This week’s podcast is about political risk in China tech, but really it is about how to think systematically about the role of the State. And about how to make investment decisions on uncertain terrains.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

Here are five investment approaches to uncertain environments.

How to assess the role of the State and political risk:

- Question 1: Does the State have an active role in this sector?

- If so, don’t go forward until you can understand it. It is one of three key forces.

- If no role, then you can view this with a typical industry approach.

- Question 2: If there is an active role, what are the State’s interests? What is the evidence for this?

- Is it actively supporting?

- Is it against against rapid or significant development?

- Is it just muddy and mixed?

- Ques 3: If it is actively supporting, then ask how this firm is advancing the State’s interests? How is it working with govt? That is the main thing that matters.

About Giants, Dwarves and the State:

——-

Related articles:

- What TikTok Can Learn From Huawei About the Role of the State (Jeff’s Asia Tech Class – Podcast 39)

- How Tsingtao, CR Snow and the Other Beer SOEs Won Big in China (Pt 2 of 2)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Role of the State

- Giants, Dwarves and the State

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Philip Fisher

- Ben Graham

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

——transcription below

:

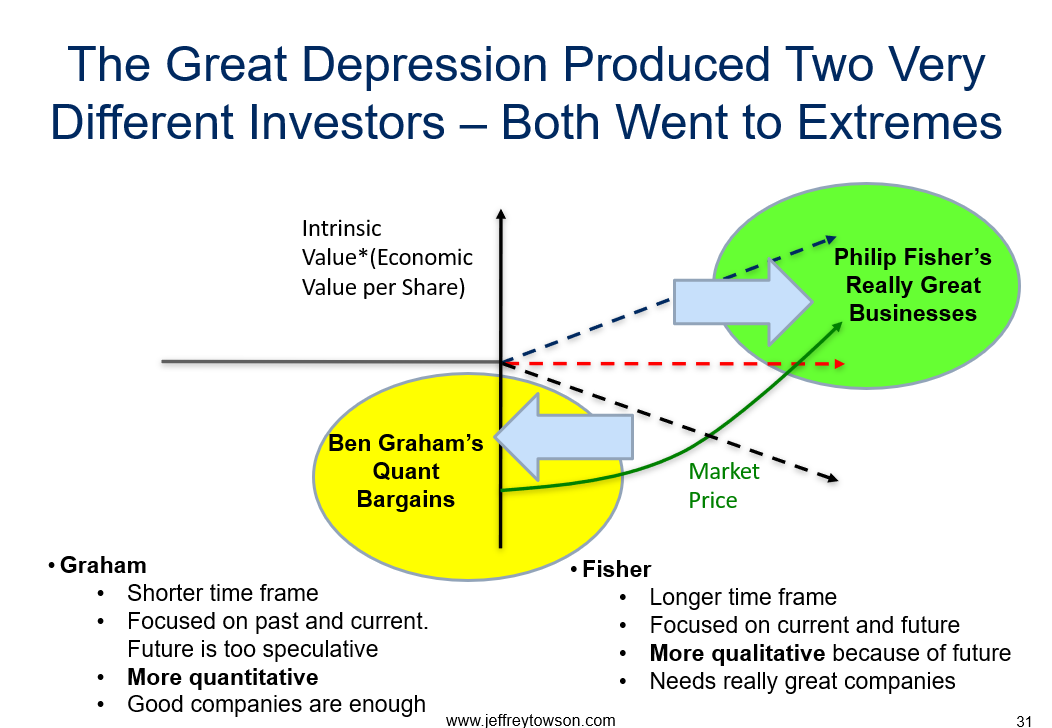

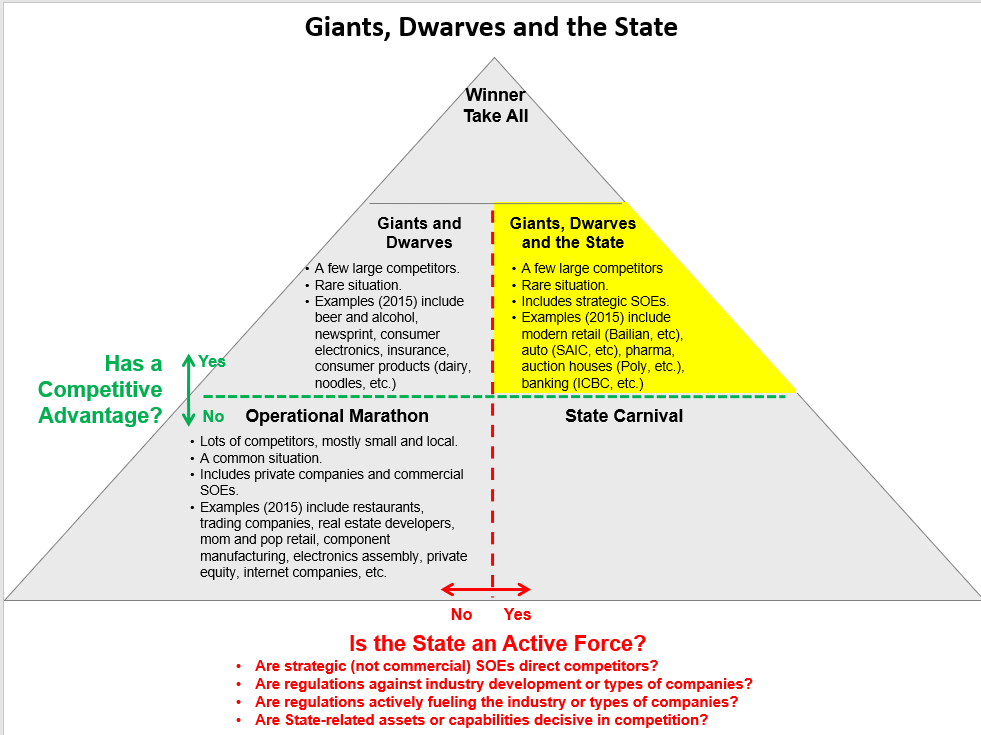

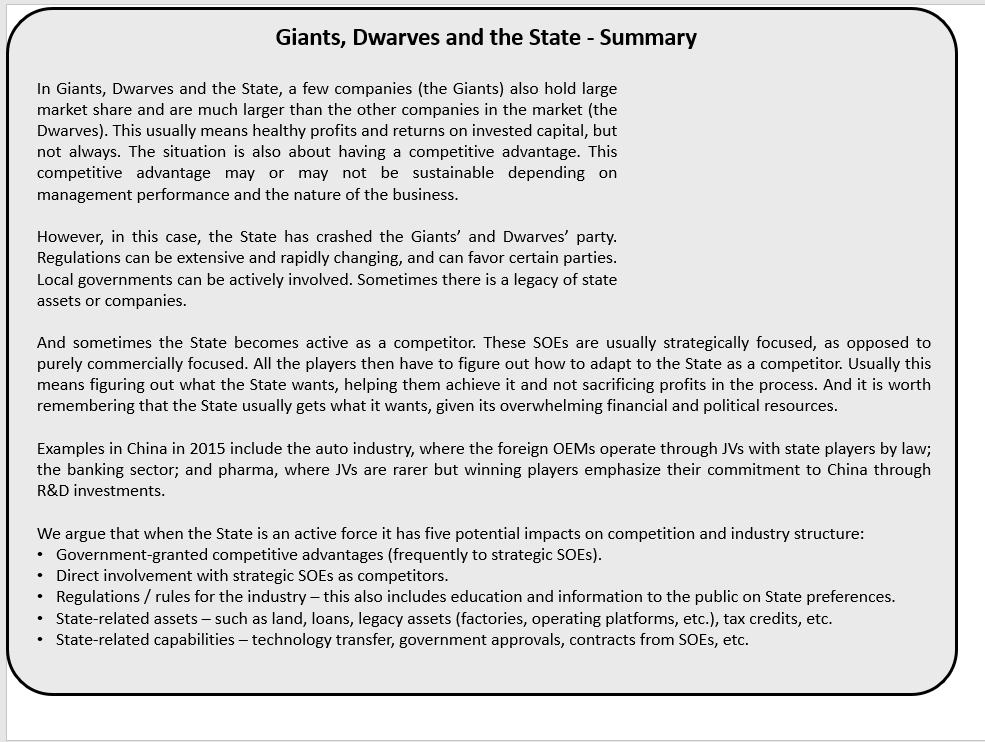

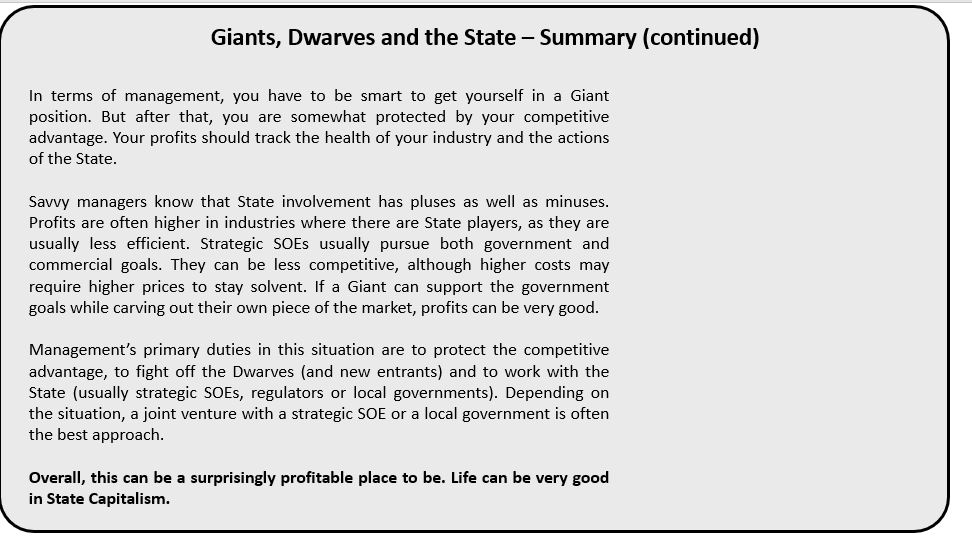

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, how to assess political risk in China tech. Now this has been a pretty decent sized issue for the last let’s say 9 months, 12 months. But last couple weeks… all over the news and it’s all over investors minds as well, which is not the same thing as being important in the news. Definitely a big topic right now. So I thought I would put forward a framework for how to actually take this apart systematically, or at least with some degree of a process that can be followed. Now for those of you who are subscribers, I’ve been sending you a bit of theory about not theory but let’s say summaries of old school investors particularly Phil Fisher, Ben Graham. Chieh Cheng Yeh, the co-founder of Value Partners in Hong Kong, sort of taking apart how they did things back in the 30s and the 40s and then sort of in China in the 1990s. Now there was a purpose to that. It was a little bit off topic because all of them were very well-schooled in how you invest amidst significant uncertainty. whether it was sort of the Great Depression era of the United States or China in the 1990s and even to a lesser degree today, they were very good at investing amid uncertainty. And the political issues is one type of that. There’s other types, but that’s definitely how it is usually viewed. So I was kind of teeing up the theory for that. I’m gonna cite a bunch of the stuff I sent you. I sent you kind of a long one on Chae Chung-ye the other day. That one’s a little bit more rambling, but I’m gonna… touch on how he has dealt with this issue. Now other content that’s in the pipeline, I’ll be sending you stuff in the next day about Ctrip. Not getting a lot of attention right now, but if you go look at Expedia.com, which is an analogous to Ctrip, their stock price has doubled, almost tripled. since about March, sort of, you know, early days of the pandemic to today. And Sea Trip is actually at five-year historical lows right now, definitely the lowest of the year. So I want to kind of talk about how do you think about these travel sites amid the pandemic. So I’ll send you that in the next day and then coming after that, based on a suggestion from one of you, which I greatly appreciated, we’re going to do Food Panda. which is kind of an interesting company. So that’s what’s in the pipeline. Okay, for those of you who aren’t subscribers, feel free, you can go over to jeffthousand.com, sign up there, free 30 day trial, see what you think. And my standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may be incorrect, no longer relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice, do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the content. Okay, so let’s sort of start with the news. Now obviously this really moved up to the next level late last year with the delay of the Ant Financial IPO. That had a lot to do with credit more than anything else and sort of the process of regulation and people wondered is this like a personal thing? Did Jack Ma make somebody angry? I don’t really know. I thought it was pretty predictable based on sort of past government actions in China regarding credit. So that wasn’t too surprising. Then we had the antitrust. regulation come down. We saw that implemented for the first time. Alibaba paid a fine, Meituan got hit, everyone started getting on their radar a bit. And then Didi went public and things sort of you know notched up a little bit more. under sort of a mix of regulatory, let’s say citations or laws, data privacy, data security, something to do with listing in the US as