This week’s podcast is about rate of learning as a concept. That is the digital version of what was originally called the learning curve and the experience effect. Rate of learning has gone from an important idea in production-intensive products to a digital requirement. But the key question is when does rate of learning become a competitive advantage? This podcast is my answer.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

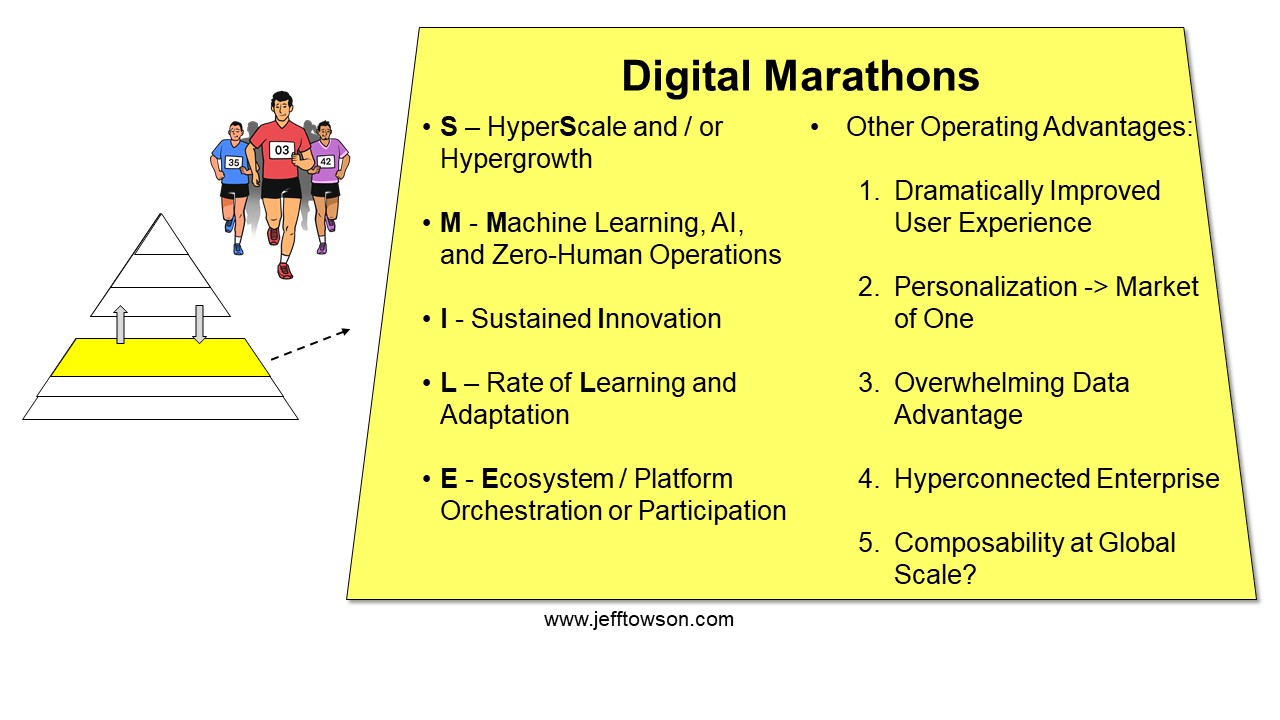

Here are my Digital Marathons list. Note the L.

Here are the competitive advantages. Note CA7.

