This week’s podcast is about how to apply DCF in valuations of digital companies.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

For the tennis ball story, here are the slides.

For DCF, here is my approach:

Standard thinking on DCF:

–—-

Related articles:

- Valuation Like Warren Buffett in 1 Slide (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- An Intro to Digital Valuation (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Valuation: Digital

- Discounted Cash Flow

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

———-

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

—–transcription Below

:

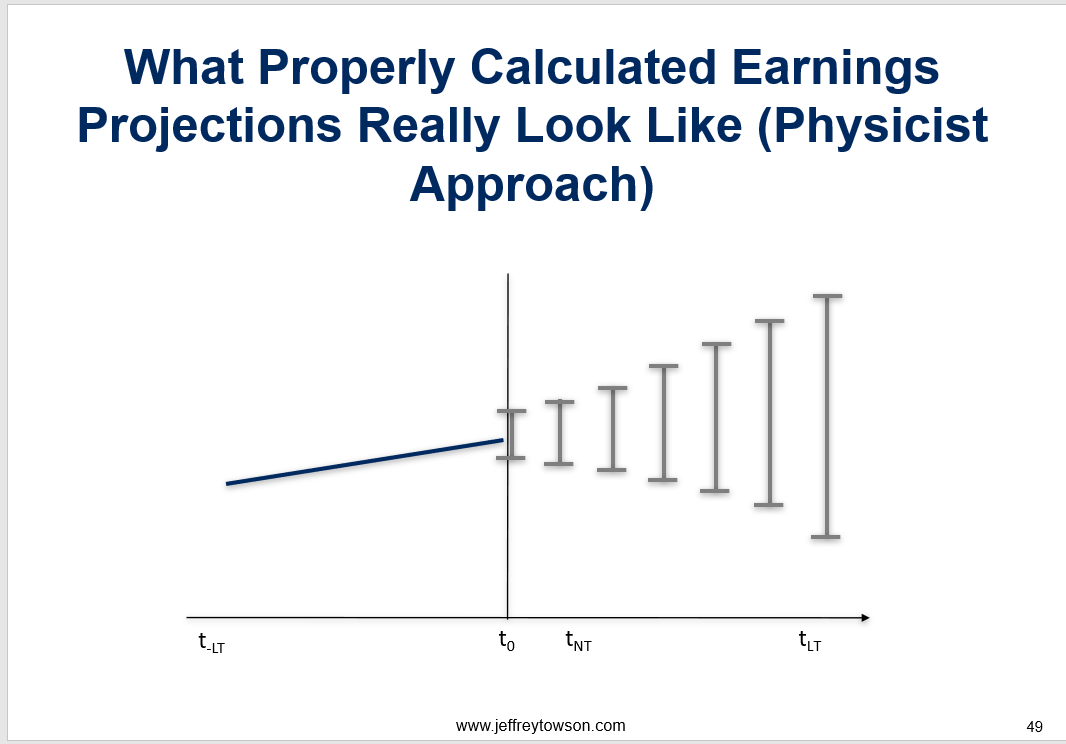

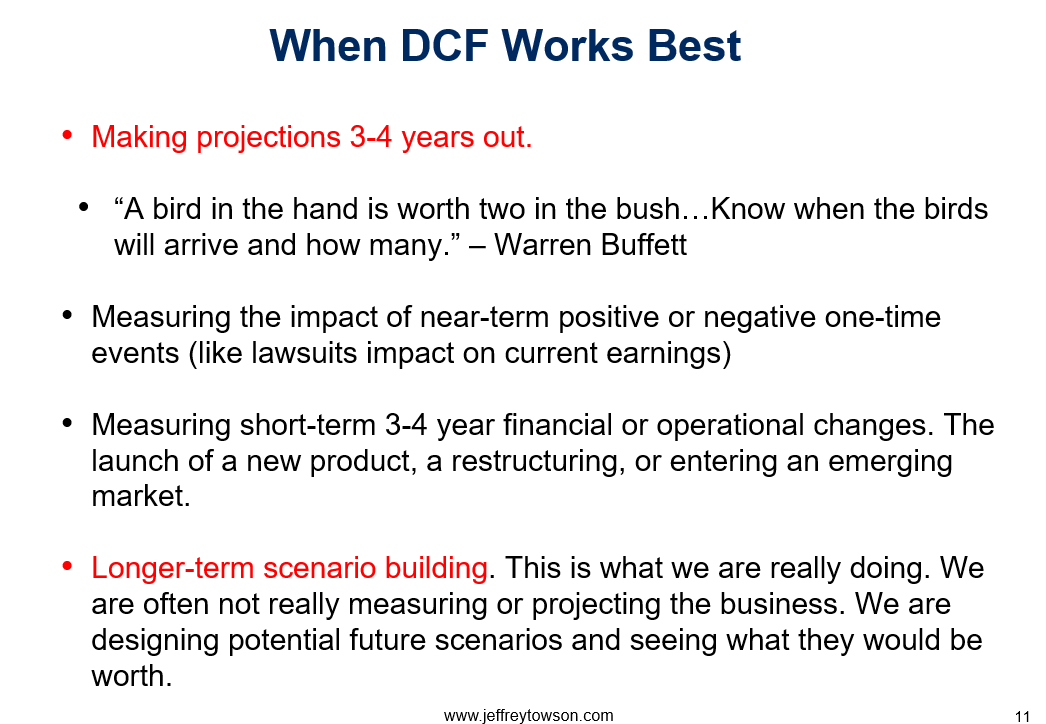

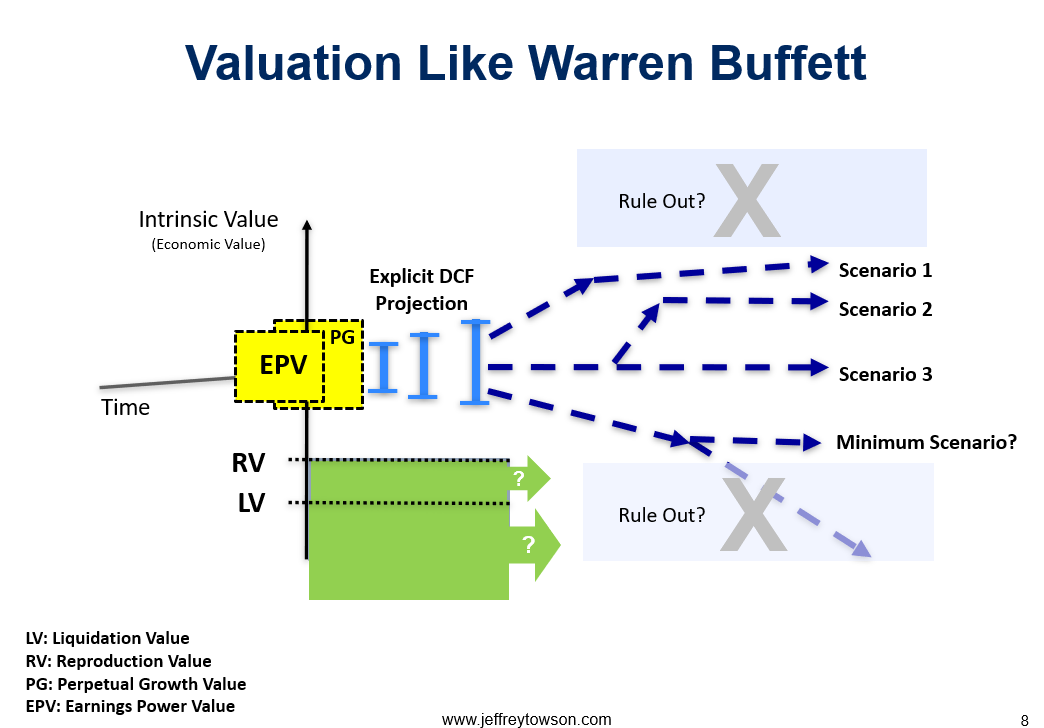

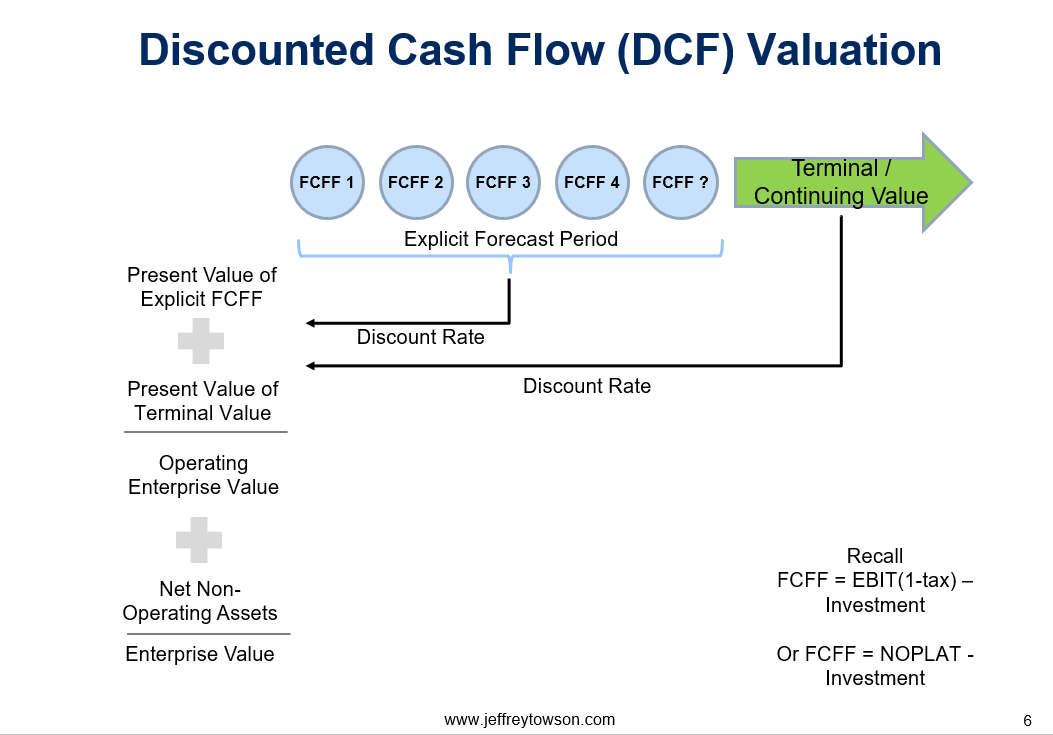

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Asia Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, why discounted cash flow sucks for digital valuation. So I’m shifting gears a little bit. 100 podcasts in the bank in terms of digital strategy, lots of frameworks, a book coming out on all of that. Actually, it’s going to be five sort of volumes together that form one sort of like super book. But I want to talk about the valuation side. I mean, valuation falls out of future performance. What’s going to happen next in strategy is kind of how you get a sense of that if you can. So I’m going to not do too much on this, but I want to really start to lay out some frameworks for that. So we’ll start with discounted cash flow, which is the go-to method for valuation, which I think is half good and half sucks and is used incorrectly a lot. I’ll give you my take on that and how I do what I call digital valuation, which is different than sort of traditional Hey, let’s look at factories and stuff. So that will be the topic for today now for those of you who are subscribers I was a little bit off my game last week. I kind of had a debilitating migraine It’s really hard to write when you have a migraine I I don’t get them often but what every two years I get completely taken out for a couple days and I have to kind Of hide in a darkened room. It’s really quite awful Anyway, so I got taken out, but I’m sort of back. So anyways, lots of information coming your way in the next day. Specifically, you’re gonna look at snowflake and cloud, which is kind of the other, that evaluation is kind of where my brain is right now, where I think that’s kind of the next big thing I’m trying to take apart. So that’s on the way. And let’s see, for those of you who aren’t subscribers, you can go over to jefftausen.com, sign up their free 30-day trial, try it out, see what you think. And standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information presented by me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions may be incorrect, no longer relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Now the concepts for today, every one of these talks goes under the concept library. The two concepts for today are valuation, which is under there, and discounted cash flow. So pretty basic. If you go to the concept library, you’ll find both of those there. Now, I haven’t done too much on valuation thus far. I did do a note for subscribers a couple of months ago called Valuation Like Warren Buffett. And I mean, I actually teach this in China. I’ve taught it a bit here in Thailand, which is, you know, how do you do valuation if I take away your Excel spreadsheet? and I just give you a pen and a piece of paper and a basic calculator. And that’s kind of how the course is designed. You have to figure out what a company’s worth without doing any of that Excel stuff. It’s a really good skill to have. And I think that’s how he does it. I don’t actually even think he uses a calculator. I think he just uses a pen and a piece of paper. But there is a slide on that. I also did something on private market value by Mario Gabelli. That’s kind of a different approach. So there’s. Two things in there, I’ll put links in the show notes to both of those previous articles. But today I’ll go sort of briefly through the basics of discounted cashflow, which I think most people know. And then I’ll basically tell you why I think it’s 50% wrong, 50% not used correctly, and why it doesn’t work for digital. So I’m gonna kinda tell you what I think is wrong. But I’ll also give you the standard approaches by McKinsey, by… Professor Demodaran at NYU, the valuation guru. I’ll give you some of that information too and put some information in the notes about that. Okay, so I guess the first bit is, standard discounted cashflow. You know, the basics, I’ll put a slide in the show notes. If you’re looking in iTunes or whatever, you