Correction: I had Michael Jacobides’ name incorrect throughout this episode. My apologies. Podcasting while sick may not have been my best idea.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

The slides mentioned are below.

Related podcasts and articles:

- #30: Ecosystems vs. Platforms

Concepts for this class.

- Ecosystems vs. Digital Platforms

- SMILE Marathon: Ecosystem Orchestration and Management

Companies for this class:

- Alibaba

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

—–transcription below

:

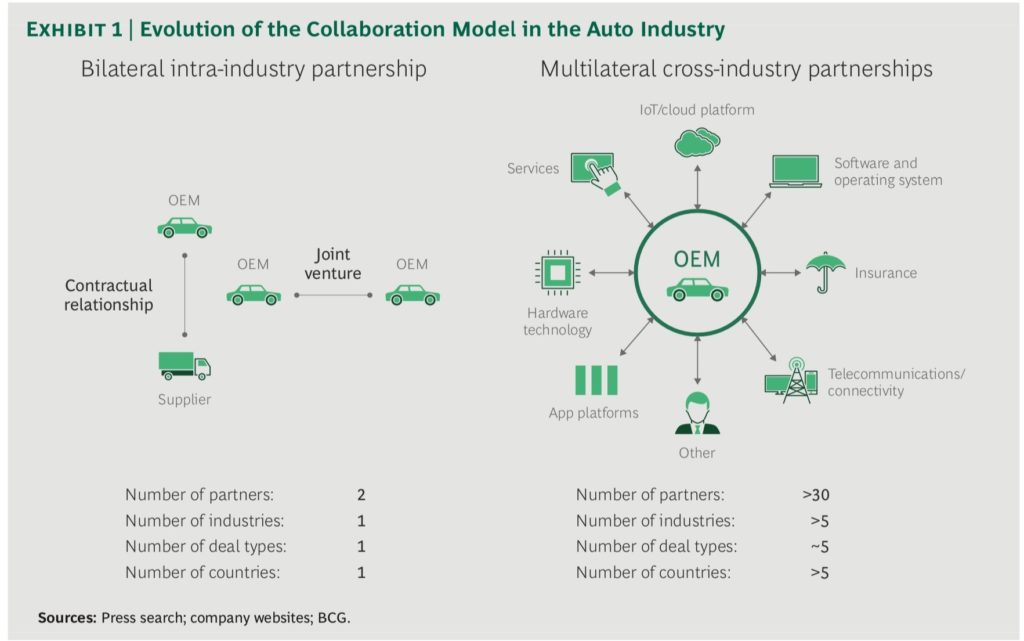

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy podcast and the topic for today Forget about this term ecosystem the Alibaba ecosystem Instead think about new collaboration based industries and business models So today’s talk I guess it’s a bit more of a rant than is normal for me, but I think there’s a lot of fuzzy thinking, a lot of fuzzy terminology around this idea of an ecosystem or a, you know, Alibaba’s economy, or digital economy and things like this. It’s not really helpful language. In trying to tease out what we’re really talking about, there’s a lot of very smart people sort of thinking about this right now, and the thinking’s getting better. So I’m going to summarize what I think is actually some very good, clear language and thinking in this space. But I don’t have the answer. I don’t think anyone does and I’m going to sort of, I don’t know, try and take it a couple steps further. So the idea is collaboration. That’s really the best word I think for all of this collaboration between various businesses, partners who have traditionally not been business partners and have not interacted in so many ways. And this could be within an industry or it could be across multiple industries. it could be across multiple geographies. But we’re seeing a sort of more collaboration-based business model emerging. And sometimes we’re seeing entire industries based this way. And I think that’s probably the best first word to think of is collaboration, new combinations, new partnerships, things like that. So I’m going to go in to sort of tease out some of that. And a lot of the thinking here is coming from three people. It’s Peter Williamson, who is a professor and old colleague at Cambridge University, who was actually the first, pretty much the first person who got me into the whole professor thing many, many years ago. And Peter Jakovitson, I’m probably saying his name wrong. I’m gonna put their names in the show notes, who thinks about ecosystem strategy and management. And then Boston Consulting Group, which has some fairly good thinking on this as well. So I’m gonna summarize a lot of their thinking. I’ll try and point out. that this is their thinking. Some of it’s mine, but a lot of it’s theirs, and I don’t want to take credit for that, obviously. So let me get into this, but first a bit of a qualifier. I am traveling. I’m down here in Phuket for a couple of days, so I’m using a travel microphone and such. So I’m going to try and clean up the audio. May not be sort of up to normal par, so sorry about that. We’ll see how it goes. Second, this is going to be a little bit shorter than normal. I’m kind of under the weather. This is why it This week’s podcast is a day late. I was kind of sick with a migraine, so I’m a bit out of it. I’m going to be a little shorter than normal, but maybe that’ll be improvement. Maybe I should be a little more concise and focused in these. And for those of you who are subscribers, this is all going to go under learning goal 30, which is ecosystems versus platforms. And the two main concepts for today are ecosystems versus digital platforms, which is a repeat there. and the Smile Marathon. And one of the key dimensions in the Smile Marathon is ecosystem orchestration and management. Now, one of the things I’ve gotten in feedback from a lot of people is it’s easy to get lost in the content. So when I say, hey, this is about learning goal 30 in ecosystems versus platforms, people having a hard time keeping that together and sort of clear in their head. So I also have for you today. in the show notes, a simple graphic, which I think captures all of the sort of theory that I’ve talked about. I’ve actually put two slides. One is a pyramid with lots of colors, which this captures sort of all the concepts. And then a second slide, which is just companies, and it’s just a running picture of all the various logos of companies. we’re covering. So this is going to get updated into the web page. And you should be able to just click on this in the future, whatever concept we’re talking about. And it’ll pull down all the content by each of those topics. And it all sort of puts it together. So I’m going to take a couple minutes and just walk you through it. Now, if you look at the pyramid, what you can see is start on the left and the right. The left and the right are just lists. So on the left, we have digital concepts. These don’t all fit together beautifully in some sort of grand unified theory. It’s just a list of the 20, 30, 40 most important ideas within digital. And I’ve just laid them out. So digital platforms. And I’ve actually put this into a couple sections, one, two, and three, because I’ve talked about multiple types of platforms, payment, audience builders, things like that. Digital economics, there’s a lot within there. Digital superpowers, scalability, network effects, things like this. And that’s just a drop-down menu. And anything we talk about, you