In Part 1, I argued that there is no new “sharing economy” – which is why businesses like Uber, Didi, Mobike, and micro-rentals for basketballs, batteries and umbrellas were kind of confusing. It was the wrong framework for thinking about them. And that led to a lot of confusion.

What was really happening is something much more interesting: the emergence of new digital disruptors in access businesses. My key points from Part 1 were:

- Forget the term “sharing economy”.

- Instead, think “access business” vs. “ownership business”.

- New digital tools and processes (especially smartphones and mobile payments) can disrupt demand, supply or both.

- Most of what has been happening is digital disruption in access and convenience. Plus really low prices.

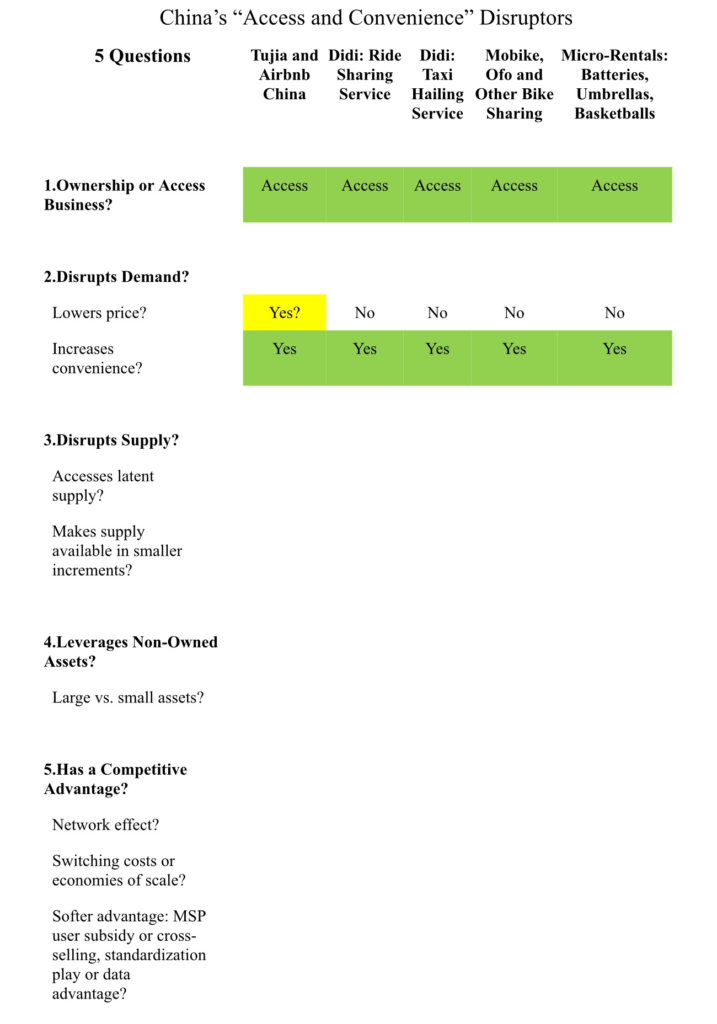

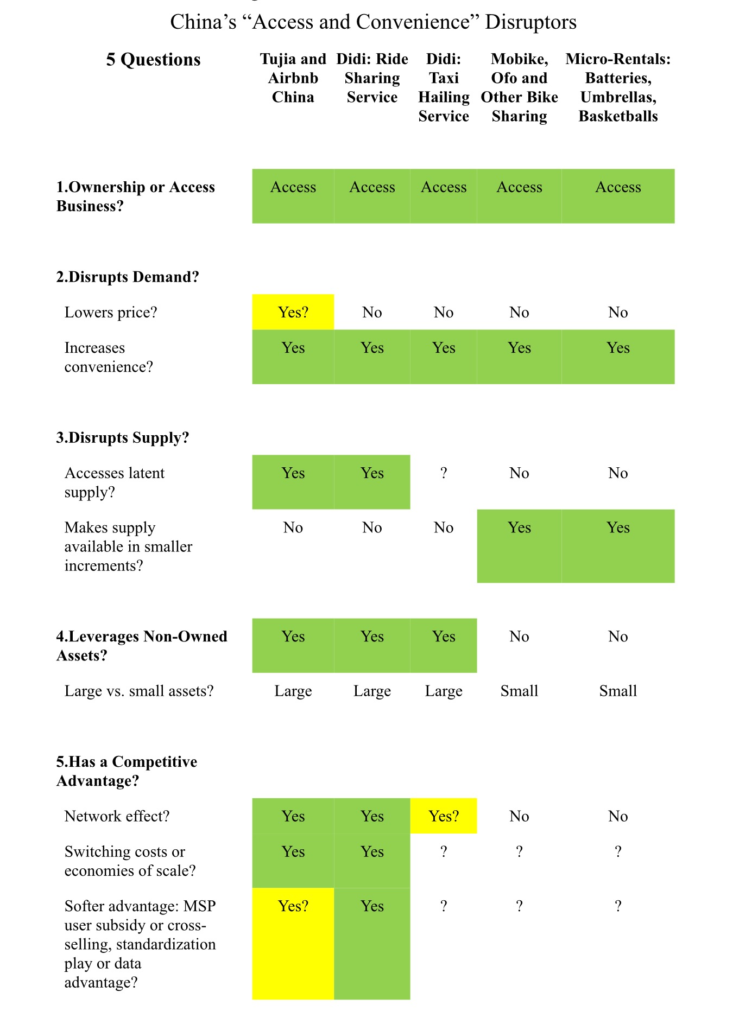

Based on this, here are my five questions for understanding Uber, Didi, Tujia, ofo, Mobike and the new micro-rentals (umbrellas, batteries, etc.). I will discuss each of these businesses in the context of these five questions.

- Question 1: Is this an ownership or an access business?

- Question 2: On the demand side, are new digital tools and processes significantly improving convenience and / or reducing price?

- Question 3: On the supply side, are new digital tools and processes uncovering latent supply and / or making capacity available in smaller increments?

- Question 4: On the supply side, is the business leveraging non-owned assets? Are these large or small assets?

- Question 5: Is there a network effect or other competitive advantage such as switching costs or economies of scale? Is there a softer advantage such as multi-sided platform cross-selling or user subsidies, standardization of technology or other, or a data advantage?

***

Ok. Here is my breakdown of these businesses based on these 5 questions.

Question 1: Is This an Ownership or Access Business?

All those new Chinese companies (Didi, ofo, Mobike, Tujia, etc.) were access businesses. They all offered an alternative to ownership – and they were directly competing against existing access businesses. For example, Didi competes with taxis. Both are access businesses. Mobike was competing with traditional bicycle rental businesses. Tujia and Airbnb China were competing with hotels. And so on.

But these businesses also impact ownership businesses.

- Will fewer people buy apartments because they can now stay in Tujia and Airbnb? Probably not.

- Will Chinese buy fewer cars because of Didi? Possibly. W

- ill Mobike have a major impact on bicycle ownership? Definitely.

Businesses for the short-term rentals of umbrellas, batteries and basketballs don’t even have existing competitors in the access economy. These are only competing with ownership of these products.