gotta click over to my webpage. The slides don’t show up there. Click on the link, go to my webpage, where you can play the podcast there as well. You’ll see the slides there. But okay, basic slide, you know, projecting out cash flow after CapEx, after taxes, all of that, within an explicit forecast period. Can be three years, five years, eight years. You do that certain number of years, then you put a terminal continuing value at your eight, at your 10, at your five, whatever, which is kind of a baseline thing. You discount all of those numbers back to present value. That basically gets you an enterprise value for the operating assets, not the financial assets, just the operating assets. You can then add back the non-operating assets, which will be financial, and that will get you an overall enterprise value. That’s not a great description, me describing a slide, but I think people know that. Okay, so why is this so commonly used? Now here’s Professor Demodarin, I think I’m saying his name, right? You know, this is his notes on, you know, he will say the value of an asset is the present value of the expected cash flows on the asset. Direct quote. Fine, so it’s basically what I described, but we’re looking at operating assets most of the time, and we can kind of do cash flows tied to assets, discount them back to the present. Now, you could mix that together with financial assets or other type of assets. I prefer to look at just operating assets because that’s the operating entity of the company. The philosophical basis, according to a professor, every asset has an intrinsic value that can be estimated based on. its characteristics in terms of cash flows, growth, and risk. That’s the key issue and this is where I start to disagree. The cash flow, its intrinsic value follows from cash flow, growth, and risk. Cash flow I get, growth I get, risk I think is a made-up term. I don’t think it exists. What do you need to do the calculation? You need to be able to predict the life of the asset. you need to predict the cash flows during the life of the asset, and then you need the discount to apply to these cash flows to get to present value. And it’s usually the discount rate where people start to factor in growth. Here’s a, I’m sorry, the discount rate is where you factor in risk. Here’s the risk adjusted discount rate, capital asset pricing model, all of that. I think that’s all nonsense as well. We’ll get into that in a minute. What are the advantages of the discounted cash flow model? It lets you think about the value of the business as an operating entity. And then stocks and debts and other things are just claims on that value. It forces you to think about the underlying characteristics of the firm and understand it. It is largely a scientific method. So we don’t care about what the market thinks. We don’t care about what it sells for. That’s all basic. In terms of definition, This is arguably the best definition of value. It’s not the best way to calculate it, but you could argue this is the most accurate definition. It’s the most logical definition of value. but you immediately run into problems. Because by definition, we’re incorporating the future into the value and the future is inherently unknown. So this very accurate logical definition is impossible to measure. If an asteroid hits the earth tomorrow, those cash flows were wrong. How do you incorporate an unknown future into current value? If you’re already discounting the future, then why would you ever need to change the value in the future? Because you’ve obviously looked at the future, discounted it appropriately. We’ve incorporated the future into the value we see today, but obviously the values we calculate change all the time. So we’re not doing a very good job of incorporating the future. It is impossible to measure or estimate discounted cashflow accurately. It requires very explicit inputs and information, much more than other valuation approaches like earnings power value, asset value. It requires a projection until the end of time, which is ludicrous. It requires a time-specific projection. That’s actually kind of interesting. The way people set up their spreadsheets, here’s year one, here’s year two, here’s year three, you’re telling someone what the revenue’s gonna be in year five. That’s actually making two estimations. One, what will the revenue be? And two, when will it be? It’s a very different question if I ask you, will I be 150 pounds between years five and eight from now? That’s an estimate of value, but not an estimate of time. That’s a different question than saying, what will I weigh on January 1st, 2018? Or I guess 2025? Predicting what some will be will add a moment in time is dramatically more