Years ago, I started mapping out the evolution of Alibaba with pictures. I was having a hard time keeping all the moving parts in mind. And I was becoming more and more convinced that digital company development is path dependent. What comes next depends on what just happened. Microsoft is only capable of its current moves in cloud and ChatGPT because of its previous development work in Windows, Office and Teams.

So I started making my diamond diagrams, which people either love (or at least like) or hate. My co-author Jonathan really dislikes them and keeps deleting them from our latest book.

For Alibaba, I mapped out their business in 7 slides over time. And I think this made it really clear what they were doing in new retail. I will give my explanation of new retail in Part 2. But first, I thought I would lay out Alibaba in 7 slides.

First, It Helps to Separate Hyperscalers from Digital Natives

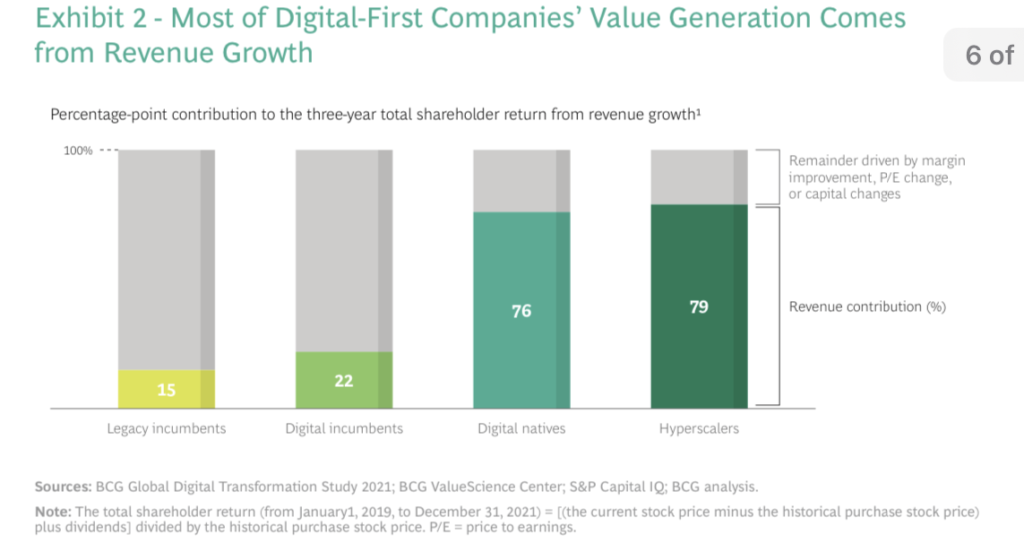

Last year, BCG wrote a nice article titled Rise of the Digital Incumbents. It put companies into four buckets:

- Digital natives, which are born as digital creatures. Think Zoom, Roku, Pinterest and Atlassian.

- Hyperscalers, which are a sub-category that are uniquely large and fast growers. Think Google, Facebook and Microsoft.

- Digital incumbents, which are established companies that have mostly made the difficult transition to digital operations. Think GE and Haier.

- Legacy incumbents, which aren’t really digital yet.

This is a pretty helpful categorization. BCG broke out hyperscalers as a small subset of digital natives. These are the digital creatures that have economics and structures that let them grow much bigger and faster than others. Think Google, YouTube and Facebook. Basically, the digital giants I often talk about. They call them hyperscalers. Their growth has a lot to do with their platform business models.

The key point BCG makes is that most of the value created by hyperscalers is from their revenue growth. The demand side is the big lever that really creates value. When you look at digital incumbents, like supermarkets going digital, you’re going to many areas of value creation (such as increased productivity and process automation). But for hyperscalers, you really want to look at growth. Both in core businesses and in ancillary opportunities.

Which is exactly what Alibaba has been doing for +20 years.

