This week’s podcast is about Full Truck Alliance, a B2B marketplace platform for freight and cargo. There are a lot of lessons on the difficulties and complexities of matching, pricing and network effects for more complicated services.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

Questions for simple network effects:

- Local vs. regional vs. international network effects?

- Fast vs. slow network effects?

- Directionality of interactions (Facebook vs. Twitter)?

- Degree vs. value of connections?

- Minimum viable scale vs. asymptotic scale?

- What is congestion / saturation / degradation scale?

- Linear vs. exponential growth at different scales? For each user group.

Questions for complicated network effects:

- Less than truckload freight (LTL). This is about coordinating demand and locations for mobility. This is similar to carpooling in ride-sharing. The matching, pricing and network effects are more complicated.

- On-demand vs. synchronous vs. asynchronous. Matching, pricing and network effects are more complicated. Pricing can follow spot demand vs. scheduled.

- Cyclical and other fluctuations in both supply and demand. This impacts both prices and utilization.

- Route specific network effects. Need to balance supply and demand (and critical mass) on each route.

- Serial routes. Matching, pricing and arranging multiple routes in sequence. Much more complicated

- How does this compare with economies of scale in geographic density.

How FTA describes its flywheel.

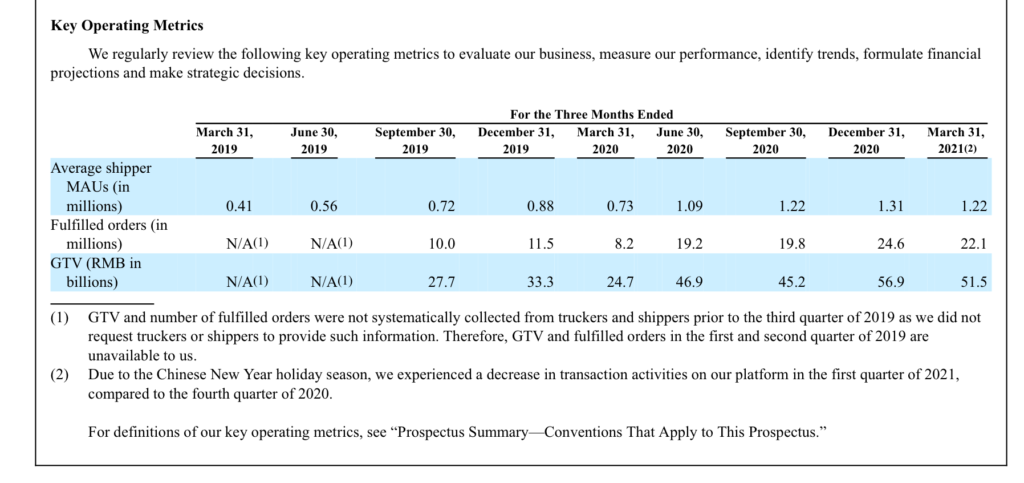

Numbers on FTA usage

–—–

Related articles:

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Network Effects – Simple

- Network Effects – Complicated

- Marketplaces for Services

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Full Truck Alliance

Photo by Zetong Li on Unsplash

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

——Transcription Below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, truck alliances fight to build complicated network effects. Now this is, you know, it’s a B2B company. It’s kind of like Uber Freight. It’s a, you know, connecting truckers with people who are placing shipments. And it’s in China. So it’s kind of the freight version of DD or Uber. In China, they’ve filed to go public so we can see their numbers. And I’ve been waiting for this for a long time. I’ve been following this company for years. So finally got a chance to go through that. The name is actually not Truck Alliance. It’s filed under full truck. Alliance. I’m not quite sure why that helps. I used to make fun of the name when it was just called Truck Alliance and then they you know they started going by Man Bang which is it sounds pretty good in Chinese but in English people pronounce it Man Bang which is which is pretty funny as well. So anyways, I don’t know what’s going on with the names of this company, but it’s kind of funny. Anyways, we’ll sort of go into that. And the main topic is at first glance, this is going to be like, oh, it’s like Uber, it’s like Didi, it’s another shared mobility type platform business model. And that is to some degree true at first pass, but then when you look into it, you realize that there’s a lot more going on with this type of network effect. and platform business model than we see. So you could almost say like, look, Uber and DD in terms of mobility, that’s simple network effects. This is a much more complicated version with a lot of interesting things to talk about. And they’re really kind of, I would say, struggling to pull this off. They’re making progress, they’re going, but it’s clearly not been an easy ride. I guess that’s a good word for it. Anyway, so I’ll go into sort of how to think about the sort of next level of complexity, almost maybe next generation network effects for sort of mobility. So I thought it was a good topic for that reason. So that will be the topic for today. Now let’s see, I’ve got a whole list of companies coming up. I’ve been buried writing a book, so I’m finally getting out of that. And there’s been a quite a few companies I’m going to be going through for those of you who are subscribers. Next on the list, Dingdong, which is, you know, in Chinese it’s meitai, which I think people know about. There’s some interesting AI driving electric vehicle companies, ponies coming up. It’s coming to call many core which I’ll go into and then we’ve got a couple IPOs in the near future Market curly out of South Korea Ken Jun, which is a recruitment website out of China and then Shima Laya Which is a podcasting so there’s got a whole I mean, it’s just it’s just one tech IPO after the other coming out of China Asia It’s getting kind of hard to keep up to tell you the truth Okay, so that will be the topic if your subscribers expect that to be coming shortly as well as I’m gonna send you some writing bit more on truck alliance because I think there’s it’s one of these companies I really get excited about because one it’s interesting but also there’s a lot of good conceptual stuff going on. So I like companies where you can speak to both the company and the concepts and then they go in both of the libraries on the web page concept library company library. Anyways that’s coming up. For those of you who aren’t subscribers feel free to go over to jefftausen.com you can sign up there free 30-day trial see how it goes join the group there’s a lot going on it’s fun Don’t miss out. Maybe there’s a great company up there you haven’t heard of that you should be paying attention to that you’re not. Maybe there is a company you’re following but there’s an aspect to it particularly with regards to strategy that you weren’t thinking about. Anyways, that will be that and with that, oh, I got to do the qualifier. Okay, hang on the standard claims qualification here and nothing in this podcast or my writing or the website is considered investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and expressed by me or guests may no longer be accurate or relevant. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the content. Okay, now first thing is always is there’s always a couple key concepts sort of learning goals for every talk and the two for today, well it’s really one, it’s just network effects but this idea of basic simple network effects versus more complicated ones. And this is actually something we see in in business after business. So much of the digital story has been about companies over the last 15 years doing the easy stuff first. You know e-commerce started with books. Why? Because books standardized, no experience aspect. And they kind of went from there to consumer electronics and appliances and other things. But it was only recently that they started to jump into the harder areas like groceries. And we see the same thing, let’s say in services where a lot of the initial services were like, let’s do commodity simple services like renting a hotel room. Well, that’s a little more differentiated. Let’s say book an airline ticket, get a ride. basic simple services and now companies are getting more into things like hire an accountant, hire a doctor. So again it’s the same idea but so much of the story has been about let’s just go with the easy stuff. And we can look at Uber and DD as the same story that a lot of the mobility story has been about, let’s do the easy stuff. You’re here, you need to get to the airport, that’s a ride within town, commodity, simple, anyone can do it. Everyone can use a ride and pretty much anyone with a car is good to go. You know, same thing, simple, largely standardized local services. We see that story over and over again and a lot of the theory, the concepts. are kind of based on the simple version. And then when you get into more complicated stuff, you realize, okay, there’s a lot going on here conceptually that I wasn’t thinking about. So that’ll be kind of the idea for the day, is like network effects, we’ve talked about them, I’ll review some of it, but we’ve been talking about simple versions of these, and I wanna go into sort of more complicated versions, and I think truck alliance is a great example of that. Second to that, I’ll point to economies of scale in geographic density. Um. Obviously, economies of scale we’ve talked about a lot, well, I’ve talked about a lot, and I’ve laid out four or five major types. That’s all in the concept library, fixed cost, purchasing economies, and one of them is geographic or distribution density, which companies like Meituan and Walmart benefit from. So I’ll go into that, but those are kind of the two ideas for today. More complicated network effects, economies of scale versus based on geographic density. Okay, now when you start to think about truck alliance and the problem they’re trying to solve, it’s actually very, very impressive as an idea. It immediately jumps off the page of this is great. This is a great target for a platform business model because it’s a very, very large opportunity with lots and lots of inefficiencies based on the fact that, look, the system doesn’t work. I mean, platform business models, this would be a marketplace platform, right? I’ve given you five types of platform business models. Number one is marketplace. A marketplace for services where you have two user groups, people who wanna hire shippers, people who ship stuff. which I’ll give you some examples of who they could be, and then people with trucks. And you contract the truck, it picks up your cargo, and it takes it somewhere else. So at first glance it’s kind of like Uber, but instead of moving people, we’re moving cargo. Okay, that’s kind of the first idea. And then, you know, platform business models, I’ve called them