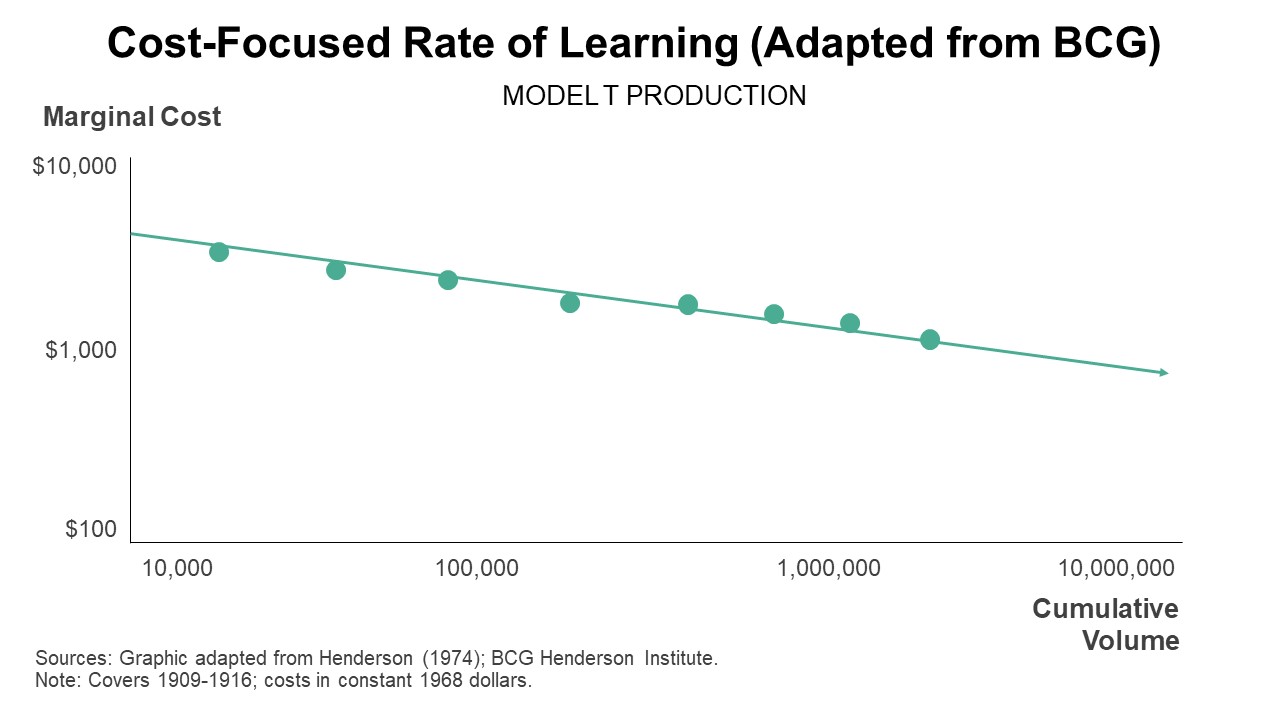

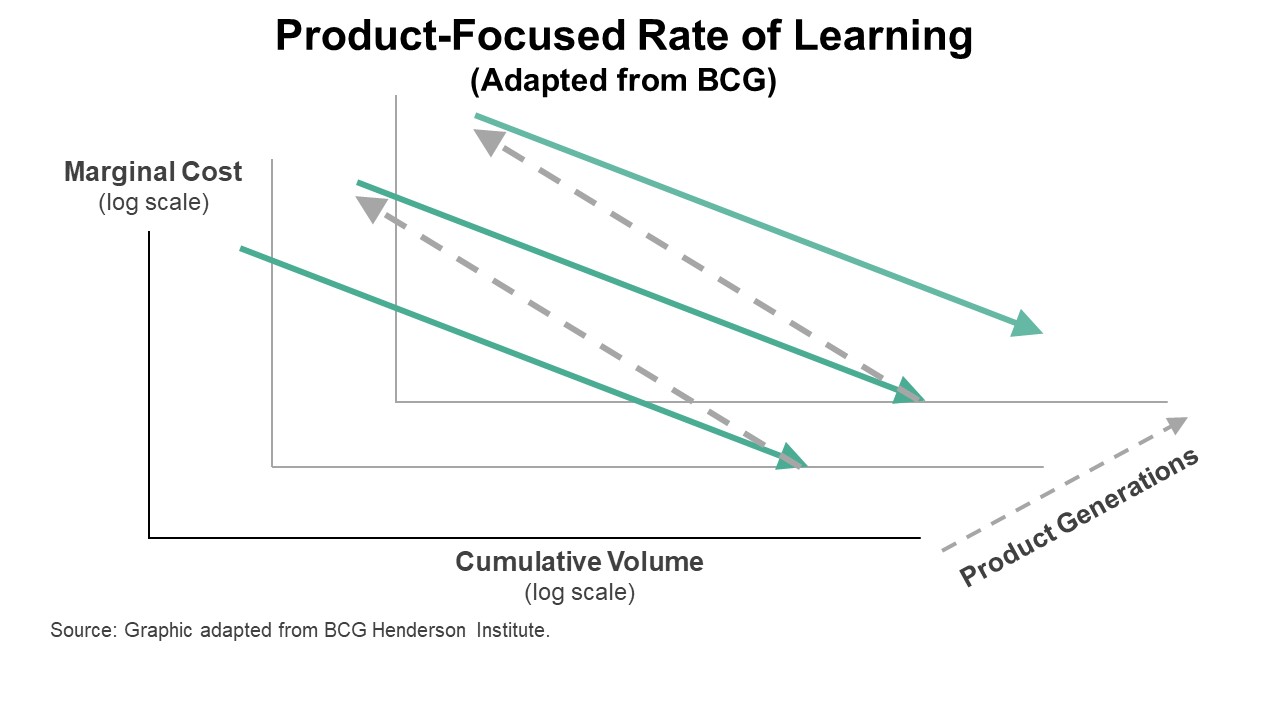

Here is cost-focused rate of learning, product-focused rate of learning and algorithmic learning.