opposed to say mainland or Hong Kong. There was kind of a mix of issues under the whole Didi scenario. But, you know, Didi got basically pulled from the app stores, which was new. We hadn’t seen that before, really. And big surprise, we saw other tech companies jump in, because hey, if your competitor can’t sign up, anybody knew that’s a pretty good opportunity. So that was a bit of a mix, and I think people are still trying to tease apart what that was about. And then the latest one was the education technology companies. We saw some new regulations, let’s say not regulations, but discussions at very high levels with the Chinese government talking about them. in a detailed way and they mentioned a lot of stuff. A lot of stuff about really long-standing concerns about tutoring in particular, test preparation, and these private after-school companies that are I’ve been around for a long time and the government has voiced concerns about this for a long, long time. There was nothing new. The one bit that was probably new, at least I hadn’t heard it before, was this idea that these companies should be non-profit, which is kind of weird. I’ve never heard that for any company in China before. Non-profits, no one ever really talks about non-profits. So not totally sure what that means. But anyways, the stock cratered. you know, down 75% or so. You know, so there’s all this stuff sort of circulating, escalating, and you know, rightfully, a lot of investors are paying close attention. And this is how I read it when I hear them talk. And I watch all this stuff on CNBC and all of that. And I’ll be honest, none of it’s great. I’ve yet to hear too many people who I thought, in my opinion, were really on this topic in a detailed way. Generally what you hear is this sort of ongoing debate between should I stay in or should I go? That’s kind of it. It’s like two options. It seems to be uncertain maybe risky at least uncertain Do I stay in or do I exit? It’s like there’s only two options And I think that’s basically wrong if your only approach to a high See higher uncertainty environment is stay or go you need more tools in the toolkit than that. Hence my focus on Ben Graham, Phil Fisher, Chae Chung-Hye about how to invest over the long term consistently in and out, buy and hold, buy and sell in environments that are inherently uncertain and that’s just the way it is. So that’s kind of why I’ve been teeing up their strategies and I’ll go through some of those shortly here. But yeah, my take on that was. One, I’m not hearing a lot of great commentary out of the West about this. And I’m only hearing those sort of two options. So let me give you some more options. And keep in mind, I sort of went from consultant to deal person in a high uncertainty environment. I mean, I was working for a Saudi prince in Saudi Arabia, I don’t know, Lebanon, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, looking at stuff in Africa. You know, just sort of pan-emerging markets. And those are inherently uncertain. And you know, this guy, my old boss, he made his fortune in these types of environments. And one of the best ways you can deal with an environment like that is to do private deals. Because if you’re doing private deals, you can eliminate the uncertainties in the deal terms. You can go through them. Now, that’s not useful for most of you listening, but I’ll talk about that a little bit. But from a public, you know, passive investor, what do you do? But yeah, I kind of cut my teeth dealing with this sort of stuff. So it’s never really seemed foreign to me. I’ve actually always felt quite comfortable in China. You know, I kind of went from Saudi Arabian, you know, looking at busted companies in Beirut, uh, to going to China, Guangzhou and all these places. And it felt very familiar to me. That’s generally not how people. get to China. They often start in the West, maybe they start in Hong Kong, which is, let’s say, more familiar, and then they slowly move into the mainland. There’s a bit of a learning curve there. But yeah, I was always quite comfortable in all this sort of stuff. So now, if we look at uncertainty as a broader topic first, and then I’ll focus down on the political stuff. It’s a developing economy. That means by definition developing, it’s changing. The economy itself is changing fairly rapidly. Within that, consumers are changing, changing their behavior. I mean, Chinese consumers are dramatically different now than five years ago. I mean, it’s like a different world. And 2015 was different than 2010, 2002. And go back to 1995, totally different world. So consumers are changing, competitors are changing. They’re getting more sophisticated. Their capabilities are increasing all the time. You know, these are not the basic run-of-the-mill factories and banks of 2005. You get sophisticated companies now. The technology is changing. That’s kind of the whole point of this podcast. Decent amount of financial innovation. We don’t have as well developed, to put it bluntly, governance systems. There’s a lot more sort of sketchy management behavior. the line of control from your holding a piece of paper in your hand that says you own a share to the company itself is a lot less tenable. You’re not gonna