From the beginning of the China bike-sharing phenomenon, I have been struck by how pervasive these companies have become so quickly. Just think of how often you are presented with an image of a Mobike or Ofo bike in China on a daily basis. You see these brightly colored bikes literally thousands of times every single day – on the street, in the park, near the subway, and so on. Every time I walk out of my office or home, I am almost overwhelmed by their presence. I sometimes count how long it takes for me to see another of these bikes. I rarely make it to 10 seconds.

In Part 1, I argued that the startling power of these businesses follows from their deployment of “assets in the wild” in huge numbers. In this part, I dig into how their usage grows so fast.

***

I spoke with Chris Martin, Mobike’s vice president for international expansion, about how bike usage grows in a city versus the number of bikes deployed. And it turns out it is pretty complicated.

- It depends on the city itself. Is it flat or hilly? What is the geographic size? What is the population size? What is the economic level of the population?

- It depends on the degree of local competition in bikes. Is it an open market or are there already significant competitors?

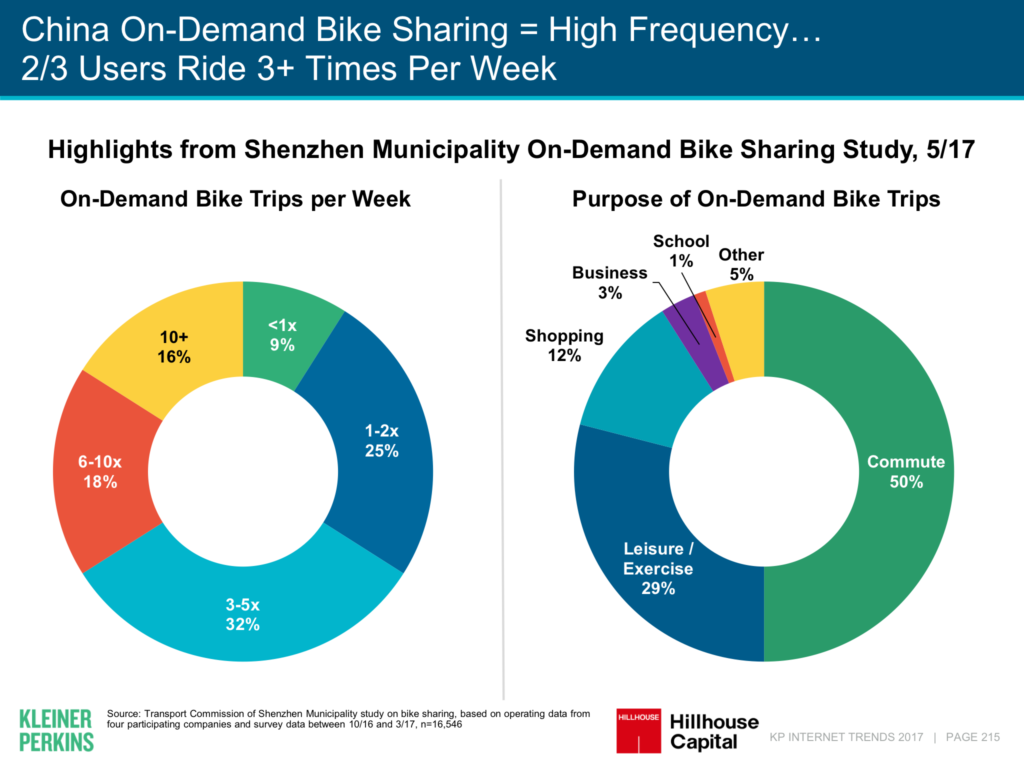

- It depends on the public transportation systems. According to the 2017 Kleiner Perkins / Hillhouse Capital Internet Trends report, 50% of bike rides in China are to the subway or back (see their chart below).

- It depends on mobile payment adoption (very high in China).

- And there are other factors like government support, consumer adoption rates (high in China), and so on.