—––

Related articles:

- Why I Really Like Amazon’s Strategy, Despite the Crap Consumer Experience (US-Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Big Questions for GoTo (Gojek + Tokopedia) Going Forward (2 of 2)(Winning Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Learning Curve and Experience Effect

- SMILE Marathon: Rate of Learning and Adaptation

- CA7: Rate of Learning and Process Cost Advantages

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Amazon

- Tencent

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash

——-transcription Below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Tausen and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast where we dissect the strategies of the best digital companies of the US, China and Asia. And the topic for today, Amazon Tencent and when rate of learning becomes a competitive advantage. Now this one is actually, I don’t know, I’ve been working on this maybe let’s say two years. The idea of… rate of learning, which is a huge idea. It’s very, very important. It kind of comes out of what’s often called the experience effect or the learning curve. I mean, people, especially business people, have been writing about this since 1930, 1939, about that time. And it was a huge part of strategy for a long time. And then it kind of fell away for a while. And then it came back because digital and data is changing how companies learn. And it really plays out at quite a lot of levels of a company, the operating levels as well as sometimes the competitive advantage level. And I’m gonna kinda give you my take on how to think about all this and then when it actually becomes a competitive advantage. So hopefully this will be useful. It’s gonna be some history, some theory, and then a couple companies, and that’ll be the topic for today. And let’s see, other stuff. Companies coming up for subscribers. I don’t really have, I’m sort of short on the list now. I’ve been sort of burned through the companies that were on my to-do list. If you have any that you think would be worth talking about, please send them my way. China, Asia, or the US would be great. I’ve gone a little bit into Brazil and some other places, but I’m trying to sort of stay focused on those three markets. But yeah, anything where you think a company’s really moving and there’s a lot to learn, please send it my way. For those of you who aren’t subscribers, feel free to go over to jefftausen.com. You can sign up there. Free 30-day trial. Standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing or website is investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Now, I have three concepts for you today. which will be in obviously the concept library on the webpage. Number one I’ve talked about before, which is the smile marathon, which is, for those of you who aren’t familiar, this is the idea that certain operating activities can start to become an advantage if you stay at them long enough and are focused long enough, which is why I call them marathons. You can sort of slowly pull ahead and if it’s in the right activity, it can effectively become an advantage, which is I call them marathons. And the books I’ve been writing are called motes and marathons because that’s, I think, where you can really build an advantage. And the acronym I’ve used is SMILE, S-M-I-L-E, five different types of digital marathons you can run. And the L in that, which is the point for this, is rate of learning and adaptation. And it really follows out, falls out. of what I’m going to talk about, this idea of learning as an advantage where you can pull ahead of your competitors over time. And it’s really been broadened not just to learning. When learning was first sort of described as a concept for management, it was a lot about having a stable market like automobiles. and you are making a product for that market and you do it over and over and over and you get better at it. So it kind of implied learning was about becoming more efficient and productive against a relatively stable demand, i.e. people buying cars. That has somewhat changed with this idea of now people are thinking about maybe learning is not just about being more efficient and effective and productive against stable demand, which would be rate of learning. maybe it’s also about adaptation. That what we’re really good at doing as a company is learning and adapting to changing market conditions. So that’s why in sort of digital marathons I’ve listed it as rate of learning and adaptation. So that’s concept for number one. I’ll go through that more as we get to it. Number two is the experience effect, which is sort of an old business term from BCG. Back in the 1960s, 1970s was a big strategy topic. Bruce Henderson, the founder of BCG, who the Henderson Institute is now named after. I think he’s the one who came up with that idea, that term, the experience effect. It’s also called the learning curve, but usually for business people call it the experience effect. We’ll talk about that one quite a bit. And then third one is a competitive advantage, which is on my competitive advantages list. which is rate of learning and process cost advantages. And I will go into that in detail too. So there’s sort of three fairly big ideas and I’ve talked about one of them before, the other two I really haven’t. So hopefully this will be helpful, but yeah, it’s gonna be a bit of theory today. Now I guess we, well let me put a little precursor before I go back sort of into the history of this, that when you start talking about rate of learning, I’ve been talking about this like, if you go through my six levels of competition, it’s been playing out at every level. It’s pretty much been part of every bit of this, just sort of a little bit below the surface. So rate of learning would be how fast can a company, learn about an environment, market changes, tactics, whatever. How much could a team within a company learn? How fast? How much would individuals learn? So it can play out sort of at multiple levels. But when you talk about rate of learning, you know, I mentioned this in tactics quite a bit, level one on my six levels, you know, the constant back and forth between companies, the endless sort of marketing initiatives and counter moves. growth tactics, how to break into a new market. All of this is a lot about how quick can your company learn about what’s happening with the market, what’s happening with competitor moves. This used to play out for businesses 50 years ago. This would play out over a month. Then it’s kinda gotten faster, then it was weeks. And now with digital stuff, we see sort of learning moves and counter moves, which would be under