This week’s podcast is about digital content businesses, which are entirely digital economics. They can have great economics but absolutely need a moat.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Three digital content strategies I do like are:

- Network effects with long-tail of UGC. Such as YouTube and TikTok.

- Creates durable IP. Such as Disney.

- Service and community businesses that uses content.

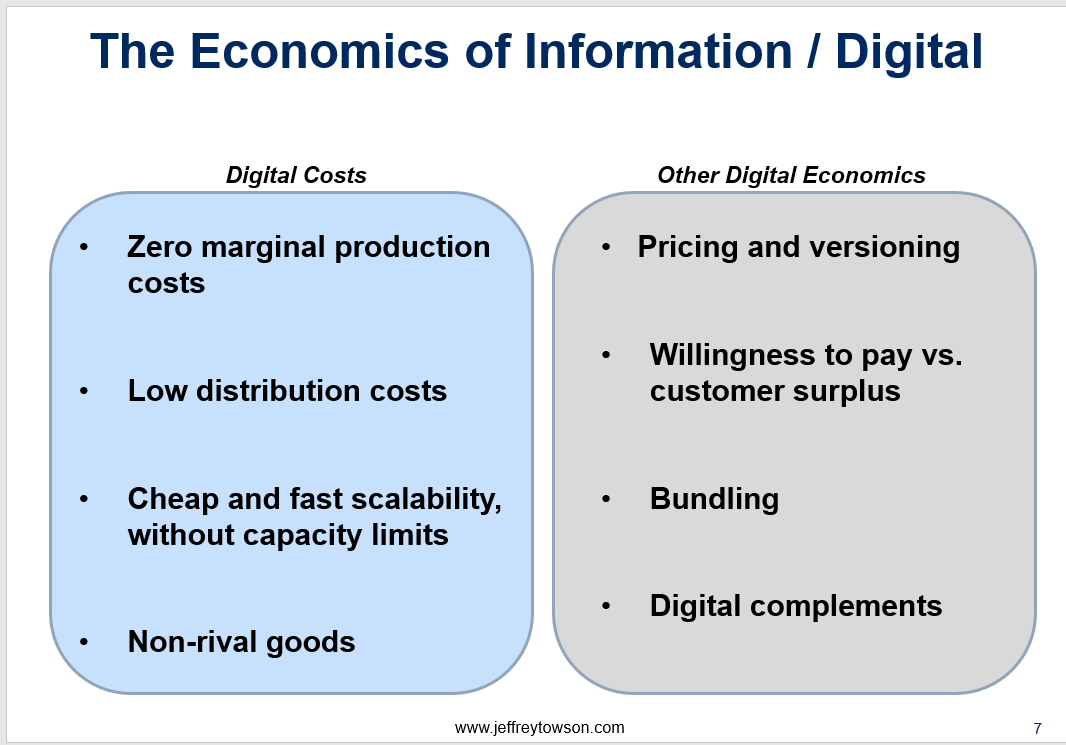

Here are the 8 ideas within digital economics I pay attention to:

——-

Related articles:

- Why I Really Like Amazon’s Strategy, Despite the Crap Consumer Experience (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Big Questions for GoTo (Gojek + Tokopedia) Going Forward (2 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- Why Netflix and Amazon Prime Don’t Have Long-Term Power. (2 of 2) (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Economics of Digital / Information

- Soft Advantages: Bundling and Cross-Selling

- Digital Operating Basics

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Netflix

- Amazon Prime Video

- Singapore Press Holding

Photo by freestocks on Unsplash

———-Transcription Below

:

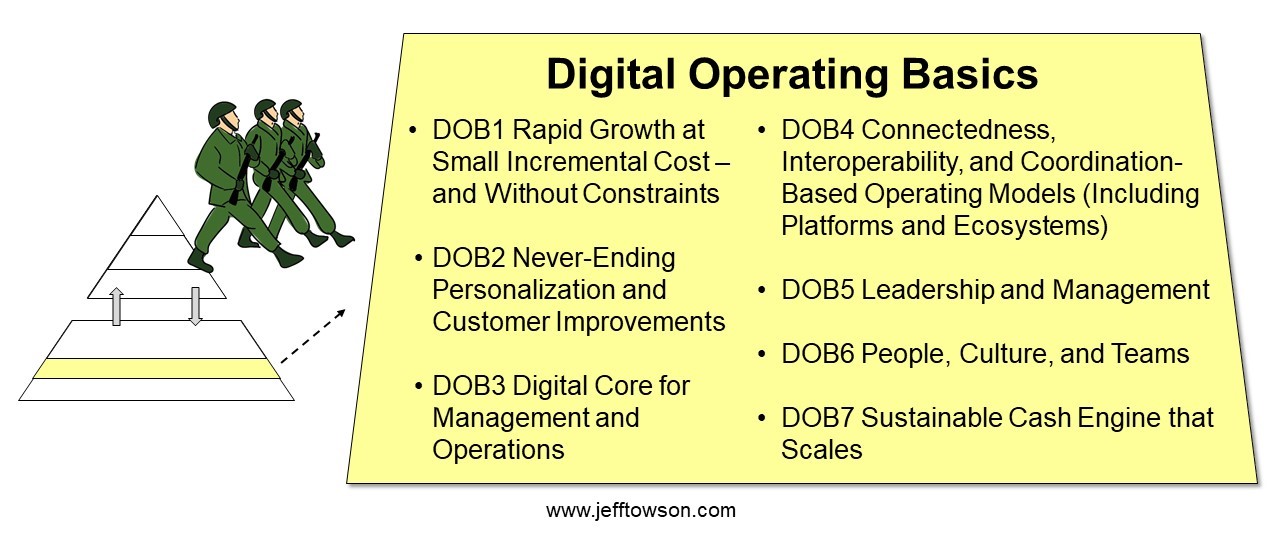

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast where we dissect the strategies of the best digital companies of the US, China and Asia. And the topic for today, why I don’t like Netflix, Singapore Press and most digital content businesses. And we could probably throw in Amazon Prime video as well. I don’t really like either of these in terms of their strategy, their competitive positioning and ultimately what I think is going to be their longer term strength, which is really what I focus on. That’s when business models and strategy play out is a bit over the longer term usually. And I just think it’s unattractive for various reasons. And I mean Netflix has been in the press a lot because of… you know, sort of increasing prices, decreasing user numbers somewhat, Disney Plus is popping up, people are starting to talk about HBO a lot more. I mean the whole space I just think is not terribly attractive and I’ll lay out the frameworks for why I’ve really thought that for kind of a long time, which is a bit of a contrast because Netflix in particular has often been pointed to as an example of like… digital strength and power and growth and all that. And I pretty much disagree with all of that. So I’ll lay out my thinking and give you a couple frameworks for that. Okay, no real housekeeping for today. Motes and Marathons books one through four are up on Amazon, eBook and paperback. Number five, I’m finishing up in the next couple days. And this is kind of a, someone asked me the other day, like, why are you writing five books with the same title? How are they different? And they’re not. It’s one big topic, almost like a textbook. I’ve just broken it into five, and it’s going to end up being 5.5 parts. There’ll be a number six, but it’s actually pretty short. And that will be the end of it. So yeah, it’s a book series on one topic, but there’s no real difference between part one, two, and three. It just takes a while to get through. Anyways, that’ll be up shortly. Let’s see, my standard disclaimer here, nothing in this podcast or in my writing or website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guess may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed by me may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Okay, now the concepts for today, there’s going to be a couple of them. I think these are hopefully going to be helpful. First one we’ll talk, there’s three of them basically. They’re always in the concept library. Number one is the economics of information and digital. And number two is digital operating basics. Number three, I haven’t really talked about before, which is sort of soft advantages. I’ll show you where that fits into the framework, but soft advantages around bundling and cross-selling. And I mean, I’ll give you the so what for the talk, and there’s no reason to go through the whole thing, that a lot of the strengths that companies like Netflix, Amazon Prime, that they talk about, is really just sort of what I put in the category of soft advantages, bundling, cross selling, things like that, which are good, but they’re not that powerful overall. And overwhelmingly what we’re seeing with, let’s say Amazon Prime and Netflix is just the digital operating basics being done with a couple of soft advantages, but no serious competitive advantages or moats. And we’re starting to see that play out in the competition. So I’ll go through that. Oh, one quick note. I got a…the podcast last week, the audio wasn’t awesome. I’m on the road, so I’m using a little travel microphone. I’m doing this from a hotel bed. Hopefully today will be better. Sorry about that last week. It was a little bit fuzzy, I think. Okay, so three concepts for today. They’re listed in the show notes. They’re in the show library. I’ll go through them one by one as we get through them. But I wanted to start with Singapore. I try in… Now, we try and talk about China, Asia, as well as the US and make comparisons. I find that’s pretty helpful. So I was reading a Harvard Business case about Singapore Press, which is a company in Singapore. It’s one of the largest traditional news organizations, particularly newspapers, but they have some other media as well. But sort of your… your standard media conglomerate that we’ve seen in country after country. There’s one in Indonesia, there’s one in China, there’s one in Turkey. These traditional companies, which 20 to 30 years ago were incredibly powerful businesses and digital has really wiped them out and most of them are struggling. And there is often not, you know, sometimes you get disrupted, which means you get replaced by a new type of business. like combustion engines are getting disrupted by electric vehicles. You know, it’s not that cars are going away, it’s just that certain companies are being replaced by others. We would call that more of a tech secular trend than a disruption maybe. Other times when a new technology comes along, the previous business just goes away, it’s gone. Nobody buys buggy whips anymore because horses, people don’t use them for transportation. the business is just gone. So you can kind of look at tech disruption or these sort of technology secular trends as it’s just going away or it’s being replaced by a newer model using different technology and the incumbents have very little ability to transition from there to there. The buggy whip companies did not become car companies. They just disappeared. However, the companies that used to make tires for horse drawn buggies they actually transitioned and they started making tires for Model Ts. So you want to think about that when you think about something like