In this class, I talk about the basics of Didi and the importance of switching costs on the supplier side of the platform.

You can listen here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

- #15 Basics of Didi and Switching Costs

Pictures with Didi driver

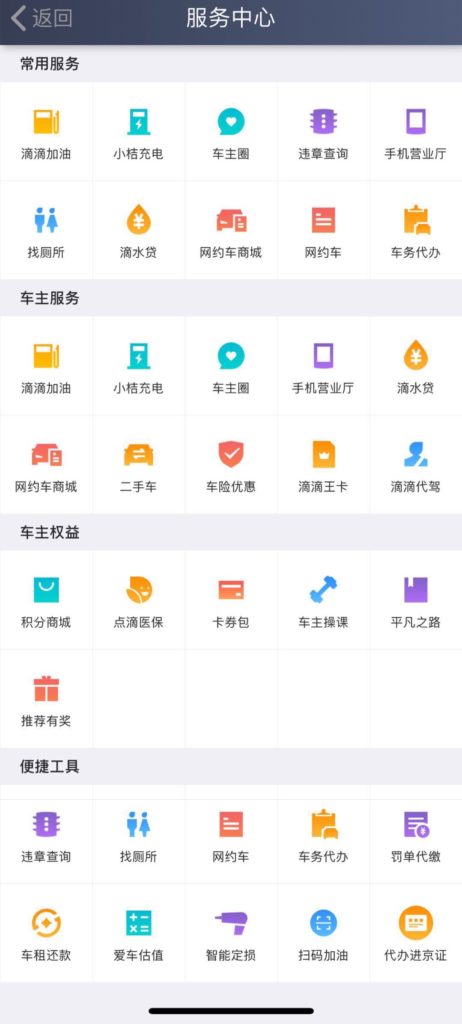

The services on the Didi driver app

Concepts for this class:

- Switching Costs

- Network Effects

- Digital Platforms: Marketplaces for Services

Companies for this class:

- Didi

- Uber

- Meituan

- Ctrip

———-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

——transcription below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the question for today, why does Didi need switching costs? Now this is gonna be a bit of a continuation of last week’s podcast, which was about services marketplaces. Some marketplaces like Alibaba sell products, some connect digital content like YouTube, Yoku, but last week we talked about marketplace platforms that connect services. and the companies we talked about were Maytwan, Alibaba Fliggy, which is their hotel business, and Ctrip. And within that, we talked a lot about hotels and restaurants and things like that, but we also kinda touched on transportation, which is another type of service. And I thought we’d sort of focus on that aspect today because ultimately, that’s what DD is doing. They’re a marketplace platform that does services specifically for mobility transportation. And we’ll talk about Uber as well, just because they’ve gone public, so we have the numbers. So that’ll be the question of how these are different and why switching costs are kind of the big idea to remember. Now, for those of you who are subscribers, the big two ideas to remember for this talk, concepts, are gonna be marketplace platforms for services, which we’ve talked about before. and also switching costs, which I’ve alluded to, but we haven’t really gone into it in any depth. It’s actually hugely important, not just in digital businesses, but pretty much most service businesses. And all of this is gonna go under learning goal number 15, which is the basics of DD and switching costs. For those of you sort of moving up the learning goals, this’ll be number 15. Okay, let’s get into the subject. But first, If you haven’t subscribed, please do so. I’d greatly appreciate it. You’re going to get a ton more content. You’re going to get a more systematic approach to sort of progressing, getting smarter, getting smarter, and all that’s available on jefftowson.com where there’s a 30 day free trial and as of this week an upgrade in the website because everyone agreed it was not very good. So that’s just been, we just did a quick upgrade last week and we’ll keep getting better and better on that. So go over jefftowson.com, sign up there. Alright, let’s get into the subject. So I think the story of Didi is fairly well known and it’s kind of gone quiet in the last really two years. There was a huge story 2015, 2016, 2017, that time period, a lot going on. Didi versus Quiety, big fight. Uber comes in, big fight. And then it kind of went quiet because they had the market and… People moved on to other things, but I’ll give you some of the basic numbers. And I was on the ground sort of down the street from all this during, during this period, so I’ll sort of tell you my experience, but you know, you basically had a DD Dachau, which is Dachau’s get a taxi, hail a taxi, and then DD basically sounds like a horn of a car, DD. And Didi was founded by Cheng Wei, who used to work at Alibaba and Alipay. And you know, executive, seasoned executive in the digital world of China. June, 2012, he launches, you know, Didi and basically a free for all bunch of companies jumped in. They had obviously seen what Uber was doing in the U S jumped out and. Other companies doing the same thing. What was different about China was, you know, in the West, Uber was really a disruptor. I mean, they went right after sort of private ride sharing. Let’s get regular folks in their cars driving. The taxis won’t like this at all and, you know, we’ll fight the government and be very aggressive in that way, which obviously Uber became famous for. That didn’t really happen in China. You know, the first service they went after was taxi hailing. Taxis in China are overwhelmed. I think they’re literally all owned by the government. So you don’t disrupt the government in China. I don’t think you disrupt the government in most places in the world, but you definitely don’t do it in China. So taxi hailing was sort of a way that taxis could get more business. And it was free, didn’t have to pay for it. If you wanted to taxi, you could use your app and get the taxi. And so it was kind of win-win. Nobody was getting hurt at that point. And by focusing on taxi hailing, they got a lot of usage. They got a lot of people, riders, they got a lot of drivers who were taxi drivers at that point. So the platform started to move. Before it came a little bit more aggressive and it got into the private ride hailing business where suddenly people were using their cars. And then the taxis had a problem with that. Local governments had a problem with that. And that was a little bit, that came years later. It was originally taxi hailing. So it moves along. Couple companies emerge, QuietE. And you saw sort of a money war, very common. Tencent backs Didi, Alibaba backs Quaidi. I mean, keep in mind, whenever you see these startup situations in China, about 50% of the venture capital money going into Chinese startups and digital is coming from the major tech platforms like Alibaba, Tencent and that. I mean, it’s about 50%. That is not something we see in the West. So partnering up with these big platforms is a big deal and often the market ends up looking that way where, you know, Ullama is owned by Alibaba and then May Duan is partnered with Tencent. You see that scenario a lot. Now what was different in this case is they ended up partnering. And they merged together and you got Didi Quaidi. They merged together and suddenly Alibaba and Tencent were on the same team. You had this one dominant player. The vast majority of taxi hailing, 90 plus percent was theirs. Private ride hailing, which was still not legal for a long time, but it was kind of happening anyways, most of that. And then Uber jumped in sort of late in the game, which was actually very impressive. I think they did a good job. Jumped in, spent a lot of money, came to, they were serious players, but unfortunately for them, DD had really, I think, top tier management. Chang Wei was in charge, but then Jin Liu came over from Goldman Sachs and they basically didn’t make any mistakes. They were out in front. They had a lot of money. They were very good at raising and they were pretty much flawless. If they had screwed up, Uber might have had an opening, but they never screwed up. And slowly over time, both sides sort of sued for peace. Uber didn’t get the market they dreamed of. but they went home with approximately 20% of Didi, which was a phenomenal deal. From a financial return, you spend 18 months and $2 billion and you walk on with 18 to 20% of Didi. That’s an unbelievable deal. But their goal was not a financial return, it was market share. They didn’t get that, but you don’t always get the gold medal in life. Sometimes the silver medal’s pretty good too and they got the silver medal. 