This week’s podcast is about customer capture as a competitive advantage. And how digital is really changing this type of moat.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is my new book:

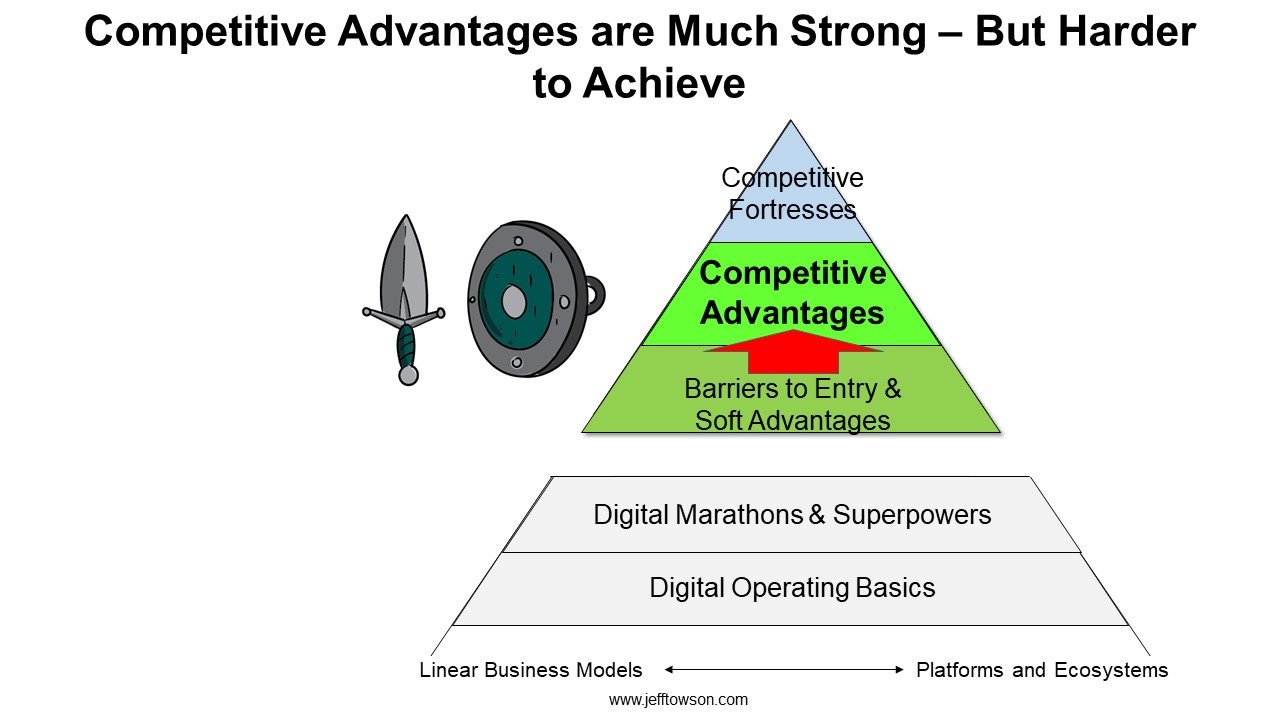

Here are the 6 levels of competition:

Here is the checklist for competitive advantage.

—–

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- CA1: Share of Consumer Mind, Share of User Mind and User Capture