difficult, but all Excel spreadsheets That’s what everyone does year one year two year three Okay, when does discounted cash flow work well? In my opinion, it works well for making projections three to four years in the future, but not beyond that. I’ll explain why that is. And I think it works well for long-term scenario building. I’ll go into that. Okay, so that’s Professor Demaderand. Here’s the McKinsey version of discounted cash flow. This is from their book, Valuation, which is a big textbook by McKinsey. It’s quite good. It’s really a high quality set of models for doing valuation. I agree with about 70% of it. A professor, I maybe agree with 50% of what he says. Um, not that he cares at all or McKinsey cares at all. I’m just telling you where I land. Okay. McKinsey discounted cashflow. They talk about enterprise discounted cashflow. Here’s a quote. The enterprise DCF model discounts free cashflow. meaning the cashflow available to all investors, equity holders, debt holders, and any other non-equity investors at the weighted average cost of capital, meaning the blended cost of capital for all investor capital. The debt and other non-equity claims on cashflow are subtracted from the enterprise value to determine the equity value. So they’re basically making it. a distinct, they’re kind of closer to the NYU guy. We’re gonna look at the enterprise value regardless of who owns it. This is what the operating asset’s worth. And then you can piece apart the pie to the equity holders and the debt holders. And they’re making that distinction because you can do equity valuation models directly, which I don’t think is a good idea. Going on, McKinsey, valuing a company’s equity using enterprise discounted cashflow is a four-part process. Value the company’s operations by discounting free cash flow at the weighted average cost of capital. Identify and value non-operating assets, excess cash, marketable securities, non-consolidated subs, blah blah blah, separate them. Identify the value of all debt and non-equity claims, subtract all of that. So same approach, but the language that is different here, so in the sense they’re very similar to NYU guy. I’m using that phrase to avoid butchering his name. But he’s looking at risk adjusted discount rate. They’re talking about discounting the cash flow at the weighted average cost of capital, but they’re really talking about the capital asset pricing model, which means putting in the beta. They’re incorporating, they’re both incorporating risk into the discount rate, which I think is a bad idea. Anyways, those are their basic definitions. I’m gonna put those slides, their summaries in the show notes, which are on my webpage. So you can see how they’ve specifically defined it and their language. I think that’s how most people do it. I think that’s how you’re taught how to do it. I think that’s how everyone who goes into investment banking does it. I don’t think it’s great. I don’t think it works for digital stuff very well. So that’s sort of teeing up. the common approach, now I’ll tell you kind of why I disagree. Okay, now I like to do an exercise in class which is basically tell me what I weigh. And I literally ask the students, how much do I weigh? So if you were going to calculate, well first you have to decide, well what do you mean weigh? Are we talking the weight at this exact moment in time? Are we talking about my average weight? Average weight in a day? Average weight in a year? I mean, what do you mean? So I say, okay, what do you… What is my average weight over the course of a year? And what do you think my average weight will be four years from now? That’s the question. Okay. Well, the first thing we have to think about is, well, we could measure it, and I let them do anything they want. What do you want me to do? And they say, oh, we’ll go get a scale. Okay, I’ll stand on a scale. Scale is quite a good way to measure weight. I mean, that’s its whole purpose. Fine. Do you measure it once? Well, no, no, we’d have to measure it multiple times. Okay, because I might weigh more in the morning than I do in the evening. Little bit, drink some water, whatever. Okay, so maybe you do multiple measurements in a day. What about over the month? Okay, we’d probably do multiple measurements over, we’d probably put you on that scale. several times a day, maybe several times a week, several times a month, we get a bunch of values and then we do an average, add them all up, divide them by the number, that gets you an average. So we have a measurement, we have a calculation, and then we sort of get the average weight and you try and project forward in whatever way. Okay, if you actually do that on paper, you’re gonna have to have two numbers. And this is where I dislike finance and I dislike business because I came out of a physics background and I was trained. We, you never saw one number. It was always two numbers for everything. What is the speed of light plus or minus how much? What is the speed of that taxi going down the street? 