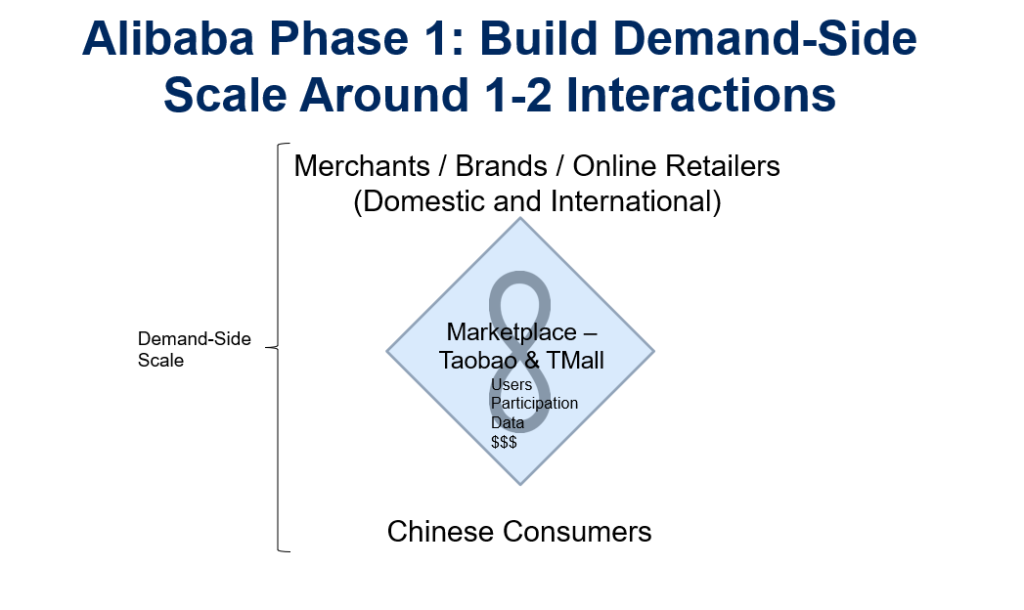

Phase 1: Build Basic Demand-Side Scale Around 1-2 Core Interactions.

Alibaba started as a simple B2B platform. And then Taobao, launched in 2003, connected consumers with small merchants and entrepreneurs. It was closer to C2C than B2C, a sort of virtual bazaar or village marketplace. And it was a response to eBay entering China. They thought eBay doing B2C would eventually lead to eBay doing B2B. So they moved into B2C as a defensive move. After Taobao came Tmall (originally Taobao Mall), launched in 2008, as a more controlled site. It had established brands / merchants and licensed distributors, making it more like a shopping mall than a bazaar.

You create a platform (digital better than physical) that enables two different users groups (in this case consumers and merchants) to connect and do transactions. The purpose of the platform is to drop the transaction costs (search, coordination, negotiation, information asymmetry) such that these groups can do transactions. People can find products to buy, people to date, information they want, and so on.

This model has the potential to grow dramatically. But in the early stage, you need to get a critical mass of users on both sides of the platform. And get as much activity as possible by users. And ideally, you start to build network effects (also called demand economies of scale) such that your service improves with use. Network effects can really add tremendous value in these early stages.

But the goal of stage 1 is to get the platform functioning around 1-2 core interactions. This is actually pretty hard and most fail. Being early to the market (which Alibaba was) helps a lot.