2016. They basically partner up with Uber in China. Uber goes home. Didi has the market. And they start becoming a full mobility player. So it’s everything. It’s ride sharing, it’s taxis, it’s black car service, it’s bicycles, it’s commuter buses. I mean, they’re trying to do a full mobility solution, everything you might need in life. And they started raising a spectacular amount of money right after they sort of… settled with Uber and merged up. And I remember writing about this at the time. Like they were raising, you know, I think they had about $9 billion cash on hand. And my question is, what in the world are they gonna do with all that money? Because they don’t have a competitor. What private company raises nine to $10 billion with no competitors left? And I was really curious what they were gonna do and what they did. Well, they did several things. But one of the big things they did is they started going international. They started making investments in local champions in Southeast Asia and Latin America and Africa and Eastern Europe. And they sort of built the anti Uber Alliance around the world. Did very, very well. This didn’t get a lot of press, but Uber basically got rocked pretty much everywhere. Russia, Southeast Asia, India. everywhere pretty much but latin america they got beaten back and they pretty much retreated to the united states. North america and parts of south america mostly brazil and mexico which are the two largest markets in that geography. So many was this kind of slow steady grind away where didi was just actually didi and soft bank. We’re raising money just sort of fighting fighting fighting. Putting basically capital and technology into these local champions. didn’t get a lot of press. I actually looked into it quite a bit. I went and visited these companies out in Mexico and Brazil and to see what they were doing. And it was pretty impressive. That was kind of the story. And then DD went into bike sharing. They did that originally through OFO, but that didn’t work out. And then they, they bought Blue Go Go out of some quasi bankruptcy. And then they launched DD bikes. They started doing sort of financial services and then they launched something very, very interesting. which was Xiaoju Automotive Services, which was basically, if you look at the Didi app, it looks a lot like the Uber app for a rider. Do you wanna ride? Where do you wanna go? Do you wanna bicycle? Do you wanna a car? Do you wanna a taxi? What do you want? But if you look at the app that drivers use, it’s actually pretty amazing. And I met with one of their drivers. I sorta talked with their media relations folks and I spent some time hanging out with one of their drivers in Shanghai. And the services they started to provide to drivers were really unbelievable. I mean, everything you can possibly think of, they had, where do you buy your gas? Well, there’s an app for that and they get discounted gas because it turns out DD drivers, you know, a huge amount of gas and maintenance for your car and government registrations and licensure. And if you want a loan to buy a car and it turns out, I asked them this too, you know, what percentage of DD drivers want to own their own car? And it’s basically all of them, which is not the case in somewhere like Mexico or Brazil. And then these drivers are starting to create their own little small companies where several other drivers will work for them, even though they are DD drivers. You become like a small business person with your own little fleet of five to 10 drivers, and you might provide them with cars and things. So a lot of the drivers started to become small business people with their own little companies. So they’re letting drivers really build careers on this platform. Some drivers, not all of them. So there’s a whole slew of these services that they started offering. And then you look at the numbers and the numbers are, they’re pretty amazing. You’re talking about 500, 600 million monthly average users. You’re talking about tens of millions of drivers just in China. And then increasingly going international with their own direct services in Mexico, Brazil, somewhat in Japan and Australia, but mostly not. And I mean, it’s kind of an amazing story. And that’s, you know, the Dee Dee story. And then they had some safety issues a year or so ago. And they focused a lot on safety as a, you know, their number one strategic goal was safety. And there’s a lot of press on that. Okay. Now the problem of course is we don’t have the numbers, right? Nobody knows the numbers. They’ve made some comments about how much they make or lose. unclear but in 2019 D I’m sorry uber went public so we got to look at uber’s numbers and Everyone was not pleased that The numbers aren’t pretty. I mean there’s no way around it and Ride-sharing kind of went from the hottest best type of platform I mean this was the tech giant the two tech platforms everyone talked about Airbnb and D I’m sorry uber in the West And then they looked at the numbers and people’s opinions started to change. And then SoftBank had some issues with WeWork and the bloomers off the rows and a lot of negativity on that. Now, I think it’s actually both better and sort of worse than people are saying. And I’ll give you my take. But OK, so let’s say we look at Uber’s numbers coming out 2019. They go public. Their S1 comes out. In their S1, they say we’re doing 14 million trips per day, 91 million monthly average users operating in about 700 cities, mostly North America, South America by volume. Not by revenue, but by, well, by revenue in North America, but not South America. Okay, so dramatically smaller than Didi in terms of rides and users. Dramatically smaller, one fifth the size. Didi dwarfs them on a user’s… activity and really data level. And I’ve been kind of saying, when you build these platform business models where you’re connecting two different user groups, in this case, drivers and writers, you’re building that platform on three core intangible assets which are number of users, activity and data. So DD dwarfs Uber on these metrics. When you look at Uber’s numbers, the other thing you notice is they’re much more of a pure play. I mean, they are, we do rides, that’s what they do. They do transportation, they do mobility. They’ve got a big story about this, about how it’s, you know, only 1% of rides in a typical city are done in ride sharing right now, so there’s a potential upside that’s huge, all of that. They have the big ride sharing slash new mobility play. They also do Uber Eats, which is interesting, because we just talked about Maytwan. How Maytuan is not a pure play service, like we just do one thing, they do lots and lots of services. C-Trip, I argued, was a pure play. They just do hospitality and tourism, hotels, flights, things like that. Maytuan is going for a full suite of different services, and then Uber’s a little bit in between. They’re overwhelmingly a ride-sharing transportation service, but they’re sort of edging into deliveries, restaurants, things like that. That’s Uber Seats. And then they’ve got Uber Freight, which is kind of very small, not a big deal in terms of their numbers. And you know, you look at kind of why are they strong and the story you hear. And this is this is the story you heard before they went public and it is still largely true. The story they had was we have unbelievable growth against a massive opportunity, which is in fact true. Their numbers are going up like a rocket ship. They are very, very impressive. Their revenue, let’s say 2016. This is Uber was three point five billion. their revenue in 2018, 9.2 billion. So a massive surge in revenue, and they have a network effect as a two-sided platform that is connecting drivers and riders. And the idea is you have a network effect, the more riders you have, in theory it makes it better for the drivers. The more drivers you have, you get a couple benefits, you get more supply. If there’s more drivers on the road, your wait time is less. and your fares should be lower because people will accept a little bit lower price because there’s more competition. So if you have more supply you get shorter wait times, cheaper price. That in theory should get you more riders because the service gets better. More riders means you expand the market that gets you more drivers. That’s the flywheel, the network effect. That was their story before they went public. That and the massive growth and that is in fact true. The problem. not all network effects are equal. Some are street, some are very strong, some are somewhat weak, some are local, some are international. And it turns out Uber has a very weak network effect. Some people argue it doesn’t have one at all, I think it does. I think it is mostly a local effect. Hotels are an international or a regional network effect. The more hotels you offer in Asia, the better it is for everyone traveling in Asia. the more rides you offer, drivers you offer in Asia doesn’t make a lot of difference to those of us sitting in Bangkok or Beijing because I just want to ride downtown, I don’t care. So mostly local and also it asymptotes very quickly, which is, you know, the more drivers you offer, the value to me doesn’t keep going up and up and up and up. If there’s a thousand drivers within 10 minutes