45 miles an hour plus or minus three miles per hour. you always had an estimate of the value and you had an estimate of the uncertainty in your conclusion, always. So it was always plus or minus, you try and get to a 95% confidence interval. And actually calculating uncertainties is more complicated than calculating the value. Okay, so we go back to the weight question again, and you say, okay, what’s the uncertainty in the measurement process? Does the scale measure me? Now I weigh about 140 pounds. Does the scale measure me to 140.237 pounds? Oh no, I mean, it’s got a little dial. It doesn’t read it that accurately. Okay. So my scale only probably measures to 140.5 versus 141. I mean, it’s only got so many digits showing. And then two, there’s gonna be some uncertainty in the machine itself. So you could probably estimate an uncertainty in a basic scale, a bathroom scale of 140 plus or minus.5 pounds. That’s probably about right. Fine, you do a bunch of those. You’ve got a bunch of measurements of me. 141 point plus or minus.5, 139 plus or minus.5 pounds. You’ve got a bunch of these and then you add them together and you divide them by the number, you get the average. However, if you take two numbers with uncertainties, 140 plus or minus five pounds, and you combine that with 141 plus or minus five pounds, and you divide it by two, the uncertainties add up. The answer, what did I say? I said 140, and let’s say 142. So 140 pounds plus or minus 0.5, 142 plus or minus 0.5, the average would be 141, but the uncertainties add. it’s now 141 plus or minus one. Uncertainties compound. So the more numbers you add together, you start to increase the uncertainties. So there’s uncertainty in the measurement, the scale, there’s uncertainty in the calculations, and then you’ve got to ask, is there even uncertainty in the concept? Now in this case, weight is actually a pretty good concept. It’s a scientific concept. We can measure it explicitly, we can remeasure it. You know, it’s gravity to the center of the earth in this case. Weight is a fairly accurate concept to measure. So we have definitional, like concept uncertainty, calculation uncertainty, measurement uncertainty. If you do the calculation properly, you can probably get to the conclusion that Jeff weighs 140 pounds plus or minus two pounds in a given year. Basically between 138 and 142. That would be about as accurate a conclusion as you could draw. Anyone who comes to you and says, “‘Jeff weighs 140.5 pounds.” It’s like, wait, you’ve got it down to the 0.5, really? And where’s the uncertainty? Oh, no uncertainty, Jeff weighs 140.5. Mike, that’s just bad thinking. Now we see this all the time. Every year people will get up and say, “‘Well, what was China’s GDP growth?’ Well, China’s GDP growth this year was 6.4%. It’s like, really? You estimated the entire size of the entire economy, everybody doing everything, you put a number on it, you didn’t put any uncertainties at all, and you told me it to a decimal place? You can’t tell me my weight growth in one year to that specificity, but you’re telling me the entire economy grew? I mean, it’s just bad thinking. Anyway, so that’s sort of one exercise we do. And then I do another exercise, which is, okay, number two, what is my average happiness in a year? We just did weight, one concept. Let’s do another concept. What’s my happiness? Well, I don’t know. What is happiness? Kind of hard to know what happiness is. It’s not like weight where we can put a scale on the ground and measure a physical phenomenon. Happiness is kind of in my head. It’s not exactly a well-known idea. It’s kind of vague, kind of changes. It’s not externally determined. It could, I don’t know. Okay, so there’s a lot of uncertainty in the concept. You’re not gonna tell me my happiness to 140.5. you’re gonna start thinking about my happiness is high, low, medium. You’re not gonna get much more accurate than that. And then you’d have to get to the problem, okay, it’s a vague concept, a lot of uncertainty, how would we measure it? Well, there’s no way to measure it either, really. Well, you can, but it’s gonna be high uncertainty. And then we’re gonna add all those numbers together, so we’re gonna get a massive calculation uncertainty. My happiness is gonna be, hey, Jeff is somewhere between 80 and If the scale of happiness goes between zero and 200, Jeff’s between 100 and 150. You’re not gonna do better than that. It’s