tactics. I mean, they can play out in seconds. So the time scale has been changing, which is interesting, but digital operating basics, which I’ve talked about a lot, you know, that’s about building digital core of operations. And the way I’ve described this, if you look at these charts, I always say it’s about, you know, getting faster, smarter and better. That’s what it means to have your operating activities digitized, digital operating basics, faster, smarter, better, you know, growth, fast, speed. excellence, that’s all about just being better. Well, that has a lot to do with learning. It has a lot to do with being very data driven in management and operations, which in practice means a lot of data analytics, a lot of sort of key, learning about key operating activities, all of that. Then we can go up to level three, which would be digital marathons. Okay, that gets you to rate of learning and adaptation, which I just mentioned, but then we can also go up to a competitive advantage and think about it there. And what happens when you start breaking it down this way, especially when you start talking about operating activities, not modes, this idea of learning becomes broader. It goes from, hey, we’re learning, to, hey, we’re adapting. We’re not just sort of meeting stable demand and getting more efficient because we’re learning how to do it better, but we’re also adapting to changing markets faster than we used to. So learning kind of tees up this idea of adaptation, which is something BCG talks a lot about now. They’ve got books written about the adaptation advantage, but it also kind of leads right into this idea of experimentation. Well, how do you learn? I mean, you can look at your numbers and it’s a lot of data analytics, that’s how you can learn. But it’s also about running experiments where you might change aspects of a mobile app or a website or change your inventory or change something and then look for the results in the data and that’s experimenting. And companies that are good, especially digital ones, they are running experiments all the time, tens of thousands of them every year. Well, that’s a part of learning too. So it’s kind of like, And then maybe the last bit would be innovation. We’re trying new things based on what we’ve learned and that’s how we adapt. So these all kind of blur together at a certain point, learning, adaptation, experimentation, innovation, all of that kind of rolls together into operating activities. The tactics, the digital operating basics, that all kind of just sort of melds together at a certain point. And consulting firms do kind of a lot of business about how to become more agile, how to become more data-driven, how to become more experimental, how to be innovative as a company. It’s all kind of that same thing, but that’s the language I use. So with that, let me sort of jump back in time and go through really some really big business ideas that have been around forever. The first one is learning curves. Although this wasn’t really a business term, this was a psychologist. who came up with this. You know, you’re talking back in 1885, a German psychologist named, I don’t know how to say his name, Hermann Ebbinghaus. He’s the one who first sort of came up with this term learning curve. And it’s a pretty simple idea, which is the idea is if a human being does something over and over, they get better at it. If you repeat a task, you become more proficient at that task. Now he was testing things like how many words could you remember? And you know, you give people words, terms, and then have them try and remember. And it turns out as they, you know, you could test them and quiz them and all that. And as you did that, people got better, which is, you know, obvious. We, you know, we’re human beings. We get better when we practice things. So. He basically plotted that out on a graph. On the Y axis you put proficiency, which is obviously how good you are at that activity. And that could be measured many ways, speed, how fast you are, how many words do you remember, how good are you at it, proficiency. And then on the X axis you put experience. How many times have you tried this test? How long have you been studying it? And if you plot those out, the y-axis and the x-axis, you get a curve. And he called that hence the learning curve. I mean, it’s literally a curve on a graph. And those can look certain ways. They could be sort of an S-curve where it goes up, it goes sort of flat for a while, then accelerates upward, and then it flat lines out again, which would mean like, as you get experience, you learn slowly at the beginning, but then you accelerate and learn faster. And then at a certain point, you don’t really learn anymore, you flatline. It could be a linear curve, or just sort of a line up to the right. So, you know, the more experience you have, the better you get, and it just keeps going up. What people tend to talk a lot about is what they call a power law, which is basically it’s an exponential curve, but instead of going up to the right, it goes down to the right. So basically, when you get a little bit of experience, you learn very, very quickly. And then as you get more experience, your rate of learning falls, or your proficiency, but it basically curves down to the right. And that turns out to be a big deal because when you start looking at things like how much does it cost to do something, as you get more experience, basically the cost falls often like a power law. And that’s kind of what we’ll talk about a bit because it turns out if it’s a power law, which is an exponential and you put it on a log curve, then it looks like a straight line. And I’ll put an example of that in the show notes, which is basically, let’s say the famous example everyone always uses is Model T. Ford’s. Henry Ford, he used to talk about this phenomenon and basically said, look, when we make the Model T. Ford, every time we double the cumulative production, which means all the cars we’ve ever produced, that’s the x-axis. So as we move to the right on the x-axis, every time we double the total cumulative production, our cost to create a car drops by about 20%. So that would be the proficiency, the y-axis, in this case, the cost per car. Now, that’s pretty much what they talked about. You could call that a learning curve. Sounds pretty easy. The simplest version of the learning curve is practice makes perfect, which everybody kind of knows. Okay, but that was psychology that was looking at people. When you start to look at businesses with this idea, well, it becomes a lot more complicated very, very quickly. The first thing you jump out is, wait, are we talking about