But one thing is clear. These bikes grow organically and very rapidly in their usage – and this growth requires virtually no marketing spend or support from headquarters. It is an amazing phenomenon that is driven almost entirely by the bikes (i.e., the wild assets) themselves.

It is worth discussing in detail how usage actually grows in a city.

It is worth discussing in detail how usage actually grows in a city.

For bike-sharing, the process typically begins with the deployment of a smaller number of bicycles. For example, when launching in Manchester UK, Mobike started by placing about 1,000 bikes on the streets downtown. And it did so as part of an official launch day when they also had a promotional event. Often Mobike will do these launch events with a local government official or a prominent company head. Having government support ahead of time is critical, especially in international markets. Media outlets also cover the launch event. And Mobike does some social media at launch as well. But basically, a small number of bikes are deployed, word gets out (to some degree) and then Mobike basically just waits.

What happens next is important. The bikes just sit there on the sidewalk and Mobike doesn’t really do much. They wait. And eventually curious people walk up and check out the unusual bikes. When these bikes are in the public spaces, like downtown sidewalks, people do notice them as they walk by. They stand out on a sidewalk in a way a new product on a store shelf does not.

A few daring customers (i.e., the early adopters) see the bikes, stop and download the app on their smartphone. They register and pay the deposit successfully. And then they just scan the QR code on the bike, hop on and ride off.

The important factor in this process is that the bikes themselves attract the users, get them to download the app and then deliver the service to them. The marketing, sales and delivery of the service are all done by the asset on the sidewalk. This goes straight to my definition of a “wild asset” in Part 1. Attribute 2 of my definition was that the asset can market, sell and / or deliver its product or service mostly on its own.

And while a stationary bike in a public space gets noticed, a moving bicycle is much better. Virtually everyone on the street notices the early adopters riding around town on these bikes. So then other people download the app and try unlocking a bicycle themselves. Word of mouth is also important at this stage and people do tend to explain to others how to unlock and use the bikes.

Usage starts to increase, naturally and organically. And early adopters are quickly joined by typical middle class customers. And as usage increases, Mobike deploys more bicycles and the self-selling process repeats itself. The bikes are marketing and selling themselves, so more bikes means more marketing and more sales. And fairly quickly it becomes a mass market service that is used by virtually every demographic within a city.

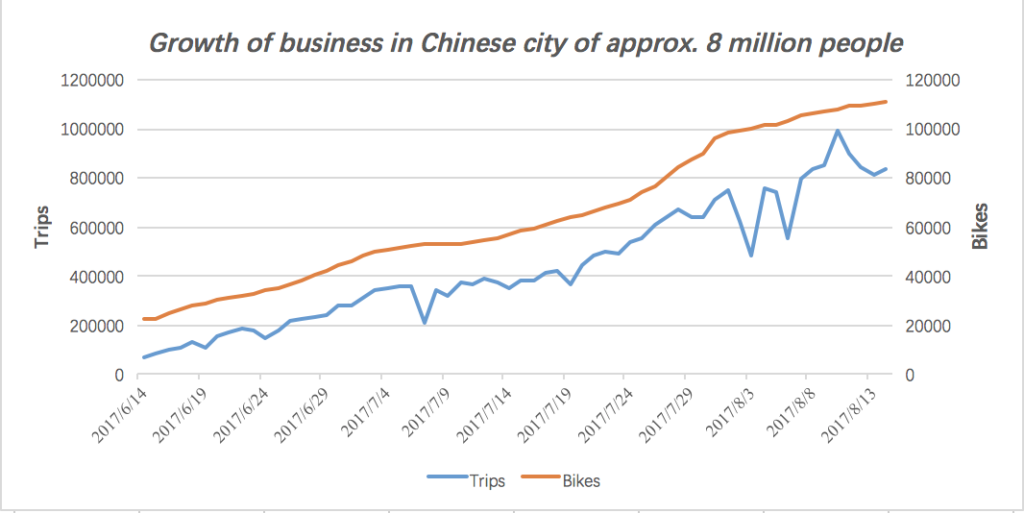

Below is a chart from Mobike for usage vs. # of bikes deployed for a typical Chinese city of 8 million. Note it is fairly linear and not exponential like social media.

