Last week, I wrote about how mindless behavior, chemistry and habits can be demand-side competitive advantages, which I put under the catch-all title of “share of the consumer mind’. It’s a Warren Buffett term and one of the concepts in the Concept Library.

I described demand-side (or revenue-side) competitive advantages this way:

“…competitive advantages on the demand side (sometimes called revenue advantages). These are structural advantages that enable premium pricing, repeat purchases, higher ROIC and / or stable marketshare over longer periods of time.”

I described “share of the consumer mind” as a complicated catch-all for consumer behavior that can result in this sort of competitive advantage. We can see it in companies as varied as Bic Pens and Heinz ketchup. Continuing…

“I don’t really use the term “brand value”. I don’t really think about brands much at all. They’re just assets, like a factory. They are intangible assets that you can buy (by spending money over time).

The power is in their capture of the consumer mind. That’s the real intangible value. And this can be by emotional impact. It can be the creation of habits. It can be a chemical addiction. There are lots of mechanisms. This is all about what happens in the brain of the consumer.”

I gave examples of 7-11 and toothpaste for habit formation. And Bic pens for mindless behavior. But along the way, I also mentioned chemistry as a mechanism. I thought I should talk about that a bit before getting to my “so what”, which is that combinations of competitive advantages are what really matters.

Doubling Down on Caffeine and Sugar

Often when analysts talk about brand power and brand equity, they will point to a price premium as evidence. A particular product can charge 10% more so it has a a higher ROIC than a competitor (i.e., a higher revenue on same cost and capital structure as a competitor). Premium pricing is a metric that can show a competitive advantage on the revenue / demand side. Hamilton Helmer has this as one his 7 Powers, which he calls Branding (Feeling Good).

However, I think premium pricing reflects a are sub-case of share of the consumer mind. You can have a competitive advantage without being able to premium price. Competitive advantages are about defensibility, which may result in a higher than normal ROIC. Or it may just result in a stable, protected business with lots of repeat purchases. Some competitive advantages get you wealth generation. Some just get you wealth preservation. Defensibility doesn’t necessarily get you attractive economics. It just means you are highly defended, which can show up in stable market share and repeat purchases without having a higher ROIC.

A company with a competitive barrier and attractive unit economics can be a wealth generator (which is the case people usually talk about). But a company with a competitive advantage but weak unit economics may just be wealth preserving. A nice hotel on the beach may not create wealth, but it can protect it. Same with capital intensive utilities. The economic value per share may not increase over time but it won’t decrease because it is defended from competition. That can be a good investment if you buy with a margin of safety. Warren Buffett invests in utilities this way. It’s wealth preserving, not generating.

The metric I like is stable market share over time. If nobody can take 10% of a business over like 5 years, then it probably have some degree of protection. If the marketshare swings 20% every year (hello smartphones), it is probably not protected. However, if it is shifting between 4-5 leading players than it is probably protected from smaller players but not a group of rivals (hello auto sales in China). I think this is why Buffett bought all the airline stocks a few years ago. They had a degree of protection from smaller rivals but not each other. So he just bought them all. However, he later sold them all.

Which brings us to chemistry as a way to achieve share of the consumer mind. Some of the big mechanisms are caffeine, nicotine, sugar, salt, and fat. McDonalds is loaded with fat and salt. So do potato chips. Cigarettes have nicotine. Coca-Cola has sugar and caffeine. And Jamba Juice has jammed so much sugar into fruit smoothies it’s impressive.

There are also subtler types of chemistry in consumer products and services. Using Facebook gets you dopamine hits. Music makes you feel good. Sunshine stimulates your pineal gland and releases melatonin (which feels good). The opposite sex can make your heart rate go up. Conflict and outrage can make your blood pressure go up (hello Twitter). At a certain point, everything becomes chemistry because that’s how we work.

But I generally look for brute force (versus subtle) approaches. I look for businesses where the product is primarily about chemistry. And energy drinks are definitely a brute force approach to chemistry. Coca-Cola and Pepsi built massive businesses on it. Red Bull took it to the next level. Monster took it even farther. And 5 Hour Energy broke the bank. Every iteration puts in more caffeine and sugar, usually into a smaller amount of liquid.

From Caffeine Informer.

Coca-Cola (12 fl. oz can)

- 32 mg caffeine

- 39 grams of sugar

Red Bull (8.46 fl. oz can)

- 80 mg caffeine

- 27 grams of sugar

Black Coffee (8 fl. oz)

- 95 mg caffeine

- No sugar

Starbucks Café Mocha (12 fl. oz cup, Tall size)

- 95 mg caffeine

- 6 grams sugar

Starbucks Café Mocha (16 fl. oz cup, Grande size)

- 175 mg caffeine

- 35 grams sugar

Monster Energy (16 fl. oz can)

- 160 mg caffeine

- 54 grams of sugar

For those who aren’t familiar with Monster, it is basically like Red Bull in much bigger cans. And it comes in lots of colors and flavors.