What is important is that these new access businesses are changing consumer behavior with regard to some of these products. And they are changing the ownership vs. access make-up of some of industries. I guarantee you Taiwanese Giant Bicycles was very concerned about what was happening with Mobike and ofo.

Per Part 1, if you ask the right question with the right language I find these things become much clearer.

My first question is access vs. ownership because that means very different consumer decision-making and very different business models. These Chinese companies were all new types of access businesses. The next question is if and how they are disrupting their markets.

Question 2: On the Demand Side, Are New Digital Tools and Processes Significantly Improving Convenience and / or Reducing Price?

To paraphrase McKinsey & Co (see Part 1), many of the digital disruptors we see are using new digital tools and processes to give consumers what they really want.

- Software and hardware innovations in cameras have made it so you can see your photos instantly, instead of waiting for film to be developed.

- Steve Jobs made it so you could buy just the one song you wanted on iTunes, instead of the entire CD.

- JD.com made it so you could buy office supplies on your PC without having to go to the store.

- Ctrip made it so you could buy a plane ticket without going to a travel agent or other retail intermediary.

Across the board on the demand side, digital disruptors “make it easy and make it now” (quoting Jay Scanlan, ex-McKinsey). They unbundle. They remove the need to wait. They remove the need to go to a store. They let you buy in smaller increments. These are usually forms of increased convenience.

They can also decrease price, which is discussed below. When looking at disruption on the demand side, increased convenience and / or decreased price is a standard approach.

Convenience is where Mobike and Ofo changed things dramatically. They exposed how inconvenient owning a bicycle has always been. People discovered they really don’t want to store a bike in their apartment. They don’t want to have to lock it up around town when they use it. They don’t want to have to take it home later. They also certainly don’t want to have to go to the rental store, sign a little contract and take the bike for several hours or even a day.

Mobike and Ofo gave consumers what they never knew they always wanted.

They let consumers access a bike anytime and anywhere for as long or short a time as they want. And then they could just leave it when they got off, without worrying about locking it or returning it. Per McKinsey, they “make it easy and make it now”.

This changed consumer expectations fundamentally. And it unlocked a vast existing pool of demand for riding bicycles. Just try selling a traditional bike rental contract in Beijing today.

