The Didi financials are finally out. And they are an interesting mix of good and bad. Didi has market dominance and tech leadership in the largest market for shared mobility. But it is also chronically unprofitable.

For investors, this could be a fantastic opportunity. Because Didi’s ongoing losses will scare off investors and likely lower the share price somewhat. Especially considering the ongoing operating losses at both Uber and Lyft.

Maybe there is a truly great company within the messy financials? And one that could emerge in the next 2-3 years?

Or maybe this is just a muddy situation that will flail along for years.

Either way, I think Didi is a company that the investors who specialize in tech should pay attention to. Your expertise might pay off here.

The Basics of Didi

I talked about this in my podcast on Didi earlier this week.

The main story told in the F-1 is about big usage in a big and growing market. That’s the pitch. And most of that story is, in fact, true. The key numbers for Didi’s usage (from the F-1) are big:

- 493M annual active users.

- 156M monthly active users in the recent 2021 quarter.

- 15M annual active drivers.

- 41M average daily transactions.

And we basically knew this already.

Didi has most of the ride sharing market in China. These numbers are consistent with that. Transportation is usually the second most frequently used local service by consumers online. Food ordering and delivery is usually number one.

The market size and growth numbers Didi put forward are fuzzy and directional. They argue “shared mobility” is going from 2% to 24% of mobility in 20 years. And that “shared mobility” is the future based on multiple growth drivers for demand. Including:

- Urbanization will continue and +70% of Chinese will live in cities in China, like the rest of the world. This is true.

- Regional economic growth will continue. Didi has 3x higher usage in Tier 1 cities versus Tier 4 cities (and below). So that’s another big growth driver. Again, this is true. If I was launching a ride-sharing service in China, I would target 4th tier cities and try to flank Didi.

- Consumption upgrades are a driver. Chinese are upgrading their lifestyles as their incomes keep rising. This should benefit ride-sharing services. As well as Starbucks, Gucci and Apple.

- There is a generational shift in behavior. The argument is that consumers will not buy cars like their parents. I don’t really buy this in China, where there is no long history of car ownership.

Ok. That’s all fine and interesting in terms of market growth. But fuzzy and directional.

I think the problem is defining the market. “Shared mobility” is not a market. I would look at the obvious use cases – such as:

- Daily or frequent transportation within an urban area. Such as commuting and dropping your kids off at school.

- “On demand” transportation within an urban area. Such as getting across town for a meeting. Or going to lunch with colleagues. Or getting home after a night at the bar.

- Special transportation within an urban environment. Such as a trip to the airport or the train station.

And #1 is the really big bucket. Daily commuting. And that use case is served by car ownership and public transportation. Not by Didi. In theory, this could include car pooling services, which Didi is doing. But, except for executives and investment bankers working late, nobody uses Didi to get to work every day.

Didi lives in #2 and #3, which has traditionally been about taxi services and public transportation. So does comparing Didi with the cost of car ownership really make sense?

Didi’s biggest strength is the massive China market. Its biggest problem is super safe, convenient and cheap public transportation. The government is continually building and expanding well-run subways and other forms of public transportation. That dramatically limits Didi’s use cases. The leader in Chinese shared mobility is not really Didi. It is the Chinese government.

The Key Financials

For 2020 (RMB, the Covid year):

- Revenue: 141B. Down from 154B in 2019.

- Cost of Revenue: 125B (88%)

- Gross Profit: 16B (11%)

- Operations and Support: 4B

- Sales and Marketing: 11B (8%). Up from 5% in 2019.

- Research and Development: 6B

- Operating Profit: -13.7B (-10%). Down from -5% in 2019.

For 2019 (RMB):

- Revenue: 154B. 14% y-o-y growth pre-Covid.

- Cost of Revenue: 139B (90%).

- Gross Profit: 15B (10%). Up from 6% in 2019.

- Operations and Support: 4B

- Sales and Marketing: 7.5B (5%). Same % as in 2019.

- Research and Development: 5.3B

- Operating Profit: -8B (-5%). Was Didi closing in on operating break-even pre-Covid?

For 2018 (RMB):

- Revenue: 135B.

- Cost of Revenue: 127B (94%)

- Gross Profit: 8B (6%)

- Operations and Support: 4B

- Sales and Marketing: 7.5B (5%)

- Research and Development: 4.3B

- Operating Profit: -12B (-9%).