a press company, cable companies, news companies. They’re not disappearing, they’re just transforming to something else. And the key question then is can the previous incumbents make the transition or is it just too far? And I’ll give you an example. Like, traditional car companies are probably going to be able to go from combustion engines to electric. engines. They’re kind of set up to do that. I expect them to transition. I don’t see how most traditional car companies can go to autonomous vehicles, which is a completely different skill set. It’s all software. So they’ll make part of the transition. I don’t think they’re going to make the other one, but we’ll see. Okay, so let’s talk a little bit about Singapore because I’m an Asia guy. I have one foot in Asia, one foot in the US. A lot of China, but there’s other Southeast Asia, Thailand, Indonesia, really interesting. Okay, so you look at Singapore. For those of you who don’t spend a lot of time in Singapore, it’s awesome. It’s great fun. If you want to get really inspired about effective political leadership, which I think is kind of rare, that’s a bit cynical, look at Lee Kuan Yew’s… Go on YouTube, just type up Lee Kuan Yew and listen to him talk about anything from about 1965 to about 1990. Incredibly good thinker. Well, you know, he’s to a large degree the architect of modern Singapore, massive success story by any measure. A lot of what we see in Asia, South Korea and China for a long time was largely a copy of what Singapore had done. It’s just a lot bigger. Okay, so you look at Singapore today, five to six million people, but about one to two million of those are non-residents. It’s a fairly small city. The numbers are all amazing, 98%, 97%, literacy rates, multiracial, multilingual nation, no crime, no security issues, thriving capitalist system, although it’s under largely one-party rule, which is an interesting sort of example of a benign dictatorship. working very very well, which is not that uncommon. In a lot of smaller and especially developing countries, the sort of benign dictatorship model works quite well. But there’s always the risk that it tips over into something more bit hardcore. Anyways, English, Chinese language, Melee, Tamil, 74-75% of the residents are pretty much Chinese descent in some form. 13% melee and then India probably 10%, something like that. City-state amazing, forget crime, everything works beautifully. Now there’s always trade-offs there but a lot of this is very attractive. Okay, so then we get to the point. It turns out 90 plus, 95% of all households in Singapore are totally connected on the internet. They’re totally on their mobile phones. They’re spending three hours, four hours a day. They use it overwhelmingly for news. So when digital disruption happens in something like the news business, Singapore, like Silicon Valley, like New York, sort of ground zero for digital transformation because everybody’s on it. Okay, so you look, where do Singaporeans get their news? It’s kind of a mix. Overwhelmingly everyone’s on websites but 57% are still using television, 53% are still using print and let’s say 20% are on radio. So that’s kind of the backdrop for the fact that you have Singapore Press Holdings, SPH. It’s kind of a merger. It’s one of these companies that merged along the years. 1984, the Straits Times, for those of you who live in Singapore, famous newspaper, the Straits Times, very well-known, founded in 1975. And then you have Singapore News and Publications. They all sort of merged up as well as Singapore News Services and Times Publishing, Burhad. All of this merged up in 1984 into one media conglomerate. with a massive presence in news, which was overwhelmingly print newspapers. And this is very government involved. You’re not going to be a major news company in Singapore without some degree of government partnership, coordination. It’s the same in China, it’s the same in a lot of parts of the world. We do see lesser versions of this, you know, the BBC. Canadian broadcasting. So this idea that they’re totally independent, generally not the case, it’s generally a spectrum. And you could say the same thing in the US. So MSNBC and CNN pretty much speak for the government. If it’s Democrat, if it’s Republican, if it’s Fox News, these things are generally tied to some degree, it’s just a matter of how much. Okay. So you look at Singapore Press Holdings, 1980s, 1990s. You know, you’ve got the major English newspaper, Straits Times, you’ve got the major Chinese language daily, Lian Ha, Zhao Bao, you’ve got, I mean, they are just really sort of dominant. Okay, fast forward to 2017. They have moved beyond this and started to get into other things. They start, they’re listed on the Singapore Exchange. They’ve got their main business in media, which is now newspapers, magazines, websites, radio stations, advertising, outdoors. But they’ve also diversified into other things like properties, real estate, events, exhibition. They actually do a lot of aged care, healthcare and education. Again, that’s actually not that uncommon because these media companies were such cash cows. during the 70s, 80s, they diversified into other businesses, which turned out to be a really good move. So now SPF, I’m sorry, SPH, Singapore Press Holdings, four languages, print and digital formats, daily circulation is high but falling. So now we sort of, that’s the baseline. We see this pattern absolutely everywhere. 2013 to 2017. SPH starts seeing significant, well, an acceleration of their declines in their media revenue. 