’m gonna be more pushy. That was my sort of takeaway from my thinking about this is I’m gonna start pushing a lot more. I’m already kind of pushy, but I’m going to be more so. So just accept it. And that’s it for me for this week. Everyone, thank you so much. Have a great week. Everyone stay safe, and I will talk to you again next week.