of my apartment, doesn’t help me. All I really want. Look, if there’s 25, 50, and when I say, oh, I need a ride, and it says a rider will be there in five minutes, that’s enough. Anything beyond that doesn’t help me. So the value doesn’t keep growing up, going up, it sort of flatlines very, very quickly. And that’s a little bit of their story. And that turns out to be a problem. So they’ve got a lot of good things, and then they’ve got some bad things. So more on their financials. This is from 2019 numbers. I mean, the revenue is great. If you look at the revenue, I mean, their take rate, that’s the phrase people use, take rate. You know, you buy a trip on Uber, about 20% of that revenue goes to Uber directly, and they get paid first, which is important. But that’s usually about 20%. D is actually cheaper. I mean, they take 15%, depending on their strategy at that moment. But if you look at their revenue, 2016, you know. $3.8 billion 2018-2019 they’re up to 10, 11, 12 billion so very good top line growth and that’s after the drivers have been paid. So the money’s already gone to the drivers, they’re cut. This is just Uber’s share of the business. They do actually have some fairly significant sort of costs of revenue. About 50% of that money they do end up paying out in various forms to things like insurance which is not insignificant. payment processing fees, credit card fees, driver incentives, keeping people on there. So there actually are some costs. This is not an 80% gross profit business like hotels were. Hotel reservations, gross profit 80%. Drivers, there’s a more physical operational aspect to this so the gross profits more in the range of 50% at this point in time, although that can change. Then you have a lot of operational support, about 12%. And big surprise there. their big expenses than sales and marketing, 28, you know, huge spending on sales and marketing. And that turns out to be the problem people talk about because in the West, which is not the case in China, you have two competitors, Uber and Lyft, and they are constantly fighting each other for riders, and they’re constantly fighting each other for drivers. And they do that with marketing spend. You give incentives to drivers, you give discounts to riders. and you’re always fighting for them. And the people who study this stuff, the digital strategy people, the phrase they use, which I don’t think is a good word, but they call it multi-homing, ease of multi-homing. If one user group, let’s say the writers, can easily switch between two platforms, can live on both platforms, can have multiple homes, multi-homing, it makes the platform more competitive as opposed to something like Facebook where you’re just in one place. I don’t think multi-homing is a very good concept, but you’ll hear it all the time. They’ll talk about ease of multi-homing on the rider side, ease of multi-homing on the driver side, and therefore there’s more competition. So you’ll hear that. And that plays out in marketing spend and people are always switching fat back and forth. And that is mostly true. Drivers will switch back and forth very, very quickly if they think they can get a better deal. And in particular. you know if they think they can make more need drivers will just basically switch from one phone on their dash to the other phone and they’ll use lift instead of uber their balance sheet is actually not bad like the income statements a little bit ugly because they’re losing money based in that result of the income statement is they’re losing a lot of money three billion dollars per year that range the work the balance sheet is not terrible the working capital is actually quite nice they do have a decent amount of debt but not you know It’s not pretty in terms of profitability, but the revenue line is good, but the level of competition means they’re spending like crazy and everyone’s losing money. And that’s kind of the story of Uber, is they’ve been losing a tremendous amount of money for a long time. So everyone in the West is talking about can Uber ever make money? Now we could assume some of that is true for Didi. I’ll give you my take on that at the end, but the big difference of course is Didi doesn’t have a competitor. They are overwhelmingly 90 plus percent of the market. Meituan jumped in there a little bit for a while. You see some meta ride sharing plays, but basically they don’t have that competitive situation. So massive increase in volume, probably revenue, and they don’t have a direct competitor who they’re in a death match with in terms of pricing and spending. But that’s about how I would look at DD right now. Okay, let’s get into some theory. Now the two sort of key ideas, the two concepts for this are switching costs and marketplace platforms for services, not products. Now my standard approach always is, I always, you know, I put on the consumer glasses, I put on the user, how does this look from a consumer? What does a consumer care about? What is their process? You know, how do they use this pipe, pay for this? Do they come back? All I sort of just walk myself through usually the consumer process, but This is a multi-sided platform. There’s actually two user groups. On one side, there are the consumers, which I just mentioned, but on the other side, there’s the drivers. So you have to walk yourself through the process for both user groups in this case. Now, the consumer view, how is that different? How, I mean, how does this, if I’m just need a ride, I go out on the street, I need to get a ride, maybe it’s raining, maybe I get to get to work, maybe I get to get an airport. What does the consumer really care about? and you can sort of think it in your head or you can just look at the financials and the company will usually tell you what the main competitive factors are. They’ll usually give you language. It’s very useful to look at their language. So if you look at Uber, they say they compete on price because it turns out people are pretty price sensitive on this. They care about wait time. Waiting for 10 minutes, people switch over to the other app and they try the other one. three to four minutes people wait. They care about reliability. You know, if I gotta go to the airport, I have to be reasonably comfortable that when I walk out with my suitcase on the street, that I can get a ride. Because if I can’t count on my ability to get the ride, you know, that’s not great if you’ve got an 8 a.m. flight and suddenly you’re on the street at 6 a.m. and you don’t know how you’re gonna get there. So reliability is an aspect. Price is an aspect. Wait time, which I would say is really convenience, usability is, and those are pretty much the main factors. There’s others like safety is important, and not having a car that stinks is important. There’s other stuff, but those are kind of the main ones. And I talked about this exact same sort of profile when we talked about Mobike and Ofo, because that’s pretty much what they’ll care about there too. And I described this as an access business where you’re not buying a bicycle. you’re looking to access an asset that someone else owns. And when it’s an access business, whether it’s getting a taxi or staying in someone’s apartment instead of a hotel or getting a ride to the airport, generally people are caring about our price and convenience. Those are the kind of the two factors. And ironically, which was interesting when the folks went on from doing mobility to doing luck in coffee, which was the same management team. That was basically their pitch was, you know, our luck in coffee is low price and convenience and standardized quality. That’s literally their pitch in their filing, which is exactly the same pitch you see for a mobility service, like word for word, which I thought was funny, because that was their background. Okay, so that’s kind of the view of what consumers care about. And then you’ve got to look at it from the driver’s side. What does the driver care about? Well, the driver cares about making money. The driver cares about flexibility, that they can work when they want to work. They care