I was in Kenya recently and got a chance to play with Jumia and Jumia Food, the big ecommerce apps in most of the big African countries. Especially Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Egypt, Ghana and Egypt. And Jumia’s annual report is pretty interesting reading.

In terms of strategy, Jumia has pretty standard marketplace platforms for products (Jumia) and food delivery services (Jumia Food). Plus, it has been building Jumia Pay, which could become a reasonable payment platform. These three platforms are still in the earlier stages and are pretty basic in functionality.

However…

Jumia does provide fantastic details about how ecommerce is different in early stage and lesser developed economies. With China, Japan, South Korea, and the West, we get a clear picture for what ecommerce looks like and how it evolves in developed economies. But in Southeast Asia and Latin America we get a mixed and muddy picture. Parts are developed. Parts are developing. Parts are declining. I found Jumia gave me a better checklist for understanding what to look for in places like Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Overall, the risk section of Jumia’s 10k is really worth reading. And I took away 5 lessons on the risks and economics of ecommerce in early-stage and underdeveloped economies.

But first a few points on Jumia.

Marketplace Platforms Are About Ecommerce Development, Not Demographics

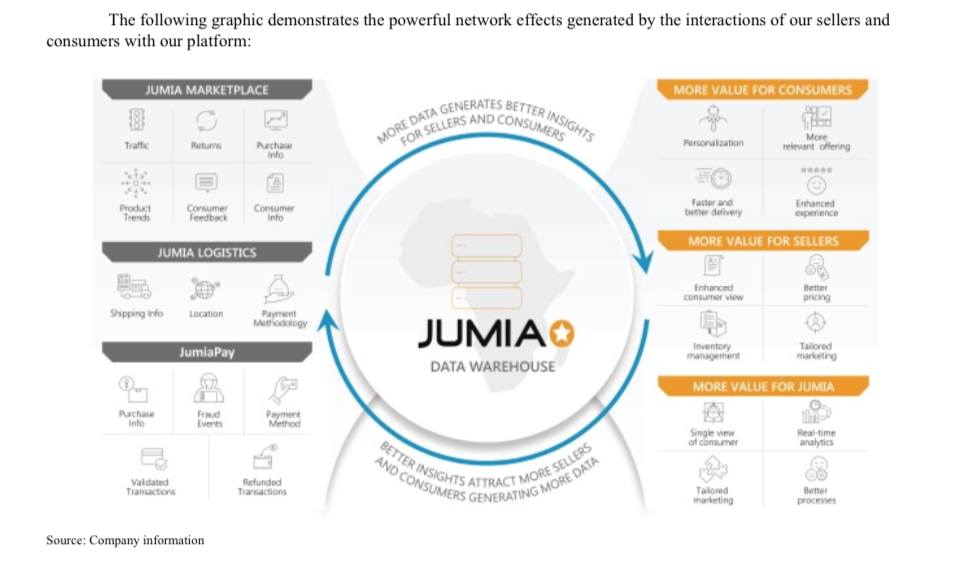

Here is the standard platform graphic from Jumia’s annual report.

It points to a marketplace, logistics and payment. And how these creates a virtuous cycle (i.e., a network effect). Basically, ignore this. Jumia is two marketplace platforms and maybe a payment platform. With network effects that are mostly happening at the national and regional level.

The company was founded in 2012 in Nigeria and really expanded rapidly geographically. It had a proven business model and a compelling story about the size and growth of Africa’s consumer markets. Think pictures like this (which is Johannesburg).

Fast forward to 2022 and Jumia only has +8M annual active consumers. That low compared to the 1.4B people in Africa. And any time a company gives you annual, and not monthly or daily numbers, it’s a red flag.

So, what is happening? Basically, the Africa story and above picture does not match the reality. This is what most Africa really looks like (which is Uganda).

I once asked President Michael Jensen how Alibaba choose which international markets to expand into. And he said (paraphrasing), it was not about demographics (big versus small populations). It was about the stage and rate of development of ecommerce in the country. That means digital infrastructure (connectivity, data plans, etc.), physical infrastructure (warehouses, retail, roads) and government (payment systems, regulations). Ecommerce is about digitizing and entire ecosystem. That, not big versus small populations, determined the trajectory.

That’s what I think about with Jumia. With that, here are my 5 lessons from Jumia.

Lesson 1: Underdeveloped physical infrastructure makes ecommerce operations more complex and expensive. Delivery, in particular, can be very difficult.

Take a look at how Jumia describes its infrastructure risks (from 10k).

A lot of Africa doesn’t have addresses. People use cash. Traffic is bad. Distribution and logistics are highly fragmented and inefficient. Moving physical things around many of these countries is just difficult, slow, and expensive. And there is no easy solution to these problem. It just makes ecommerce more expensive and difficult.