just, it’s a vague idea. Okay, so that’s kinda how I started. And then the question is, okay, we’re talking about intrinsic value of a company. Valuation. Is intrinsic value, economic value of a company more like measuring my weight or is it like measuring my happiness? It’s kind of both. Yes, there’s cash flow, so that’s logically consistent. So you could say that it’s a very good concept. It’s a very logical concept. So you could argue that the definitional uncertainty is quite low, it’s closer to weight. But when we talk about measuring it, we realize we’re trying to measure something in the future. Well, that’s got a huge measurement uncertainty. because the definition kind of bakes in things that are gonna happen in the future. There’s no way you can measure it accurately. I can measure cash flow accurately today. I can look at cash in the bank. Cash flow in two years, the measurement uncertainty is a bit high. The definition has some uncertainty baked into it. So that’s bad. And then unfortunately, everyone gets out their spreadsheets and they start putting in number after number after number into lots of cells in their spreadsheet. and they all start adding them together and they don’t calculate the uncertainties. And if they did, they’d realize once you add more than 10 numbers together and divide them, the uncertainties have compounded to such a ridiculous degree that you’re, people will tell you this, the revenue in year one is 100, the revenue in year two is 105, the revenue in year three is, let’s say 110. We subtract the cost. The operating profit in year one is 10. The operating profit in year two is 15. The operating profit in year three is 20. Not really. If you do it with the uncertainties, what you will get is the operating profit in year one is 10 plus or minus four. The operating profit in year two is 15 plus or minus six. The operating profit in year three is 20 plus or minus 15. the operating profit in year four, 25, plus or minus 20. The calculation uncertainties grow exponentially. Once you get to year three or four, the numbers are almost entirely meaningless if you’re projecting forward and doing lots of calculations. So that’s kind of my first take on that. I will put two slides in the show notes that basically show you how people typically. do a cash flow projection into the future without the uncertainties, but if you put them in, you’ll see a picture like I’ve attached, which is basically an exploding spectrum of possibilities after year three, after year four. So it’s pretty meaningless if you try and do discounted cash flow more than three or four years, almost always. Look at the two slides in the show notes of what people think they’re calculating versus what they’re actually calculating. I mean, pause the thing, look at them briefly, you’ll get what I’m talking about. Then come back. And this is why I don’t like the risk adjusted discount rate, which is why I never use it. You can actually try to project your cash flows forward and it’s logical. And if you do it with uncertainties, you can actually get a fairly accurate estimation of what the future might look like. That’s closer to measuring weight. It’s just not as accurate as people think it is because they don’t do the uncertainties. But then they take that well thought out future projection of operating performance and they divide it by a risk adjusted discount rate. What is the risk adjusted discount rate? That’s mixing my weight with sunshine. It’s like saying I’m gonna spend a lot of time figuring out what Jeff’s weight is gonna be in three years and then I’m gonna divide it by Jeff’s happiness. And that’s my answer is weight over happiness. Because how do you risk adjust the future? Well, we think it’s high risk, so we’ll say 15%. Well, we don’t think it’s high risk, we’ll use 8%. That’s made up. So I don’t wanna take apart and dilute fairly well thought out performance projections with good uncertainties, and then divide them by some made up number called risk. That’s why I don’t do it. It’s weight divided by happiness. No, no, I’m just gonna ignore happiness. I’m just gonna focus on being accurate in weight calculations, that’s it. Okay, now, I’m gonna put some slides in the notes. Sorry, there’s a lot of slides for this one. This is a story I like to go through. We got three professionals. We have a physicist, we have a doctor, and we have an MBA, finance person. They all go up to the top of the roof of a building at Peking University. And on the top of the roof, there is a tennis ball machine that shoots tennis balls, right, when you practice tennis. And it’s pointed due west. It has a fixed velocity, elevation, and angle. It’s locked in there. And we ask all three