about, you know, are there going to be rides? Am I going to be sitting in my car on call and I don’t get any rides? So they sort of care about guaranteed income or reliable income. They care about price a lot. They will switch very, very quickly. And most of these drivers, and I’ve asked this in like four countries, most of these drivers come and go very, very quickly. It’s like call center agents. You’re always hiring, they’re always disappearing. There’s a huge churn. After six weeks, two months, three months, 80% of your people are gone. It can be that high. and you have problems with them, you have to do safety checks, license checks, insurance checks, all of that. So you’re always having a lot of operational aspects of checking and bringing drivers on and then they leave. But there is a core 20 to 30% that are actually high quality drivers who get very good ratings who will stay. And that’s actually the people you want. You wanna keep them on your platform and companies like DD in particular offer a lot of services to this group to keep them. And they care about a lot of interesting things. I interviewed some of these folks in Mexico and what they actually cared about in Mexico more than, well, price is always number one, fees are number one. But what they also cared about was insurance. That they wanted insurance, health insurance for their family. That was a big deal in Mexico. When I talked to drivers in China, what they cared about was the ability to buy your own car. Actually, people in Mexico, the drivers didn’t care about owning their own car. And what there was, there was a separate user group. that would buy cars and then rent them to drivers. So there’s actually another user group. It was drivers, car owners, and riders. We didn’t see that in China as much. In China, most people own their cars or they want them. And the drivers all actually work together. Like the drivers have a chat function on their phone and they chat with each other all day long and they have a team. So there’s team leaders who have 10, 15 drivers under them that they’re training. And when they get complaints, which happens, that’s a big problem for them, the leader will deal with the complaint for the driver. So there’s actually a lot of interesting stuff going on on the driver’s side that they care about. But it’s mostly about making money, having flexibility in their work schedule, things like that. Okay, so you look at that process, that’s interesting. And then we can look at this idea that, how is this different, if I’m a consumer, Am I gonna, you know, if there’s a service like Maytuan, which wants to offer ride sharing, but also offers restaurants, movie tickets, beauty treatments, flights, hotels, do I care that it’s bundled together in one service like Maytuan, or is it better if it’s a standalone service like DD, where DD is the ultimate mobility app? Everything I need in life to get from here to there, I go to DD. If I need a bike, I need a taxi, I need a car, I need a metro ticket, I need a bus ticket, I need a van to the airport, I need ride pooling, whatever I need, that’s DD, versus, which is a specialized function in mobility, versus a general service platform like Metuan. Does it help me if they start bundling those together or not? I don’t know. Maybe that’s good, maybe it’s a function, and we’ll see if that plays out. The other thing, and this is actually, I think, the key thing on the consumer side people don’t talk about, I don’t actually think it’s multi-homing. I don’t think it’s the fact that I can switch from Lyft to Uber. If that’s important, I don’t think that’s the big one. I think the biggest one impacting Uber is low-cost substitutes. I can get a ride downtown, or I can take the metro for $2. It’s longer, it’s less convenient, I gotta walk five blocks, but it’s $2. I can take the bus, lots of people take the bus. There are public services that are low-cost substitutes for this service, and that, you know, this is a standard Warren Buffett question. When you’re looking at a product or service, are there low-cost substitutes? Because if there are, that effectively puts a ceiling. on how much you can charge people. Because if you keep raising your rates, eventually people say, no, I’ll just take the bus. That puts a pretty hard ceiling for most users on your pricing. And unfortunately, drivers will not work below a certain amount of payment either. So you have a floor as well. If you pay drivers too little, they walk away. So they may be stuck within a band of what they can charge that doesn’t let them get to profitability in the United States. And then you have the competition with Lyft. So I think when I look at the consumer view, I think about this idea of what do consumers care about? Reliability, convenience, price. I think about substitutes as a potential option. And then there’s this competitive dynamic. And then the driver side is a lot more interesting. So that’s sort of the consumer view. Okay, so let’s look at the competitor view now. This is my standard process. look at the consumer view or the user view and then take it apart from the competitor view. If I was a competitor in this trying to get in this business well run well funded could I break in? Could I take 10%? Because if I can do that it’s going to change their behavior. It’s going to change their ability to make profits because they don’t have that much power. It’s sort of an assessment of how fortified are you. Now when you talk about the competitive view for. Uber and people say the same about Didi. Everyone points to the network effect. The idea is if you have a network effect, the market tends to collapse to a winner take all or a winner take most scenario. You get one player, you get two players, three players. You don’t get 10. There isn’t, you know, 50 of these companies the same way there’s 50 restaurants in every part of town. Because. By definition, if you have more drivers, your service is more valuable to the users. It’s a better service. If a bunch of people go to one restaurant, it doesn’t make the food taste better to everyone else, such that everyone likes that restaurant because the food tastes better. That happens in network effects. The service is actually superior. There’s more drivers available. There’s more services available. There’s no more products available. The service gets better the more people use it, so. the market very quickly collapses to a couple players, sometimes one player, but usually not. Usually it’s a couple, call that winner take most. And that’s why there is such a fierce competition when a business like this emerge and you see these companies like Uber and QuietE, Reid Hoffman at LinkedIn, the founder of LinkedIn, he calls this Blitz scaling, where you’ve gotta get to scale first because whoever gets to scale first wins everything. So there’s just this very vicious money war. We spend, we spend, we spend, we get the first. It’s game over. Now, so people talk about network effects, but I’ve sort of said, look, network effects are not all equal. Are they international? Are they regional? Are they local? Are they linear? Are they exponential? Are they asymptotic? How do they work out? Do they change over time? Now, a lot of the network effect has a lot, has to do with how frequently you use something. People always say network effect is how many people, how many users. It’s usually not about users. It’s usually about activity of users. A smaller number of users who are very active, like people who stay in hotels, actually people don’t stay in hotels that often. So if you say, I have a huge amount of consumers who stay in hotels, that’s actually not that useful because most people don’t stay in hotels every week. They stay a couple of times a year. But if you say, look, I have a small number of super users of hotels who are always in hotels, high frequency. that’s actually more valuable to the hotels. So the power of the network effect is not always about users, and it’s usually about activity levels. Sometimes it is about number of users, like WeChat and things, you can connect to more people, but