And while Mobike supported the process with a launch event on day 1, by day 3 they were really not doing significant marketing or sales spending. The growth curve shown above happens on its own and that is the power of wild assets. Following the launch in Manchester, the company reportedly had 20% day-on-day growth in usage for several weeks. And the more bikes they deployed the more growth in usage there was.

And while Mobike supported the process with a launch event on day 1, by day 3 they were really not doing significant marketing or sales spending. The growth curve shown above happens on its own and that is the power of wild assets. Following the launch in Manchester, the company reportedly had 20% day-on-day growth in usage for several weeks. And the more bikes they deployed the more growth in usage there was.

I asked Chris what he thought the biggest challenge was for growing usage and he replied it was mostly about removing barriers to this process. The usage happened naturally and you just had to remove the barriers to that. So they needed to get government approvals and support. They needed to make registrations and payments as easy as possible. They needed to have the bicycles in the right places. And in China, Mobike actually does less promotion than internationally because mobile payments are so common and people will pretty much try anything with a QR code on it these days.

My Definition for “Assets in the Wild”

In Part 1, I argued that a wild asset has three key attributes:

- The asset can exist mostly on its own in the wild.

- The asset can market, sell and / or deliver its product or service mostly on its own.

- The asset can be released in large numbers.

I think this definition captures much of the above story. Very few products and services have this much impact in a community and grow organically this fast. And even fewer do so for free (after the cost of the bikes).

Better than Wechat and Coca-Cola?

Two companies that come to my mind when thinking about this are Wechat (or Facebook for Westerners) and Coca-Cola. Both also have tremendous sales and marketing power. I find comparisons with these two companies pretty useful.

Facebook and Wechat spread really quickly. And at the time, everyone started talking about the power of social media and “viral marketing”. You sign up for Facebook or Wechat account because your friends forwarded you a request. Or you sign up for a free email account because an email from your colleague has a tag at the bottom asking you to sign up. Viral marketing travels from person to person, usually between friends and colleagues. And it is also very low cost, if not free.

So that is somewhat similar to what is going on with these bikes. But social media and viral marketing tend to be exponential, not linear. And they are largely an online phenomenon while bike-sharing is happening in the real world.

Coca-Cola is arguably the champion in China in terms of real world product marketing and sales. They have overwhelming distribution, sales and marketing reach. You can buy a Coke on literally every block in China – in supermarkets, convenience stores, vending machines, or just little at stalls. And their marketing is also everywhere – on billboards, on signs at stores, on little stalls, and so on. So this is a physical product with a dominant presence, like these “on demand” bicycles.

I think the difference is Coca-Cola is largely within traditional distribution and retail channels, while these bicycles exist in the public spaces. And it also took Coca-Cola +20 years build such a presence in the real world. Bike-sharing happened in about 12 months.

***

“Assets in the wild” have a sales and marketing power similar to these big companies, but it is also clearly something new. They are sort of online like Wechat (you buy the service with your smartphone) but they are also a physical product, like Coca-Cola. But the product exists outside of traditional distribution and retail channels. And the product sells itself without staff or stores, sort of like vending machines.

The more you dig into these questions the more interesting it gets. Deploying huge numbers of mostly independent assets into the wild strikes me as an entirely new sort of thing. And something that is impressively powerful and just beginning.

That’s it for Part 2. In Part 3 and Part 4, I go more into the economics of these assets and what I think is coming next.

Thanks for reading, Jeff

Part 1 is here.

Youon bikes always look to me like an Ofo and Bluegogo had a baby.

——-

I write and speak about “how rising Chinese consumers are disrupting global markets – with a special focus on digital China”.

Top photo by Jeff