sue anybody. It’s, you can’t enforce that. I mean, the lines of control that we would consider governance and ownership are a lot less secure. There’s a lot of inaccurate information for loading around, a lot of fraudulent information. Often it’s just inaccurate. I generally don’t believe anything written on a piece of paper. That’s just kind of my standard rule for China and some other companies. If it’s on paper and ink, I don’t buy it. I like to count trucks and I like to go down to the luck in coffee and count cups of coffee going out the door. I’m not a big believer in ink, generally speaking. Contracts aren’t terribly enforceable. Legal structure is not that enforceable. And then of course we get to the issue of, look, the government is actively involved in industry. It is not just a regulator. It is not like there’s the private sector and then the government regulates. No, they’re a player. They are both policemen and player at the same time. They are a participant, depending what sector you’re talking about. And that makes it very different. They can be a competitor. They can be a regulator. They can be a financier. They can be a major customer. And then on top of that, there was the idea for a long time that developing economies experienced more frequent financial crises and economic down during, certainly if you look at the 90s, you see that, Southeast Asia, Mexico, things like that. Well, now we kind of see those in the West as well. That idea got blown out of the water, with the financial crisis out of the US and then the sovereign debt crisis out of Greece and Italy. So, okay, everybody. crashes from time to time now. But generally, look, it’s just the terrain is changing faster. And now you can try and avoid it if you want. You know, well, you can kiss off half the world’s economies then, and you can just focus on, focus on, I don’t know, Germany or somewhere. Okay, so how do you deal with uncertainty? So I’ll put a slide in the show notes. Now, when I say show notes, I’m probably not clear about this. I can’t really put them in the iTunes podcast notes. So what they are is there’s a link there that goes to my website and this would be an open public page and it’ll be there. So just click on the link down below and it’ll take you over. Okay, five, really six ways, but we’ll focus on five here. Number one, stay out, just avoid it. Go with stuff that’s less uncertain. I don’t think that’s a great strategy for the world. I just don’t. I think you’re kissing off most of the world’s economy and technology is changing so fast. I mean, you know, good luck with that. Number two, you do classic Ben Graham. Ben Graham started as an investor out of Colombia in 1917, 18, right in there. You know, he begins as a statistician. That’s now a security analyst. You know, and he basically was looking at companies and writing up reports. And back then, the U.S. was a lot of utilities and railroads. So he started out looking at railroad bonds, largely because the stock market was so unpredictable. This is before the SEC, this is before people had to publish annual reports and file them with the government. Not a lot of information, stocks were all over the map, bouncing up and down all the time, fake information, a lot of the stuff I just mentioned. So bonds were considered more secure. And so bonds based on sort of heavy asset industries like railroads, utilities, and factories, he would write a lot about railroad bonds. Okay, he goes through the 20s, starts to become pretty well known. Great Depression hits, stock market crash, 1929. And he spends the next 30s and 40s and he kind of retires in the 50s after hiring a young Warren Buffett to work for him for about two years. Then he retires. Okay, what was his approach? His approach… quantitative, go quantitative. Don’t look at what might happen, look at what you can see today in the numbers today and focus on the numbers that are rock solid. So what did he like to look at? He looked at the balance sheet. Didn’t look at the income statement at all as far as I can tell. And on the balance sheet, he started at the top where the things were the most reliable like cash in the bank. Top of the balance sheet, right there, working capital. Second to that, maybe inventory. also fairly tangible, easy to check. Maybe accounts receivable. And then maybe he would go a bit further down to P.P. and E. things, but for a good portion of his career, he was just looking at net nets. He was just looking at current assets minus all the debt, not just the current liabilities, but all the debt. So that’s why they call them net nets, not just net working capital, current assets minus current liabilities, but net everything, zero all the debt, what’s left. only buy if the stock price is below basically the current assets minus all the debt. Very tangible, very highly reliable numbers or at least the most reliably numbers, quantitative approach. We look at it today, we don’t care about tomorrow. Okay, and then with that strategy, you buy in and you get out fast. You jump in and out of a highly uncertain scenario by looking at the most reliable, tangible facts today. Get in, capture your margin of safety, get out. So that’s go to option number two for how you