In the past month, two Chinese ecommerce companies focused on on-demand grocery ecommerce have announced they reached operating profitability in 2022.

The two companies are Freshippo (i.e., Alibaba) and Dingdong (i.e., Maicai), both of which I have written about previously. They are both innovative business models focused one of the last subsectors for ecommerce, which is groceries. Groceries is the ecommerce subsector that giants like Amazon and Alibaba have avoided for almost twenty years.

So had did they both reach profitability in 2022? I didn’t see that coming. In fact, I was pretty bearish about Dingdong, despite liking the CEO and Founder Changlin Liang.

It’s a really interesting question:

- Ecommerce in groceries is notoriously difficult and chronically unprofitable. Has it finally become a good business?

First some background.

Why is Ecommerce in Groceries so Difficult?

As mentioned, the ecommerce have avoided this sector forever. They did books, electronics, appliances and so on. But stayed away from groceries. Why?

- Perishable goods. You can’t keep groceries in the supply chain or inventory very long. There is a lot of spoilage. And you often have to time the goods in the supply chain be ripe when people order them.

- Fewer SKUs overall.

- Small margins on mostly commodity products. Think selling apples and milk. It’s hard to digitally disrupt a sector if the profits are 3-5% (typical for supermarkets).

- Fast, frequent deliveries required. People shop for food several times per week. So, delivery costs are a big problem. Especially when most deliveries are customized packages of low value, heavy items with lots of different SKUs.

- Consumers like to buy groceries in person. Consumers like to check the fruit in person. They like to wander the aisles with their list.

It’s just a lot more difficult than selling books and apparel. But two business models were pioneered in China to solve this problem.

- Alibaba opened its Freshippo supermarkets and also started acquiring and digitizing others. Their approach, which I have written a lot about is, is to combine ecommerce with physical locations. This solved most all of these problems.

- Freshippo retail outlets are retail space plus local services plus a logistics hub with on-demand delivery. JD built a somewhat similar model by partnering with Walmart.

- This is the new retail (online-merge-offline) Alibaba talks so much about. They call it a new retail paradigm, but I think it mostly started as a solution to ecommerce for groceries.

- In contrast, Dingdong pioneered a purely online business model. It’s a mobile app that does on-demand delivery of groceries and other fresh perishables. It accomplishes this with a network of small warehouses in local neighborhoods and close to customers. It basically built a specialized system for groceries that connects suppliers, front-end warehouses and delivery riders. This is similar to the Ze Delivery model for beverages in Brazil.

The problem with both of these models was they were unprofitable for many years. I figured Freshippo could operate as part of the larger Alibaba ecosystem, but I was not optimistic about Dingdong’s business model. We also have ecommerce groceries models at Meituan, JD, Pinduoduo and Miss Fresh in China. As far as I know, all of them are losing quite a lot of money.

The Dingdong / Maicai Model for Ecommerce in Groceries

Softbank-backed Dingdong (like Tencent-backed Missfresh) was founded in 2017 to:

- To solve the difficulties of selling high frequency perishable and difficult to transport groceries online.

- To tackle some of the pain points for both Chinese families and farmers.

- To capture a potentially massive opportunity in groceries.

It was a specialty ecommerce play, which are business models I always look at.

Dingdong argued that groceries are unique ecommerce markets where a specialty approach is viable. The argument is:

- A specialized model is superior for meeting unique customer needs. Dingdong was trying to differentiate for consumers based on:

- Product quality (better groceries)

- Faster delivery (under 30 minutes)

- Attractive prices

- Greater product variety (12,500 SKUs)

- A specialized model benefits from specialized logistics systems. Dingdong has a “frontline fulfilment grid model” with regional processing centers connecting with local fulfilment stations. Then contract delivery people do the last mile. It also has direct connections with suppliers (75% of its SKUs were direct sourced), specialized facilities and lots of cold chain capacity and trucks. The argument is the D2C specialized model gives the company end-to-end quality and cost control. It can also work directly with suppliers on standards and on demand projections. By 2021, it had 1,600 3rd party suppliers, most on 1-year terms.

