Ok. Let me see if I can impress you today.

In Part 1, I wrote about ANE Logistics, an interesting Chinese company. But I really wanted to make a few points about the nature of logistics and physical networks:

- There is a difference between networks, platform business models and network effects.

- Physical networks are different than digital networks. And franchised physical networks are particularly good at growth.

- Logistics is now digitizing and we are seeing a new type of network emerging. It’s confusing and I’m not sure what this means yet.

Ok. But then it comes to competition in logistics. And this is why people pay a lot of attention to logistics companies. Because we often see “winner-take-most” markets based on these physical networks. And we sometimes see this regionally and even globally.

The key factors in logistics competition are usually:

- Coverage (i.e., you can send to anywhere. So no need to go to any other provider.)

- Speed

- Cost

Reliability and security also matter but those aren’t where you differentiate as strongly. So express delivery markets have consolidated to a few dominant players (FedEx, DHL, etc.). They focus more on speed than cost. But the high volume of express delivery is important in the network effects. Slower freight (like ships) is usually more about cost. Less than truckload (LTL) freight is a mixture of both timing and cost. And ANE Logistics is focused on “express freight”, which is closer to the FedEx model. So why does this happen? Why do many logistics networks consolidate to a handful of winners? What are the competitive advantages that are playing out here? I think there are really three important things that explain this. And this is where I am going to try to impress you. Because I think my framework for competition explains this phenomenon very, very well. The three things that matter are:

- Network effects

- 3 types of economies of scale

- Barriers to entry

The Competitive Advantages of Physical Logistics Networks

First, we go to my 6 Levels of Digital Competition. Any business that is digital or going digital is going to have to compete on all 6 levels. But most of the competitive strength long-term lies in the top 4 levels. That’s Warren Buffett land.

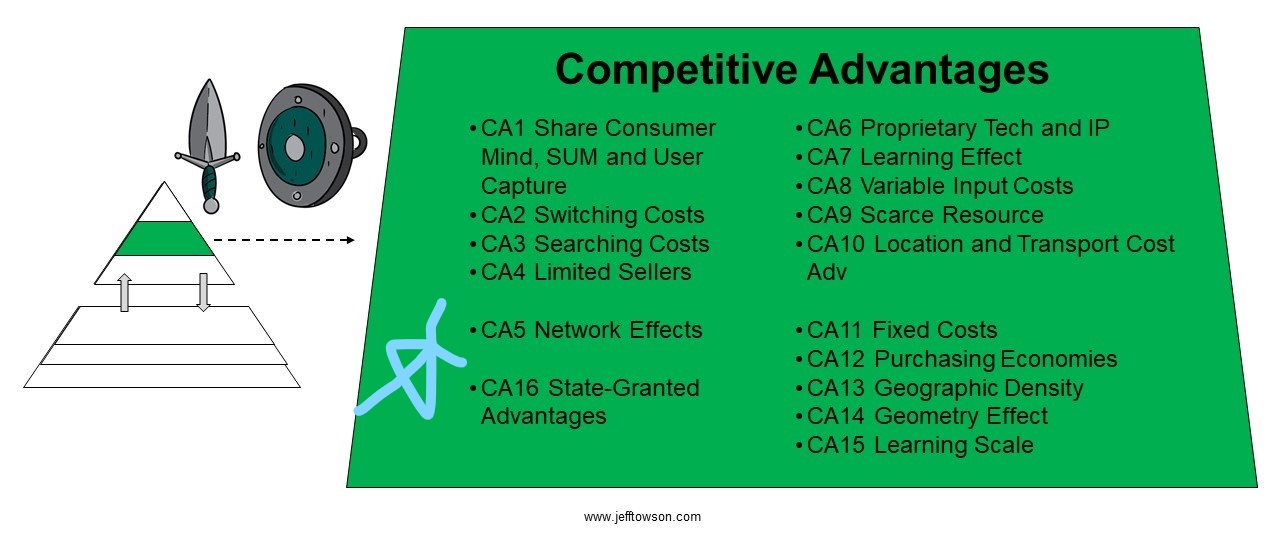

For logistics networks, we are looking at Level 2: Competitive Advantages and Level 3: Barriers to Entry & Soft Advantages. And we are looking on the right of the below chart, which is about platforms and ecosystems (not linear business models).

And when we run the checklists for competitive advantages for ANE Logistics, Network Effects (CA5) is a big one.