like platform network based business models or platform or ecosystem orchestrators, where their goal is to reach out into a larger ecosystem and enable transactions to happen that weren’t happening otherwise, or they were very, very inefficient. because, for those of you who’ve been listening for a while, because the co-occian coordination costs were too high, things like that. But anyways, don’t worry about that right now. But okay, when you start to look at truck alliance, what jumps out at you is this is a really, really big opportunity. One of the reasons platform business models fail, and groups like BCG have studied like why did they fail? And one of the top four to five reasons is the opportunity they were trying to solve was too small. for platform business models to work, you need a big problem, but it has to be a lot of it. It has to be market size, it has to be country size. Okay, so you look at the industry overview of logistics in China, and the IPO filing for Manbang has a lot there on this, but you can read this anywhere. It’s actually a pretty important topic if you’re gonna look at tech in China is to understand the logistics side of the country. Okay, what does it mean? Well, it means you got a lot of transport. trucks, things like that. You got a bunch of warehouses, you got a supply chain. And people are moving stuff all over the country all the time. What are they moving? Industrial goods, consumer goods, raw materials. I mean it’s the e-commerce piece which I tend to talk about, but it’s also you know the supply chain for the whole industrial base. agriculture, chemicals, things like that. So it does tend to be driven by two of the biggest China phenomenon, which are domestic consumption by consumers and the manufacturing base, which serves China and a large part of the world. Both of those industries rely on logistics and supply chain. So you have these big drivers for the logistics side of China. And depending what numbers you believe, China is already the world’s largest logistics market, 15 trillion renminbi in 2020, according to Truck Alliance. So it’s $2 trillion per year. And then when you start to look at it and you realize, this is a prime candidate for a platform business model. Very low efficiency, very high cost. The number you’ll see floated around a lot is that in the US, the percentage of the GDP that is spent on logistics is about 6 to 7 percent, but in China it’s closer to 15 percent. Very inefficient. Now that’s not totally true. You’ll hear that number, it’s not totally true. China, you can view that as sort of a series of city clusters where Beijing is not one city, Beijing is 25 to 30 cities, all interconnected in one cluster that has about 50 to 60 million people in it. The logistics as a percent of GDP within a cluster is actually much, much lower. So all this infrastructure you always hear about in China, high-speed rail, roads, bridges, all of that stuff, what they’re really doing is they’re building these city clusters and within those clusters, that the logistics costs are much much lower but once you move out of them across the vast sort of continental economy then it’s actually very inefficient so it’s a bit of a mix there okay but why is it generally inefficient well not a lot of standards information is totally not clear. Shippers don’t know how to find truckers. Truckers don’t know how to find their next route. You don’t know the pricing. There’s no standards. There’s a decent amount of cargo damage. Nobody trusts anybody because you give your cargo to someone and you’re kind of at their mercy. If they break something, what are you going to do about it? They may try to renegotiate you while you’re on the road and that stuff happens all the time by the way. So you know companies are sort of struggling, you know, do we do stuff in-house, do we do our own logistics, hire our own trucks, so sort of first-party logistics, or we use a third-party company, you know, it’s problematic. And then overall, let’s say 15 trillion rem and be about 2 billion US dollars, 2 trillion US dollars per year, about 45% of that’s agriculture and industrial. That’s something we don’t see in the United States, we don’t see in a lot of other places. I mean, this is a very industrial country still. Okay. Then you start to take apart logistics. What does that mean? Well, it turns out most of that, 50 plus percent of that is transportation, right? Moving things around and within that, let’s say 80, I’m citing the truck lines numbers here. These are directionally correct, but I’m not standing on these numbers, but they’re about right. 80% of that is road transportation, as opposed to moving thing on ships. trains which are cheaper. But when you start looking at road transportation you’re talking about 80 percent of about 50 percent. So let’s say 40 percent of all the logistics spend is on road transportation and you can start to break that into buckets of full truckload and less than full truckload and then express. So express delivery we kind of know about that FedEx things like that. Full truckload less than full truckload. Those are your three categories. Truck Alliance has been targeting the full truck load, but more and more, the less than full truck load. Now, why is less than full truck load so important? If it’s a full truck load, you organize a trucker. Usually it’s a single person who owns their own truck, individual owner operator. They come to your factory, you fill up the truck, they deliver it to another location for you, the full truck. Simple. Well, simpler. Less than truckloads means you’re suddenly starting to put together and aggregate different types of cargo into one shipment. The operational aspects become a lot more complicated. It’s like going from, Hey, I’m Uber and I’m giving a ride to Jeff from his apartment to the airport. versus, hey, I’m Uber and I’m doing carpooling. Well, now I have to pick up three or four different people, get them all together, and you have to manage all the matching and all the pricing for that, which is a lot more complicated. So less than truckload moves you into a more complicated type of situation. Okay, but generally speaking, very fragmented market. Lots of truckers everywhere, lots of independent shipping companies. Most of them are local players. In the US what you tend to see is you see national shipping companies that have a big footprint. We don’t really see that in most developing economies. It’s a lot of local and regional players. The other thing we tend to see in let’s say China, but you could say this about Southeast Asia, is you see a lot of sort of spot demand. when you’re pricing something out, I wanna ship something, you’re getting the spot rate. You’re getting whatever the market is giving in the next couple of days, as opposed to being able to arrange these things, days, weeks, months in advance, which you see in other markets. So it’s this sort of, you know, it’s basically not nearly as developed, which is, makes sense because, you know, it’s still a developing economy. Full truckload tends to be most, in terms of goods moved. You don’t have to aggregate the shipments. You have sort of a point-to-point scenario. You’re not running a truck between four or five different locations to fill up the load and then drop it off. And then on the drop-up side, you’re also dropping it off at multiple places. more complicated. So less than truckload is more complicated. It’s smaller but it’s also growing faster. Why? Well one of the big reasons is because of e-commerce. Small batches, things like that. A lot more variety, a lot more pooling of cargo, things like that. And the trick with this when you’re doing either of these things as a matching service or as a shipping agent, you’re trying to maximize the utilization versus minimize the time. Some people want shipment today, they just want it there as fast as possible, but you also want to maximize the utilization because it’s cheaper. FedEx is all about minimizing time, other companies are all about maximizing utilization. And then you can think about small ticket versus