deal with a high uncertainty environment. Option number three, Phil Fisher. Phil Fisher, interesting dude. About 10 years after Graham, he comes out of Stanford Business School. He was in the third class there. Drops out, goes to work at a bank in San Francisco. And this is sort of, you know, if Ben Graham was East Coast, Wall Street, you know, Phil Fisher was early days of Silicon Valley, San Francisco. And he developed, I mean, he basically launched his company right around the Great Depression because there was nothing else to do. He couldn’t get a job, there was no work, and he just sat in an office and read reports and such and struggled along for years and years. So both of these guys invested through the Great Depression of the US. And even before the Great Depression, if you look at the 1910s and the 1920s in the US, It was not a stable period. I mean there were financial recessions every two to three years. It was just the economy swung all over the place all the time. Now, Phil Fisher, he has a different approach, which is, they call him the father of growth investing, which I don’t really know if that’s true, but he would buy the best of the best companies, not just really good companies. Warren Buffett buys really good companies in terms of their consistency and predictability, Coca-Cola. Phil Fisher looks for Motorola. He’d look at things like Tencent. Amazon, these companies that not only are spectacularly well defended as companies, that are usually the lowest cost producer because he focused on a lot of manufacturing meets tech back then, but also have a pattern of being able to create the next product. So it wasn’t like they had one product, it’s like they create new products every three to four years and that would enable them to grow at a very high rate for decades. You’re not going to grow at a high rate. for 20 years with one product. Doesn’t usually happen. You have to be sort of a serial product launcher, product development. And that was a company like Motorola, which he identified early on and he carried that, I think he bought it in 1955 and he basically was holding that company at his death, almost 50 years just about. So now that is a very tiny subset of companies that can show that sort of behavior. And… For those of you who are subs, I sent you a note about Phil Fisher as a sort of a master of identifying rate of learning as a competitive dimension. And that’s been one of the concepts in the concept library is the increasing importance of rate of learning. Either because you’re doing one thing over and over and you get better and better at it and cheaper and cheaper at it, or type two rate of learning, you’re able to take data coming from the market and relaunch new products, which Steve Jobs was very good at. and Tip & Cook really is not. He was good at identifying the qualitative factors that let you identify companies that can do that. So Ben Graham was quantitative. Phil Fisher was qualitative. If you look at the numbers of a company today, its balance sheet, its income statement, there’s nothing in there that’s going to tell you about its ability to create product after product for decades. Technology leading products. So Phil Fisher came up with a series of questions, and I sent you kinda how he looked at that. He looked at R&D, he looked at Salesforce, he looked at manufacturing capability, and he looked at management, and how all of those things have to work together to see this. And he had very specific questions he did to identify those types of companies. Now, why would you do that in highly uncertain environments? Because if any plane is gonna see its way through this storm, it’s the best of the best. It’s the plane that’s flying over the clouds and over the storms. And his companies would just sort of, everyone else would get hit by the uncertainty, economic downturn, regulation, tech change, whatever. But these small number of companies would do better than anyone else. So this is like flying high up in the clouds. And if any company is gonna make it, it’s that company. So those are sort of two options. Option two. Buy and sell fast, get in and out, focus on quantitative certainties you can see today. Option three for a high uncertainty environment, focus on really great businesses. that are going to be able to see it through if anyone can. And that’s qualitative. It’s looking at future performance. And buy and hold those companies and sort of cruise through the bad times. In my mind, I see this flying above the storm clouds. But there’s very few companies who can do that. OK. So we can actually split the first one, Ben Graham, into two. Buy and sell fast is its own strategy. Look, if things are going to change, just don’t be in there very long. Go in and look at a company, look at a company like Didi. Decide that it’s underpriced for its potential value if a catalyst happens. Buy, wait for the catalyst. If the catalyst happens in three to six months, take your gain, get out. Or if the catalyst doesn’t happen in three to six months, get out. So you can do that sort of play. The other thing is you can look at tangible assets. Ben Graham has really two strategies. One is you can just look at tangible assets. Say, look, I don’t know what’s