can just click on there and pull up the information from that. Underneath that, I have sort of new digital tools and use cases. Now, this is kind of the ongoing. Every month, someone thinks up something new. Here’s a GPS that we’re using in smartphones for our bank tellers. Someone takes a new digital tool like GPS and finds a new use case for it in an industry, like let’s give that to bank tellers, and therefore we can do this. And there’s a constant stream of these new digital tools coming out all the time, IoT, AI, machine learning, GPS, this feature, that feature, photo sharing, whatever. And industry after industry, they keep finding creative ways to apply that in lots and lots of use cases. So there’s just a constant stream of those. And as this sort of happens, you have to kind of make the call, how important is this? Is this transformative to my business? Am I in trouble? Or is this not a big deal? It’s just a natural tech upgrade, which happens all the time. So on the left, laundry list. Lots of stuff. It’s all going to be categorized there. You should be able to click on any of these, pull up what you want. On the right side of the pyramid, we have companies, and we have tech trends. companies, obviously we cover a lot of companies, Alibaba, Tencent, whatever, it’s just gonna be a list. You can click on any of those, and if you’re more interested in company level analysis, then you can pull up all the thinking, writing, podcast videos, everything on say, I don’t know, Meituan. I have sort of broken those into two buckets, which I call sort of the Asia-China digital giants, and then rising companies. These are smaller companies that I think are important that are maybe not so much on the radar. Anyways, those will all be there, nice and simple. And below that, Asia tech trends. These are sort of larger scale phenomenon that I think are important, like new retail, online merge offline, new manufacturing, smart devices, logistics, social media, digital marketing. Now these are much bigger than any particular digital economics idea. or any particular tool or use case. These are sort of sweeping trends that I think are going to play out over many, many years. So those you can click on those, pull them up, fine. Those four buckets, digital concepts, new digital tools and use cases, companies, Asia Tech trends, all the content’s going to be sort of in there. However, what does all this mean? I mean, how do you view this? And then we get to the pyramid in the center with lots of colors. And this was actually, I threw this sort of question out to people, and a nice woman in Thailand came up with a version of this that really, I think, crystallized a lot of what we’re talking about. So thank you for that. I appreciate the feedback. Very helpful. Which is this idea of, look, if we’re talking about strategy, it’s a lot about what decisions do we have to make as a CEO, an executive. How attractive is this business? Is this a very difficult business where you’re constantly fighting and you never have any advantages? Is this a business you can win? And generally, you wanna move up the pyramid. The bottom of the pyramid, life is very, very difficult. You need good management, you have to fight every day, and even then, your odds of success are very low. As you move up the pyramid, life gets a lot easier. You make more money, it’s generally easier. So I’ll sort of take you through it. At the bottom level of the pyramid, I’ve put things that are sort of short-term tactics. This is using money as a weapon. Let’s take our bank balance and just spend a lot on marketing and try and bury our competitor. That happens all the time. Maybe we’re using venture capital money, so money wars, blitz scaling. last man scanning. We can call this like resource-based competition. We can talk about irrational competition that sometimes people do stuff that will never work in the long term but they’re just doing it irrationally in the short term and you have to respond. Dirty tricks, scams, that stuff is pretty common. So short-term tactics is kind of the bottom of the pyramid. You have to know how to deal with this stuff. You move up to the next level. This is more the marathon. This is the operational decisions you have to make day after day, regardless of whatever your business model is. You’re running a restaurant. You’ve got to choose the menu. You’ve got to refurbish the outlets. You’ve got to optimize your supply chain. You have to improve your marketing. You have to hire and train your staff. You’re in this game of just constantly running every day, i.e. a marathon. And a lot of business. these days is just about speed. You just have to be fast. But you can’t be fast at everything. That’s ridiculous. You can’t just tell everyone, do everything faster. No, it’s not viable. You have to decide what marathon you are running. And this race never ends. You never win, you just run, run, run, every day, every month, every year. You run and you run and you try and pull ahead of the pack of other runners. and hopefully get a little space between you and them. But you can’t do everything faster. There’s this argument that speed is the new scale. That just makes you kind of frantic. You have to choose what race you’re running. And I’ve given you 12345, which the acronym is SMILE. So I call it the SMILE Marathon. That’s the yellow band. And I’ve gone through this before, scale, scope, effectiveness, and efficiency, machine learning, sustained innovation, rate of learning, ecosystem, orchestration, and