large ticket. Okay, the other dimension to think about, inner city versus intra city, which I always get those words mixed up. Intra city, generally speaking, under 100 kilometers. Now I’ve talked about this before, this was a while ago, Southwest Airlines, which was direct, direct, point to point short haul flights versus other American Airlines, which does long distance. And you can see the same thing in trucking. You see different models based on short haul versus long haul. Anyways, intercity is generally defined as between two cities, intracity is obviously within one. I don’t find that terribly helpful, like as an idea. I just think about it in terms of numbers. Look, are we talking over 100 kilometers? We talking under 100 kilometers? Are we talking more than 500 kilometers? And when that really starts to change is when you start to go intracity, so something short distance. If you look at something like express delivery, generally the profits and the competitive strength follows from taking the packages long distances, not across town, which pretty much anyone with a scooter can do. But to create a national network that connects all the long distances, that tends to be where the competitive power is, and therefore usually the profits. Okay, so then we start thinking platform. We’re gonna build a platform to connect user groups. Who are the user groups? Okay, shippers. This is a pretty big assortment and this is probably where you start thinking about long tail. That, okay, who’s shipping what? Well, you have companies, big companies, shipping things all over the place. You have small companies and you could have very small companies that are not currently using shipping because it’s too difficult. Second to that, you can have sort of third party logistics companies that might hire or might use a platform like this as kind of agents. You could have truck brokers who are working to connect people. There’s a lot of brokering and agenting going on here and a lot of middlemen today. On the other side, okay, we have truckers. Now most of these in China, and this is not uncommon, are sort of individual owner operators. You know, it’s usually one dude who owns this truck. That’s kind of the same thing. And you know, they can have different types of trucks. They can have these drive-in trucks, which you see, you know, sort of look like big rectangles. You get a flatbed trucks that you put stuff on. You could have, you know, there’s a whole sort of category of this and they come in different sizes, but you got sort of a decent assortment there. All right, now, what are they moving? Well, Kind of tons of stuff. I mean, there’s just tons. I mean, it starts to look a lot like an e-commerce platform. There’s so many categories. Fresh produce, grain. grain products, livestock, agricultural products, metals, construction materials, industrial chemicals and plastics, paper products. I mean, it really starts to look like all those tabs on an Amazon webpage. There’s a lot of categories here that can be moved around. And suddenly that’s a lot more interesting than say Uber. Uber, we have consumers and businesses who wanna get across town. That’s what people use Uber for. All right, so. why do these groups have a hard time interacting? What are the coordination or transaction costs in the market that we are gonna solve with a platform business model such that interactions and transactions that aren’t happening or they’re not happening efficiently are start to kind of take off. And I think this is where Truck Alliance has some pretty compelling arguments. So this is from their stuff. Okay, what are the problems for shippers? Now, the way things work a lot in China now is they have logistics parks. You know, these physical locations where people go to find someone and to drop off their stuff and to, you know, hook up with a trucker. And the truckers show up and the shippers show up and then there’s lots of agents and brokers and middlemen and they kind of list on whiteboards and whatever, like here’s what’s available, here’s we got a trucker coming in, we got an order coming in, and they all sort of try to find each other. And it’s inefficient in lots of ways and I’ll sort of go through why, but let’s say you’re a shipper. How do you find a trucker? You’ve got some cargo, you want to ship it, what do you do? You pick up the phone. You start going to a logistics park, you’re basically offline for the most part and it can take days. I mean it’s really not difficult and when you do try and find information it might not be good. The trucker may have been available but now not anymore. You’re probably dealing with brokers for the most part if you’re doing this at any scale. That’s a problem. Okay, you have high costs and the pricing is opaque. you know, all these brokers and agents, they have sort of rental costs for the logistics park. So they have some sort of fixed costs that they’re passing on. There’s a lot of middlemen trying to sort of justify their existence. It’s definitely not efficient. And then you kind of have low service quality anyways. Okay. So you do a deal with the trucker, you hand them your cargo. What do you hope for the best? What if there’s a problem? Do I have insurance? Can I track them? Can I see if there’s a problem? If there’s damage, how do I know? Because cargo gets damaged all the time. What am I going to have to sue them? So there’s sort of low service quality, there’s a lot of faith, and there’s not a lot of trust on either side. Alright, so then you talk to the truckers. What’s your problem? Well, they’ve got just as many problems. They’ve got these trucks which they pay for that have very low utilization generally speaking. Maybe they get pretty good utilization on the trip out. So you contract and you go from your hometown, who knows how far, out hours, maybe a couple days to drop something off. But then how do you pick up an order to come back? So the backhaul tends to have very low utilization. And what do you do? You drive home empty? No, you go to a local logistics park. Well, where is that? Well, then you have to take a separate trip out to the logistics park, which costs you money, time, fuel. That’s a problem. You may have to stay there for a while because the average lead time, they’re saying, is two to three days because this thing is not efficient. So that’s a problem. You’ve got low income visibility. You might make an order today, you might not make an order today. How do you know? Not a lot of ability to do planning financially, also not a lot of ability to do route planning. You can’t plan five routes in advance. I’m gonna go from here to here, pick up an order, go from there to there, pick up an order. And you kind of get limited cash flow, especially if you’re waiting to get paid. You know, if you don’t get paid, how do you fill up for the next trip? And then generally you sort of have not much protection for your interests. What are you going to sue someone? You going to sue these companies? More than likely they’re just going to delay payment. Hey, give me a discount and I’ll pay you today. Or I’ll talk to you next week my friend. You know that stuff goes on all the time. So you can just see like this is a really messed up marketplace and you know it’s just screaming, one it’s very very big, and it’s just screaming for a digital solution that we’ve seen in lots of other places. I mean this isn’t rocket science, we know how this works 15 years in, well let’s say 12 years in for mobility. So that’s all very compelling and into this jumps Truck Alliance. and they start solving people’s problems. It’s a Guizhou based company which is really interesting. Most of the tech companies tend to be in, you know, Shenzhen and Beijing, this one’s out in Guizhou, which is really interesting. But they start trying to solve this problem. So what do they give? You know, they start with some basic listing services. You know. literally the same way Alibaba.com got founded. We’ll just put up a listing service, people can post their orders and then other people can come in, like a big bulletin