27%. You know, because that’s, look, people aren’t buying as many print newspapers as before. They’re more digital, which is a different business model. As the print numbers go down, the advertisers start shifting their attention. The print revenue starts to go down. We see the same pattern over and over and over. And who are they competing with? Well, it’s no longer the other major conglomerate of Singapore, which was actually MediaCorp, which is a subsidiary of Tomasig. It’s global newspapers. You know, Washington, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, they all went global as well, a small number. It’s Google, it’s Yahoo, it’s YouTube, it’s all free. There’s a slew of paid news sites out there. And then, of course, there’s social media. So the competitive picture changes dramatically. 2017, the company announces major layoffs which they call retrenchment. Even though the company is profitable, I mean they’re not losing money because they have these other businesses, but the percentage coming from media is dropping. 2016, daily newspaper circulation of Singapore is about 1.25 million. That’s down from 1.34 million in 2015. So you know… Decline, decline, disruption, everything shifting. So it’s still a profitable company, but revenue is declining. So what do they do? And this is such a standard situation. I get this question all the time from companies. What do you do when you’re facing major disruption, which is media, retail, a lot of consumer products companies, banks and financial services? And the hardest answer to that question, which I have to say every now and then is there’s nothing to do. It’s a major transformation and your company has very low probability of being able to make the jump. Go into real estate, go into healthcare, pivot. Well Singapore Press Holdings, they sort of do a digital first strategy. We’re going to invest and scale up new capabilities which means spending a lot of money. Digital capabilities, this is what they went after, digital capabilities, digital analytics, radio, video, and content marketing. Okay, they want to be a digital content company. And then second to that, you have to do lots and lots of organizational changes because you don’t have the people to do any of this, usually. So they start doing their digital first strategy which they say, quote, quality content, strategic partners, and technological innovations. Now that is actually very similar to the strategy of Disney. They go after high quality content, they build lots of partners, and they try to be a technology first company. They try and live on the frontier. And that has actually worked out very well for them. So they start doing bundling. We have a digital version, an all digital version, a digital plus print version. We post online first, we hire lots of international correspondents, and we’ve seen this strategy by press company, daily newspapers, across the world. It almost always fails. Okay. It’s very hard to make the transformation. Here’s the point I would put on top of that. Even if you win, you can’t win. And this is why I don’t like, which is the point of this podcast, this is why I don’t like digital content companies. I don’t like digital content businesses, even if they’re Netflix. Because even if you win, one, it’s impossible to make the transformation. Very, very hard. New York Times did it, Wall Street Journal did it, some companies did it. Very difficult. Even if you win, you end up with a very usually weak company. You don’t want to be in that space at all. That’s the answer. four times out of five. Which by the way is not pleasant news to give to a CEO and say look, so when I look at Singapore Press Holdings and they say we’re doing all this, I’m like look the business I like here is your aged healthcare company. I like your real estate business. Let’s do that. I know how to win in an old folks home. Hospice is actually quite a good business depending on what geography you’re in. I like all of those businesses better than I like this one. So rather than trying to do this massive transformation which has a low probability of success and is going to cost you a ton of money, don’t do it because even if you win, you end up in a very bad place. Anyways, that’s sort of my take of this whole podcast. So now I think you can keep an eye on this company. They’re publicly listed in Singapore. Why is it so bad in my opinion? Which brings me to sort of the first concept for today. and that is the economics of digital, which used to be called the economics of information, information economics. There’s textbooks going back to 1995 on this. Lots written about this. I’m going to summarize what I think is important in one slide. It’s in the show notes. You’ll see basically a PowerPoint slide with one, two, three, four, eight concepts that fit under the title of the economics of information and digital. You can see it in there in the notes. Basically once a business goes digital, the economics start to change. And sometimes this can be in part of the business like if a retailer goes digital, it’s going to change the economics of the interface, of the mobile app, of communication, of CRM, of marketing, of content. It’s going to change the economics there, but it is largely not going to change the economics of let’s say the supermarket. that goes with that. So part of the economics will change but part will not. When you’re talking about a digital content, digital content is all digital economics from top to bottom. There’s nothing left. Once Netflix started shipping things on DVDs or streaming there was no need for any physical stores with movies for rental or purchasing anymore. There just weren’t. It’s all gone. And you could say the same thing about music. There are no record stores anymore. It’s all gone. There are