management, which is one of the key topics for today. You run, run, run. Now, as you run, you can also start to get structural advantages to your business after a while. Sometimes you can get them early. Sometimes they can emerge later. Those are competitive barriers. Those are competitive advantages. and I’ve put those in green. However, as I’ve mentioned several times, there are sort of two aspects to this. The first, which I put in darker green, which is higher up the pyramid, is this is when you have sort of a structural advantage over time where, look, you just can’t match the cost structure of my factory because I’m bigger than your factory, so my unit costs are lower. You can get into my business, there’s no hard barrier to jumping in here. But if you get in here, I’m going to grind you into the ground because I have a structural cost advantage. We’d call that either a production cost side advantage or economies of scale or scope. And you can get various ones of these, but this is more about being in the business. You’re just hard to compete with long term. And I’ve put five or six of these, and I’ll go into a lot of detail. A different version, which I’ve put in lighter green, is more of an entry barrier. It’s not that you can’t, it’s not that like you can’t get into my business, it’s just a little bit difficult. If you want to compete with me in railroads, you’re going to actually have to get the land and lay the tracks and build a regional or national railroad network and that turns out one, it’s expensive and it’s pretty hard to do because you can’t get the land. That’s more of an entry barrier. Most entry barriers you can overcome with money. So it’s not as strong as a structural advantage, like a competitive advantage, but it is sort of a some degree of a blockage. And I’ve put in various types there. And I consider this more of a soft advantage. And there’s other types of soft advantages, like chicken and the egg, bundling, and other things. Now ideally, you want both. You want an entry barrier, and you want a more harder competitive advantage, I don’t know, a mobile network like your China Unicom or China Mobile or Vodafone. There’s a very big entry barrier where you have to create a whole nationwide network of base stations so you can have your service available everywhere. That’s very difficult. You have to get the licensing. You have to license the spectrum, which is difficult. You have to auction for that probably. Then it costs a lot of money. So there’s a big entry barrier in terms cost and difficulty. And then when you get in, if you want to pay that price, then you’ve got to compete with an incumbent who has network effects, economies of scale, and other more powerful competitive advantages. They have both. Coca-Cola doesn’t really have an entry barrier. Anyone can start a soda company, but they got powerful competitive advantages. And some businesses just have the entry barrier and not the competitive advantage. OK, there’s a lot in there. But generally speaking, as you move up the pyramid, into this area of structural advantages, life gets a lot easier. You’re no longer competing with a thousand restaurants or other types of companies, you’re competing with three companies. You’re a mobile teleco company, you have two competitors in your region. Now they can still be brutal to each other, but structurally it’s not as many players. And then at the very top of the pyramid we have winner take all. This is when you have built so many advantages, you’re basically unmatched. Nobody can compete with you. Life is good, you’ve got the whole market, you’re probably making a ton of money. That’s like the NBA. The NBA doesn’t really compete with anybody. Not really. People who love basketball love basketball. And they don’t have any serious competition anywhere. Now it doesn’t mean you’re going to be winner take all in the whole world, it’s usually within a niche. But you can get to that level. Facebook is there. Google is there. Tencent is there. Alibaba is, well, I mean, e-commerce is actually kind of competitive. But within there, you can have sort of dominance, or you can have what we’re going to talk about today, which is ecosystems, complementary platforms, linked businesses. There’s a lot of versions of that sort of regional or niche dominance. And I think ecosystems is one of them. And that’s basically my pyramid. You want to move up the pyramid. Now, across the base of the pyramid, I put three buckets. On the far left, I’ve put traditional businesses, pipelines, traditional products and services. I’ve talked about that a lot. On the far right, I put platforms as a different type of business model. And then in the middle, I put this idea of ecosystems and conglomerates. So it’s sort of like you can be trying to build one of three business models. And you can play on any side of the pyramid, but generally you want to move upwards. And life is a little better in the center, but not as many players. OK, that is the basics of the pyramid. So today, to repeat, the learning goals, this is all under learning goal 30, ecosystems versus platforms. But the two key ideas are ecosystems versus digital platforms. So we’re talking about the center of the pyramid. and specifically at the top of the pyramid, where there tend to be some ecosystem players like Alibaba. And then we’re also talking about the Smile Marathon. And the dimension we’re talking about is ecosystem orchestration and management. So that’s in the yellow band. So