individuals get better or are we talking about teams of people get better? like a team on an assembly line, would they get better or does it happen at the team level or just at the individual level? And then you could go further, well, what about at a larger organizational level, can the entire company get smarter and more proficient? Do we have learning curves for an entire industry? Maybe not just the companies, but everybody in this industry? So that’s kind of an interesting question. And then you get to, well, what about proficiency, like the Y axis? What does that mean? Is it the cost of doing a certain task? It is the cost of creating a product like a car? Or maybe it’s just the time to do it that you get faster. But if it’s a labor intensive thing, if you get faster, you also get cheaper because of the labor costs. So is it productivity? Or maybe it’s not about cost or time, maybe. the proficiency metric we’re looking for is performance. We want fewer errors in the cars. We want higher test scores. Maybe proficiency is about making the products better. So you start to dig into these things and you’re like, okay, I’m not totally sure what’s on the Y axis. And you can do the same thing on the X axis. What do you mean by experience? Is that the number of times we’ve built this car overall? Or is it the number of times built by this specific team of 10 people? Or maybe it’s the amount of cars built just in the last week. Maybe it’s not over years, maybe it’s just over this month. Or maybe it’s by all the companies and not just one company. Or maybe it’s all the companies in an industry. So experience is a bit of a fuzzy term, depending how you do it. And then you really get to the big, big question. How does this happen? Because if you’re gonna count on this as a strategy or a competitive integer or anything, you kinda gotta know how, like what is the mechanism? Is it just happen on its own? And that turns out not to be true. You actually, to achieve a learning curve in a company or a team, you actually have to have a system. It doesn’t happen on its own. So what are the mechanisms by which this happens? And I’ll give you some examples on this, but one of the things that jumps out immediately on that should be, okay, wait, you just said this is about learning curves. Learning curves are about people, human learning curves. So if I have a business, let’s say assembling cars, which is 90% about labor and only 10% about equipment, machines. is there a bigger learning curve in that business that can be taken advantage of than let’s say manufacturing the parts, which is gonna be a lot more about the equipment and a lot less about the human beings. Do learning curves as an idea, as an advantage, do they depend on how much human labor is deployed in an activity? Because if it’s all just machines, nothing is learning. Well, not in the old days. If it was just all machines before, by definition, there is no learning going on. And now we have this interesting question where machines are starting to learn. Well, that’s a new scenario. So all of this get wrapped up into the first idea for today, which is look, a learning curve. It has traditionally meant a human learning curve, but it now may mean a sort of digital learning curve. Okay. But the definition for a learning curve ultimately is a graphical representation of the relationship between proficiency and experience. Okay, fine. Then we move more into business because in the 1920s, 1930s, the aviation industry in particular, actually it was, the story goes, at an Air Force base in Ohio, the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. They basically noticed this. This was in the middle of World War II. They were making tens of thousands of aircraft. And I think it was a general or somebody, but then eventually a guy named Theodore Paul Wright did a study and he said, look, there appears to be an industrial learning effect, an industrial learning curve, in that the production cost for making an airplane seems to decrease by 20% every time we double the number of airplanes. And it doesn’t have to be tens of thousands. If they make one airplane and then they double to two airplanes, the second one was 20% cheaper. And then when they go to two to four, it was 20% cheaper again. And when they went from four to eight, it was 20% cheaper again. So what got people really excited was not just that you could get smarter, there was a learning curve, a learning effect. but it appeared to be consistent where you could hit 20%, 20%, 20%, 20%. And it’s suddenly like, that can really add up. That could be a, is that a competitive advantage if you’re always getting cheaper than your competitor? And it sort of started in aircraft. It started in aviation. It started basically in labor intensive, complex manufacturing. That’s when there was a lot of room for people to learn and get better. If it’s something really simple, like making a table, you can get better, you can get cheaper, you can get faster, but you’re not going to get that much cheaper and faster because it’s not that complicated. You’ll capture them, but if it’s something complicated and innovative like an airplane, you can keep capturing 20%, 20%, 20%, 20%. And out of this, McKinsey, I’m not McKinsey, BCG in particular started looking at lots and lots of industries. This was really in the 1966, 1968, early 70s. Bruce Henderson, they started looking at lots of manufacturing intensive industries to see if they could find the same effect. And sure enough, they did. And they called it the experience. also called the experience effect, which is really just an industrial version of the learning curve. And they showed that you could see this between 10 and probably 30% per doubling of production as a cost savings, but often it was about being faster. And that got the strategy people very, very excited. One of the reasons that got them excited was, it’s the same reason that people get excited about compounding. Making 20% more on your money this year is exciting. Making 20% the next year and the next year and the next year and the next year. When you get consistent increases like that, you get an exponential curve, which is compounding wealth, that’s Warren Buffett, everyone gets excited about. Well, this is the same kind of idea for a strategy. If I can get 20% and cheaper, and then next year, whatever the number is, I’m 20% cheaper again, and I’m 20% cheaper again, you can get an exponential decrease in your cost structure. So that’s what got people really excited that this could be a really powerful effect, same way people get excited about compounding. And BCG and a lot of these other companies, they really kind