By the time Dingdong went public in 2021, it was doing deliveries in 29 cities with 6.9M monthly transacting users. And it had a highly scalable business model. They were expanding rapidly by cities.

Founder and CEO Changlin Liang was actually very clear about what he was doing. The SEC filings are well written. Here is the business model from their IPO filing.

Note the focus on high frequency purchases. And that leads to scale and high density of orders in small areas. Then they have higher quality, faster delivery, and greater product variety. In theory, this should lead to increased spending per user over time.

Here is how they described their strategy in their IPO filing.

Note how they planned to drive user growth and increase user engagement.

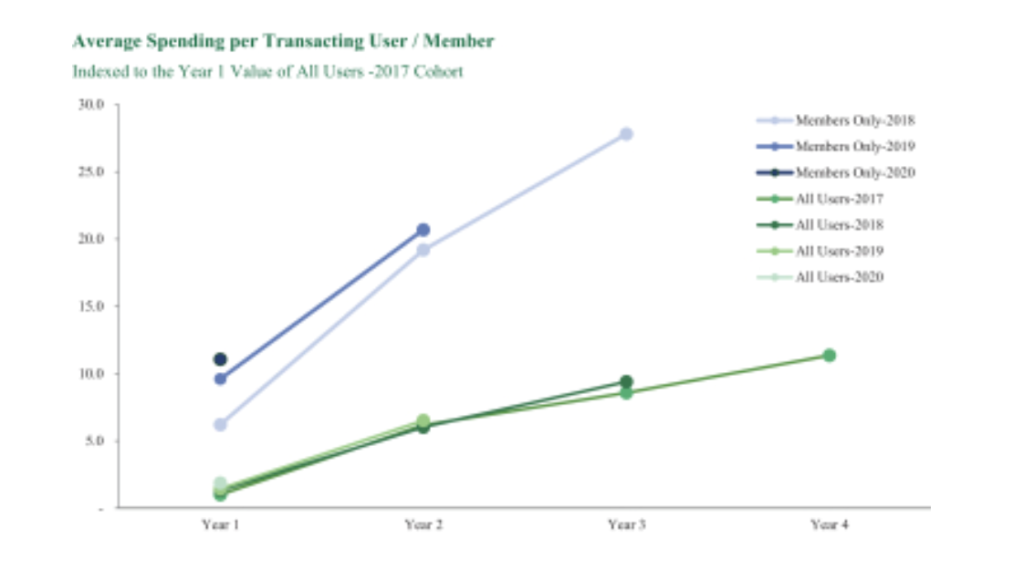

And they said cohorts were increasing their spending over time.

Then they use that strong position on the consumer side to go for scale and efficiency on the supply-side.

That’s all good. And they were executing on it.

The problem was the business model wasn’t profitable. It wasn’t even close.