The main digital tools and processes they were using to do this were smartphones, mobile payment, GPS on bicycles, and smart locks. Their model also required them to blanket cities with bicycles (i.e., make it convenient).

However, in all the China cases cited (see the chart below), these were mostly disruptions resulting in increased convenience, and not decreased price. Taking a Didi or Uber vehicle is not usually cheaper than taking a taxi. In fact, when Didi and Kuaidi first launched they offered taxi hailing, which was a pure convenience offering. Similarly, Tujia and Airbnb were not actually cheaper in China as there are lots of low cost hotels.

However, in other cases decreased price was a big part of disruption on the demand side. Airbnb in San Francisco and Paris is a lot about being cheaper than hotels. These companies will often achieve this cost reduction by removing intermediaries (travel agents, apartment rental businesses, etc.), by increasing supply and by replacing overhead or other labor costs with technology.

This is also why I think the terms “on demand transportation” and “on demand services” are problematic. Mark Meeker of Kleiner Perkins describes Didi and Uber as “on demand” businesses. And while many of the disruptors on the demand side are about making something available “on demand” (transportation, bicycles) and hence more convenient, others are about making things cheaper or with greater selection, which is different. “On demand” is mostly about building synchronous vs. asynchronous marketplaces.

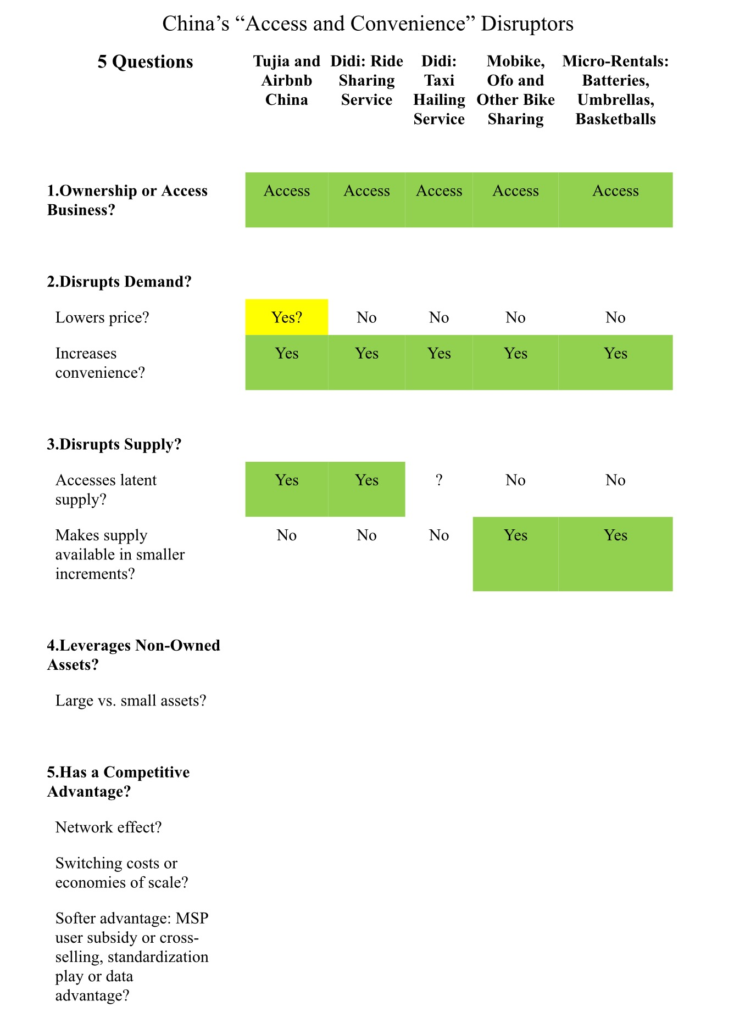

Take a look at the below chart for Questions 1 and 2. I have listed five examples from China and all are definitely access businesses. And they are all about increasing convenience. Tujia and Airbnb are also about lower prices, but I would argue that is mostly outside of Mainland China at this point.

Question 3: On the Supply side, Are New Digital Tools and Processes Uncovering Latent Supply and / or Making Capacity Available in Smaller Increments?

This question uses the language directly from a McKinsey & Co. report, which I think is really good.

On the supply-side, digitization can make accessible supply that was previously impossible or uneconomic to provide. For example, Airbnb brought tons of apartments into the market that were too difficult and expensive to contract individually. Similarly, Amazon Web Services has made huge new storage capacity available to anyone who has any part of their business digitized (i.e., no more need to buy your own servers).

Any time you see an asset that is only partially used, that is probably an opportunity. Such as idle cars, empty bedrooms, half-full servers, and empty parking spaces.