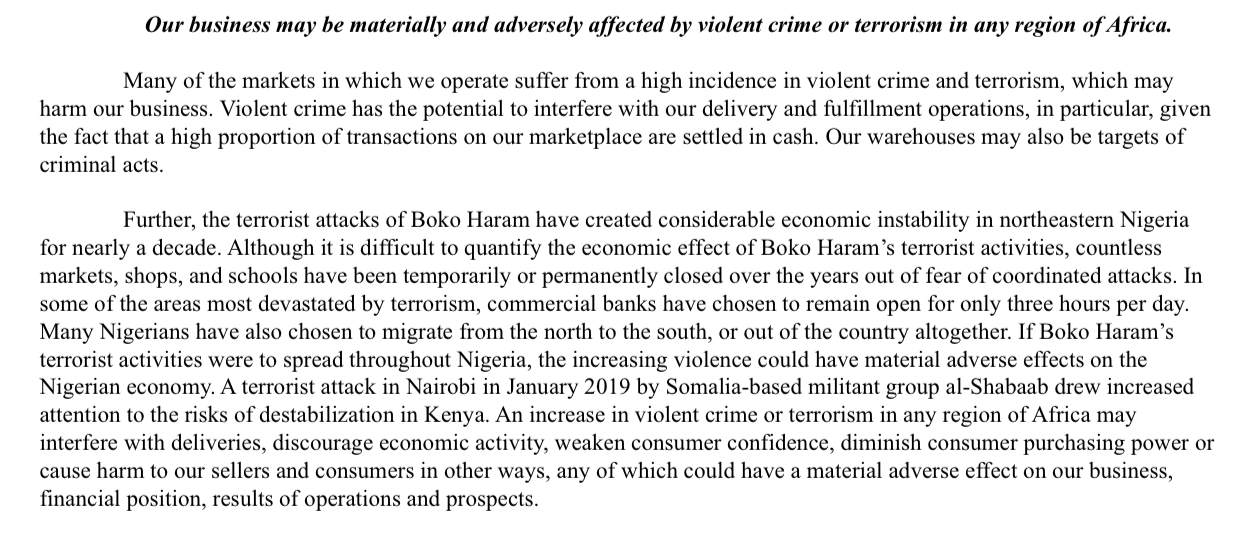

Lesson 2: Decentralized operations are more difficult with corruption, crime, and limited rule of law.

Platform business models are about coordinating the activity of various users. Decentralization, by definition, means giving up direct control and acting more like a government that sets rules and incentives. And does some enforcement. This type of business model becomes much more difficult in economies with corruption, crime and limited rule of law. These are not environments where you want to give up direct control.

As mentioned, delivery is a particularly problematic part of ecommerce in Africa. From the 10k:

It gets worse.

And…

This type of environment makes a business model with decentralization and asset-lite logistics much more difficult. And all this impacts the unit economics.

Lesson 3: Underdeveloped digital infrastructure limits the market and growth.

Underdeveloped physical infrastructure can create operational problems and costs. But it is the digital infrastructure that determines market size, growth, and revenue. And this is problematic. Here are the financials for Jumia.

The gross profit is still only $110M (and +8M annual activity users). It could certainly grow and Africa’s 1.4B people offers this possibility. The company is targeting a very large market. But the rate of growth is determined by the digital infrastructure, which is still quite limited.

Lesson 4: Merchants, brands, and the supply side just have lots of problems.

For me, the merchant side is the biggest question. Consumers are getting on board. Everyone in Kenya is on MPesa. But how fast will the merchants digitize their operations and move online? How sophisticated are they? How well managed are they? How financially stable are they? How much education do they need?

Marketplaces are requires lots of consumers and lots of merchants. And many of Africa’s merchants are just not that advanced. Look again at the picture above the roadside stalls. Going online is a long-ways away for many of them. Management and finances are also a problem. How fast sellers are moving online would be my first question to Jumia management.

Lesson 5: Digital talent is more challenging in less developed countries.

Virtually every company I talk with mentions digital talent as their bottleneck. It is hard to get software people anywhere. And it is hard to train existing management in digital tools and operations. This problem is bigger in Africa.

Jumia actually has an interesting organizational structure. It is a German company and its research and technical staff appear to be in Porto, Portugal. In Africa, it appears to be mostly local management and operational staff.

***

Overall, I found the risk section of the Jumia 10K to be very helpful in crystallizing my thinking for developing economies. It laid out the risks much more clearly.

This all comes back the three factors that create economic value:

- Market size and growth

- Competitive advantage

- Unit economics

I’ve talked about this in my Moats and Marathons books. And I’ve argued that only #2 is really under your control. Jumia has this for sure. But #1 is still small and growing slowly. However, there is obviously long term potential.

For Jumia, #3 is really the problem. Most of the mentioned issues impact the unit economics of the business, regardless of Jumia’s competitive strengths. Jumia is struggling with difficult unit economics. How they eventually play out in most of Africa is not clear to me.

And this is my big take-away. Ultimately, platforms are “ecosystem orchestrators”. They reach out and interact with a greater ecosystem. The state of that ecosystem ultimately determines the problems they must solve to function. And this is what determines the ultimately cost structure and economics.

This is something to think about when companies like Mercado Libre talk about expanding into Northeastern Brazil. Or when Shopee expands into Southern Philippines.

That’s it for today. Cheers from Sao Paulo, jeff

———

Related articles:

- Why I Really Like Amazon’s Strategy, Despite the Crap Consumer Experience (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Big Questions for GoTo (Gojek + Tokopedia) Going Forward (2 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- Why Netflix and Amazon Prime Don’t Have Long-Term Power. (2 of 2) (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- n/a

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Jumia / Jumia Food

Photo by Clodagh Da Paixao on Unsplash

Photo by Photos By Beks on Unsplash

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.