professionals, we’re gonna fire the ball due west, onto campus where there’s buildings and shrubs and grass and trees and other things. My question for you is where does the ball stop rolling? How would you calculate this? Give me an answer. And I’ve put a little picture in the show notes of Peking University campus, if you’re curious, with an arrow on top of a building going due west over a courtyard with some trees and there’s other buildings. That would be the question. Now the physicist will bring back the following answer. They will start doing physics calculations. We look at the force, we look at the drag, we look at gravity. We look at other variables and we focus on the, like the predicted value plus the uncertainty in those values, because physicists are all about uncertainty. So are engineers. We might look at past data of other balls being launched off the, you know, the roof there. And we might do some test throws, test firings, but the physicists will come back with an answer like the following. We believe We are fairly confident that the ball will land at the following coordinates. On the X axis, if you put an X and a Y axis across the campus map, on the X axis, we think it will land at 150 meters plus or minus 30 meters. So we think it’s gonna land in an area between 120 meters and 180 meters. On the Y axis, we think it will land at 120 meters plus or minus 15 meters. We’re gonna get much less variability in the Y axis because we’re firing due West, which is kind of along the X axis. So overall, we’re gonna basically draw you a square between 120 and 180 meters on the X axis and between 105 meters and 135 meters on the Y axis. We are 95% confident it will stop rolling within that square. we think the time when it stops rolling will be 15 seconds plus or minus two seconds. That would be a typical physics answer. Okay. And I’ve put a picture in the show notes of how that looks. It’s basically a square across campus. Fine. Now the doctor comes. Doctor comes back and says, well, what do doctors do? Doctors look at you, they ask you a bunch of questions, and they list, they make a list of possible diagnosis you may have. Well, Jeff has come into the ER, his stomach hurts. It could be he had some bad food. It could be, I don’t know, gastritis. It could be, it could be a lot of things. You usually have, let’s say 10, 15 things. And then you would often run tests to try and decide which of them on the list. But what you typically focus on is ruling out the worst case. You’re not actually looking, you kind of know what the most common thing is gonna be. Look, it’s probably just he ate some bad food. That’s most likely what it is. But that’s not really your job as a doctor first. Your job as a doctor first is to make sure it’s not something really bad, that if you miss it, Jeff’s in trouble. So the first thing they do is say, okay, let’s put you up to the EKG and take some blood tests and rule out that make sure this isn’t a heart attack. It’s in the chest area, you’re of a certain age. Look, it’s probably not likely, but we need to rule out heart attack. So then the doctor will come back to you. So they do diagnosis by exclusion. Let’s figure out what it’s not. And let’s figure out what the bad case first. So the doctor would come back to you and the doctor’s not gonna tell you where the ball lands. The doctor’s gonna come back and say, look, we’ve done some tests. We are very, very confident the ball will not land to the east of the building. We’re firing it to the west. We are very confident it’s not gonna end up to the east. We are also very confident that it will not land north or south beyond a certain point because it’s mostly going west. We are gonna rule out 75% of the map immediately. And then we’re gonna focus on the area that’s left. Oh, and we don’t have an estimate for the future at the timing at all. We don’t know. But we’re gonna basically rule out a big area. So I’ve put the same map in the slides and I’ve basically X’d out a big portion of the map. That’s kind of what doctors do. Okay, last case. The doctor, the MBA comes in, the finance person. He or she pulls out a spreadsheet. Oh look, it’s Excel. It’s full of numbers, it’s full of calculations. There’s no uncertainties measured in any way, by the way. He says, we have made a bunch of columns projecting forward where the ball will go at each ten second interval. column one, 10 seconds, column two, 20 seconds, column three, 30 seconds, and we are projecting where it’s gonna be. We also looked at comparable throws. We looked at throws off other buildings. We did comparisons. We projected a final position, and then we did some sensitivity analysis. Overall, we feel the ball will stop at the following