that’s where these two ideas for today would sit in what I’m calling the Uber chart, because it has everything. Hopefully that is helpful. I think it captures everything. And we’ll just keep talking about various spots within the chart and that’ll be how we’ll do it. Anyways, if you have any feedback on this, let me know, we’ll keep updating and editing. But I think, hopefully that’s a lot better. Okay, with that, let’s get into the content. Now, it hasn’t escaped my attention that I’ve just used the word ecosystem many times, even though the title of this podcast is Forget Ecosystems. I’m gonna use that language for now and I’m gonna try and… pull it down to something more granular and specific. But I mean, I talked a lot about pipelines, traditional businesses, and how they go to platforms, which I’ve sort of described as a simplistic version of an ecosystem. It’s a network-based business model that’s kind of a simple version of an ecosystem. OK, what’s the difference? The way I think about. what we’re calling ecosystems, is a new type of business model or a new type of industry structure that’s based fundamentally on collaboration and new combinations. For example, it’s not one company making a product and sending it out to the world, like a traditional business like a pipeline. And it’s not a company like, let’s say, Facebook or Amazon or Didi or Uber. where you’re enabling an interaction between, say, a driver and a rider. That is definitely doing a collaboration, an interaction, but it’s a very simple, narrow type of transaction. These companies are not doing 50 different types of interactions or collaborations. They’re just doing one or two. I sell, you buy. I drive, you ride. So let’s think of a little more complicated one. And this is an example from Peter Jacobison, which is these Nestle Nespresso pods. When you buy these machines for your house, you then buy the little pods, those little plastic capsule like things. You pop it in the machine. It does sort of a single serving. Then you get a cup of coffee. OK, that’s a type. He describes this as a sort of simple type of ecosystem business model. Because the company that led this, the orchestrator of the ecosystem, was Nestle. Now Nestle doesn’t make machines. They make coffee. They have some simple products, but they’re definitely not in the machine making business. But in this case, they worked, they sort of reached out to various machine builders to make all of these various gadgets you put in your home, and then they supply the pod. So it was. The important aspect there is they reached outside of their traditional industry. And this, I think, is one of the key dimensions, is you’re doing a collaboration. You’re working with others. Are you working with other companies, let’s say, within your traditional industry? Are you reaching out into an unrelated industry, cross-industry collaborations? That’s what’s different in this. They worked out to people that make machines. then you can buy them all in the store, buy the pods. And in this case, Nestle would be the orchestrator, the one in charge, the one leading, really by virtue of the fact that they controlled the patents for the pods. So no one was allowed to make these pods or the interface, I think the machine interface with the pod, without their permission. So by virtue of their brand, we’re a big coffee company, and we have the patents. they were able to sort of create this very simple ecosystem between coffee and machine manufacturers to sell all these things. OK, simple version. Now, I’m putting in the notes a slide. This is from Boston Consulting Group, which I think is outstanding, about the auto industry traditionally, because they’re sort of an ecosystem-based business versus what’s emerging in auto, which is facing major disruption from autonomous vehicles, electric vehicles, ride sharing, everything Elon Musk is doing. Now on the left, you see that they describe a traditional partnership, which would be, let’s say, a simple ecosystem. Within auto would be. relationship between the automaker, the OEM, and the suppliers. Obviously this is going on. The people that make engines collaborate with the car maker. The people who make wheels collaborate. There’s a lot of sort of contractual relationships between the OEM and the supplier that’s been going on for a hundred years. And you might also see joint ventures between two different OEMs, Toyota and Honda, Toyota and Ford. Maybe they’ll collaborate on common who knows what, standards, electronics, spare parts, because there are some benefits there. So BCG described this as a bilateral intra-industry partnership. So yes, there’s a partnership. Yes, there’s collaboration, which is the key word of this talk, collaboration. But it’s happening within an industry. And it’s happening sort of just bilaterally, very simple. Not that many partners, not that many types of interactions. You can see sort of automakers today. The OEMs are at the center of a vast array of collaborations. There are software makers. There are operating system makers. There are cloud platforms. There are IoT people. There are services companies. There’s hardware technology. There’s semiconductors. There’s app platforms. There’s suppliers. There’s 5G and telco. There’s insurance companies. you have a dramatic increase in the number of partners they’re collaborating with. And what’s important also is this is outside of their traditional industry. They’ve gone cross-industry. And the interactions, the collaborations are