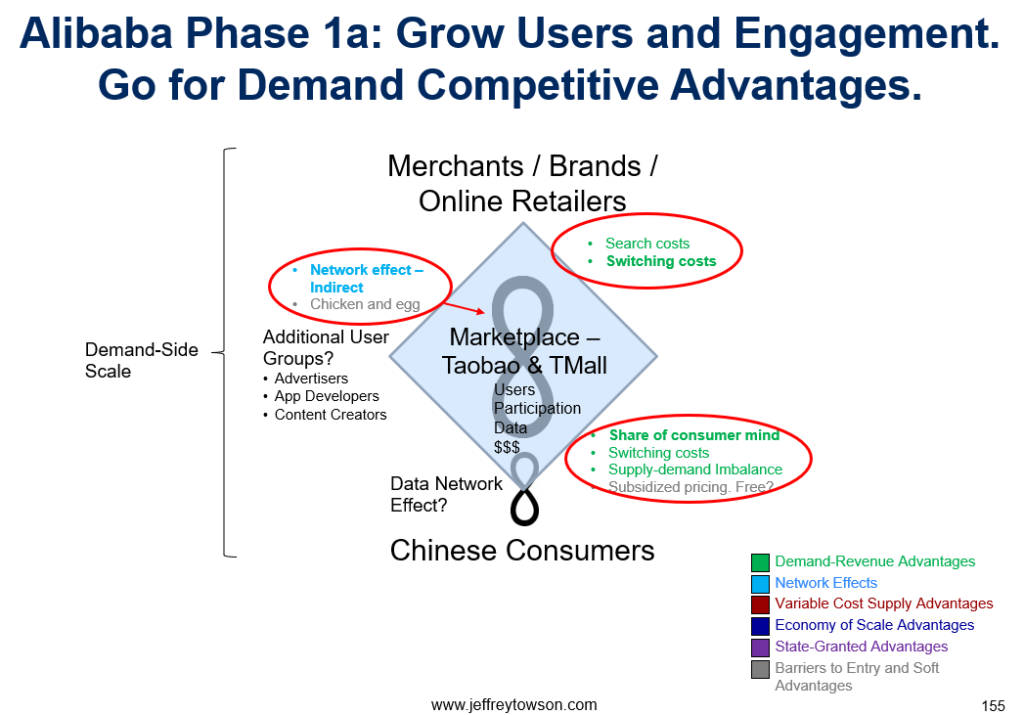

Phase 1a: Increase Demand-Side Scale. And Start Adding Other Advantages.

Once you’ve got a basic platform running, you want to start creating additional demand-side scale. That means growing users, participation and data (the core intangible assets that create the digital platform). And, if its e-commerce, you start personalizing on the consumer side. This improves the consumer experience at the individual and the aggregate level.

Alibaba has been doing this for a long-time. It’s why you always hear the management talking about personalization and curation. The site has been optimizing itself overall and to each individual consumer forever. Improving the user experience is key for increasing engagement and demand-side scale.

The site can also start trying to build other competitive advantages. I’ve put these in the graphic below. For those that have read my Moats and Marathons books, these should be familiar.

For consumers, that usually means creating habits. Getting people used to buying on impulse (‘one-click buying’). You make it fun. And shopping becomes about purchasing and entertainment. You speak to needs and aspirations. It’s not just about finding a product you want and then buying.

For merchants, the site can start building in switching costs. Merchants build up customer bases on the site. They build up revenue coming from the site. They start getting the data. They start developing new products based on the data. That’s all great for them, especially small merchants. But it also makes it harder to switch back and forth to other e-commerce sites quickly. They become invested in the success of the platform.

***

The above two stages are pretty standard in e-commerce. Not much new there in terms of China. Just bigger numbers. But Phase 2 is where China starts to diverge.

Platforms tend to beat product companies (also called pipelines and vertically-integrated companies). They can subsidize pricing between users groups (it’s why Google, Facebook and WeChat are free to consumers). Similarly, three-sided platforms tend to beat two-sided platforms (more ability to subsidize prices and do creative stuff that your competitors can’t). And so on. Having more sides to a platform is usually an advantage.

So these platforms start adding new user groups. They can add advertisers (usually advertising agencies are platforms themselves that connect ad supply and demand). They can add content creators (in this case Youku-Tudou). And they can start to add application developers (really important). These are the companies that build new software that runs on top of the platform (think of all the apps that run on Google Maps and Earth. Just count the number of APIs available).

And this is when things get really cool. Because with multiple users groups and lots of data, you can start to go identify and exploit new use cases. You can start to offer entirely new services. And this is also where digital China really gets pretty crazy. China’s platforms jump into everything: payments, credit, money market funds, bicycles, on-demand delivery, local food services, healthcare, etc. They just keep adding user groups and taking on new use cases. It’s crazy how fast they move.