coordinates. We think it will be at X. X will equal 150.5 meters. it will be why 120.25 meters and it will stop rolling at 15.43 seconds. That is typically how MBAs do things. Now you should be shaking your head and saying that’s idiotic. Like it’s stupid. You instinctively know that’s not possible. Nobody could predict where a tennis ball is going to land shot off a building. at 150.5 meters, 120.25 meters, and 15.43 seconds. Oh, and by the way, no uncertainties. It’s ludicrous, and you know that because you have a sense for the real world that it can’t be done. It’s not like the MBA is right or wrong. It’s like, that’s just idiotic. But if you look at typical MBA projections of cashflow, that’s exactly what they’re doing. They’re projecting forward with a straight line. Here’s what… the revenue costs operating cash flow are going to be your one, your two, your three, all the way up to your 10. No uncertainties, very specific, and then we’re going to discount it back. It’s nutty. And then we’re going to discount that ludicrously specific projection with a made up happiness number of this feels risky. So you already had bad analysis and then you’re mixing it with more bad analysis and the whole thing is usually meaningless. That’s why I basically don’t do discounted cash flows beyond three to four years. I don’t use risk adjusted anything. I focus on doing discounted cash flows for three to four years with a lot of focus on the uncertainty. Then I spend a decent amount of time trying to rule out future scenarios like a doctor. Uh, I don’t think the value will be below this. I’m fairly confident. I don’t think the value can be above this. I’m fairly confident. So I’m ruling out areas. I’m doing a three to four years of explicit cash flows. I’m not talking risk adjusted anything. And within by doing that, I basically have sort of carved out a range for the future. Okay, I think the value could be in that range. It ain’t gonna be those numbers. And the explicit cash flow did pretty well. And then all I do is I am within that zone of potential futures, that range, I just map out three to four scenarios. I think maybe in three to five years, the company could look like this, like this, or like this. And then based on those, I do a discounted cash flow back from those. but I’m not projecting forward, I’m projecting, I’m sort of discounting back from a future I have described, but I’ve basically made it up. And that’s kind of how I do it. And if you look at the slides, I’ve put in one slide, which is sort of my one slide for valuation, the Warren Buffett one page valuation slide. And you can see on there how I’ve done it. Literally, you can see three to four years of explicit discounted cash flow. But with increasing uncertainty as you go forward to use two and three, I’ve ruled out certain areas like a doctor. And then within the range of potential futures, I’ve just mapped out three to four scenarios and then use discounted cashflow back from those to put a number on them. And that’s pretty much what I’m doing. And when you start doing digital, two things happen. Number one, the range of potential futures starts to get much wider. Projecting Coca-Cola, you can actually do it fairly accurately, but when you start talking about how Alibaba’s gonna move, software, it just moves faster. So thinking about the range of potential futures and ruling out scenarios is a better approach to a high uncertainty situation like software. The second thing that happens is you start to get more optionality. That approach I just gave you. That’s within a business we can kind of understand seeing it going forward. But then on top of that, you start to do options. If this new product or service by Didi, let’s say food delivery in Latin America, takes off, I wouldn’t put that in my core calculation, but I would put that as an option on top of that. If C Limited starts to really do well in the EU, I wouldn’t put that in the core calculation, but I’d put that as an option on top of that. So I’m sort of doing that. that approach I just laid out plus options stuck on top. And that’s kind of how I do digital valuation. Usually that’s most of what I’m doing. One other thing you can do, which I won’t go into today, is you can do expectations investing, which is Michael Malbison. I’ll talk about that at another point where you start to look at the stock price of a company and you use that to infer the expectations of the market and then you… try and predict where expectations may change. It’s kind of an interesting approach. I think about it like 5%. That’s like 5% of what I’m doing. I’m sort of doing 65% of what I’m doing is that core explicit cashflow, rule out scenarios, scenario building, discounting them