Note: This checklist is from Part 3 of my book. Part 1 has been released but Part 3 is due in a few months.

Network Effects in Physical Logistics Networks

Network effects are also referred to as network externalities and demand-side economies of scale. But it’s the same thing. It is a phenomenon where:

The more users and/or usage of a product or service, the better it becomes to specific users. Its value and/or utility to specific users increases with marginal users and/or usage.

The language there is important.

- Think about the number of users and the amount of usage as different.

- There is also a difference between value and utility. Value can be a matter of perception and feeling. Utility is usually functional.

- Value and/or utility increases to specific users differently.

- This is about marginal increases in value and/or utility to specific user groups.

For example, if you join Zoom, then it becomes a more useful service for its existing users. There is now another person they can call. In contrast, if you go to KFC and buy chicken, my chicken dinner doesn’t taste any better.

Think about that for logistics networks. Does more shippers increase the value of the service to others? Does it increase the coverage, increase the speed of delivery or decrease the cost?

Think about what happens when you add one new user to Zoom (a people network). It looks like this.

With one new user (i.e., node), you add 4 more linkages. The value and/or utility goes up with each marginal user.

But with logistics networks, this doesn’t really happen. Not with each individual marginal shipper. What matters is the increase in hubs (i.e., nodes) and truck routes (i.e., linkages).

Most physical networks begin as hub-and-spoke models. We have some hubs, with truck routes between them. But most traffic goes through specific hubs where it is sorted. So we have fewer linkages per node.

But look at the lower left of the diagram, where we add a new route that goes directly between Points A and B. To ship a box from A to B, we used to have to go through C. But when we add a direct truck route, we can go A to B. That is faster (important). And it is also cheaper, because of the fuel and other costs of transportation.

Look at the below right where we have added a new hub. That can create new routes. And it can increase speed and reduce cost. But it also increases coverage.

So this is a network effect, in that significant increases in volume enable more routes and nodes to be opened. And this increases the value of the service to its shippers – lower costs, faster delivery and greater coverage.

One last comment.

Logistics networks are direct network effects. There is really one user group. You could define this as one group with two roles (shipper, receiver) but I think it is like payment and messaging networks. It’s one-sided Note: This means there is no chicken-and-egg phenomenon.

6 Questions For Assessing Network Effects

As I have said many times, there are lots of types of network effects. Some are strong. Some are weak. Some last a long time. Some fade.

Here are my 6 standard questions for assessing network effects.

1. Are these local, national or global network effects?

- The increase in value by usage can happen at different levels. Additional merchants selling on Alibaba in Mexico does not help consumers in China that much. Marketplaces for products tend to be national. Maybe regional in places like SE Asia. Products cross some borders.

- However, marketplaces for services like hotel reservations are usually international. The consumers cross borders. Ctrip and Airbnb benefit from global network effects by virtue of the activity of traveling being significantly cross-border.

- And, finally, Uber offers a marketplace for services that is mostly local. New Uber drivers in New York do not help a consumer looking for a ride in Los Angeles.

- In terms of defensibility, global network effects are the most difficult to replicate. Then national.

- ANE is clearly a national network. And that’s great. Not as a good as DHL and FedEx being global but still really good.

2. What is the number vs. value of the connections?

- The degree of connectedness really matters in networks. How many unique connections each node has is important. It is why network effects in the digital world are more powerful than the radial / hub-and-spoke networks we see in physical networks. Everything connects directly to everything in digital.

- However, it’s not just the number of connections. It’s the value of those connections. Companies like WhatsApp rose quickly by enabling connections of much greater value to users. People used WhatsApp to connect with friends and family and those were more valuable connections. This is why people talk about network clustering all the time. Building social and communications networks off of contact lists on smartphones was a really good idea. It captured the most valuable connections.

- You want to think about the degree of connectedness vs. the value of those connections.

- ANE and physical logistics networks are not that connected. But some locations and routes are more valuable that others.

3. What is the minimum viable scale and asymptotic scale? What is the congestion / saturation / degradation point?

- Economies of scale on the supply side have a minimum viable scale. This is the size you need versus a competitor to have a viable product in the market. It’s the size you have to get to as a new entrant to begin to match the existing player’s offering.