If we assume 2019 as baseline operating numbers, then Didi will reach operating break-even and profitability at around 200B RMB in revenue. For example:

- If the 14% growth rate of 2019 had continued (i.e., forget 2020), Didi would have reached operating breakeven in 2021. If the growth rate was 10%, it would have happened in 2022.

- From today’s numbers, Didi will reach operating break-even in early 2023 assuming 15% revenue growth. At 10% growth, it happens in 2024.

However…

You have to take apart the revenue numbers. They are a mix of gross revenue were Didi is the primary service provider (they then subtract out the driver fees and other cost of revenue) and net revenue where Didi is the technology provider and just taking a fee. Ride-hailing in China is recorded as gross revenue. Taxi hailing is net revenue. That is different than how Uber and Lyft record their revenue.

So here’s my question.

Didi has had an effective monopoly in the world’s largest ride-sharing market since 2017. How are they not profitable yet? Note: they acquired Uber China in August 2016.

And how can they get to profitability?

I think there are 4 paths.

Path 1: Keep Grinding Away at the “Mobility Network” (i.e., Didi 1.0)

In my podcast, I described Didi’s current business as Didi 1.0. They call it a “mobility network”, which I don’t agree with. I think it is a marketplace platform for services. Where the services are undifferentiated. They talk about a dual flywheel, which they show in the below graphic.

No, no, no.

I don’t see two flywheels. I see:

- A weak indirect network effect between drivers and riders. It’s a local network effect with a low threshold for viability and a low level of flatlining (from the rider view). It’s an undifferentiated, commodity service so most marginal drivers add little value for riders. It’s biggest strength is its synchronous (the matching has to be done in real time). And there is a large consumer base which adds lots of value for drivers.

- Economies of scale in purchasing for the major operating costs outside of labor. Which are fuel, leasing, and maintenance and repair. Didi has the largest network of leased vehicles in China and +8,000 refueling stations with discounts.

- A persistent supply-demand imbalance based on being the only major player in China.

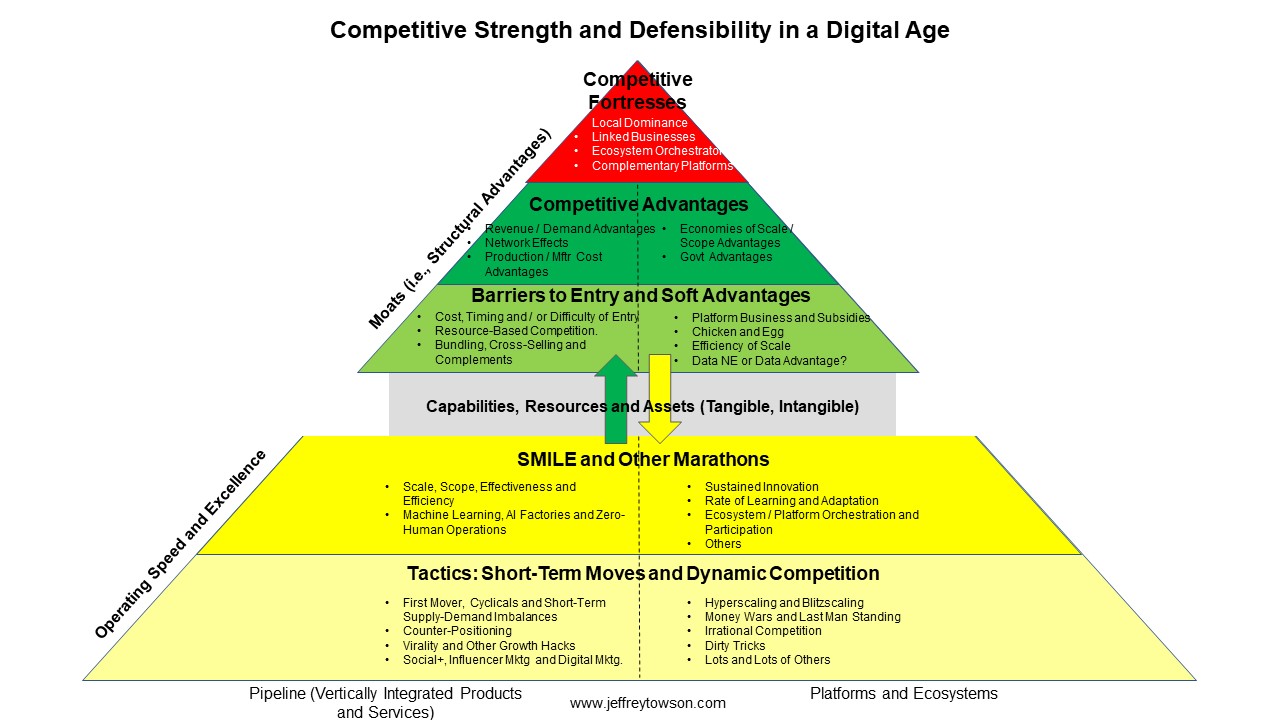

All three of these are in my pyramid at the top, under Competitive Advantages.