back. And then let’s say 25% I’m doing optionality, 5% I’m doing sort of expectations investing. That’s usually what I’m doing. One last quote for you from Seth Klarman, the Bao Post Capital Guru. Quote, many investors insist on affixing exact values to their investments, seeking precision in an imprecise world, but business value cannot be precisely determined. The future is not predictable except within fairly wide boundaries. And you can literally see visually how I’ve done that on the graphic. I mean, there’s literally a future bounded, sort of showing where I think it begins and where it ends and what the range is. Okay, I think that’s all I wanted to cover for today. So digital valuation, how do I use discounted cash flow? I do explicit discount. Explicit DCF for three to four years from the current situation, but I don’t use risk adjusted anything. I just project the cash flows as accurately as I can with being very sensitive to the uncertainties of my calculations, the definition, and the measurement. I usually just discount them by the cost of capital across everyone the same. I don’t change it. And then I also do discounted cash flow when I have mapped out a future scenario three to five years in the that I have just sort of created in my head within the range of potential futures, then given that future, I can discount the cash flow from that back quite accurately and I can value that future because I’ve kind of defined it myself. But I don’t project forward 10 years ever because I don’t think it can be done. That’s my approach. The two concepts for today, which will be in the show notes and go under the concept library. valuation and discounted cash flow. And I think I’m really gonna build out this whole idea of digital valuation. How do you value software companies, data technology companies, AI companies? Because everything I just said requires you to have an understanding of where the company is going. What is the single biggest factor in my opinion that’s gonna change the future trajectory of a company and therefore its value? Competitive advantage. which is what I focus on, right? If you have a company with a strong competitive advantage, competitive defensibility in a digital situation, it’s gonna be far more predictable than anything else. Now there’s other things that could change the future, technology, government, politics, but that’s kind of the main factor I try to get my brain around. If I don’t feel like, if I don’t see real strong competitive defensibility in a company, a moat, my ability to project the future scenarios drops dramatically. I feel like I got nothing. I got nothing. I feel like I don’t know what to do. So that’s always my starting point is competitive advantage, look into the future, and then try and work out the valuation. Okay, I think that’s it. As for me, I’m getting ready to fly out of Bangkok in a couple days. I’m finishing up two classes right now, which has kind of been a bit of work. and flying to Berlin, giving a talk there. I was supposed to come right back to Thailand and do sort of the Phuket sandbox for two weeks, but there’s some visa issues. I spent like 10% of my time dealing with immigration here. It’s really getting annoying. Might be some problem. So I think probably I’m gonna end up getting stuck in Europe for about three weeks. So now my question is, what the heck am I gonna do in Europe for three weeks? That wasn’t really the plan. It’s kind of exciting. I’m like, okay, maybe go south because I don’t like to be cold. So I’m kind of looking for some places to go. A buddy of mine’s in the Ukraine. I was thinking of going over to Kiev and seeing him looking around Eastern Europe. I don’t spend much time there. Kind of like Croatia and maybe down to Greece, sort of stay on that side of Europe. I don’t know, if anyone has any ideas, let me know. I literally don’t, this happened in the last couple of days. And I’m like, I literally. don’t know what to do and I don’t want to move around. I want to kind of do like I usually like to stay in one place for a month and just enjoy myself, hit the gym, work as opposed to you know traveling around. So I’m kind of looking for a city to sit in for maybe two weeks. I’m thinking Belgrade, Budapest or maybe Kiev. I don’t know if anyone has any suggestions let me know. I literally don’t know what I’m doing as of eight days from now. Anyways that’s that. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope everyone’s staying safe. If you’re in Thailand, it looks like things are opening up. I think the movie theater is open this week, finally. I think the gyms open in a couple days. Almost out of this, hopefully. Anyways, that’s it for me. I hope everyone’s doing well. Bye-bye.