going on with Alibaba. I don’t know what’s going on with JD, but I know they have a massive, well, not massive, but a very large asset-based tangible fixed assets that they’ve built that aren’t going anywhere. That’s different than an education company that’s just got a bunch of teachers hired and if they take a downturn, gets let go and you know tangible fixed assets are easier to assess then you know if you’re not focused on that what are you focused on you’re focused on future performance well that’s the problem we don’t know what future performance is gonna be okay and the last option is just demand a bigger margin of safety yeah I mean if you think things are gonna change 20 30 50 percent then make sure you’re buying in with the 50 or 70 percent margin of safety between value and price The more uncertain the environment, the more risk. Make sure you’re getting a bigger discount because it gives you greater room if something goes wrong. So there’s sort of five ideas. Number one, stay out. Number two, buy and sell fast, get in and out fast. Number three, focus on quantitative certainties, tangible assets. Number four, focus on only the really great businesses. Look at future qualitative factors. Buy and hold through the bad times. Number five, demand a bigger margin of safety. and I’ve listed all those in the show notes. Okay, with that, let’s go to the political side. Now, how do you assess political risk or more, I would use the word political uncertainty in China tech? I wrote a book called the One Hour China Consumer Book four or five years ago, which I thought was really good, but no one bought it, which seems to be how it goes when I really like something that I write. But I basically said, look, if you’re gonna look at consumer China, you have to have a solid answer to three questions. If you don’t have an answer to these three questions, don’t do it. Don’t do anything. Question number one, what is the consumer demand? And you want to go micro. You don’t want these big trend numbers. You want micro. What do Chinese moms buy in Wuhan? What do Chinese husbands buy in, I don’t know, Chongqing? Micro. OK, not really relevant for this. Question number two, does it have a competitive advantage? Obviously, that’s kind of my thing. Question number three, is the state an active force in this industry? Now, that’s the one that people get stuck on. If you look at the show notes on the webpage, you’ll see I put a pyramid, because I kind of like to do pyramids, and I basically cut the pyramid into four sections based on those questions. So horizontal line cuts across it. Does it have a competitive advantage? Everything higher than that in the pyramid has a competitive advantage, everything below doesn’t. Then a line right down the center, vertical. Is the state an active force in this industry? If the answer is no, it’s to the left. Yes, it’s to the right. You wanna place this company or industry or type of business in one of the four quadrants. Now, and I’ve actually given you specific questions. in that book, but I’ll put them in the show notes. I’m going to put a bunch of slides, specific questions for how to place a business that way. First thing is to sort of think about, I’m using the word state. I’m not using the word government. In the West in particular, when you start to think about the government, it’s usually some sort of risk, like regulatory risk, regulatory change, but it’s almost like an external force after you’ve assessed the industry. When people do industry maps, They don’t put in the government. They look at the players, the suppliers, the competitors, all that, and then government is sort of considered an external force, usually. Now, if you are to the left of the line, the state is not an active force, then that would be how I view the world. Okay, we’re looking at the beer industry of China. Does it have, is the state an active force in the beer industry of China? No. even though most of the beer companies are state-owned, it doesn’t have any active role there. It doesn’t shape the industry. It’s not a player. So therefore you could kind of view it how people view this stuff in the West. It’s an external force, do your analysis. That’s a risk factor that you can put on top. And a lot of businesses are like that in China. Beer, retail, a lot of food is that way actually. Food tends to be a lot of state-owned enterprises. but the government doesn’t actually have any particular role in it. Now they have the normal government role of health and safety, but they’re not actively shaping the industry as a player, as a participant, and it really is the biggest participant. You can look at a lot of that. Retail, e-commerce, I put e-commerce in that category. If you’re buying and selling socks and t-shirts online, government doesn’t have a big interest in that. A lot of stuff, private equity. some real estate brokerage, I mean quite a few industries you can put into that category. Now if you go to the right of the line is the, does the government, does the state have a role and the answer is yes. First of all I use the word state. What does that mean? It’s sort of the authoritative power of the state which is yes it’s the government but also it’s the party. I mean keep in