Note: Didi also has some driver switching costs and some weak barriers to entry based on chicken-and-egg. And they are running an operational marathon based on Ecosystem Orchestration.

But overall, it’s not a lot of competitive strength and defensibility. Didi lacks most of the major competitive strengths we associate with platform business models. Even at their large scale. And this is further undermined by:

- Large tech competitors that are poised to enter ride-sharing at any moment. Alibaba and Meituan both have a foot in ride-sharing and could easily expand.

- Public transportation as a large and constantly improving and expanding low-cost substitute.

The net result is Didi is in a vulnerable position. They are unable to decrease their labor costs or to raise their prices. And they keep offering consumer discounts and driver incentives, despite being the only major player in the market.

Given this, Path 1 for getting to operating profitability is to stay the course.

- Keep growing the number of users and their usage. Both domestically and increasingly internationally.

- Keep actively defending the core China business with discounts and incentives. Keep the take rate at 10%. Protect market share.

- Build driver services that lock them in and increase Didi’s purchasing economies. This will also lower some major operating costs per kilometer. Keep leasing drivers cars at rates 20% below market. Keep offering them fuel discounts. Help them obtain and operate vehicles at costs below competitors.

- Gradually grow to operating profitability in 2-3 years.

I think this is Didi’s default plan.

But it is not all they are doing.

Path 2: Become Meituan (or ByteDance) Right Now

If Meituan CEO Wang Xing was running Didi, he would have moved into other services years ago. That guy jumps from group buying to mobility to hotels to whatever like it is nothing. He uses demand and activity in one area (like food delivery) to jump into another. Often to low frequency, high profit areas (like hotel reservations). Meituan today (like Gojek in Indonesia) offers a suite of local services to its big user base.

Didi has the same problem Meituan did when it went public. It had lots of usage but was unprofitable. And its core business was just not a cash engine. And you definitely a need cash flow to compete in digital China. All the major players have a cash engine. Even slow growing Baidu has its core search engine. For Didi, getting to operating breakeven in ride-sharing is not enough. They will need a source of cash generation.

Note: ByteDance is also great at this sort of jumping around. They don’t create one new app every year. They create dozens of them every couple months. They are always creating and testing new apps against their current user base. That is how they ended up with TikTok.

I think Didi is too trapped in their identity as a “mobility company”. I think they need to forget that. They should aggressively go after where the biggest proven cash flow is. Even in an unrelated area.

Note: Didi is now offering food delivery in Mexico. You can see DidiFood guys are all over Mexico City on their scooters. And pairing ride-sharing with food delivery is also what Grab and Uber have done. Food delivery is actually better than ride-sharing (it’s a differentiated service with lower costs and stronger network effects). But it’s not an awesome cash engine. And Didi doesn’t need another high frequency, low profit service. Didi needs high margin services. And it’s big user base gives it the ability to target low-frequency services that offer profits. That’s what Meituan did.

Overall, I think Didi needs to get back onto the frontier of digital China. Plan 2 is to start acting like Meituan. Jump into different services. I think Didi should have 15 new pilots running in China right now. And should be doing a lot of M&A.

Path 3: Transition to an Electric Vehicle Mobility Platform (i.e., Didi 2.0)

In the F-1, Didi describes its future as a “world where AI and big data power a shared, electric, smart and autonomous mobility network.”

That is an important phrase. You can see all their key strategy words in that sentence.

- “Shared”

- “Electric”

- “Autonomous”

- “Mobile network”

I thought they detailed their strategy quite well in these 5 paragraphs.

The first two bullet points (shared mobility, auto solutions) is what I described as Didi 1.0. That is about growing their current marketplace platform. And building out on the driver side to increase economies of scale and lower the operating cost structure.

However, the third bullet point (electric mobility) is what I call Didi 2.0. That is taking their current platform business model and putting as many drivers as possible in electric vehicles.

Why?

Because that lowers the operating and fuel costs per kilometer.

Look at what makes up their cost of revenue line (that is 90% of revenue).