not bilateral. It’s not just the OEM dealing with their suppliers and the OEMs dealing with one other automaker. All of these parties are working together. There’s huge numbers of different interactions happening between all of them. So it’s. multilateral as opposed to bilateral. And that’s what they’ve put at the top of the slide, which is outstanding. Bilateral intra-industry partnerships are going to multilateral cross-industry partnerships. And I think then you look at how many partners they’ve got 30, 40, 50 partners. Tons of industries, tons of deal types, tons of countries. That is a good picture of a, what we’re calling an ecosystem, but which I think they more appropriately call a collaboration-based industry model. And that was kind of the topic for today, collaboration-based business models or collaboration-based industry structures. Now, in the tech industry, this is actually not terribly new. It’s definitely new for the auto industry. It’s not that new for the tech industry. There have long been these sort of industry-wide collaborations because it was necessary because tech all has to work with other tech. So one of the companies people point to when you talk ecosystems, well, they point to a couple types of companies, but one of them they point to is Armholding, which is the UK Cambridge based chip designer, IP library, very famous company. Peter Williamson, the professor at University of Cambridge Judge Business School, he writes about them. I think they’re, you know, in this, they’re in the same town, so it’s kind of easy. You know, that they really did create an ecosystem around chip design, where they work with the people who do the design, the manufacturing, the distribution, the foundries, the equipment for testing the chips, the equipment for design, all the people who make devices like your phone and your iPad and all of that, the app developers, the content providers. There’s a lot of people that collaborate within this space. very focused on what these chips can do and what they can’t. So that’s kind of a famous example of this. But we’ve seen that in technology for a long time. We’re just seeing it in a lot of other places. We never saw it before, like auto or coffee machines. So there’s a couple ideas here. It can get a little confusing. But why is it becoming more common? We’ve seen this in tech, but we didn’t see it the other places. But we’re seeing this more and more, this idea of either platform business models, which could be considered a simple ecosystem, increasingly connected companies, or at the broadest level, collaboration-based business models and industry structures. Well, it’s just the nature of going from the industrial to the information age. You know, we have Alibaba and Tencent. I mean, they are just very complicated companies with lots of platform business models that are all complimentary. They have linked businesses and they’re just getting so complex. It looks a lot more like a big business model with lots and lots of different partners who just collaborate and interact in lots and lots of ways that are getting harder and harder to track. One thing you see in the paper a lot recently is this whole idea of Epic Games versus Apple or Apple epic with their Unreal Engine, you know, they’re in eSports. They have game engines They’re increasingly fighting with Apple. That’s kind of two ecosystems fighting which we there aren’t a lot of examples of ecosystem versus ecosystem competition But we can see it in Alibaba versus Tencent. We can see it in Epic versus Apple And I think we’re going to see more and more of this because it’s becoming more common. And Peter Jakovitson and Williamson, they have very good arguments for why it’s becoming more common. So I’m going to summarize what they have said, which is one, it’s getting a lot easier to bundle things together than it used to be. Services, products, things are becoming more interconnected, more interoperable. So it’s easier to bundle them together and we’re starting to see more collaboration and interactions across the board. A lot of the things that people are building, especially when it comes to software, are modular. People are building things in blocks that can be added. So you can start to, one, they’re interoperable, and two, because things are modular, you can start to put them together in different combinations. Digital goods are just kind of easy to put together to begin with. We’re seeing questions and solutions that are increasingly beyond the ability of a single It is very difficult to offer ride sharing all across China if you’re one company. Now, Didi is not really one company. It’s one company orchestrating all the drivers and riders. It’s sort of a network-based approach. It’s getting very hard to do something like gaming if you’re just one software company. The things we’re offering to consumers and customers are getting more sophisticated, more robust, more complicated. And they’re increasingly beyond the ability of any one company to create. So you have to start to partner with others to offer a full solution. The world’s getting somewhat less predictable, a lot more uncertainty, things are happening faster. One of the benefits of an ecosystem is they can adapt much faster than a standalone company. It’s one of their strengths. This is something Peter Williamson talks a lot about because they can start to put together different combinations of assets and capabilities quickly against a changing environment. They’re very adaptable. As I’ve