no book stores. They’re mostly gone. The economics are becoming 80, 90% digital, which means it’s a different game and you’re playing by different rules. So you have to understand what the economics of digital are. Most companies are not that extreme. Most companies are a mix of digital economics and traditional physical economics. And then you kind of work it out, which is kind of the reason like. The digitization of retail is actually a really good business. There’s a lot of great business models within that. The economics of digital and information, this is the key concept for today. It’s under the concept library. I’ve put a slide in the show notes that lists eight things. If you’ve got these eight, you’ve pretty much got it. I’ll just go through them. Number one on the list, zero marginal production costs. This is a lot of economics lingo. Basically, anytime you have a digital good, whether it’s content or software or something else made of bits and bytes, ones and zeros on a screen, you’ve got zero or almost zero marginal cost of production. Marginal means I’ve got one, what’s the price, the cost of creating the second one? Well, if it’s a digital book or the Avengers movie or whatever, control C, control V, now I’ve got two copies. It’s zero. The marginal cost. Not the total production cost. because sometimes the first copy is very expensive. You spend $200 million to make the Avengers movie. The second version is free, but the first version is very expensive. Even though in practice that’s generally viewed as a sunk cost, so even when you try and sell the second or third copy, you’re probably selling the Avengers for five to eight bucks. Okay, so you look at the economics of digital. The first one, low marginal production costs. Within that, you want to look at the cost of the first one as well. This is where you start to talk about the crowd, user generated content, Wikipedia, Juhu, Quora. Oftentimes, the first copy… can also be done for free if you’re clever and you have a clever business model where suddenly people are making TikTok videos for free and uploading them. So TikTok has a zero marginal production cost. Sharing the videos costs them nothing. In addition, the first copy of the video is not being done by TikTok. It’s being done by users who make their little videos. So they’ve got the best of both worlds. So does YouTube. So does Facebook. So does Twitter. If you look at the top digital content websites, apps in the world, six out of the top ten are based on user generated content. That’s really, really powerful. So you want to look at sort of both. Now the second idea on the list, low distribution costs. I don’t actually think, people talk about this so I’m mentioning it, I don’t actually think it’s very good. People say, look, I can send you an email with my content for a daily lecture for free. I can distribute this on Apple Podcasts for free. My distribution cost, not production, distribution is also zero. That is usually not true. It can be emails are free, Apple Podcasts are free. Most distribution, you end up paying a marketing cost. If I… put my ebook up on Amazon, I actually pay 30% to Amazon. Even though the distribution is zero, I have to pay Amazon because they control the traffic. So small distribution costs end up, you end up paying a large marketing, I would call it an engagement cost. So we’re kind of renaming distribution. It’s not really going away that much. Unless you have your own website, your own podcast. your own email, which is what I do. But most companies, nah, it’s not really the case. Okay, concept number three. Cheap and fast scalability without capacity limits. If you take the low marginal production costs, if you take low distribution costs sometimes, you can produce things at tremendous scale. Anytime you make anything in the physical world, you have to have a factory. If you want to scale up, you have to usually build another factory. Digital content has no capacity limits. I can blast an email to 500 people, 10,000 people, 100,000 people. It can go global. I don’t have a limit to my factory. That’s actually very powerful for companies like TikTok, Netflix, Disney Plus. You can get Disney or Netflix anywhere in the world. They went global with no limits to their capacity because their product is a digital content. Information economics. Okay, number four. I’m not going to go through all of these. Those are the big three, the ones I’ve said. Number four, rival versus non-rival goods. This is just arcane economics language. Rival versus non-rival. A rival good can only be used by one person at a time. If I’m eating an apple, no one else can eat the apple. If I’m sitting in an airline seat in the airplane, they can’t sell that seat to anyone else. A non-rival good is a video on YouTube. You can watch it, I can watch it, everyone can watch it at the same time. Well, digital content is usually non-rival. You can listen to this podcast, other people can listen at the same time. I think that’s most of the ones I wanted to go through. The other ones, I’ll list them. Pricing and versioning, willingness to pay versus customer surplus, bundling is a big one. I’ll talk about that shortly with Netflix and then digital compliments. I’m not going to go through the others. Okay, that is kind of the standard story for digital economics. Now why is that not awesome? You know, doesn’t Netflix have all this? Doesn’t Singapore Press have all this? Disney Plus, all of these companies? Well, it turns out there’s a bit of a catch. Because most things that are digital economics purely, content would be one type, but if you go on your iPhone or whatever, you have a lot of apps there that