In China, the net result of Phase 1 is tremendous scale on the demand-side. Hundreds of millions of users doing all sorts of services. That is where the power is in the consumer-facing markets of digital China.

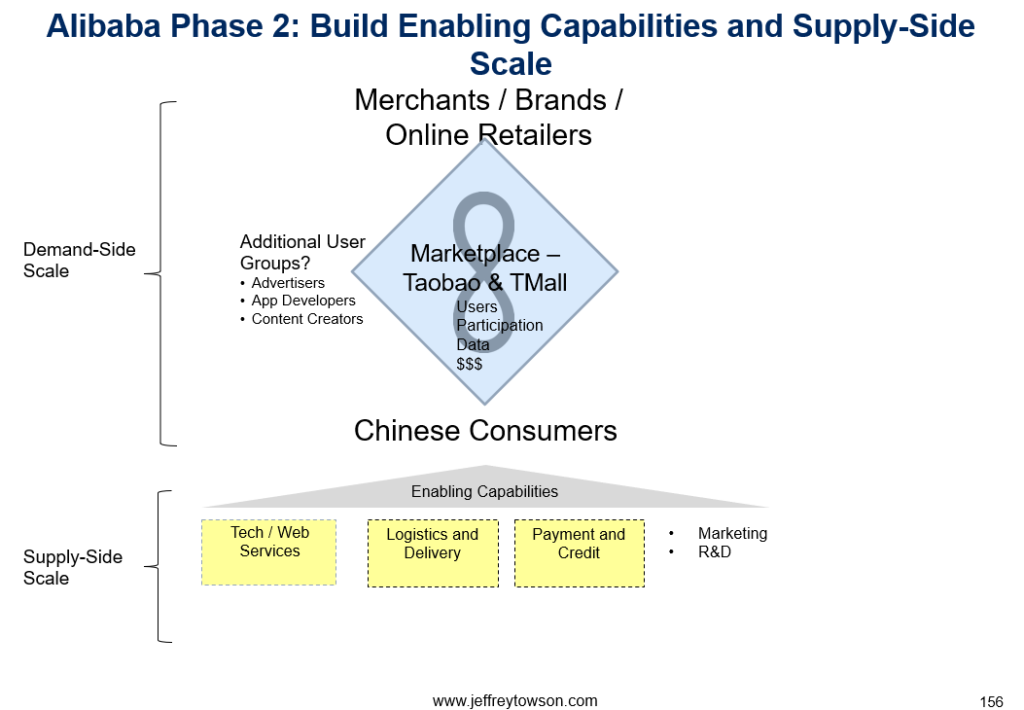

Phase 2: Build Supply-Side Scale

Along the way, these platforms have been increasing their spending on enabling capabilities and some fixed costs, such as IT / web services. Probably logistics. And likely R&D. And as they get larger than rivals, they can start to get scale effects on the supply-side. If you are spending 20% of revenue on IT services and you are 3x larger than a rival, then you are outspending them on this.

These supply-side economies of scale are common in software companies in both China and the rest of the world, especially in IT/Web services.

What is different in China is that internet companies are not afraid to get their hands dirty – and go into managing physical assets and activities on the supply-side. They hire tens of thousands of delivery riders. They built huge numbers of warehouses. They build and buy supermarkets. They build their own delivery drones and autonomous vehicles. They open physical banks. They are currently building clinics.

Western digital giants tend to stay purely digital creatures, doing software in nice business parks. But Chinese companies are comfortable doing hardware and manufacturing (it’s all done in China anyways). And they will go into services, customer service and other labor-intensive activities (which are cheaper in China as well).

And while this is operationally complicated – and decreases the attractiveness of their economics – it also gets them a degree of competitive protection from China’s ferociously competitive online world (yes, much more than in the West). When Chinese digital companies get market leadership, they will often diversify into more services (Stage 3) and go for supply-side scale, including with physical assets and activities. This gets them some degree of competitive protection. You can really see this in companies like Meituan and JD.