kind of talked about complements a lot, a lot of the value of anything you buy now is not just the product, it’s product plus its complements. I don’t just want the iPhone. I want the iPhone plus everything in the app store. Well, that’s a type of collaboration. If you’re going to have a lot of complements, you have to work with others. And more and more, as I sort of started with, competition is increasingly, or at least not increasingly, we’re seeing this phenomenon of ecosystem versus ecosystem. competition. Very complex and highly customizable product service bundles are competing with each other. It kind of makes your brain hurt to think about this. It’s like, you know, I’ve said this before, like traditional competitions like checkers, platform competitions like chess, this is like 3D chess. It may well be that the past, the industrial age, companies were based on scale, and fairly tightly run supply chains. The future may be an industry structure based on very complicated, interconnected, and collaborating companies. That may, in fact, be the future, and we’re just sort of transitioning there right now. Last point on this, why is this so important? It turns out ecosystem approaches are a very good response to disruption. when an industry like auto is just getting disrupted from four or five different angles. Like auto is super complicated if you’re a CEO. I mean, it’s going from sort of combustion based engines to electric. That’s one level of sort of disruption. It’s going from self-driving to autonomous. That’s another level. It’s going from car ownership to car ride sharing and mobility services. That’s another, they’re getting disrupted on three different dimensions. When you have that sort of uncertainty in your path, an ecosystem approach is a standard response to that. Let’s just put all the partners together. We’ll get 30 companies together, which is what DD has done. They have a DD auto alliance with like 30 companies. And they’re all working together as sort of an ecosystem approach so that they can adapt quickly. And they can draw on everyone else’s capabilities and competencies and create lots of solutions. It’s a very good response to disruption. So if you want to do this approach, what do you do? Well, you have to start thinking in terms of the ecosystem first, which is I can’t just create value for my customer myself. I have to create value for my customer and for everybody else, all my partners. I have to make it worth their while, because why would they be involved in this? So we have to sort of see beyond our own situation. A lot of value creation for others, but then within that value creation for everybody, I also want to capture some of the value for myself. And that’s a very interesting trade-off. That’s working for the public good versus my own private self-interest. And I have to balance those. Now, the public good, the reason, the big value that pays off here is co-innovation. That if I start to work with 10, 15 other companies, all who are probably outside of my own industry, they’re going to have skills. capabilities and competencies I don’t have at all and I probably can’t build. So I can start to draw on those and I can start to combine, all of us can start to combine previously unrelated things. So the ecosystem approach is very powerful in terms of innovation. But I also have to think about the interests of others. What are the motivations and interests of these other partners? How does it help them to join this? Nokia is kind of famous for starting a mobile operating system Symbian that never got anywhere because they never really helped others. They tried to take too much of the pie for themselves and it sort of died on the table. Steve Jobs even famously when he launched the iPhone he didn’t want other people to be able to create apps for the App Store and it was a very small number of apps when the iPhone launched and he had to be convinced to work with partners and let them build things for the App Store. And then it became a hit. So you want to think about roles, and then you have to be honest about what your role is. As soon as you say ecosystem, everyone wants to be the orchestrator. Everyone wants to be Apple. Everyone wants to be Arm or Epic. Okay, statistically, I’m not going to be the orchestrator. You’re not going to be the orchestrator. We are going to probably complementors or lesser partners. Very few people get to be the orchestrator. You shouldn’t plan a strategy about that. So you want to think about what are the, you know, what am I adding to my partners? What am I taking for myself? And what are the points of control within this ecosystem? And I’m assuming I’m not going to be in control. So then really the question for me is how can I be the most powerful complementor to this ecosystem that I don’t run? And that’s the key strategic question for most companies. If you do happen to get lucky enough to be the orchestrator, this is from Peter Jakovitson, you really have to decide the rules of participation and that’s really two questions. How much access is there gonna be? Is this gonna be an open ecosystem where anyone can join? That’s kind of my space. Is it gonna be managed? Is it gonna be totally closed, very tightly controlled? And if you make it more open you’re gonna get a lot more speed, a lot more adoption. you’re going to get a wider variety of capabilities and features you can draw on. But you’re also probably going to have quality problems. If you can think about, Didi had this problem, where