often it’s about activity. Okay, that’s one aspect of the competitive dynamic of network effects. I think it’s significant, I don’t think it’s all powerful like it is in other businesses. The two aspects of the competitive view I want you to think about are the two key ideas for today’s talk, which is marketplace platforms for services and switching costs. Now, last podcast was about marketplace platforms. I’ve called platforms, digital platforms, the super predators of business. They’re the animal that can eat everything. They’re totally devastating. That’s Amazon, that’s Alibaba. They’re amazing. Usually people think about products. We’re buying, we’re selling products to people, that’s Alibaba. More and more it’s becoming about services, which was last week’s talk. That’s Metuan, they’re the Alibaba of services, or they wanna be. Ctrip is in the services business, but it’s a specialty. DD is in the services business, but again, it’s a specialty in this case, mobility. If you build a robust marketplace platform for services, How formidable is that to a new entrant? And well, we can look at users, we can look at frequency and we can look at data. Those are the intangible assets on which you build a platform. We can look at things like how fragmented is the supply side? If you are doing hotels to consumers, it’s actually pretty good because hotels are a very fragmented business, lots and lots of SMEs. If you’re doing… marketplace between airline tickets and consumers, it’s not very good because there’s only like 20 airlines, 30 airlines. So the platform has doesn’t have a lot of power if you’re only talking about 20 suppliers of the service. You want millions of suppliers. Well, the ride-sharing business actually looks quite good because you have millions, you know, tens of millions of drivers. So there’s a lot of it’s a very fragmented business on the driver side. The taxi companies not so much. It’s actually pretty consolidated So you look at fragmented versus consolidated and you look at standardized versus differentiated services and this is actually the big difference between say Maytuan and DD and C trip really Hotels are a very differentiated service When you when you look at what hotel do you want to stay in in Beijing or Jakarta or wherever? You look at a lot of factors you look at is it on the beach? Is it a big place because I have a family and we all need to go? Is it on this street near this famous site? Because I hear that’s good. Is it cheap? Is it like a bunk bed somewhere? I mean, there’s a lot of factors you care about and hotels are very, very different and what you want is very, very different. So there’s a lot of differentiation in the service. That’s why I think that’s aspect of Ctrip’s business is very attractive and Maytwan’s as well and Alibaba’s as well. But when you move into flights. It’s a pretty much a commodity service. All you really want is the time of the flight and the price. Maybe that’s pretty much it. There’s not a lot of differentiated, it’s kind of a commodity. Well, most transportation is a commodity service. It’s a standardized service. And you know you can tell this when you use Uber or Didi because they don’t even ask you to pick the driver. Have you ever noticed that when you go on C-Trip or Expedia? They show you a big long list of hotels you can look at and you scan through them and you read the reviews and you make a decision. Their value is a lot in the search process. Uber doesn’t even ask you. They assign you a driver. There’s no search process going on for you to go through. They basically just do automatic matching. I wanna go here, bam, your driver pops up. Here’s who you should wait for. because it’s a commodity service. There’s no reason to even have you make the choice. It’s all the same. So you notice that on a lot of transportation services. It’s a commodity service. They do the matching for you and they just tell you who’s coming. That’s not how it works on shopping for goods. It’s not how it works for shopping for fashion. It’s not how it works for finding a hotel. It’s not for finding a restaurant for dinner. You’re very engaged. So that’s a big sort of red flag. And then you have things like the chicken and the egg problem. That one of the reasons a marketplace platform, a marketplace platform can be powerful even without a network effect. Because there is what they call the chicken and the egg phenomenon. To start a platform business, you need a bunch of drivers. But to get the drivers, you need a bunch of riders. Because you go to the drivers and you say, please sign up for my service. And they say, how many people use your service? And you say, well, none. That’s not good, they don’t want to sign up. So you go to the riders, please sign up for my service. They say, how many drivers do you have? None. The first step in a platform business model is actually quite difficult. You gotta get, it’s a chicken and an egg problem. So even if you don’t have a network effect, the fact that it’s a platform business model creates a hurdle to entry that is difficult for competitors to break into. And if you do have a network effect on top of that, it’s even worse. So. You know, they have, even if they don’t have a network effect, even if Uber doesn’t have one, like people say they don’t, I think they do. I just think it’s fairly weak. Even if they don’t, they have a platform business model, which has inherent strengths in it. So I’d say that’s something to think about. Platform business models for services have their own strengths. They can be differentiated services like hotels, or they can be commodity services like transportation. So that’s kind of concept number one for today. The other concept, which I think is the most important one, is switching costs. And switching costs, they’ve been around forever. There’s nothing new about this. We’ve seen switching costs in all types of businesses for a long time. When you hire your accountant for your business, they come in and they do your books. And then at the end of the year, they say, by the way, for next year, we’re raising our prices 10%. And you think, ah man, that stinks, I don’t like that. And you think over, I should find a new accountant. And then you realize, you know what? It’s gonna be a pain to switch all my numbers. They’re gonna have to get up to speed on my numbers. They know my numbers. Eh, all right, I’ll just stay. That’s a switching cost. A switching cost is like, a switching cost gives the business the ability to raise the prices a little bit, and you take it. Now if the accountant comes to you and says, I’m gonna raise my prices 30%, most people are like, you know what, forget you, I’m switching. It doesn’t mean you can gouge people, but if you can raise your prices three to five to 10% every year, and let’s say your operating margin is 10%, you’ve just doubled your profits. It’s an ability to premium price that gives you really abnormally high return on invested capital. And it also gives you stable market share. That’s the two hallmarks of a switching cost. If someone tells you they have a switching cost, look at their return on invested capital. Look at their profitability. It should be higher than others. It shouldn’t be 5%, 8%. It should be 18%. That means they’re able to premium price a little bit and their customers don’t switch. And then look at their market share. It should be stable. Their customers should be retained. If you see people jumping in and out of their business, if you see high churn rate, a lot of customers leaving, doesn’t matter what they say, they don’t have switching costs. And switching costs can be lots of different types. Usually people talk about it like, let’s say in software, I mean, the ultimate switching costs is Microsoft Windows. Like you buy the computer, Windows is in there. You know, you have to pay for Microsoft Office or whatever and they gouge you, it’s incredibly expensive. It’s ridiculously expensive how much Word costs. And you wanna switch, but how do you switch? Are you gonna replace Unix on your, you know, Word on your computer? Are you gonna