of took this too far. where, well, I’ll give you that explanation in a minute, but they kind of went a little gaga over this idea. It turns out it wasn’t really true, but you can look at something like the Model T, you can look at aircraft, and you’re gonna see a graphic just like the one I put in the show notes of this stepping down of marginal costs of creating a plane or a car with every increasing production. And that’s what people always talk about as the experience effect that, you know, manufacturing intensive complicated products can really, if you’re good at it and it’s got a high price point, you can really drop your prices and devastate your competition, which is what a lot of consumer electronics companies did. Companies who went after the experience effect, like calculators, early electronic calculators did this. They jumped into an industry early that was just emerging electronic calculators. that had some degree of complexity and they drove the experience curve so sharply that it wiped out their competitors in a couple years because suddenly they were 50%, 80% cheaper. So it can be a real strategic weapon in certain scenarios. And I would call that cost-based experience effect or cost-based rate of learning. Now, that’s sort of 1970s. the strategy stuff back then people got kind of nutty about this and I think it was incorrect what they were saying but basically there was an idea that wait a minute isn’t this a flywheel like listen like here’s the argument if my factory is bigger than another factory in terms of volume wouldn’t my factory be getting more experience faster than the other factory and therefore I should be moving along the experience curve faster, wouldn’t that make me more proficient, especially if I’m seeing one of these 20%, 20% experience curves? Wouldn’t that get me lower per unit costs faster than my smaller rival? Okay, and if I take these lower costs and I translate these into lower prices, wouldn’t that allow me to expand my market share versus my competitor because I’m cheaper than they are now? So I could use my cost advantage to get market share. Okay, but if I get more market share, wouldn’t that mean that I would have even greater experience because my volume would go up even higher? So, I should get more experience and therefore I should move even faster down the proficiency curve which would make me even cheaper again. So you start to get this argument that there’s a flywheel that you can get based on experience effects. And you can see it kind of mixes in the idea of economies of scale, market share, pricing, cost advantage, but anyways, I think consultants did pretty good business pitching this as a strategy. or if not a strategy, pitching it as a risk. Look, if your competitor’s doing this, you better be going after the experience effect yourself just to protect yourself. So there was this idea, now I don’t think that was actually true. And people don’t really talk about this anymore. For the most part, people don’t talk about the learning curve and the experience effect. They talk about it as a strategic weapon. but they don’t talk about it as sort of a dominant strategy that’s gonna get you any sort of real competitive advantage. Because it turns out it has a lot of limitations. For one, it doesn’t go on forever. Nothing goes on forever, especially when you’re arguing it’s an exponential effect. It turns out it’s a very cool effect. for certain scenarios that goes on for a while, but then it flatlines pretty quick. Ultimately, you can’t keep making things cheaper and cheaper, it doesn’t work. You can’t keep driving the cost of airplanes down, eventually it flatlines. There is a sort of limitation to this. The other problem is, if it’s not a higher priced item, there’s not an opportunity to drop the cost. If you’re making stuff for 10 bucks, you’re not going to drop it down to four bucks. There’s just not a lot of room. You need something like an aircraft that costs you tens of thousand dollars. You need something that’s complicated. The other problem is when you start trying to capture very aggressively these cost savings, these productivity gains, it generally comes at the price of your flexibility and your innovation. Because if you’re making airplanes and you are really going after this effect and you are streamlining everything and you are wriggling every little cent out of this, well that makes it very hard for you to create the next generation of airplanes because you’re very dependent on a very elaborate system you’ve built to be super efficient. So you kind of pay for this super efficiency with your flexibility and your ability problem. Anyways, the way BCG talks about this now, let’s say in the last 10 years, is they basically say this is a fairly decent strategic weapon to deploy into some types of industries and situations. And generally you’re looking for an industry with a stable demand that you can drive is fairly intense in terms of manufacturing and where the market is very cost sensitive, where if you can become cheaper, it really does pay off. And they call that sort of supply side experience curves. And one of the things that really has been taken apart in the last 60 years is they really did dig into the mechanics. of what is going on in these situations. And that’s actually really, really helpful. And let’s say you’ve got five or six different mechanics that can play out to make this experience effect show up in a company. Number one is just labor efficiency. Workers become more physically dexterous. They become mentally more confident. They spend less time hesitating, learning, experimenting. When they do things over and over, they learn shortcuts, they get faster, and that applies to people on assembly lines, it applies to employees, it applies to managers. So labor efficiency is a big part of what’s going on. Equipment, you sort of get better use of equipment. You start to exploit all the equipment you actually have. Things tend to get idle, less and less. You start to be able to justify more productive equipment. So you sort of win on the labor side, but you also win on sort of the equipment side over time. You start to get standardization and specialization. You know, as you do things over and over, you standardize certain parts, you specialize other, that tends to get you efficiency. And then within each of those, the methods tend to improve. You also tend to get sort of changes in the resource mix. You start changing your inputs over time. You get a little bit bang from that. But really the big one now is you get more data-driven learning. Everything is getting smarter. Things are getting automated. So there’s a lot of efficiencies