Eight years ago, I started going through the Berkshire Hathaway holdings. My goal was to reverse engineer different types of moats. And because most everything Buffett buys has a moat, this was a good place to start. And I ended up going through pretty much everything Buffett had invested in over 40 years.

I later combined this with digital strategy and that got me a lot of my current frameworks.

However, on that first pass, I looked at Verisign Inc (Nasdaq: VRSN) and was stumped. It has been a significant Berkshire holding since 2012-2014. And even today, it is in the top 20 of Berkshire’s holdings by value (worth about $2.6B).

But it was a confusing company. It’s a domain registration business. It’s deep in the digital infrastructure created in the 1990’s. And I didn’t have my digital frameworks finished at that point, so I ended up skipping it.

But this week I finally took another look. And, with the right frameworks, it’s not that complicated. If you view Verisign as a regulated utility, it’s pretty straightforward.

Note: Berkshire has a long history of investing in regulated utilities, although mostly at the local level.

So this article is my breakdown of Verisign, its moat, and the key factors going forward.

An Introduction to Verisign

From the 10K, here’s how Verisign describes its business.

That’s a bit wordy. Here’s how I see it.

Verisign is a domain registry service. Which means it provides online identities for websites – and therefore for individuals and businesses. In particular, Verisign has the contract for .com and .net, which is where most ecommerce happens. And if money is changing hands, then verifying identity is more important.

In the real world, online identity is pretty straight forward. The government gives you a driver’s license or a passport. Or a business license. It’s a piece of paper in your wallet and in a government file.

But for online identity in the digital world there’s no piece of paper. It’s a digital file. It’s done by private businesses (not govt). And it’s a bit grayer. For example:

- LinkedIn provides a widely accepted online identity / resume for professionals.

- Adobe offers document signature functions.

- Facebook is often accepted as form of online identity.

And the digital world has a lot more interactions than the physical world. It’s not checking your ID once a day. It’s millions of ongoing interactions, usually at great distance. Between countries. Between different types of entities (people, webpages, apps, emails, texts, etc.) And for lots of types of interactions (commerce, communication, dating, etc.).

So Verisign was an early mover in providing certification of online identity for webpages. That is still it’s primary activity.

However, Verisign is also sort of functions as a phonebook and switchboard for connecting with a .com or .net webpage. When you type in a particular website, you are dealing with your local ISP or a local registration. You could easily be redirected to another site that is posing as your target website. So, Verisign has a role in verifying that you are at that page and have not been re-routed to something else.

I view Verisign as an online ID card for websites. As a bit of a phonebook and switchboard.

All of this is the result of Verisign’s exclusive arrangement with ICANN for .com and .net. And to some degree, with the US Dept. of Commerce.

This is easier to understand if you know a bit of the history of certificate authorities.

The Strange History of ICANN, Trusted Certificates, and Jon Postel

Verisign was founded in 1995 as a spin-off of the RSA Security certification services business. At the time, Verisign said it provided “trust for the Internet and Electronic Commerce through our Digital Authentication services and products” (from Wikipedia).

It was a certificate authority or certification authority (CA), which is an entity that stores, signs, and issues digital certificates that certify the ownership of the public key for the subject of the certificate. This enables others to rely upon signatures or on assertions made about the private key that corresponds to the certified public key.

Basically, a CA issues digital certificates and acts as a trusted third party verifying the identity of a site. They are trusted both by the subject (owner) of the certificate and by the party relying upon the certificate. And a common use for certificate authorities is to sign certificates used in HTTPS, the browsing protocol for the World Wide Web.

Trusted certificates are an interesting subject. Because creating trust was critical for creating the secure connections between servers on the Internet. Such certificates are essential to stop malicious parties trying to circumvent the route to a target server (referred to as a man-in-the-middle attack). In this case, the client uses the CA certificate to authenticate the CA signature on the server certificate, as part of the authorizations before launching a secure connection.

As I’ve said many times on my podcast, digital business is all about creating value with connections and interactions.

And this depends on lowering the coordination / transaction costs of interactions. That’s really what companies like Facebook and Alibaba do. They lower coordination / transaction costs so two parties can interact in a way they could not before.

And coordination / transaction costs include finding the other party, reducing information asymmetries, completing the transaction and other factors. But a big part of this is reducing the lack of trust with a distant or unknown party. You are naturally hesitant to send money to a merchant around the world unless there is a certain amount of trust. Is this person who they say they are? What is their reputation? Will I get my goods? Certificate authorities that verify online identity are a big part of that trust.

Now Verisign eventually sold its original certificate business to Symantec in 2010. At the time, it had more than 3 million certificates for everything from military to financial services, making it the largest CA in the world. But it is still mostly in the mostly in the same business today. It still mostly provides trusted online identity.

Which brings us to Jonathan Bruce Postel and ICANN.

Jon Postel was one of those unknown guys who played a key role in building the original internet. He was an American computer scientist who was referred to as the “god of the Internet”.

And he had a big role with respect to standards.

- He was the Editor of the Request for Comment (RFC) document series

- He had a key role in Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP).

- And he administered the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) until his death.

This entity (IANA) was the key domain service registry prior to ICANN. And he apparently maintained it as a side project in his office.