The supply side is where we saw the big difference between Mobike / Ofo and Didi / Uber. And this is why I think they are such different businesses, something that gets lost when they are lumped together under the term “sharing economy”.

Didi seriously disrupted both demand and supply. It is bringing private cars (i.e., underused assets) into the market in ride sharing (not in taxi hailing). And it is disrupting the demand side, as mentioned above, via increased convenience. Plus it is then making a new market between these supply and demand changes. That’s the digital disruption trifecta.

In contrast, Mobike, Ofo and most of the micro-rentals (basketballs, batteries, etc.) were not bringing unused supply into the market. They were buying new bicycles themselves and making them available in smaller increments. They did this by focusing on smaller assets (you could never buy 10,000 cars and put them around Shanghai) and then using GPS, smartphones, smart locks and kiosks. That is why these businesses looked a lot more like vending machines. Most of the disruption was on the demand side. See the below chart.

Question 4: On the Supply side, Is the Business Leveraging Non-Owned Assets? Are These Large or Small Assets?

This is really a sub-point of Question 3.

On the supply side, does the company have to own the assets or can it just leverage them from others? Not having to own the assets is one of the reasons the asset-light economics of Uber, Airbnb and Didi are so powerful.

Mobike and the micro-rental businesses get around this problem to some degree by focusing on small, fairly inexpensive assets. They can actually scale up pretty fast but placing bicycles, maintenance and theft are problems. However, designing your own “smart bikes” means you can do things you cannot do with other peoples’ assets. See the chart above.

This question is going to become really important as businesses start to deploy robotaxis and other autonomous robots. The future of local services is going to look more like Mobike and super smart vending machines than platforms like Uber.

Question 5: Is There a Network Effect or other Competitive Advantage, Such as Switching Costs or Economies of Scale?

Ok. Last one.

And, of course, it is about competitive advantage.

Over the longer-term (not in the early growth phase), competitive advantage (i.e., the ability to limit rivals and new entrants) means you can capture larger-than-normal economic profits. Absent some barrier to protect a profitable business, competitors will inevitably come and whittle away market share and / or profits.

The competitive advantage most software companies and other platform-type businesses are usually going for a network effect. Most of the most ridiculously profitable companies have this (Tencent, Alibaba, Alipay, Airbnb outside of China, Uber, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Match.com, Expedia (in hotels, not airlines) and others). You also see network effects in offline businesses, such as shopping malls (sort of), popular bars, credit cards, and matchmaking services.

Didi has a quasi-monopoly in China because it has a massive competitive advantage, by virtue of a network effect. It has other advantages, but it is the network effect that is the most interesting. At this point, Didi is mostly a two-sided network which means it has to have both drivers and rider populations. Capturing both groups is very hard for a new entrant against an entrenched player like Didi. Plus the larger the captured populations, the superior the service (to a point).

This is what Mobike, ofo and the new micro-rental businesses lacked.

They were not multi-sided platforms and they did not have network effects. They were traditional rental businesses that used digital tools to offer far greater convenience. They were very disruptive to existing businesses (both ownership and access types), but they, as of yet, don’t have a big competitive advantage. This is partly why we saw a flurry of new competitors jumping into bicycle-sharing – but no new competitor for Didi in 2 years. One had a barrier to entry. The others didn’t (yet).

Final Point: Forget the Sharing Economy. This is Innovation in Access Businesses – Mostly by Increased Convenience.

Take a last look at the chart above, especially Questions 1 and 2. All of those new businesses were about digital disruption in the access economy – and most of it was through increased convenience on the demand side. We are seeing a change in how people access cars, bicycles and other assets. These new disruptors are giving consumers what they have always wanted but have never been able to have. It is a purification of demand.

But when we look at supply, assets and competitive advantage (Questions 3, 4, and 5), we can see these are really different types of businesses. The companies on the left of the chart are disrupting both supply and demand and capturing powerful competitive advantages. But much of the press recently has been on the companies on the right, on bike sharing and other “micro-rentals” (umbrellas, batteries, basketballs, etc.). They are not as powerful business models and are mostly innovating in convenience right now.

***

Ok. I hope that was helpful. I think this is going to be how we view a lot of the new AI services emerging. If Mobike was similar to a vending machine business, then robotaxis are similar will be too. And lots of real world services as well.

This is really just the beginning. Thanks for reading, Jeff

Part 1 is located here.

———-

Related articles:

- AutoGPT and Other Tech I Am Super Excited About (Tech Strategy – Podcast 162)

- AutoGPT: The Rise of Digital Agents and Non-Human Platforms & Business Models (Tech Strategy – Podcast 163)

- The Winners and Losers in ChatGPT (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Access vs. Ownership

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Uber

- Didi

- Mobike

- Ofo

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.