that are getting pulled out of that. And that kind of brings us, I think, to where we are, which is, okay, so there’s the theory, there’s the history. How do you… Mix that in combine that with digital businesses, which is Really the question I’ve been thinking about for two years is what does it mean to have rate of learning within a business? And I’ll just give you my so what I think there’s three types and I’ve written this in my books for those of you For a credit, you know, I think and this is not my thinking a lot of this part is BCG that You know, there is cost focused rate of learning which is what we’ve been talking about, the Model T Fords, the aviation. There is product focused rate of learning where I’ll put these charts in the slides, I’m sorry, in the show notes. This is more, it’s not about your product that’s getting cheaper, it’s about being good at jumping to the next product, which is what Steve Jobs was so good at. And these are BCG arguments basically. But you basically, The skill that your company is learning is not just making your existing product cheaper and more efficient and better performance, which is cost-focused rate of learning, but you’re also learning how to identify the next thing and jump to it. So that’s iPod, iPad, iPad, iPhone, and so on. And then the third one is data-driven rate of learning, which is where it’s really the algorithms that are learning, not the humans. So everything I talked about with Ford and aviation, that was really about humans learning. This is more about the fact that machines are learning, the software is learning. So we had talked about this idea that, learning at the speed of algorithms, where when prices change on Walmart’s website, the Amazon… Computers know that immediately and they can adjust their own prices on the Amazon website in real time If I were to put my little books up on my web page and sell them for three bucks Amazon would know that and they would actually say that violates the terms of publishing on Amazon, which is true You have to give them the lowest price So they’d say hey, that’s three dollars and you’re selling it on Amazon for four or whatever is so That’s sort of algorithmic learning. Okay, so we start to combine rate of learning as an idea with digital. I think we get those three buckets. I think that explains most of what we’re looking at. And then I start to integrate that in with my own sort of levels of competition. And as mentioned, it’s part of tactics, it’s part of digital operating basics. The one, the two places I think it matters, and here’s the so what for today’s talk, is it shows up in the Smile Digital Marathon under Rate of Learning and Adaptation, which is one of the three concepts for today. And we can see this in some companies where they are so good at learning that they’re pulling ahead of competitors and sort of leaving them far behind, which is what I look for, that sort of marathon-like effect. And we can see this in a company like Shein, which is getting so fast at learning what customers want and what they don’t and what the fashion trends are in each city of the world. You know, that’s… kind of what they focused on early on and they’ve pulled so far ahead of other companies that they pretty much disappeared on the horizon. So sometimes that can become a real advantage. But the question I’ve been struggling with is, okay, when does rate of learning become a competitive advantage? Not a digital marathon. not an essential operating activity, not part of the digital operating basics, when does it rise to the level of a moat? That being fast at learning basically shuts down your competitors. And that’s kind of the question I’ve been struggling with for a long time. And that brings me to the third concept for today, which is if you look at my list of competitive advantages, On the right side, those are the cost and supply-based competitive advantages. On the left side, it’s the demand and revenue side ones. And up under CA7, you will see rate of learning and process cost advantage. So I think there are a couple scenarios. I think rate of learning is absolutely essential in the digital operating basics. I think it can become a moat, I’m sorry, a marathon. on a fairly regular basis, we do see that, especially when you start talking about algorithms, learning at the speed of algorithms. But this idea of when does it actually become a moat? And that’s basically my answer to that question, is rate of learning and process cost advantage. I’m putting this as mostly a cost advantage. And we can look at the three types I just mentioned. We can look at cost focused rate of learning. We can look at product focused rate of learning, and we can look at algorithming. And in the first category, I think the example to look at is Amazon. I think Amazon is an example of a company that has shown tremendous rate of learning through its operations that is effectively impossible to replicate. And that’s really, to me, the difference between, hey, this is an important operating activity, to hey, it’s a competitive advantage. When it’s a competitive advantage, it means your competitors can’t do it. for some reason they can’t replicate what you’re doing. And that can be from complexity. It can be that there’s nothing written down or transferable. It could be that the processes are just closely guarded and hidden by the company. But what we’re really looking for is we’re looking for processes and culture that is for all effective purposes impossible. to replicate such that they are always learning faster than you are and that is showing up in the costs. That’s where the rubber hits the road. Now, this is actually, and I think Hamilton Helmer, for those of you who follow him, the Seven Powers guy, he talks about something similar but he uses different language than that of you and he talks about, I would point to Amazon as a digital company that has a rate of learning mode. because of the complexity, because of the obscurity, the lack of transparency. There’s no gigantic book you can get from Amazon that if you followed that book, you could achieve their sort of cost structure and rate of learning. It’s too opaque. He talks about something similar with Toyota. He calls it process cost advantages, where Toyota is incredibly, which is very complicated, cars, things like that. They’re incredibly fast and they’re hyper efficient and nobody’s been able to copy it because it’s not like there’s a book. It’s just thousands and thousands of little adjustments that have been made by the people over 20 to 30 years that result in this. It’s this small accumulation of lots of little things that result. in their culture and systems