you’re not paying for. You have the clock, you have the alarm clock, you maybe are using translation, you’re doing .. Most of the apps on your phone which are digital economics from top to bottom are free. Most content online is free. Most news is free. Most videos are free. Why? Because as soon as you go to the digital economics, you say, oh my god, these are really attractive and powerful, which is true, but then you’ve got to price it. And if you go to standard economics theory, how do you price a good or service? You price the good or service based on its marginal cost. If you’re going to sell a pair of sneakers, you don’t look at all your costs, you look at the cost of goods sold, what was the last pair of sneakers I produced that cost me $4, I’m going to sell it for $6. You price in most businesses based on marginal cost. Well, I just got through telling you that the marginal reproduction cost of digital economics is zero. And it turns out, therefore, the appropriate price for most things that are digital economics is zero. that is actually the appropriate price. They’re free because they should be free. So you’ve got all these great economics, but you can’t charge anything for them. And that gets you into tremendous price wars. Most everything on the phones online is free. Now the way you get around that problem, which I won’t go into, is you have to price based on perceived value to the customer. What is this, the Avengers movie worth to Jeff on the opening weekend? What is it, the perceived value for him, the willingness to pay? And then you basically price on that, which is what a lot of these companies do. But The takeaway from all of this, which is what venture capitalists have been saying for 25 years, do not be in the software business without a moat. Just don’t do it. You’ve got to have a competitive advantage. If you’re in a business based on digital economics, of which content is one, you have got to have a barrier to the sea of competitors out there. Otherwise, your appropriate price is probably pretty close to zero. And that’s why if you look at software companies, the vast majority of them make no money. There’s a handful like Microsoft and others that make all the profits in the industry, everyone else makes zero. If you look at the vast majority of digital content companies, they all don’t make any money. There’s a small number that have powerful moats, those are the companies. So basically, the takeaway. Don’t be in the digital economics business without a moat. It’s absolutely brutal. Don’t do it. Most digital content companies, like let’s say Singapore Press, they don’t have one. So if I don’t see a massive moat, competitive advantage, I get very wary very quickly. So that’s sort of point number one. And that brings me to Netflix and Amazon Prime and really Disney Plus as well. Like, okay. why don’t I really like these companies? Well, because I’m gonna just run through, do they have a competitive advantage or not? So you look at the numbers and you say, well, Amazon Prime membership, which is not just the video. I mean, there’s Amazon e-commerce, there’s Amazon video, and then there’s Amazon Prime, but they really kind of link them all together. So if we look at Amazon Prime membership, that’s 200 million plus subscribers as of 2021. A lot of that is video, but not all of it. Okay, look at the same period, 2020, 2021. Netflix was at about 204 million subscribers worldwide. Disney Plus, around the same timeframe, 100 million. Now it’s much more. So all these companies are very, very large, getting tons of user engagement. Their cost structure is overwhelmingly digital economics. So we get to the question of, all right, you’ve got a killer product, people like it, the price is low. I don’t know if it’s killer, but it’s popular. We just start running down my six levels of digital competition. Does Netflix, let’s say, have a competitive advantage, which is level two? We look at the demand side. Are there searching costs? Are there switching costs? Does it have a powerful hold on people? The answer is by and large no, and most people don’t think it does. We look at the cost side. purchasing economies of scale, does it have economies of scale in fixed cost, particularly with the creation of content. And this has been a large part of the Netflix story for 10 years is we have economies of scale when we license content, which would be purchasing, and when we produce content in-house, which would be a fixed cost. So that would basically be, if you want to look at my list, CA-11 and CA-12. That has been the argument, we can spend more than others and we will distribute the costs across our huge user base and therefore our per unit content costs are lower than others. Now I don’t actually think that’s true. I think that’s the story. If you’re going to do the economies of scale game on the supply side, you need something where it’s just about spending money, like a utility. Like instead of 10 warehouses, I have 20 warehouses. Instead of having 10 factories, I have 20 factories. It’s got to be sort of simple. Netflix is not in the content business. It is in the creativity business. It is in the quality content business. That business doesn’t scale by spending money. You can’t say I have one pop band called The Beatles. If I spend twice as much money, I’ll have twice as many bands like The Beatles. It doesn’t work. If I pump out a hundred movies versus ten movies… they aren’t all going to be as good. Creativity doesn’t scale as easily. It can, but it’s very rare. So, and I think you see this in what people think about Netflix. Most of the shows suck. And in fact, it’s hard to find anything good to watch. That