board. So that’s kind of where it began, but it began on QQ and WeChat and shippers could start to post orders. Here’s what we’re looking for. That went on for quite some time. They merged up, there’s a bunch of history here I’m not gonna go through in terms of M&A and stuff like that, but they basically merged up and became number one. and you know that was their their thing an online bulletin board and 2018 they began to try and monetize that basically offering membership services. So freemium model, basically. Look, anyone can post, any of the shippers can post, the truckers can find them, contact them, fine, fine, fine. If you wanna post more frequently or you wanna post more orders, well then you have to pay us a membership fee. So typical freemium, you give it away to free to most people, a small percentage, you start to charge them. That is a great way to build activity. It’s a great way to build a platform business model as some sort of freemium thing. Over time, they start to move from there into brokerage services, which is actually a little bit complicated. It turns out the taxes are really an important part of this. I’m probably not gonna go through that because it took me like a while to figure out how the taxes play out. But basically… The company comes in as an agent, truck alliance. You know, they take the money from the shipper. We take your order, we take the money. Then we go find a truck to give it to, then we pay them. The revenue in minus the revenue out would be considered our platform service fee. That’s what shows up as net revenue if you wanna look at their financials. Now that would be kind of the basic story. Find they’re taking basically a commission. The tax bit is funny because the value added tax are so significant and they have to, as the the agent, they have to pay those. Their value added tax is larger than their platform service fee, their net revenue. So they actually have to get discounts from local governments that rebate some of the STEM. Otherwise they honestly would probably be gross profit negative. There’s some interesting tax and stuff in there. But now on top of this they also start to add value added services and this is kind of depending on how you want to view it. You could view this as a way to make some money, but it’s not that big. You could view it as a way to build in switching costs, which is kind of what DD has been doing on the driver’s side, which I’ve talked about quite a bit. I think this is, and they actually kind of say this in their filing that value added services create stickiness was the word they use. I think it’s more about getting people on board. businesses comfortable doing this. I think it’s about usage. So what do they offer them? Well if you’re a shipper they offer you a transport management system, you can track your packages, they offer insurance for the cargo and for other things, they offer credit solutions for both truckers and shippers. I mean they actually did quite a bit of leasing here as well. where they’re sort of helping people get around this. They even help people with like electronic toll collection services. So there’s a bit within what we call value add services that I think is mostly about getting people on board and encouraging usage. And they are still really in the early days of monetization. I mean, they’re mostly about getting usage on this platform and getting their network effect going, which is kind of why I called this the struggle to build a advanced or complicated network effect. I think that’s really where they are. Now, if you actually look at their numbers, and I’ll put a couple slides in the show notes about this. The numbers, I don’t know, I mean they’re big, but all the usage numbers out of China are always big. Here’s the ones they’re promoting. 173 billion RMB in platform GTV. So, you know, 25-30 billion US dollars of transaction value happening. 71 million orders fulfilled. They say they cover 300 plus cities. They say they’re covering 100,000 routes, more than 100,000 routes. They say 20% of China’s heavy duty and medium duty truckers have used the service at some point. 2.8 million trucking fulfilled shipping orders and 1 million active shippers. Okay, the numbers I took away from this were okay, 2.8 to 3 million truckers appear to be active on a monthly-ish basis. 1 to 1.3 million shippers, so let’s say you know 1 to 2 million shippers dealing with 3 plus million truckers covering lots of cities. Okay, I mean that’s not small. And that’s interesting. And if the usage grows, certainly there is a large runway for increased utilization, increased activity on this platform if you can solve all these many problems. And I’ll put another slide in the show notes about usage. This was the one that actually got my attention. They have a section called Key Operating Metrics and they basically show average shipper, MAUs, fulfilled orders and GTV on a quarter by quarter basis from March 2019. And basically all of those numbers I just mentioned, average shipper, MAU, fulfilled orders, GTV are basically going up quarter by quarter since March 2019. So that’s relatively interesting. I’ll put that in the show notes. That brings us to the financials, which I have avoided talking about thus far. And they’re not good. I mean, they’re, well, I mean, the company’s very forthright. Look, they call it the early days of monetization. Okay, fine. 2020 revenue and this is net revenue. So this is money in from the shippers you pay the truckers then the money that comes to the company which they call the platform the platform service fee we can call it the take rate 2.6 billion rem And that’s about the same from 2019. It didn’t move. You could call that COVID related or whatever. Now, is that big? No, not, I mean, well, it’s obviously a lot of money, but no, I mean, relative to all those market size numbers I just gave you of, this is a two to $3 trillion logistics opportunity, even at a take rate, that gets you to 100, $200 billion. as a platform play within that massive space and against that it’s at 400 million. So, you know, either this is just slow and steady growth, which is often the case for B2B. I heard it once said, which I thought was totally true, that success in B2C and digital is like catching lightning in a bottle, tick tock, right? B2B is more like mining. It’s slower, but you also know where the gold is, generally speaking. The consumer side’s faster, but it’s hard to predict what’s gonna work and what isn’t. So you could call this maybe slow mining. Okay, so the revenue is what it is. Total operating expenses, basically they dwarf the revenue. I mean, this is, let’s say 2019, which is pre-COVID. So 2.5 billion renminbi in net revenue. Ultimate operating profit negative one billion. And you can kind of guess where all that money’s going. It’s actually, I mean, it’s, cost of revenue is actually their big one. It’s not necessarily sales and marketing, which is often the case when you see numbers like this. It has a lot to do with their value added tax that they’re dealing with, with the cities. And then their, their, their GNA expense seems to be going up. significantly which is kind of strange like 1.2 billion in 2019, 3.9 billion in 2020. That’s a little bit funky. Anyways, early days of monetization. I don’t think there’s a whole lot you can see within these numbers either way but I thought I would sort of point that out. And last topic and then we’re going to switch to sort of the concept stuff. You know, what are their risks? I always like, for those of you who listen to me a lot, you know I like the risk section most. That’s my favorite part of any filing is always the risk because that’s where they have to be honest technically by law, although they don’t always do that. Big surprise, they have to get critical mass on their platform. with truckers and shippers in a cost-effective manner. That’s a good phrase to keep in mind when people talk about we’ve got to get to a critical mass to get our network effect going. They don’t always put that second phrase of in a cost-effective manner. You can spend a lot of money and buy traffic, but if it costs you too much, it’s not gonna work. Their second one actually is one you don’t see very often in platform business models They said one of their big risks was market acceptance That to me is this idea of like look it’s a big big opportunity. I got it Your traffic seems to be good, but nothing like the opportunity and the revenue is small I mean, do you really have product market fit here? Is this thing just taking off? They have 4,000 staff. 