- We see the same phenomenon in network effects (i.e., demand-side economies of scale). There is a minimum scale that makes a product or service viable. This is usually referred to as critical mass by digital strategists. It is important to know what that is for a service. For some, like with Uber, it can be quite low. You don’t need that many drivers in a local neighborhood in order to offer a viable transportation service. In others, like payment and mobile networks, you have to offer national and likely even regional coverage from day one. Nobody wants a credit card that doesn’t work almost everywhere. Nobody wants a smartphone plan that can’t call everyone domestically.

- There is also the asymptotic scale, which is the point when additional users and / or usage no longer add much value. Or when the market is saturated and there is nowhere left to expand to. For example, at a certain point, everyone in the USA had a phone line and adding users in Brazil didn’t add much value to American consumers. It is important to note when a network effect reaches asymptotic scale for each user group.

- If the minimum viable scale and the asymptotic scale are both high, such as in communications and hotel reservations, the network effect is strong and the market tends to collapse to 1-2 players.

- If the minimum viable scale and asymptotic scale are both low, such as in ride-sharing services, the network effect is weak. It is easy to get to minimum viable scale in ride-sharing in a local neighborhood and lots of companies can enter. Plus, the returns to increasing scale diminish very quickly.

- Finally, there is sometimes a point when additional users and usage can cause congestion and/or degrade the user experience. The telephone lines get clogged and you only get busy signals. The cars on a freeway have all stopped in traffic. You have 500 friends on Facebook but you are only seeing updates from 10-20% of them. Note: the Facebook newsfeed has long ago become congested. It is worth knowing at what point congestion, saturation and maybe degradation begin.

- This is where ANE looks fantastic. The minimum viable scale is to offer delivery coverage for every neighborhood in China. That is very high. The asymptotic scale is also really high for the same reason. It’s a big country. And they will likely start doing cross-border at some point.

4. At what scale is the growth linear vs. exponential?

- As mentioned, a network effect can increase at various rates, depending on the platform business model and the specific user group. It can be exponential for a while. It can be linear for a while. It can flatline at the asymptotic scale. It can often be an S-curve overall.

- It is important to map out the shape of this curve for each user group. The increased value and/or utility at different scales is almost always different for each user group.

- For ANE, we are looking at linear growth for shippers for a long time. Shipping volumes will continue to increase. That will increase hubs and routes. And that will increase coverage, decrease costs and increase speed.

5. Are they fast or slow network effects? Are the relationships long vs. short?

- Network effects depend on the frequency, timeframe and length of the interaction and relationship. In the case of communications, there is repeated interactions all throughout the day. There is high frequency, even if they are short calls and texts. And the relationships between people tend to be long-lasting. That is fantastic. Long-term relationships with high frequency interactions.

- Ride-sharing also has frequent interactions but not long-lasting connections or relationships. You may call a driver every day but you do not stay in contact with that person.

- Prominent universities are a great example of slow network effects. Graduates are branded by Harvard and are hired by certain prestigious firms (Goldman Sachs, Google, etc.), usually staffed by alumni. These new graduates rise up over the years and are involved in hiring. They tend to hire graduates like themselves. It is a slow network effect that goes on for decades. But it can be quite powerful.

- Businesses do use ANE over and over for shipping. That’s good. So it’s not particularly fast or slow.

6. What is the directionality of interactions (Facebook vs. Twitter)?

- Facebook is bilateral. Payments are bilateral. Marketplace transactions are bilateral. You need both users to agree. You have to agree to be a friend or to sell your product.

- But YouTube and Twitter are one direction. You can follow various celebrities and colleagues on Twitter, without their approval and awareness.

- Bilateral is usually stronger. But it depends on the case.

- ANE is one directional.

***

Ok. That is a pretty detailed breakdown of the network effects of a physical logistics network. And this is one of ANE’s big competitive advantages. In Part 3, I’ll talk about how ANE has three types of economies of scale.

Cheers, jeff

—–—

Get my new book Moats and Marathons (Part 1): How to Build and Measure Competitive Advantage in Digital Businesses

Related articles:

- ANE Logistics and 3 Types of Economies of Scale in Physical Networks (3 of 3)(Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- An Intro to ANE Logistics and Franchised Physical Networks (1 of 3) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Podcast 26: Is Baidu the New AT&T? The Basics of Physical vs. Virtual Networks.

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Network Effects: 6 Questions

- Physical Networks

- Logistics

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- ANE Logistics

Photo by Zetong Li on Unsplash

Physical network graphic by AI

———-

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.