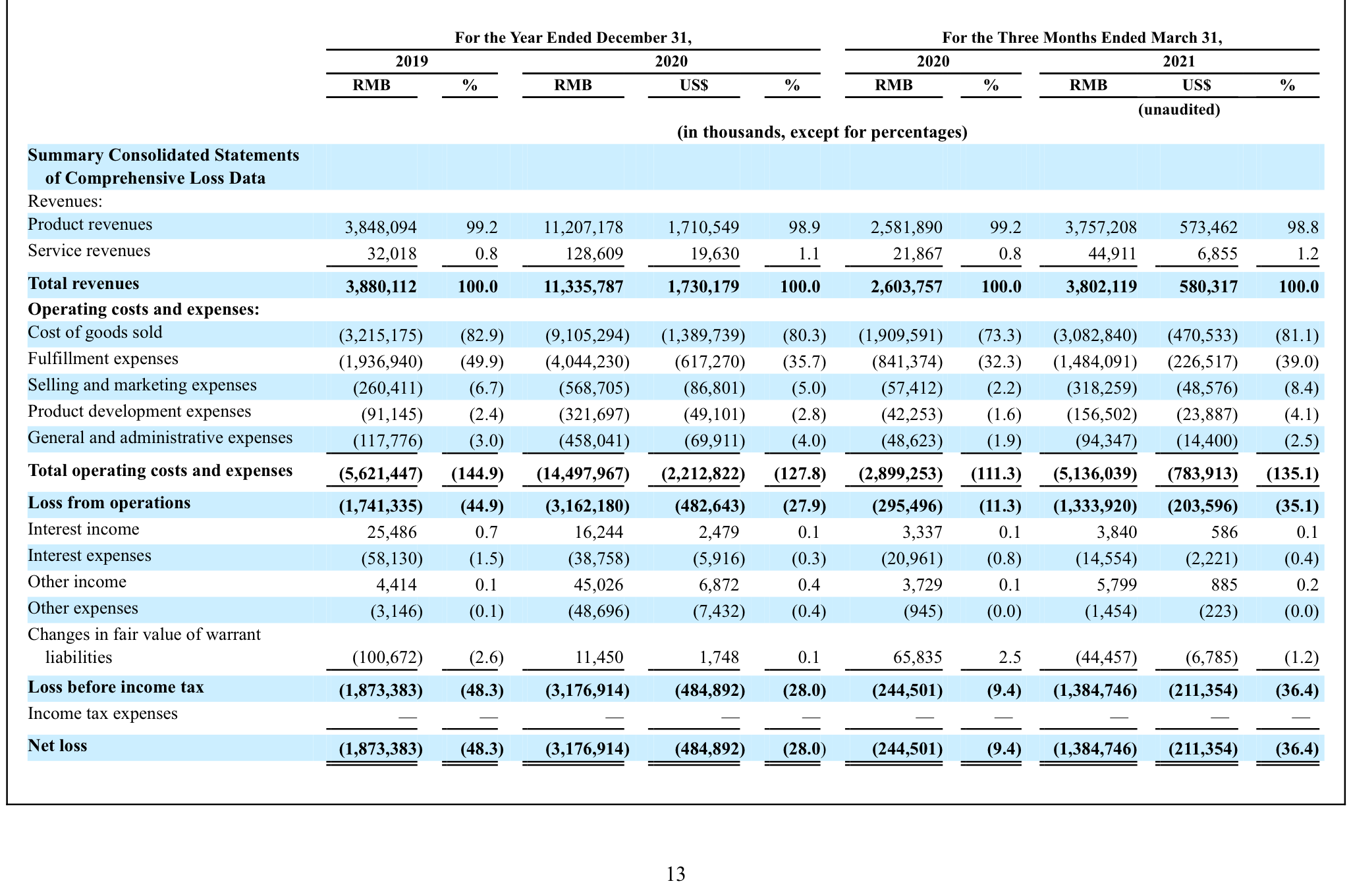

Take a look at the financials for 2020 and early 2021. They were on track to earn $2.3B in 2021 and lose about $800M. They had gross profits of about 20% of revenue. And then fulfilment costs of about 40% of revenue. That puts them at -20% on operating profits before you even start adding in marketing and other expenses.

Back in 2022, I argued this business model was problematic. It’s not clear they could get to operating profits. Let alone significant operating profits. I argued they would have to:

- Go for greater geographic density in a few cities. Go after the fulfilment costs by having greater orders per local area and then doing batching and data-driven routing and fulfilment.

- Get bigger so they had more purchasing power. Try to drop the COGS.

- Expand their products to get more revenue, especially branded and private label products (lower COGS and higher gross profits).

- Try to focus on something Alibaba and the other ecommerce giants don’t care about. Avoid direct competition. There was just too much competition in this space.

And that was where I left it a year ago.

So, you can imagine my surprise when I heard their announcement at the end of Q4 2022.

That’s in Part 2 (coming tonight).

-jeff

–—–

Related articles:

- How Alibaba Freshippo and Dingdong Got to Profitability in Ecommerce Groceries (2 of 2) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- Dingdong vs. Oriental Trading: How to Spot the Specialty Ecommerce Winners (1 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Can Dingdong Win in Groceries and Specialty Ecommerce? (Asia Tech Strategy – Podcast 90)

- How AB InBev and Zé Delivery Are Changing Ecommerce in Beverages (Tech Strategy – Podcast 139)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Specialty Ecommerce

- Geographic Density

- Grocery

- Retail

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Dingdong

- Alibaba Freshippo

———

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.