get rid of Office and you’re getting Unix? And forget it, it’s next to impossible, unless you’re a computer software guy or girl. You have no idea how to do that. So you pay $500 or $300 from Microsoft Office, which sucks. That’s a pretty severe switching cost. Very few companies can do that. A more reasonable type of switching cost is sort of a contractual obligation. If you wanna buy a table, let’s say this is B2B. If you wanna buy a table for your business, you don’t sign a two-year contract with the table manufacturer that says, anytime I need new tables, I’ll buy from you. or I promise you I’ll buy 10 tables over the next year. Now you call them up this month and you buy the table and then say, if I need any more, I’ll send you a purchase order. You just do month to month, whatever you need you buy. Some businesses, you get these multi-year contracts. Zoom, you know, this video conferencing app that’s doing so well right now. You know, they sign up businesses to use their, you know, their video conferencing thing and they get multi-year contracts. That basically, now when that company wants to switch, it’s pretty hard to switch, you’ve signed a multi-year contract. Insurance companies can do this. There’s a lot of this stuff on the B2B side. So you can look at contractual contracts, I’m sorry, contractual commitments. You can look at things like durable purchases, like I bought the big video, let’s say the photocopy machine from Hewlett Packard. That was $1,000. Put it in the office, put it in your home. and now I have to buy ink cartridges. Well, I guess I could switch to another company and buy cheaper ink cartridges, which is where they kind of get you on the ink cartridges. But I’ve already bought the big machine. The big durable purchase sort of locks you into the smaller purchases, and they get you with 10 to 20% price increases on that, and you can’t do much about it. Dollar shave truck, a lot of these like Gillette and these companies try and do this where they buy the nice razor handle and then you buy the blades and they’re a little pricey. So durable purchases. If you’re training your employees, let’s say for software, software is a good example. You know, you’ve trained your employees to work on CAD design. They know how to use it. They’re trained on this accounting software. I could switch to another software. But then I have to train all my employees again. They’ve already invested time and energy and expertise in how to do this. It doesn’t have to be software. It could be, you know, we’ve trained, let’s say auto dealers for how to use this particular machine to spray the color. When we finish fixing a car, we have to paint the car before the customer picks it up and we got to spray it so the, the color of the fender we just fixed matches. The rest of the car, you can’t give someone their car back. and it’s blue but then the fender’s a little bit off blue. People hate that. So you sell them these machines for color spraying and you train the employees for how to use that. And you can switch the machine out but then you gotta train them on the new machine. So there can be a lot of training costs. Dentists get trained on various types of tools they’re comfortable with, they stick with them. Information and databases. If we’re selling you data that you use as a hedge fund or you use as a marketing company, or you sell to your consulting clients, you could switch to another type of data. Hedge fund people can switch off Bloomberg Terminals to another type of information provider. Bloomberg Terminals is very expensive. But they’re trained on this, they’re comfortable with the data. So when Bloomberg comes back and says, we’re gonna raise our prices 10%, they kind of say, I don’t like it, but all right. loyalty programs you go down to the yogurt shop and they give you a little card and they stamp the card and You get six yogurts on your you know card and if you get another three yogurts you get the free one That’s a switching cost. I could go to the other yogurt place, but I’m gonna get the free one I get points airline miles. These are all attempts to keep you in So that you don’t switch quickly back and forth and there’s lots of different versions of these But generally what you’re looking for is you’re looking for something that’s going to increase the cost, the time required, or just sort of the level of hassle for your customer to go to a competitor. And actually one of the best ones here is just the perception of risk that they think like, okay, we’re doing an operation, we have a heart valve, we buy the heart valve from this supplier. We could save some money because they just raised their prices 10%. We could go with another heart valve maker, but what if something goes wrong? You know, it’s just not worth it for 10% to take that risk. So perception of risk can be helpful. Uh, basically complications, anything, anything that’s complicated, that’s integrated with your company perceived as crucial, you can generally get away with a five to 10% increase, which is. you know, sort of the hallmark of a switching cost. But very few can get away with more than that. If you annoy your customers too much, eventually they boogie, and that’s that. Okay, so that brings us back to DD. Now what is the, you know, what’s the story with DD? I mean, we’re not gonna do sort of a case here. I mean, I’m just gonna tell you my take. But when I look at DD, what I see is from the consumer side, I see a commodity service without much power. You can’t get your customers to love you, you can’t get your customers to spend all day looking at your app. It’s a utility, it’s a standardized service, all they really care about is the price and how long they have to wait. That’s just the business you’re in. There’s nothing wrong with that. People who sell coffee cups are like this. You know, you sell coffee cups, that’s what you do. You can’t get your customers to care. People who sell bottled water, consumers don’t care. There’s not enough psychology going on there. You just don’t have a lot going on there. Okay, fine. Where I think DD gets really interesting is on the driver’s side, because it’s a multi-sided platform, and the other user group, suddenly there’s a lot you can do. Because it turns out drivers are not just coming there to make $5 today. It’s not a transient interaction. They’re coming there to build a career in many cases. Your best drivers, the best 20% that you want, you’re offering them a career path. You’re offering them the ability to build their own small business. You’re offering them stability and flexibility in their life such that if they just had a new child and they don’t want to work in the office and they want to work five hours a day to take care of their child. you can offer that. There’s a lot of psychology. And there’s a lot of switching costs you can build. And I think that’s what DD is doing. I think they are building in switching costs very aggressively for the top 20% of their drivers. They’re offering them financing. And this is that this new company they’ve built, which is it started out as all their driver services, all their driver services, everything that’s on the drivers app for DD, the discount on gasoline. the discount on maintenance, they have maps of auto shops all over China, the DT drivers can go to any of them and get discounts because they negotiate as a group. There are government services, they even have a bathroom map, you can get bathrooms anywhere you want in China. Maybe in Mexico they start offering insurance to people’s families because that was very important to the drivers. They help you buy the car, but they only offer that to the best drivers and then you have a financing relationship with them for over years. There’s lots of ways you can build in switching costs where that driver’s not gonna bounce back and forth and say I’m out of here, I’m going to lift, whatever, get lost. Now there’s a lot you can do in terms of psychology and especially in terms of switching costs on the driver’s side. And the services that DD has built about a year and a half ago, they made