that let them learn and capture cost savings faster than anyone else. So if we were talking about automotive, we would call this a process cost advantage. But when we look at a company like Amazon, I think the right terms are rate of learning advantage. Because that’s really, I mean, they’re not pumping out cars on assembly nines. They’re adjusting to the market so quickly. And basically no one can copy it. So that would be sort of One where I think we could see that I would point to. I think Amazon is an example of cost focused rate of learning. And what would we look for? Well, Helmer has some good factors he looks at for companies like Ford. He talks about processes with high complexity, very complicated logistics chains. Well, we can see that in Amazon too, their warehouses. The process improvements. that resulted in this situation are very opaque. They’re not written down. It’s just organizational knowledge that is tacit rather than explicit. The process improvements are mostly embedded within people, its culture, its daily activities. And the net-net of all of this is from a sustained evolution over time. Thousands of little changes over decades, that’s how you get it. So he’d call that process cost, I’d call it the rate of learning. And I’d point to Amazon as an example of when I think this really is a moat. If we move to the next type of rate of learning, which was product focused rate of learning, that’s Steve Jobs. That’s when I would point to Tencent. I think Tencent, I mean, they are basically like Apple under Steve Jobs, but not Apple under Tim Cook. Tencent rolls out new products so fast. And about every 18 months, they absolutely knock one over the fence. You know, QQ was their messenger, then they go into music, then they go into gaming, then they go into WeChat, then they go into WeChat Pay, then they went into, what are they in now? WeChat mini programs, now they’re going into search engines, then they’re in music video, and then they’re in, I mean, they are… I mean, arguably better than Steve Jobs. And I think that is absolutely a type of rate of learning that they are deeply tied into the ecosystem of mostly digital China, and they can identify what’s next and capture it very, very quickly. And they’ve been doing that for 23 years now. So that would be my number two product focus rate of learning. I think Tencent is the example. And I think that’s overwhelmingly about organization and culture. I don’t think that’s about processes. I think that’s organization and culture. And the third, so there’s two examples. And the third one, I don’t have a company, but I’m keeping an eye out for algorithmic learning. Has a company sort of put their software to such an advanced level that it can learn at a level that can’t be replicated by their competitors? That would be a moat. in algorithmic learning. I haven’t found that yet, but I’m sort of keeping an eye out for that third scenario. But I think we can look at Amazon in the digital world and Toyota in the production world as an example of sort of cost focused rate of learning. I think we can look at Tencent and to some degree, Apple under Steve Jobs as product focused rate of learning. And then algorithmic learning is sort of the next one that hopefully will show up sometime soon. And as we see, you know, this shift from humans using equipment, which was the aviation picture, to humans plus basically machine learning using equipment, I think this whole sector is going to become incredibly important. But this is why I’ve been struggling to take this apart for so long, because I think this is actually going to be incredibly important going forward. I mean, that’s kind of what machine learning does, right? It’s right in the title, deep learning, machine learning. It’s in the title of the term or in the phrase. So I think it’s a big deal. And the key question is the one I’m struggling with is at what point does it become a moat? Okay, so there’s two to three examples right there. And I think that is it for the content for today. That was kind of a lot. You know, the three concepts just to reiterate. rate of learning and experience effect, that sort of old school economic thinking from the 30s to the, really the 80s. Then there’s rate of learning and adaptation as a digital marathon, the L in smile. And then there’s rate of learning and process cost advantages as a moat, which is CA7. And those are listed in the show notes along with the slides that I’ve been mentioning. But I think that’s good for content for today. As for me, I’m in Tbilisi, Georgia. I just got in a couple days ago, I’m back on the road. And I’m really just stopping over for four days and then I’m heading to Istanbul on Sunday, where I think I’ll probably be there several weeks. But I’d always kind of wanted to go to Georgia because I kept hearing about it and it was sort of on the way. I said, oh, we’ll stop over for a couple days. It’s really a nice place. Like, it’s very hard to put your finger on. why it’s so nice or maybe I just can’t do it. Because there aren’t a huge number of sites in Tbilisi. There’s not a ton of things to do in the city. But it is just such a pleasant place to be. It’s sunny, it’s so green. I mean, there’s nature everywhere. You know, and there’s farms and animals and horses and berries and woods and churches on the hilltops and I mean, and rivers. I mean, it’s just. Walking around it’s just such a pleasant place to be it sort of puts me in a good literally within five minutes of walking out Everyone I just I’m in a good mood and In this cafes everywhere and you can sit and I’m finishing up my my fourth motes and marathons book. Hopefully this week So that’ll be out and yeah, it’s surprising So plus the food is fantastic like that seems to be what everyone agrees upon the food is great like it’s cheese and bread which is which is really problematic for a guy like me because I’m on a low carb diet and that’s just been blown out of the water. Like it’s everything’s cheese and everything’s bread and it’s all really, really good. So yeah, I mean, I can’t recommend it highly enough. Like there’s not a huge amount to do. Like it’s not, you know, it’s not like going to London or Rome, but man, is it a pleasant and nice place to be. So I’m gonna be here. I’m gonna go out to the… out of the city in the next day, maybe go up to sort of the monasteries and up into the hills and yeah, it’s a really beautiful place. Anyways, and then it’s off to Istanbul, so I’m having a pretty good week. So that’s it for me. I hope everyone is doing well. Thank you for listening and I’ll talk to you again next week. Bye bye.

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.