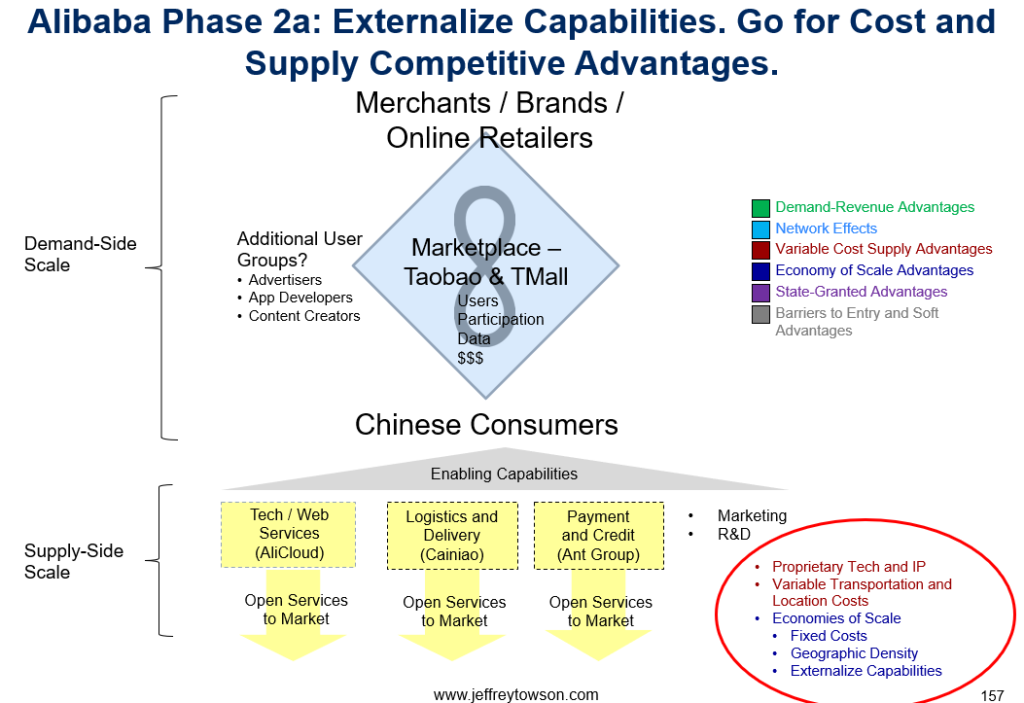

Phase 2a: Add Supply-Side Scale. Externalize Capabilities Where Possible.

This process continues on the supply-side. And there are additional advantages you can build like government advantages (yes, it’s important). You can also get cost advantages through purchasing costs, location / transportation cost advantages and other.

However, the most interesting move is when companies externalize their core capabilities.

- Amazon was an early pioneer in this, turning its IT/web services capabilities into Amazon Web Services.

- Alibaba did the same with Alicloud.

- Alibaba and JD both did the same in payments by creating Alipay / Ant Financial and JD Finance.

- JD did this with JD Logistics.

By turning an internal capability into a market-facing business, the company gets even greater scale on the supply-side. It sometimes can also get you a second business (note: AWS throws off tons of operating cash flow per year, which subsidizes delivery). And sometimes it even gets you another platform business (Ant Financial, AWS).

***

That’s it for today. In part 2, I’ll go through the rest of the ten slides.

Cheers, jeff

———

Related articles:

- How Alibaba Freshippo and Dingdong Got to Profitability in Ecommerce Groceries (1 of 2) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- Dingdong vs. Oriental Trading: How to Spot the Specialty Ecommerce Winners (1 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Can Dingdong Win in Groceries and Specialty Ecommerce? (Asia Tech Strategy – Podcast 90)

- How AB InBev and Zé Delivery Are Changing Ecommerce in Beverages (Tech Strategy – Podcast 139)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Ecommerce

- Marketplace Platform

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Alibaba

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.