this announcement, it got no press. But they basically said our driver services, we are gonna spin that out into an entirely new business, which we call Xiaoju Driver Services, Owner Services. And it’s no longer gonna be just for the tens of millions of Didi drivers in China, it’s gonna be available to anyone who owns a car in China. They’re basically turning that into a new business, like a new platform business model that connects all the car owners of China. with all the services those car owners might need, from maintenance to auto repair, to new tires, to supplies, to bathrooms, to whatever, to insurance, all of that. They’re spinning out a new platform model the same way Alipay began as a payment service and became Ant Financial, an entirely new platform. That’s what’s happening on the driver’s side, which is really, I think, interesting on lots of levels. So my take, I’ve been talking at you for a while, so I’ll give you my last. 30 seconds. What do I think of DD and really Uber as well? I think DD and Uber were both first movers and that’s a very powerful move. I think based on being a first mover, they were able to put in a platform business model which has good strengths, regardless of whether they have a network effect. That’s great. First mover, awesome. Platform business model, awesome. The network effect people talk about, I don’t think it’s terribly compelling. I think it’s fine. I think it’s an advantage. I don’t think it’s a massive hurdle. I think they have outspent their competitors on marketing and IT costs. I think that’s a good move. Generally, if you’re bigger, you can spend more on IT. You can spend more on marketing than a smaller. That’s a good economies of scale advantage. But I think long-term, their biggest strengths are gonna be. We have a platform business model, we have big market share, and we’ve built in serious driver switching costs that get us the best 20 to 30% of drivers. You can have the churn. Try and build your business against the churn. That’s what I think. And that’s all great. I would characterize that as a very strong competitive position in a market that’s gonna let them dominate. However, and this is my last point. Just because you dominate doesn’t mean you make money. Dominating is required to make money. It’s not a guarantee that you make money because the economics are still unclear. It may turn out, yes, you dominate a business that’s not terribly profitable. The people who own vending machines, you can dominate the vending machine business, doesn’t make you a billionaire. The fact that there are low cost substitutes available for so much of this, I think is gonna… seriously constrain their profitability long term. But you know what, you don’t get everything in life. You don’t, not everyone gets to be Alibaba. You don’t get dominant, you know, you don’t get a dominant market position plus unbelievably attractive economics at the same time. Sometimes you just get one or the other, and you know, take what you can get. So they’ve got a very good hand. It ain’t an Alibaba hand yet, it could be. but we’ll have to see how the economics play out over time. But you got the dominant market position and that’s pretty amazing in its own right. So, you gotta have the glass half full viewpoint here. It’s an amazing business model, it really is. But maybe it doesn’t make you Alipay, doesn’t make you Ant Financial, doesn’t make you Tencent. Still pretty awesome, you know, still pretty, you know, still an amazing business. Okay, so that’s kind of my take on all of this. And I’m gonna put this up under learning goal number 15, which is the basics of DD and switching costs. What I like to do with these classes is give you an important idea that you should remember. Switching costs and marketplaces for services, you know, these are in the top 30 ideas you have to know. This is in your. your toolkit. An easy way to remember a big important idea is to pair it with a company or a person. So I’ve paired it with DD. When you hear DD, think switching costs. Think platform, marketplace services. You know, just sync those. two ideas with this company in your brain and it’ll be a lot easier to remember. I do this all the time. I always pair the important ideas with a person. Makes it easier to remember. So that’s kind of the takeaway for today. That’s Learning Goal 15, the basics of DD and switching costs, the two main ideas, switching costs and marketplace platforms for services, not products. And that’s it. I hope everyone is doing well. It is, you know, for those of you following life in Thailand, everything shut down. I mean, everything has shut down in the last week. The borders are closed. The airlines are stopped. And most of the stores are closed. And most of the foreigners, like myself, we are here on either non-immigrant or tourist visas, which means we are mandated to leave the country every 30 or 90 days, depending what situation you’re in. Nobody knows how to do this because you can’t cross the border. The borders are closed. You can’t fly out of the country. There’s no flights. And if you do manage to get out, you can’t get back in. So the embassies are all fortunately flying into action right now. The US embassy, God bless them, has jumped into action and is helping people out. So, you know, God bless. But, you know, worst case scenario, I’ll fly to a beach in a week or two. I’ve got actually a month or so before I have a problem with my visa. But yeah, we’ll see what’s what. But it’s crazy. You know, and it’s, we’ll see what’s happening. But pretty amazing. And I’ve been talking with my family who are in California. And unfortunately, my parents are both seniors. So this is, you know, this is a serious concern for seniors, no doubt about it. I’m, my dad is one of these guys. My dad is kind of an old school John Wayne type guy. Like he doesn’t take anything seriously. Like this guy wouldn’t wear his seatbelt for decades. Like he wouldn’t do it. You know, he’s got that sort of John Wayne, I don’t care. And I’m sort of impressing on him, like, look, this, you gotta take this one seriously. You know, this is, and here’s my little trick. A lot of my friends and business partners are doctors. And because I’m his son, he doesn’t listen to me, you know, because I’m, and to be fair, I don’t listen to him either, so it goes both ways. But I have my doctor friends call him and like basically say, look, We’re in the ER, this is what we’re seeing today. Wear a mask. And that actually works because he listens to doctors who call him from the ER. So I’ve been, that’s my standard go-to solution when he doesn’t listen is I have a doctor call him. And that seems to work. So I’m gonna have sort of my business partner call him who is currently in charge of several emergency rooms in South Carolina. And he went from a week ago. We’ve started to see some coronavirus cases showing up in the ER too. The whole ER is full of cases and I’ve put three people on ventilators in the last three to four hours. That’s what’s going on in his ERs. So it’s for seniors like my parents, I’m trying to get them to panic a little bit, not irrationally but a little bit. And we’ll see. If they’re not going to mask up, then just please stay home and watch TV. Anyways, so that’s a little worrisome, but apart from that, you know, I’ve been telling my friends like take it easy. Don’t worry too much. If you’re not a senior, you know, you’re probably okay, including myself. So it’s an interesting balance of panic and don’t freak out, you know, it’s hard to deliver both those messages at the same time. But anyways, that’s been the week. It’s been pretty crazy. I hope everyone’s doing well. I hope everyone’s taking care of themselves and it’s probably worth being a little overly worried. just as a matter of, let’s just worry more than we probably need to. That’s probably not a bad posture for right now, given the next couple weeks. Anyways, that’s it. Sorry to leave on a dour note, but that’s kind of what I’ve been thinking about all day. But apart from that, everyone take care, stay safe, and I will talk to you next week.