is very different than what Disney does, which is create high quality… small volume content that creates intellectual property. They’re still selling Beauty and the Beast 25 years later. Aladdin, they still have Iron Man. They are not in the high volume scale business when it comes to creativity. I think this is a major problem for Netflix, which I think people are now starting to recognize that they don’t really have economies of scale on the content side like they think they do or like people think they do. So I say on the competitive advantage side, Netflix, Amazon Prime, I don’t see it. They’ve got some soft strengths just like they have some soft strengths in their brand. It’s not worth nothing but it’s not an overwhelming barrier that is the kind of thing I want to see in digital economics. So we move down to level three, barriers to entry and soft advantages. This is the second concept for today because I’ve never really talked about soft advantages. If you look at my slide, barriers to entry, cost and timing of delivery, entry, things like that. SA1 is bundling, SA2 is cross-selling. One of the things you can do in a digital business is it’s very effective to bundle. I’m not going to offer you one TV show, two TV shows, I’m going to offer you 10,000 TV shows in one fee. That’s a bundle. We call it streaming, but it’s a bundle. I’ve got conditioner, let’s put them together in one package and charge one price, that’s a bundle. Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, Microsoft PowerPoint is a bundle. Because the marginal production costs are zero, you can bundle lots and lots of things together. So it’s a very powerful move when you’re dealing with digital content, digital economics. I don’t think it’s a barrier to entry. I think it’s good. but I call it a soft advantage. Hence, soft advantage one, bundling. The other one I list is soft advantage two, which is cross selling. If you’re logging into, I don’t know, Uber to get rides, it’s very easy to cross sell you Uber Eats. The customer acquisition costs are very, very low. So that’s an economic benefit, no doubt. I mean it plays out in your cost structure. So cross selling as well I consider very effective, but I don’t consider it a barrier to entry. I think it’s a soft advantage. So the two I’ve pointed out and this is the other concept for today is bundling and cross selling are both soft advantages. Netflix absolutely has those. In fact I think that’s most of their strength is right there. They can bundle 10,000 shows together and your old cable package did the same thing. in a way that there’s nothing you’re going to buy at Walmart that’s 10,000 things bundled together for one price, but you can do that with digital goods. And they’re very good at cross-selling because they have your attention, and that’s what Amazon is doing. It’s using Amazon Prime to cross-sell you from e-commerce into video, and it’s doing it quite well. Again, I think that’s good. I don’t think it’s overwhelming. Okay. We move further down the list, we get to the digital operating basics. This is what I think 80% of what is going on with Netflix. When you look at the digital operating basics, what is Netflix really known for? They’re known for their scale, it’s global. They’re known for being very, very cheap for a very big library. That’s a bundle. They’re known for being super convenient. You can watch it on any of your devices. You can cancel any time you want. It’s much easier than sitting in front of your television, which is only at home. You can watch it anywhere, any time, no ads. You can even skip through the credits. They make it super user friendly. OK. Those three things I just mentioned, if that’s most of the Netflix story, look at my digital operating basics. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Number one, digital operating basics in one. Rapid growth at small incremental cost and without constraints. That sounds a lot like Netflix. Number two, never ending personalization and customer improvements. That’s also a big part of the Netflix story. They personalize it to you. They’re always improving. Number three, digital core for your management and operations. Well, Netflix is a digital operation from top to bottom. It was designed that way. And then the other ones are connectedness, leadership, doesn’t really matter. And then number seven, sustainable cash engine that scales. Again, that’s Netflix. Membership subscriptions, it goes up. When I look at Netflix and Amazon Prime, what I see is digital operating basics one, two, three, and seven. That’s 80% of what’s going on. And it turns out that was an incredibly effective counter strategy to the traditional TV cable which most people pay $110 per month, Netflix is $8. Outside of that story, the bundling and cross-selling, I think, are significant soft advantages. That’s fine. That’s, to me, what Netflix looks like. That’s, to me, what Amazon Prime looks like. I think that’s a good model. I don’t think it’s awesome. And I don’t think there’s very much stopping other companies from entering and doing a similar model, which is exactly what we’ve seen from Disney Plus. It’s what we’re seeing from HBO. They don’t even have to do the same model of we offer 10,000 terrible TV shows. You can be a smaller niche thing like HBO. Smaller number of programs, but much better quality. This sort of picture and It’s a pretty brutal competition. Even the strongest players like Netflix, Amazon Prime, HBO are going to struggle. And even that is a small number. The vast majority of people creating content don’t even have that. They don’t have the global scale. They don’t have the bundle. So I think that’s most