mind the party and the state are sort of hand in glove. in China, it’s also additional players. It can be individuals. It can be, well, in China, you’re not gonna have associations. You could have unions in some countries. In the Middle East, you’re talking princes. You’re talking about the prince’s families. I mean, it’s a larger sort of grouping than just government. So when we look at China, my question is always, what is the interest and role of the state in this business? And let’s say both of those scenarios I just gave you, there is a competitive advantage. So if I look at a company in China, like beer, and I see it’s got a competitive advantage, actually quite a few of them, and the state’s not a role, then I call that giants and dwarfs. And I’ll put the pyramid in here, and you can see I’ve sort of labeled that quadrant giants and dwarfs. The industry’s gonna have a handful of big players and lots of small players. If the state is an active player, then I call it giants, dwarfs, and the state. And that’s where, look, the state is an active player in the industry, they should be in your industry map, and they are the most important player there. And that’s actually one of the key concepts for today. I’m sorry, I didn’t list the concepts for today. The ones for today are role of the state, and giants, dwarfs, and the state. And both of those are listed in the concept library. Now, Both of those quadrants can be very attractive. In fact, I actually think it’s easier to make money in giant stores in the state than it is in giants and dwarfs. But you have to understand the role of a company in that scenario. So let’s say telecommunications. That’s giant stores in the state, it’s telco. Telco is politically sensitive. We have China Mobile, China Unicom, China Telecom, and then we have the sporting companies, Huawei, ZTE, and others. If you’re a company in that sector, the number one question is how well are you working with the state to help it achieve its objectives? That’s the number one, two, and three question. And you want to look at that. Other industries here, obviously media. Media is kind of a little bit in the middle, actually. Let’s say if we’re talking about news. News, the state absolutely has a role there. Most all of this The news organizations are either state-owned or tightly aligned. This is how ByteDance got in trouble, not in trouble, but dealt with that a couple years ago when they launched Totiao, which is a news aggregator. They were kind of doing it on their own, not really coordinating with the state. Well, the state showed up and got involved. There’s a bunch of news articles about that. Now they have tons of moderators on site that are dealing with that. We can look at credit. really anything in banking. I mean, the state has been the largest player in banking in China forever. The banks are state-owned. When you look at a state-owned entity, you kind of got to ask yourself, is this operating as a strategic entity or a commercial entity? Beer companies are commercial. Yes, the state owns them, but there’s not much involvement really. Banks are strategic entities. They are extensions of the state into the economy. That’s why lending rates change. Where the… Loans go, they often go to local state-owned enterprises that do development. Now those are extensions of the state. So if you see any company doing a lot of stuff in credit in China, which Ant Financial tried to do, I mean, red flag. You know, the number one question though is how well is this company coordinating with the state? That’s the number one, two, and three question. So we can see stuff like that. Education. I can remember back 2015. I was looking at a lot of these education tech companies, Tal, New Oriental, Leo Lishuo, 51 Talk, VIPKid, all of these companies, because it was kind of like, ooh, EdTech is gonna be the big thing, and what companies would always point to was the big spending by Chinese families, parents. I mean, the money’s huge, and that’s what everyone will point to. So that’s sort of, like I just said, you gotta answer three questions. consumers, competition, role of the state. Okay, that’s the consumer answer. What’s the competitor answer? Well, you can take that apart. What’s the role of the state? That’s the one everyone’s glossing over. And I mean, I was hearing this 2016 when I was looking at them that the government was really uncomfortable with what they were doing. And they were announcing it, they were very open about it. That here’s the funny thing about the whole education thing. What is the government’s number one concern with education? It’s that children are working too hard. That’s the number one. That kids are spending their Saturdays and Sundays doing extra after school classes and tutoring and then working like crazy through the weeks. They’re trying to dial back this maniacal focus on education and really competition that’s in lots and lots of families. We used to talk about this when I was at Peking University. Students are just burnt out by the time they get to college. So that’s one of their biggest things. So this idea that they’re gonna clamp down on education tech companies, this has been around for five years. Nothing new, nothing new in Ant