Didi, a couple of years ago, had some issues with violence against passengers. And that was a question of openness. How easy is it to become a driver for Didi? And in response, they really tightened up their access. and had a lot more training and checks on drivers. So you need to think access is a question. There are pros and cons to both approaches. And then you’ve got to think about exclusivity and attachment. OK, if you do join this ecosystem, can you be in other ecosystems? If you’re a driver on Didi, can you also be a driver on Uber? This is actually kind of an issue in China this week where the government has just released an anti-monopoly law. which is very powerful. I mean, this is a big deal. And it appears to be mostly targeted at, effectively, the ecosystem players of China. Alibaba 10 cent these giants. And one of the issues they talk about, or at least is mentioned in the draft of the law at this point, is exclusivity. That if you’re a big retailer like a JD or an Alibaba, you can’t demand that a supplier, a merchant, I don’t know, Gucci, Prada, be exclusive to you. And that has kind of been happening a little bit. It has been frowned on, but it tends to happen anyways. So these platforms can’t demand exclusivity, but sometimes exclusivity is a good thing. So there’s trade-offs there. So you’ve got to think about access and this exclusivity question. Then you set up sort of the governance of your platform, and you have to think about this question of individual versus collective benefit. How do we help? ecosystem grow, which means we have to focus on the public good, but we also want to make sure everybody gets their own interests met. That’s a pretty big question. Twitter has historically had this problem because a lot of the innovations that happened on Twitter, which are not many, came from complements, came from people working on Twitter writing code for Twitter, and that’s where a lot of the best features came from. And then Twitter changed the rules and effectively kicked everyone out. these developers and nobody has forgotten that. If they were to open up and say please come to development apps for Twitter, people would be very distrusting. So that’s the individual versus collective benefit question. All right, let me make one or two last points and then I’ll call it a podcast because this is kind of a bit of theory. Peter Williamson has really taken a crack at this question of competition between ecosystems. And he has a book that came out recently called Ecosystem Edge. It’s pretty interesting. I think he’s, I mean, we haven’t quite figured this out. I don’t think anyone’s really cracked this thing. But I think he’s definitely started to effectively describe some of the competitive dynamics within it. And he basically, I’m just going to summarize what he said, rather than me, you know, paraphrasing. This is my notes from when I was reading his book. And his book is called Ecosystem Edge, which is what is the edge you get if you operate like an ecosystem. I would have used the word advantage, but he used the word edge because it probably sounds good with ecosystem edge. But he argues this is about bringing capabilities together. I use the word collaboration-based business models, but that’s not the term he uses. BCG uses that term. But he says, look, this is about bringing capabilities together that can be useful. It can show what’s possible. And sometimes it is just absolutely necessary. And he points to sort of three ways this can be very, very helpful. The first is it’s good when there’s an uncertain path to a vision of the future. That’s his phrase, uncertain path to a vision. You bring capabilities together. You catalyze a group of partners. You unleash the learning of this group together. And because the whole group learns faster, they are therefore better at innovating against that uncertain path. He focuses a lot on the idea that when you work this way, you learn tremendously fast, and that lets you innovate faster. He says this is also beneficial when you need more capabilities than exist in one company, or if you’re trying to build a complicated solution. And I think Didi is an example of that and what these automakers are doing. There’s no way these current automakers, Ford, GM, Toyota, whatever, they simply don’t have the capabilities to do software and autonomous vehicles and ride sharing. They have to reach outside of their industry to pull those capabilities together. Last one, he also says this is a particularly good approach when you’re facing disruption. You don’t know what’s going to happen. You have to change quickly, highly adaptable, rapid learning, that sort of thing. So those are his three. And this is much more complicated than the platform business models I’ve been talking about. This is much more than a marketplace. It’s not the sort of simple, standardized, and therefore scalable interactions like hailing a car or a taxi. This is multilateral. engagement, interactions, collaborations between lots of parties where the goal is to sort of unleash their creativity to have a lot of joint learning, a lot of innovation, a lot of adaptation, but it’s much more complicated than just simple buy and sell transactions. So he says this is about innovation, learning, and adaptation. He calls it strategy without planning, which I thought was a Bring everyone together, a lot of collaboration, and we’re going to start to learn and innovate and adapt without a plan. Now, the trade-off, he says, is this is all