50% of those staff are doing sales and marketing. Okay, this could be the early days of priming the pump, getting the network effect going. It’s not clear to me that they have real market acceptance here yet. And I don’t usually say that about platform business models, usually it’s something else. Their monetization strategies may not be successful at their early stage. And then regulatory issues are, this is a highly regulated area of China. The good news is the government’s totally on your side because they all want the logistics to be more efficient. Okay, that’s the scenario. Let me switch over to concept thinking. So if we start to take this company apart in terms of various frameworks, fine, it’s a platform business model. What type is it? It’s a marketplace for services. Great, we know what those are. This is pretty understandable. It’s in a large economy. That’s awesome. It’s not cross border. It’s all domestic. That makes things a little simpler, although cross border can actually be very, very attractive as a play. All right, and you’ve got two user groups. Who are they? Truckers and shippers. the same. That’s kind of a lot like Uber drivers, but the shippers, there’s actually a decent amount of variability. There’s big companies, small companies, e-commerce companies, manufacturing companies. There’s a potential for a long tail or a much sort of increasing variety of types of shippers there. Fine. Those are you two user groups. You’re trying to enable interactions between them. you have to solve, you have to provide certain capabilities to enable interactions. For Alibaba, they had to provide some mechanism of payment, which they created Alipay, and they also had to overcome the trust problem because nobody trusted each other. So they did Alipay and they used escrow payments for a long time. You didn’t release the money until you received the good and checked it was okay. They did dispute resolution, they did warehouses, they did things like that. So what are the capabilities you need to enable these transactions? That’s pretty much what they’ve put under their value-added services. Dispute resolution, pricing mechanisms, insurance. Some degree of credit support for both sides so they can kind of get this I mean those are kind of the big ones but they obviously have you know a transparency issue a trust issue a matching issue And so okay you put the platform together and you realize that you are in the matching and pricing business that’s really what you do you do matching and you do pricing and That’s actually not that easy Yes, you need algorithms, you also need data. You gotta put all the trucks and all the shippers in in the same formats and start to get data and then you can start to do the matching. But in this market, more so than others, that pricing is a problem. If you ever notice that like if you go on a C-Tripper and Expedia, which would be a marketplace for services and you book a hotel. You can choose between lots of different types of hotels and they all have different prices and it’s a very differentiated supply. But you go on Uber, it’s a commodity service, you just want to get from point A to point B and they don’t even give you the choice of which driver and they don’t give you a price that you can choose from. They just tell you, here’s the price. Both marketplace platforms for services, different models based on matching and pricing of commodity versus sort of differentiated services based on categories, things like that. Okay, well, we start to look at trucks and we’ve realized, oh, okay, there’s actually a lot of factors here in terms of matching and pricing. Cargo types, shipping grain, shipping chemicals, shipping bulky furniture, shipping small batches. aggregating demand in less than truckload situations versus full truckload situation. There’s a lot of different cargo types going on here that we’re going to have to think about and they’re going to have different sort of pricing and matching in each of those. Then we start to think about weight. Well, weight matters a lot. That drives a lot of the cost structure. So we’re going to have to have that as a big factor in pricing and to some degree truck selection, big trucks, small truck, things like that. distances, how far are you taking this? Right, across town, across two towns, across the state. That’s a kind of a big thing. I mean, there’s four or five dimensions here, even within a basic approach to marketplace for services, that you realize this is a lot more complicated. And do we just offer prices and then the shippers choose the one they want based on? what the truckers have put up or do we assign a price? And one of the things Truck Alliance does is they have sort of a click and go function where when you post an order, they will suggest a price to you and the shipper can then just click okay. Now you can see how that might be nice from the shipper side but you can see how the truckers might not like that. And that’s the trick with platform business models is you have to make both sides happy. So I think they’re kind of on the edge with that one, which is interesting. My hotels don’t let you do that. Like if you post your hotel’s C-trip doesn’t just say up, here’s how much you should pay for a four-star hotel in that city and then give you those options, right? They sort of let you make the decision. So if you go back to my previous post on three types of network effects. And I sent this out for the subscribers, a very sort of in-depth version. There’s a shorter version I did as a podcast, but three types of network effects. I’ll put the link in the show notes. I kind of laid out, look, three types, fine, direct network effect, indirect network effect, standardization and sort of interoperability network effect. This is an indirect network effect, no big deal. Two-sided, indirect, more, in theory, the more truckers is better for shippers, the more shippers is better for truckers. Fine, that’s easy. But then you start to go through some of the questions I put down there about, you know, what about local versus regional versus international network effects? Uber is mostly a local phenomenon. It’s one of the reasons it’s not a terribly strong network effect. Airbnb is a global thing. The more hotels you have all around the world, the better it is for every consumer in China or the US. you know, the operational aspect is global, the matching is global, so the network effect is global. That tends to be quite powerful. A local one like a commodity service getting from here to the airport in your city, well, the drivers outside of your city don’t help you. And for the drivers outside of the city, you being a consumer doesn’t help them. It’s local, tends to be weaker. Okay, well, you look at truck alliance and you realize, okay, a lot of this is probably local. If they’re talking about under 100 kilometers, that might be much more local. But if they’re talking about a national network, that’s different. I asked about fast and slow network effects. Sometimes these things take off very quickly. I need it today. Let’s go. But then the relationship is over. I’ve never met an Uber driver again. I’ve seen them once. I have no idea who they are. But if you’re on a social network or a Twitter or something like that, you might have a relationship with those people for a long, long time, years. So yes, it’s the same network effect, but the duration of the interaction and the value is much higher. You might follow people on YouTube for years, but you’re probably never going to see an Uber driver again. The degree versus the value of the