Financial. When you ask people these sort of three questions, consumer, competition, role of the state, everyone gets focused on consumer because the numbers are big. People underestimate the competition because the competition’s brutal. That’s why I focus on competitive advantage. And then either they gloss over the role of the state or they get into conspiracy theories about it. But you wanna take apart that third factor as scientifically as you did the other two. So let me sort of give you the so what for this podcast. How do you assess the role of the state in China tech? Now I sort of teed it up as how do you assess political risk? I don’t think it’s the right question. How do you assess the role of the state in China tech? and the uncertainties that that necessarily creates. Well, here’s my three questions. You ask yourself, does the state have an active role in this sector? That’s question number one. You gotta have an answer to that question. You don’t go forward until you do. That’s one of those sort of three forces. If the answer is no, then you can kind of view this like something in the West. Hey, we’re looking at the industry. We have political risk. We have external forces. regulatory risks, fine. If the answer is to yes, then you have to look at the industry as being actively shaped by the state. They’re a referee, they’re a competitor, they’re a customer, they are the biggest player in that. And if you’ve got some competitive advantages, then you get into giants and dwarfs in the state. Question number two, if they have an active role, if the state has an active role, what is its primary and secondary interests? You’ve got to have an answer to that. And what is the evidence for this? Now, here’s the nice thing about China. The state is always pretty open about that. Actually, they usually telegraph things. I mean, it’s rarely a surprise. Usually it’s a couple years, at least six months to a year in advance, the government will start announcing if it’s going to become more active in an area or not, or if it’s going to change its approach or not. It’s usually telegraphed. I haven’t seen anything in the last year. that was a surprise. Now, what is kind of surprising is the mechanism. I’m asking you, what is their interest? Now, if it has an interest, there’s lots of ways it can sort of execute against that. That’s kind of surprising from time to time. But what is the state’s interest? That’s question number two. Where is the evidence? You gotta have data for that. And it’s really gonna fall into one of three categories. Is it actively supporting? development of the industry. Now if it is, let’s say electric vehicles right now, wind and solar really beginning in 2002, sports beginning in 2014-15. If that’s happening, that’s the mother of all catalysts. You can see small companies rocket up like you can’t believe. AI, huge supporter of AI. So if the government, if the state is actively supporting, that can be one of the best opportunities you’ll ever find. is the state against sort of rapid development. usually because they’re social issues, then you gotta understand that industry’s not gonna change. And if you come in doing a lot of tech, it’s not gonna work. And we can see a lot of examples of this. Public hospitals. People have been trying to do health tech for five or six years, and you’re taking all these apps, and we’re gonna move pharmacy and prescriptions onto e-commerce, that is still being held up. There is actually quite a lot of development in healthcare, but it’s very slow and steady because of the social costs involved. So, you know, VCs that came in there and did a lot of healthcare PE and a lot of healthcare tech, it didn’t work out. A lot of farming is that way, a lot of agriculture is that way. I had a great paper written by a student years ago about the funeral service business of China. And that’s an area where the state has very… significant concerns. There’s a lot of cultural issues going on there. And that business has not moved in decades. I mean, you want to know what 2001 looked like in China, go look at those companies. So if the state is against rapid development, understand it’s not going to change. Or third option, are you getting sort of a muddy mix of pro and con? Generally, I would probably stay out of that. I would put a lot of cultural stuff in that category. If you’re talking about news, very easy to understand. That’s why there’s no Facebook, there’s no YouTube. If you’re talking about culture and entertainment, it’s a little harder to predict like gaming. You know, we’ve seen the government get involved with gaming licenses and new game approvals and what can be shown within games and what can’t. Off and on, but it’s kind of hard to predict that stuff. Entertainment tends to fall into that category. Advertising tends to fall into that category that, you know, years ago you turn on the TV in Shanghai at 1 a.m. and it was just one commercial after the next for various types of girdles and push-up bras. I mean it was all over the place. And the government eventually stopped it. They didn’t think it was healthy for society and all that got sort of dialed back a bit. So anyways, that’s question number two. If the state has an active role, what