very, very inefficient. There’s a reason why traditional companies built these very highly efficient supply chains, because you saved money. You had a very focused approach, the pipeline. And you could even argue that a lot of marketplaces and, you know, platform business models are also highly efficient. But we don’t have this in an ecosystem approach. Those models are good when you have a stable plan, a stable business. But if you’re just sort of amorphous and adapting, okay, you’re no longer efficient. You’re adaptive, but you’re not efficient. And last point on this, ecosystems can actually have some fairly powerful competitive advantages. So if you can do this approach, if you can catalyze an ecosystem and build one of these things, the first benefit is you get network effects. You know, big surprise. The more people that join the ecosystem, the more companies that join, the smarter we all get, the better we are at innovating, the whole thing becomes better. An ecosystem with six partners is probably better. more valuable than one with two. It also tends to collapse the market or the industry to one or two players. Now if you’re a small company and you’re seeing two major ecosystems like Alibaba and Tencent, okay you’re probably going to join one of these. It’s very unlikely you’re going to create a third ecosystem. So it does sort of collapse the market, network effects, that sort of thing. because it’s no longer just the scale of one company. I have a factory that’s three times bigger than you. I have the scale of the entire ecosystem that I can lever against a smaller player. So you’re looking at the scale of the sales of the entire ecosystem, the volume moving through it. Obviously, that’s going to be a lot bigger. And finally, you can have a rate of learning. advantage, obviously. I’ve listed this in the past as one of the competitive advantages and also as one of the dimensions of the Smile Marathon. But you can get to a point where you’re learning so much faster than your competitors that it really is a competitive advantage. So we’ve got at least three network effects, economies of scale, rate of learning that come from this. And that is more or less his argument. I mean, he writes a lot more about this. But the sort of what is the advantage you can have as an ecosystem? What’s your? edge. He lists five things. You can leverage network economies, you can focus your company on what it’s really good at, you can harness the power of partners in areas they excel at, you can learn and innovate faster, and you can become more agile. And that’s it. I mean, that’s a brief summary. I’m going to talk more about this. Peter, if you’re listening, sorry about that. I know that’s a very short, very brief and not awesome summary of your… You’re a very well-done book. I’m going to talk about this more in the next podcast. We’re going to build on this. But I want to kind of tee up those ideas. When you think ecosystem, think of collaboration, either a business model based on collaboration or an entire industry based on collaboration. And within that, it can be about innovation. It can be about learning. It can be about facing disruption. It can be about offering a solution that and customized than any single firm could ever do. There’s a lot of reasons to think that this type of approach is gonna become more and more common. And that is it for today. I’m pretty wiped out. I’ve got a couple more days here in Phuket then I’ll head back to Bangkok. It’s really been fantastic down here. It’s, you know, obviously Phuket has been really hit, you know, incredibly hard by the whole COVID situation. This is a tourism island. And there’s no tourists coming in. There’s folks from Thailand, there’s folks like me that are local, but the international airports are still closed down. So on the western side of the island, everything is just shut down. The hotels are shut down, the restaurants are shut down, the Starbucks are shut down, the 7-Elevens are shut down. There’s a couple here and there that they’ve kept open, but it’s really shocking to see. On the flip side. It really is nice to see some of Thailand’s most famous places without the hordes of tourists that are usually on them. It’s really quiet. It’s pretty. You can walk the beach and there are not just sort of tons of people. So there is a nice aspect to it. Maybe this was what Thailand was like 30 years ago before it became sort of, you know, such a massive tourist destination. But obviously it’s really hard on everyone who works here. So I’ve been hunting around the island looking at things and it was really great until I was walking down the sidewalk last night and I almost stepped on a fairly large snake and it was not one of the harmless ones. I don’t think it was a cobra but it was a good meter to a meter and a half three inches, two inches in diameter and it was just coming out of the sewer going across the sidewalk up into the Yeah, that made my just sort of casually strolling around, looking up at the scenery a little less casual. I’m looking down at the ground a lot more than I was yesterday. But it’s pretty spectacular here overall. Anyways, that’s it. I hope this is helpful. Any feedback you have on sort of the uber graphic, the summary graphic of the content would be really helpful. I want to try and make that as sort of simple and understandable as possible. So the feedback is a huge help. But otherwise, thank you so much for listening. And I hope you have a great week, and I will talk to you next week.