connections. Certain connections are worth more than others. One of the reasons WhatsApp took off so powerfully was it enabled interactions for communications. but not with anybody, with your family and friends. And those are the ones that matter the most and that you value the most. And they pulled those right from the contact list in your smartphone, which was super smart. So not all connections have equal value. You need to think about that. And you need to think about minimum viable scale versus asymptotic scale. I gotta really learn how to say that word right. Asymptotic, asymptotic scale. you need a certain critical mass on both sides before the thing will work. Okay. VCs call that critical mass, people in economics call that minimum viable scale. Fine, how low is that or how high is that? If it’s very, very low, it’s easy for other companies to do what you do, which is like pretty much anyone can start an Uber in their own neighborhood, it’s easy. But if the threshold is very, very high like Airbnb, to get into that business, you need an incredible number of places around the world to even get in that game. The higher the threshold for minimum viable scale, the more powerful the network effect. Same time, at a certain point, the network effect will flatline. And adding more and more drivers on Uber in my town doesn’t help me, because I can already get a ride. So we can call that aspenototic scale. How high is that? How low is that? One of the problems Uber has is it’s low for both of those thresholds. Airbnb is very high for both of those thresholds. Okay, so what is it for torque alliance? I think the minimum viable scale could be pretty significant. I think if they push towards a national network, then it becomes very high and very hard to replicate. If they’re just giving moving goods around town or between three cities that are all 20 minutes from each other, I think it’s much lower. And I think this sort of asymptotic scale is also quite high. because they’re not necessarily doing commodities. They’re doing differentiated services. The more different types of truckers they add, the more value there is. Now I can send refrigerators, I can send coal, I can sell grain, I can ship chemicals. There’s a level of differentiation such that every marginal user or activity adds increasing value and utility to the other side, which doesn’t happen with commodity services. Anyways, those are my questions from, I don’t know, a couple of weeks ago. And I think those are fine questions for things like C-Trip, Airbnb, food delivery. Most of the stuff I’ve been talking about, I think those are all getting back to my first point. The first platform business models for services went after the simplest easiest stuff to do, the low-hanging fruit. But the point of this talk and the takeaway from this talk is, I think we’re seeing more advanced network effects happening with a company like Truck Alliance, and I think that’s what they’re struggling to solve. Because let’s say we start to look at Truck Alliance. The first thing that jumps out is what I mentioned before, which is less than truckload versus full truckload. Now they’ve said we’re going for less than truckload. That’s a big focus of where they’re going. Okay. That means that you have to start aggregating demand. It’s not like I just call an Uber driver, comes to my house, takes me to the airport. That’s simple. That’s full truckload of Jeff in that car. Now this is like carpooling. The car’s gonna come to me, then it’s gonna go to four other people, hopefully near me, pick them up, then we’re all gonna get dropped off at the airport, or maybe at three locations along the way. That’s a much more complicated exercise in matching and pricing for the first part. but also what is the network effect there? Is it just more drivers and just more riders and the value goes up linearly for a while than at flatlines? Or does adding more drivers add significant values such that it’s cheaper? Does adding more riders make it cheaper for everyone? That’s another source of increased value and utility based on more users of the service. Am I starting to add a direct network effect in addition to an indirect network effect? And carpooling in ride sharing, which is what DD and a couple other companies are jumping into, I think is a similar example to that. So that’s sort of one level of complexity that we’re adding to the network effect. The one that really jumps out at you, well let me get to a simpler one first, then I’ll go to the big one. One of the things about Uber that let’s say Lazada doesn’t have to worry about or C-Trip doesn’t have to worry about is timing, spot demand versus schedule activity. If you want to ride on Uber, you want them right now. So the matching has to happen in real time. But if I want to book a hotel somewhere, I don’t have to match it immediately. There’s a time lag. I don’t need immediate availability. So that sort of on-demand, asynchronous versus synchronous matching and delivering of service is more complicated. And it happens with Uber. It almost happens a little less with full truck alliance because you probably have a day or so. It doesn’t have to be within five minutes or people get annoyed. But yeah, again, what this company is trying to solve is this problem with truckers halfway through a journey, trying to find their next leg or to get themselves home without an empty truck. So they want another load to be scheduled and picked up very quickly. Maybe not within minutes, but let’s say within a day. So they have that sort of synchronous matching problem as well. which is interesting. Fluctuations in demand is another level of complexity here. A lot of the businesses this company is in are cyclical. Industrial, agriculture. So we’re gonna have to keep increasing the supply and the demand on both sides of the platform as these cycles go up and down. Are the truckers gonna move back and forth between different industries as they cycle differently? That cyclicality is interesting when you have to ramp up both the supply and the demand together during certain periods, but then another period you need to ramp it down because the truckers are going to get frustrated because they can’t get any more cargo loads. So that’s kind of an interesting complexity. Okay, so there’s three things that I think would be under the category of advanced network questions. Less than full load, carpooling, that sort of aggregating of demand and delivery. On-demand synchronous versus asynchronous and fluctuations, cyclicality. I’ll put these five things I’m gonna say in the show notes so you don’t have to write it down. Not that I assumed everyone was writing it down. Okay then we get to the big one. The big one is the network effects for full truck alliance are route specific. They don’t, you know, if I’m a shipper, I don’t want a trucker to just take me anywhere within my town. I mean, Uber’s kind of, it’s not really, it’s location specific, but it’s not necessarily route specific. Pretty much anyone in town can take you anywhere. But this is one where like, I need a trucker who’s willing to drive five hours to the west. I need someone who’s going from Kunming to Chengdu. So I need to get demand and supply matched, and I need a critical mass of demand and supply such that I get a network effect on that specific route. That makes it really interesting. You really have to think about the supply and the demand, the two user groups, not just in a city, which is what Uber does. We need a bunch of drivers in Bangkok, we need a bunch of riders in Bangkok. No, it’s route specific. And that’s kind of, I think, the most interesting thing that goes on there. And that leads to number five, which is serial routes, sequential routes. I don’t need to just match, I’m gonna send a rider from Kunming or a shipment from Kunming to Chengdu, but then when that truck gets to Chengdu, I need them to be able to pick up another route, another cargo and go somewhere else. So this idea of network effects based on specific routes, it’s also sequential. You may end up wanting to move your