of what we’re seeing is increasing competition against Netflix. I think their economics are kind of deteriorating. And Everybody else is just struggling to survive. Now that to me does not look that different than Singapore Press. It kind of looks the same to me. It’s better for sure. It’s not awesome. So the three concepts for today, and I’ll give you a so what at the end. Three concepts for today, the economics of information and digital, soft advantages one and two, which is bundling and cross selling, and then the digital operating basics. OK. Let me give you something more useful rather than just saying, hey, I don’t really like these businesses. But this is by and large why I do not like purely digital economics unless it has a massive competitive advantage. And digital content is one version of that and it’s very rare to see a competitive advantage in digital content. You see it in other types of software, Adobe and others. It’s much better. When you’re, you’ve got digital economics but you’re really in the services business, not the content business. Okay. Last point and I’ll let you go. The last point is, okay, what content businesses do I like? The truth is I don’t like most retail business models, but there’s a small number, Walmart, that I really do like. This is the same. I don’t like most content businesses, digital content. There are at least three strategies I really do like, business models. Number one, if you’re in the content business but you have network effects. and a big long tail of user generated content. Network effects, that is a powerful business model. If you combine that with a lot of user generated content, that is very powerful. That’s YouTube. That’s TikTok. That’s Pinterest. That’s Instagram. All of those are awesome. And I think you can see that in the numbers. That is a content business I absolutely love. So I’ll put these in the show notes though, which business models I like. If I see powerful network effects and user generated content, fantastic. Number two, you’re in the digital content business but you are creating valuable and durable intellectual property. And that’s in my competitive advantage list under proprietary tech or intellectual property. That’s Disney. Disney doesn’t churn out content after content that’s all worth nothing five years later. A lot of it is TV shows for kids and stuff. But they’ve also got Iron Man, they’ve got Marvel, they’ve got Beauty and the Beast, they’ve got Cinderella, they’ve got Mickey Mouse from 60 years ago. More than that. Right? So if you’re in the digital content business but you’re creating intellectual property that is valuable, I like that one a lot. And that’s kind of what I’m doing a little bit. I mean I’m a niche content provider but my content is very specific to one thing and it’s sort of branded to me. Then they monetize that by licensing it, they put it on backpacks, they put it on toothbrushes, they’ve built theme parks around this intellectual property. So I like that. If there’s durable IP, which is usually specialty, it’s a niche category, I like that one a lot. Disney is an example of that. Third business, last one. If you are basically in the services business but you use content to support that, you could be in the community business as well. And if you’re going to build a community, you have to build it on content. So things like Reddit, Nike does this. If you’re a service business fundamentally or a community building business fundamentally, You’re going to be basing that to a large degree on content. And I do that as well. I mean, selling consulting services. Well, the people who call me, they all know me because of my content. McKinsey does the same thing. BCG does the exact same thing. Deloitte does the same thing. Lawyers do the same thing. A lot of professional services people are putting out a lot of content and then they monetize it through services. That’s a very good business model. Anyways, those are kind of the three I like. To a lesser degree, you can do products like L’Oreal, where you create a lot of content and you monetize by product sales. I don’t think it’s as powerful as services and community building, but it’s not bad. Anyways, those three business models, which are all digital content at the core, I think they’re great. All the rest, I am pretty afraid of. And I think that is the content for today. As for me, I am just on the road and hotel living. It’s gonna be, it’s been six, seven weeks since I left Bangkok. I was supposed to get back around October 1st and be there for a while. It looks like I’m not even gonna do that. It’s gonna be probably more Latin America and then off to Germany for a couple weeks. So, looks like not home till November. That’s three months. So yeah, it’s fun, I’m enjoying it. I’m sort of getting used to it because I used to live this way for such a long time and the last couple years I’ve been a bit of a homebody. So I’m getting used to doing everything on the road again which is great. Yeah, I think I’m probably going to keep doing this probably six to nine months a year. So anyways, lots of meetings, lots of companies. If you have any companies that you think are worth talking to, I’m meeting with quite a lot of them in Brazil and Germany for sure. I usually talk to you about digital strategy, transformation projects, it’s usually either consulting strategy consulting or training for staff and things like that. It was a lot of fun. If you have any companies you think are worth talking to, send me a note, I’d appreciate it. But other than that, I think that’s it for this week. I hope everyone is doing well. I’ll talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.