But to be fair, 5 Hour Energy and Starbucks are still the caffeine champions.

5 Hour Energy (1.9 fl. oz can)

- 200 mg caffeine

- No sugar

Starbucks Brewed Coffee (12 fl. oz, Tall)

- 229 mg caffeine

- No sugar

Starbucks Brewed Coffee (16 fl. oz, Grande)

- 308 mg caffeine

- No sugar

An Intro to Monster Energy (MNST)

Monster sells +50 types of Monster Drinks. These are all those colors and types you see in the stores. And they are distinctive because they are in really big cans. The company does carry other brands in energy drinks (NOS, Play, Predator), coffee, water and other sub-sectors. But most of their revenue comes from the Monster brand.

They sell to bottlers and full-service beverage distributors. So they are in the syrup and marketing business, which is global with great economics. And they are not directly in the bottling and distribution business (which is capital intensive, regional and with less attractive economics). Again, this is the same split we see at Coca-Cola between its core business and its bottlers / distributors.

Monster’s beverages are available everywhere in the USA. Retail, grocery stores, specialty chains, wholesalers, club stores, mass merchandise, convenience and drug stores. Getting shelf-space and good placement is critical.

There really isn’t that much more to think about with the business. The raw materials are basic (aluminum cans, caps, PET, bottles). The packaging is important but simple. For flavors, the ingredients are juice concentrates, glucose, syrup, sugar, milk, caffeine, and others.

Generally, I like energy drinks as businesses. I think they can have both attractive economics and powerful competitive barriers. They can be wealth-generators. It’s a simple product (sugar and caffeine) in a fairly powerful business model.

And the economics are attractive.

- Net Sales of $3.8B (2018). Mostly B2B with 61% to USA full service bottlers and distributors. Gross Sales were $4.43B but $0.622 goes to promotions and allowances.

- Gross Profit 60%

- Operating cash flow: $1.16B (2018)

- Op income: 33%

- The balance sheet is what you would expect. Very few tangible assets. But significant working capital due to accounts receivable and inventory.

So if this is such a simple business, how can it have such nice economics? Why doesn’t everyone do this?

Virtuous Cycle of Share of the Consumer Mind and Marketing Scale

How do you compete as an energy drink?

If you look at the Monster 10k, you will see the following list of factors:

- Pricing

- Packaging

- New products / flavors

- Promotional and marketing strategies

- Distribution

- Financial, marketing and distribution resources

- Brand and “product image”

- Taste and flavor of products

- Trade and consumer promotions

- Packaging (attractive and different)

- The attention and support of bottlers and full service beverage distributors

- Shelf-space vs. competitors.

But I think the business model is just three things:

- Popular product with captured (addicted) customers. This is share of the consumer mind, mostly by chemistry. But it’s also about entertainment / happiness (they do taste good). And some degree of habit formation. Customers often have 2-3x servings per week. I mentally think about the product as: 50% chemical and habit formation. 50% emotional. Which is enhanced and reinforced by convenience, impulse purchases and high frequency.

- Differentiated marketing, which is mostly visual. They’re all colorful cans. They try to associate themselves with happiness (Coke) or extreme sports (Red Bull). In practice, this is a lot about standing out on the store shelves. It is about the packaging. It is visual. Share of the consumer mind is one competitive advantage. Economies of scale and scope in marketing and promotion spend is the other.

- Universal distribution and power with retailers. This is about getting good visible shelf-space and being universally available. If you’re selling a mildly addictive product, you want it within arms reach of your customers at all times. This is why cigarette vending machines were invented.

- There can also be economies of scale in logistics, which can be particularly effective in fast moving consumer goods. You are constantly resupplying thousands of small retail locations and having trucks run back and forth all the time. Keep an eye out for how many Coca-Cola delivery trucks you see in a city.

- Additionally, there are cost advantages by virtue of the weight vs. cost of the product. You can ship iPhones by plane from China to the USA, but you can’t ship cans of Coke 300 miles and still sell at a profit. The weight and transportation costs are too high relative to the price. This effectively limits your competition to the local level. That’s a barrier.

Monster Energy focuses on #1 and #2 above. And they accomplish 3 via a partnership with Coca-Cola, which owns a 19% stake in Monster and cannot compete in energy drinks. Everything else (manufacturing, packaging, etc.) is by 3rd parties. Monster is a pure breed that only does products and marketing in the caffeine and sugar business.