In 1998 (upon Jon’s death), IANA was transferred to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). And that is still the organization that oversees most domain names today.

ICANN was launched as an American multi-stakeholder group and nonprofit organization, although it has had an evolving relationship with the US government. So it is sort of an outsourced government entity. The contract regarding the IANA stewardship functions between ICANN and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) of the United States Department of Commerce ended on October 1, 2016, formally transitioning the functions to the global multi-stakeholder community.

Much of ICANN’s work is in the Internet’s global Domain Name System (DNS), including:

- Policy development for internationalization of the DNS

- Introduction of new generic top-level domains (TLDs)

- The operation of root name servers.

Today, ICANN has its offices in the Playa Vista neighborhood of Los Angeles. This is the little business part between Los Angeles Airport and Marina del Rey. And it is in the same building as the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute (ISI), which is where Jon Postel used to work.

Ok. Let’s get to Verisign today.

Note: A lot of this section was from Wikipedia. It’s mostly not my thinking or original. Assume it has quotes around most of it.

Verisign Today Has Great Financials.

Over the past +28 years, Verisign has had a role in .gov, .org and other top level domain name registries. But today, it is overwhelmingly about its role as the exclusive .com and .net operator for ICANN.

This role is by virtue of two contracts with ICANN, which are up for renewal every 6 years. And they make Verisign the wholesaler for .com and .net domain names. It’s customers for these domain names are retail businesses such as GoDaddy and Network Solutions.

However, Verisign is highly regulated by the terms of its ICANN contracts. In particular:

- It is limited to acting as a wholesaler that sells to domain registry services like GoDaddy and Network Solutions. It cannot enter the retail business itself (although it did in the past).

- It is limited in what it can bundle with other products / services.

- Its wholesale price for retailers is set by the contract (about $9 per year per domain name renewal).

- Its whole price increases over the life of the contract are set (between 6-10% per year).

- Its payments to ICANN are also set (about $1 per year to ICANN per domain name renewal).

In addition to the ICANN contracts, Verisign can also have regulation from local governments.

So looking at Verisign today, analysts pay lots of attention paid to its contracts with ICANN. In theory, this creates a lot of uncertainty.

However, in practice, these contracts have been renewed mostly automatically every 6 years. Verisign has the presumptive right of renewal. Which means the contracts are usually not sent out for competing bids.

For example, the .net contract expired in 2023. It was extended to June 30, 2029, with a wholesale price is $9.92. And the new agreement gives Verisign the right to increase prices to $19.31 at the end of the six-year term.

The .com contract will expire in 2024.

So, Verisign is exclusive for .com and .net and acts like a regulated utility / wholesaler. It’s a pretty simple business.

And it has really attractive financials. Because it has no significant cost structures. It’s a pure business that mostly maintains a registry (i.e., a big file). And its operations are mostly servers and security functions. As a business, it’s a really predictable cash machine.

Value investors like Berkshire like the stock because it is easy to predict. You can predict the number and growth of domain name registrations and renewals each year (it is about 173M right now). And you can see the future pricing detailed in the contracts.

So you can fairly accurately predict its cash flow going forward during the life of the contracts. And then you just need to think about the optionality every six years. It’s a predictable business with great cash flow. Although it does not have a big growth story.

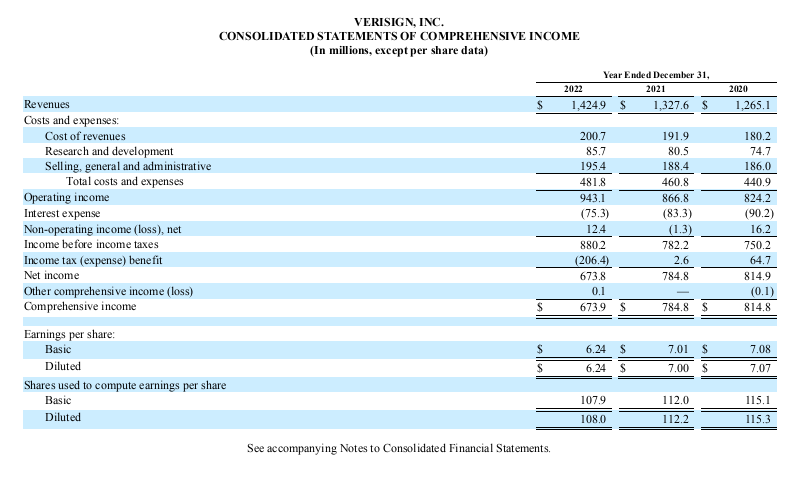

Take a look at Verisign’s financials. They are really simple.

The balance sheet is also fantastic. Domain names are prepaid so there is big negative working capital.

Ok. That’s enough for today.

In Part 2, I’ll give my breakdown on its business model and the three factors I think matter going forward. And why I think Berkshire invested.

Cheers, Jeff

———–

Related articles:

- A Breakdown of the Verisign Business Model (2 of 2) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Factors Will Determine the Future of Verisign Inc. (Tech Strategy – Podcast 191)

- A Strategy Breakdown of Arm Holdings (1 of 3) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- n/a

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Verisign Inc

Photo by Joshua Sortino on Unsplash

———

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.