- Driver earnings and incentives

- Depreciation and impairment of bikes and e-bikes

- Vehicles

- Insurance costs

- Payment processing fees

- Bandwidth and server costs

And this does not include the other operating costs born by drivers. Such as fuel, maintenance and leasing.

But electric vehicles have lower operating costs, especially fuel. And they are cheaper to maintain. Moving a large portion of their fleet to electric vehicles could result in lower fees to consumers, decreased costs for drivers and increased gross profits for Didi. Depending on how the cost savings are distributed.

Electric vehicles also require building out support services and charging infrastructure nationally. Didi says they have +80,000 charging devices in China now, of which 30,000 are by Didi and 58,000 are by partners. They say this is 30% of the charging market in China. Assuming this is exclusive (i.e., no other ride-sharing companies allowed), that should create a new barrier to entry for potential entrants like Alibaba and Meituan.

Overall, Didi 2.0 is an electric car version of their current marketplace platform looks significantly better than the current version. It lowers the operating costs, it changes the unit economics and it strengthens Didi’s competitive position. In theory anyways.

Note: Didi launched their ride-sharing electric vehicle in November 2020. It looks pretty cool.

I think Didi 2.0 is most of what they are talking about in going “beyond building and maintaining the network”.

Electric vehicles also gives Didi a running start at moving to autonomous vehicles.

Path 4: Transition from Platform to Pipeline with Autonomous Vehicle (i.e., Didi 3.0). Didi Becomes Tesla?

This is the fourth bullet point on their strategy. And this is the game changer. This is the big technological disruption looming in Didi’s future. Once autonomous vehicles start doing robotaxis (note: taxis are Didi’s primary competitor), the cost structure drops dramatically. And it will keep dropping. That’s what hardware and software (and not labor) do. Imagine autonomous robotaxis giving rides 24/7. Constantly patrolling the streets of a city by the hundreds of thousands. They will be much cheaper. They will be safer. And supply will be flexible, with more robotaxis coming off the assembly lines as needed. The system will maximize utilization per car and per fleet.

Ironically, Didi’s future is going to look a lot more like their bike-sharing business than their mobility network.

Recall, Didi’s ride-sharing is a marketplace platform for services. It enables transactions between riders and drivers. But Didi’s bike-sharing business is a traditional pipeline service business based on deploying assets all over town. It’s more like a vending machine business than a digital platform. Autonomous vehicles will be the same. You won’t need the drivers anymore. And Didi won’t have a platform business model for this.

Didi says it is developing Level 4 autonomous driving with its partners. And it aims to be the operating system.

Um. Ok.

In theory, Didi has some advantages in mapping and in data. At least, today. And it certainly has customers and demand today.

But let’s not kid ourselves. This is an entirely new business in its earliest days. Didi has no real advantages over the many other companies going after autonomous vehicles. And while Didi says it is going for a hybrid supply (drivers plus autonomous), this game could end up being mostly autonomous.

How is this going to play out?

Can a software company like Didi end up controlling just the demand, data and operating system? And then the car manufactures are just going to be suppliers? That would be like the Android model. That could be the future in some situations like robotaxis. Or maybe in government partnerships in public transportation?

But companies like Tesla are creating vehicles that are integrated hardware-software solutions that can go anywhere and handle any environment. And they are constantly upgrading their capabilities in ways that only an integrated hardware-software product can. That is more like the Apple model.

We see different competitors for each approach. Xiaomi, Nio Huawei and Tesla are going after the Apple model. Baidu, Google and others are going after the Android model. It’s all confusing. But the one thing we know is this is going to be a long and expensive fight.

- Can Didi compete successfully with these companies in this big, expensive endeavor?

- Is it going to keep partnering with automobile companies?

- Is it going to partner with the government?

I don’t know.

***

For me, I’m looking at Plan 1 and 2 in the next 1-2 years. Those have have the highest likelihood of getting to operating profitability. After that it is Plan 3.

That’s it from me today. I hope this was helpful.

Cheers from Rio de Janeiro – where monkeys are crawling in the window as I write this.

-jeff

–——-

Related articles:

- Why Didi Is Dominant But Still Unprofitable (Asia Tech Strategy – Podcast 87)

- A Day in the Life of a Didi Chuxing Driver (Pt 1 of 3)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Network Effects: Indirect

- Economies of Scale: Purchasing Economies

- 5 Forces: Substitutes

- 5 Forces: Threat of New Entrants

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Didi

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to supercharge digital growth and build digital moats.

I am a partner at TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase growth with improved customer experiences (CX), personalization and other types of customer value. Get in touch here.

I am also author of the Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.