And you can see this in their headcount.

- 3,142 total employees in 2018 (2,354 are full time).

- 2,203 employees are in sales and marketing (1,424 are full time).

You can see a virtuous cycle between #1 and #2. For example:

- A company sells 20% more volume than a competitor based on its stronger share of the consumer mind.

- This superior volume enables the company to outspend its competitor in marketing (a fixed cost) by 20%. Economies of scale.

- This is even bigger if you have multiple products (i.e., economies of scope).

- This larger marketing spend grows their presence in the consumer mind. The next year they are outselling their competitor by 23%.

- They also strengthen their position with distributors and retailers.

- They then outspend their competitor on marketing by 23%.

- And so on. They grind their competitor down year after year.

When I look at Monster, I see 4 reinforcing competitive advantages:

- Share of the consumer (mostly by chemistry)

- Economies of scale and scope in marketing

- Production cost advantage related to transportation costs (via Coca-Cola)

- Economies of scale in logistics (via Coca-Cola)

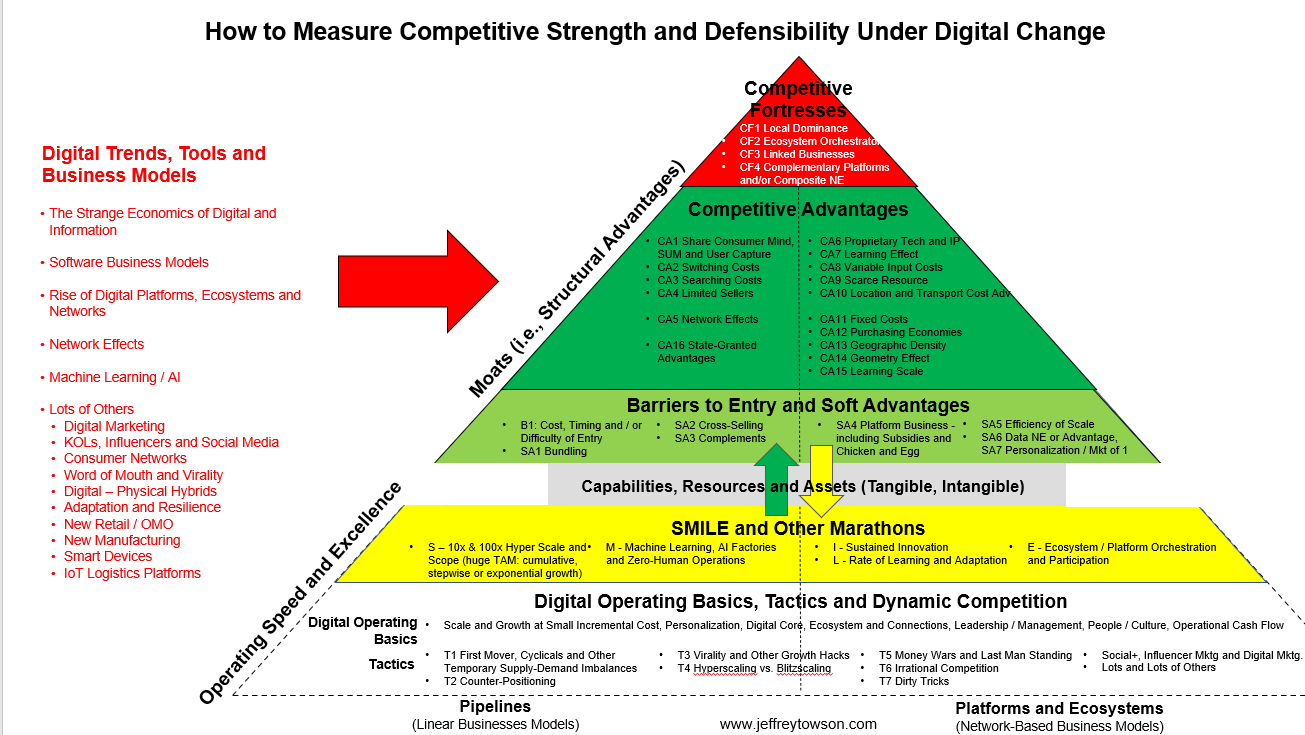

All of these are located in the green level of my pyramid.

Final Question: Does This Company Control Its Destiny?

This is one of my standard questions. I think maybe it was from Tom Russo. But is this a company that controls its own destiny? Or is it at the whim of competitors and markets? I think Monster does.

Cheers, jeff

———

Related podcasts and articles are:

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Competitive Advantage: Share of Consumer Mind

- Competitive Advantage: Economies of scale and scope

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Monster Energy

- #24: Share of the Consumer Mind in a Digital Age

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.