truckers five sequences and you want to see four moves ahead so that you can maximize demand and supply at every stage of that. Uber doesn’t really have to do that. They just kind of like you take someone from one part of town to another, then you say goodbye, thank you. The Uber driver looks at their heat map and then Uber suggests to them where they should go in the next 15 minutes to hopefully find another ride. But they’re not planning these Uber drivers five or six right, you know, five or six trips in advance. And the algorithm is doing all of that across a whole country. So that’s really kind of, it’s fascinating to think about the matching, the pricing and how you get critical mass and how you get a network effect going in this situation. So that’s why I’m calling it sort of advanced network effects. And then I think is the theory for today. I’ve really been thinking about this a lot and trying to sort of map it out on paper and see if I can take it apart. It’s kind of fascinating. And when you look at what truck Alliance is doing in tech, like what do they say their big tech initiatives are? got 4,000 employees, half of them are in sales and marketing, about 950 are in R&D. Okay, fine. They’re building one, two, three, four, five, five to six major tech initiatives. Number one, freight matching, right? By truck type, by cargo type, but also by route. That’s really interesting. Number two, freight pricing. The tap and go recommends the pricing for shippers. I mean, you can see those are really complicated for this company. Number three, tech initiative navigation. you know, tracking the trucks, suggesting routes to them, helping them find repair shops, gas, whatever they might need. Number four, risk management system. That’s mostly, they’re talking about the credit risk because they do some lending and things like that. Insurance models, because they’re offering insurance. And then the big one, which, well, not the big one, the big one on the horizon is autonomous truck driving. You know, this gets us kind of to the Dee Dee scenario where they’re building their platform, they’re doing shared mobility, but then you’ve got autonomous vehicles on the horizon. And doesn’t that wipe out the platform business model? I mean, if it’s autonomous driving, you’re a traditional pipeline service business. You’re not a platform anymore. Now, Deedee says they’re going to go hybrid. They’ll have certain drive rides that they use with their platform of drivers and riders and other they’ll do with a service based on autonomous driving, which is probably going to be the case. I buy that. You know, but what is Elon Musk doing when he talks about autonomous vehicles? He’s going after trucks. Because if you put a big truck on the highway and it’s just going straight for five hours. AI is very good at that. They’re not very good at downtown. It’s too complicated. But they’re really good at going straight for a long time on a road and then pulling off the off-ramp to a designated location to stop. So, you know, you’ve got all this stuff going on and then you’ve got sort of autonomous truck driving on the horizon of this company and that bit may come faster than we think. That’s one of the ones I’m actually looking at is autonomous trucks. If anything is going to come first and really get commercial deployment, I think it’s going to be long-haul trucking or long-haul sort of passenger buses that just sit on one highway for five hours and that’s all they do and then they turn off and stop. Anyways, okay, last point on Truck Alliance, and then I think that’s good for today. They had a nice little page about what are their success factors, and I thought this was actually pretty compelling. What’s their biggest success factor? They say a nationwide network that is able to better serve both truckers and shippers. I think that’s absolutely the goal line for all of this. It’s not local, it’s not within a city, it’s one big national China network for trucking. Basically like what Uber Freight is trying to do. They would have a large user base if this works and they would offer comprehensive solutions for these types of transactions and they’d have better technology because none of these small, fact-minted companies are investing anything like they are in tech. If that works, what do you hope to see in the financials? A network effect and increasing operating leverage, right? That would to me be the goal line. And if it works, yeah, we’ll see. So anyways, that is it for Truck Alliance. I think it’s really worth keeping an eye on this company. I think it’s an important company. The two concepts for today, network effects, basic ones versus more complicated ones. Oh, and I didn’t really talk about economies of scale by geographic density. All right, forget that one. Just one idea for today. It’s too late in the hour for yet another bit of theory. Anyways, that’ll be it for this company. And that is it for me from Rio de Janeiro. I’m having such a good week here. This is, this is one of my best weeks ever. It’s Sunday today, it’s fantastic. I went down to sort of standard Ipanema, Leblon Beach. Everybody’s out, everybody’s crazy. But I’ve actually rented a space at WeWork here in Rio. There was three of them, they’ve closed. No, there was four of them, but they’ve closed one, so I think there’s three now. I’ve never, I mean I’ve studied WeWork for years, but I’ve never really spent time in one. I’ve done tours, but nothing beyond that. So now I’m there every day and I gotta admit, it’s pretty awesome. Like it’s super comfortable. It’s that intangible thing where you just enjoy being there and it’s not like going to work, like, ah, I can’t wait to get out of here. It’s just a pleasant place to be and work. So that’s kind of my, has been my days as I go down to WeWork, sit, have some coffee, beautiful view, beautiful deck work. About four, then I come back and I walk home along the beach in Ipanema, which is always kind of amazing. Then of course I have to go to the gym because this is Rio and going to the gym is basically the law as far as I can tell. Everybody’s fit, everybody’s in shape. There’s so much social pressure to be in shape it’s almost overwhelming, which is probably a good thing. Then it’s off to the gym and then I walk home around the lagoon, which for those of you who know Rio is also spectacular. Yeah, it’s great. I’m having a ball. for about another month, I think, and then finally back to Bangkok after a couple months, and really after about six weeks of me avoiding the question of do I have to quarantine for 15 days? Because when I left the rule was seven days, and then they had the outbreak and then they bumped it up to 15 and then I was hoping they would sort of dial that back as things quieted down which hasn’t happened. They haven’t quieted down anything there. The numbers keep going up. And then I thought maybe I’d dodge it by doing the Phuket Sandbox, but it’s got so many requirements, I’m pretty sure I don’t make the numbers. So anyways, it looks like I’m going back to Bangkok and then sitting in a hotel room for 15 days. I’ve been wondering if people can send you stuff. I would love it if I could get someone to send me my PlayStation. Like, I think they must allow you to do that, right? I could have a friend bring over my PlayStation, I could get really good at some games while I’m there. So that’s my current plan. I’m sending him an email. Yeah, so 15 days in a hotel room, podcasting, writing, and getting really good at. I’ve been doing Red Dead Redemption, Red Demp Redemption 2. That’s my latest one. So anyways, that’s my week. It’s… Yeah, this is one of my better months ever. This was a fluke and it turned out to be one of my best ideas. So go figure. Anyways, that’s it for me. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope you’re staying safe. I hope this is helpful. As always, if you have any suggestions for companies to look at, anything like that, please send me a note. I know some of you do that. I really appreciate it. And that’s it. And I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.