are the state’s interests? You gotta have a clear answer to that question with evidence behind it. Fortunately, it’s almost always available. Is it actively supporting? Is it mostly against rapid development or is it kind of muddy? Active supporting can be a spectacularly good opportunity. Question number three, last one. If you have a situation… where the state is actively supporting an industry. What is the company you’re looking at doing to advance the state’s interest? How is it working with the government? Is it doing it effectively? That’s the key thing. It’s not their technology. It’s not their competitive advantages. It’s their working relation to help the state achieve what it wants. And if you find businesses doing that, they can grow very, very rapidly. Facial recognition would be an example of this. There were a decent number of facial recognition companies launched in the last three to five years. One of the first products they sold were to local police forces. And those companies took off like crazy because their interest aligned with the state’s interest. And you can have opinions on that in terms of the policies in it, but you can’t deny the economics. Another company that was like this was SunTech, which I’ve actually written quite a lot about. That was sort of the first Chinese solar panel maker, founded 2002, 2003, back when the Chinese government and a lot of governments around the world were actively supporting solar. The founder of that company from, hey, I’m a new PhD in Australia coming back home to China to start this company. I’m founding the company in around 2003. He became China’s richest person in like 2006. That’s how fast. it can happen if you are sort of coordinating with the government to help it achieve what it wants. It can be really powerful. Those are my three questions. I think that’s a decent way to sort of take apart the role of the state in an industry or, as I kind of teed it up, to assess political risk. Although I think that’s the wrong way to think about it. See what you think? I think it’s better than the sort of fuzzy thinking of, well, should I get in? Should I get out? No. assess the role of the state and then sort of look at the five ways you can manage that type of uncertainty of which I’ve given you five and make the call. That’s kind of what I’m doing and the two concepts for today role of the state which you can find under my concept library and giants dwarves and the state. The companies for today are Philip Fisher and Ben Graham. I didn’t really get to Chae Chung-yeh I think I’ve sort of covered this enough for now. I’ll get into him in a subsequent podcast. As for me, it’s my last night here in Rio. I fly out to Mexico City tomorrow. It was a pretty spectacular day. Man, I tell you, there’s a lot of interesting things about Brazil. Some of it, at least for me, kind of wears on me. It’s not terribly safe all the time. You have to think about some things. A lot of stuff doesn’t work so good. And then you go out on a Sunday in Rio and it’s just spectacular. I took a long walk along the lagoon for those of you who are familiar in it. It’s, I mean, the boats were out, everybody’s out. It was great. Then you walk over to the beach, you go down Ipanema, Leblon. It’s fantastic on a Sunday. I mean, in terms of awesome stuff in the world, like top five, Rio on a Sunday, it’s got to be in the top five. It’s just the best. So anyways, I’ll probably start missing it. But yeah, I was wearing on me a little bit the last week or two. I’ve been ready to go for this whole week. And now after today, I’m like, oh, this is great. So we’ll see. Anyways, I head out to Mexico a couple of days and then in theory, I get back to Bangkok in a week, but it’s, turns out getting into Thailand is a real nightmare. I’m still trying to get the paperwork I need from the embassy. I literally have spent a month on this and I still don’t have it. So it may turn out that I can’t get back in. I mean, it’s ridiculous. I mean, keep in mind, like, they’re trying to encourage people to come to Thailand. Like the sandbox is all open, we’re open for business. And it is such a bureaucratic nightmare to get anything done. And I’ve got everything. I mean, I’m like, I got a work permit. I’ve got a basically a diplomatic visa, more or less. I mean, I am… All the boxes are checked and even for me I’ve been spending a month on this. My flight’s in six days and I still don’t have the paperwork from the embassy. So who knows, maybe I’ll get sort of screwed. I was feeling bad about that all afternoon and then I came up with a backup plan. Now I feel real good. If I get jerked around on that, I’m going to go to Greece. That’s my plan. I’m going to go sit on an island for a month or two. Maybe sort of. tramps around the Balkans a little bit. I always wanted to go to Georgia. Me, I’ll go to Georgia. So anyways, I’m thinking up backup plans if I don’t get any email from the embassy in the next four days. So now I feel pretty good about it. So anyways, that’s my week. Yeah, that’s it. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope this is helpful. If I can be of help, please don’t hesitate to reach out. But otherwise I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.