- Competitive Advantages

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

Photo by K X I T H V I S U A L S on Unsplash

———Transcription Below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, an introduction to customer capture as a competitive advantage. So today is mostly theory to some concepts frameworks. I’m not really gonna go into any companies in particular depth, but it’s kind of like this is bread and butter competitive advantage on the demand side, on the revenue side, often called customer capture. But it’s really an area where digital is just changing things at such a rapid pace that I think a lot of these frameworks are becoming not terribly useful. So I’ve been spending a lot of time sort of updating what does customer capture a competitive advantage on the demand side. What does that mean in a digital business in a networked business when customers are competing when you’re doing interactions. What does actually that mean. So I’ll talk a little bit about that today and I’ll give you a framework for how to think about it. And this is coming from book number three of Motes and Marathons, which is a bunch of frameworks for how to think about competitive strength for digital businesses. But this is really getting into the heart of it, and I’m working on this right now. For those of you who are subscribers, I sent you some stuff on this in the last couple days. I think this is really where we’re getting into the center of everything when it comes to how do you measure competitive strength, competitive advantage in digital. Yeah, this is probably ground zero, so I want to talk more about that. Anyways, that’ll be the topic for today. And let’s see, standard disclaimer. Nothing in this podcast or in my writing or website is investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s just jump right into the topic. Okay, as always, we’ll start with a couple concepts. The two concepts for today. are basically competitive advantage. And I’ll kind of explain how I define that as different than say barriers to entry and other things that are often, I think, conflated with that. And then the second one is competitive advantage type number one, which we call share of the consumer mind, share of the user mind. So I’ll talk about those two. I haven’t really talked about the second one explicitly yet, so I’ll go into that. But really, I mean, the beginning here is we sort of start with the six levels of competition, which I’ll put. the graphic in the notes for this. It’s only in the notes on the webpage, by the way. It’s not in the show notes on Apple and such. I don’t really know how to put graphics in there, but you can just click over to the link and see it. So within the six levels, I’ve broken them into groups of three. The top is structural advantages and moats, and the bottom level is operating excellence. And basically, I’m looking at companies and I’m trying to figure out who is better. in terms of competition over the longer term, not short term, because stuff happens in the short term, but let’s say two, three, four years. That’s usually when these things tend to play out more, especially structural advantages. So the top three levels I call motes and structural advantages. This is, look, you’re driving a car, the other company’s got a motorcycle. You’re driving a tank, they got a whatever. I mean, it’s… It’s not about management performance. It’s not about operating anything. It’s just, look, your business model is more powerful. It’s more effective. That’s the top three levels. I talk about that as Warren Buffett land. You know, and he famously says stuff like, you want a company that’s so good that even an idiot could run it, because one day one will. The bottom three levels, which I kind of call Elon Musk land is, okay, that’s just operating performance. You’re just faster. Your operating system is better. Most of those advantages tend to be, and they’re both important. I mean, let’s not kid ourselves, both matter. The operating performance advantage usually is more transient. It lasts shorter unless you’ve got a couple longer term things, which I call marathons. But most everything in the bottom three levels is more shorter term operating performance. You’ve got to win on both levels, but you want to get at the top levels if you can. Life is much, much better. Okay, so we look at the top levels and we have three. We have competitive fortress, we have competitive advantage, and we have barriers to entry soft advantages. Now, I’ve talked about this before, but I’ll sort of reiterate it is, I think people mix this stuff all the time. Some businesses are difficult to get into. There’s a barrier. Other businesses, they’re easy to get into, but when you’re in there, you are at a structural advantage versus other players. usually an incumbent or a larger player, but not always, such that even though you can get in, you can’t win. And usually you’re just struggling to survive unless you’re the company with the dominant advantage. In some cases, we have neither of those two things. Some businesses like opening a restaurant, it’s easy to get into, just open a store down the street. And once you get in there, nobody has any major advantages, competitive advantages. So barriers to entry versus competitive advantages. Some businesses, hard to get into, like, let’s say, opening a power plant in a small town. You know, it turns out you need a lot of regulatory approval, it costs a lot of money. There’s a big first step in terms of capital. It’s not that difficult to do, but it is kind of a big first step. To get any initial users, you pretty much have to take them from an existing player because there’s usually more supply than demand. So significant barrier to entry, but once you get in, if you’re willing to pay the price, the incumbent doesn’t have anything you don’t have. And then a company like Coca-Cola, famously Richard Branson tried to launch a cola company, Virgin Cola, in the 90s. And very easy to launch a cola. And he got into the business. And then he found out that Coke and Pepsi had really major competitive advantages. They ground him down year after year. Eventually he closed shop and went home. So, and then sometimes you can have both at the same time, like a mobile carrier. Big barrier to entry to jump in. You’ve got to build a network that covers the whole country. You have to get the bandwidth. You have to get customers. It’s really difficult to jump in. And then once you do get in, you realize the incumbents have really powerful competitive advantages. Usually sort of fixed cost economy of scale is kind of the big one and you add into that maintenance and upgrade capex Because these major mobile companies are always spending spending spending to maintain the current network and upgrade Because they always have to upgrade and upgrade and upgrade so you know generally speaking in both Operating strengths and in structural advantages you can see a scenario with an oligopoly. So when people see three companies in a business, oh, there’s only Coke, Pepsi, and another one, they assume it has a competitive advantage because that is what a competitive advantage usually looks like. It ends up looking like a giants and a dwarfs scenario. However, you can have the same scenario play out with no competitive advantage. It just turns out it’s just an efficient evolution of the industry. So a lot of car companies will look the same. You’ll see a handful of big companies, but none of them really have major competitive advantages. So when you look at an oligopoly, a giants and dwarfs scenario, that can definitely be the hallmark of a competitive advantage or a buried entry or both. It doesn’t have to be. Sometimes it’s just the most efficient way for the market to exist. Everyone’s competing over time. It gravitates to a small number of big companies, but nobody’s making any money. So, I mean, but it’s a good thing to look for. Okay, so that’s kind of the basics between barrier to entry and competitive advantage. Okay, competitive advantage, much more powerful. That’s why I put them higher up on the pyramid on the six levels than barriers to entry. They are particularly powerful. The standard introduction to competitive advantage thinking usually goes something like this. If… One company is selling coffee or a restaurant, and another company across the street is selling coffee and a restaurant. How do I tell if one of those companies has a competitive advantage versus the other? And what you look for is you look for similar types of businesses, more or less, but for some reason, one company is doing things that the other one just can’t seem to match. or at least not easily or not cheaply. So Michael Porter would say, if there’s no competitive advantage, then you’re all basically doing the same activities and it’s just about who does them better. That’s operating performance. That’s Elon Musk’s plan. A competitive advantage means that you are doing activities that are different than others because they don’t know how to do them, they can’t do them, it’s too expensive to do them, something like that. but you are doing things that are somewhat different. So I’m looking at two restaurants across the street and I wanna know does one of them have a competitive structural advantage? And I can look at a couple things. I can look at their revenues, I can look at their pricing, I can look at the amount of repeat business they have, I can look at a lot of numbers. But generally speaking, you hope what will show up is a return on invested capital that is higher on one restaurant than another, even though they’re kind of relatively competing. It’s not a new entrant. This is versus a rival. Okay, if you have a higher return on invested capital, that can only really show up in one of two ways. Return on invested capital is you take the revenue, you minus the operating cost, you divide it by the invested capital, you get 18%. If one company is making 20% and the other company is making 10%, ROIC, generally the simplest explanation is either the revenue is higher for a similar business or the costs are lower for a similar business, such that revenue minus operating cost is larger than your competitor divided by invested capital. You make 20%, they make 10%. it’s argued and then they say, well, you’re either going to have demand side competitive advantages, revenue side advantages, or you’re going to have cost side advantages, of which is a couple types. There’s also government types and some other things, but that’s not a bad take. So you kind of look for an ROI-C advantage if you can see it. Now, one of the mistakes people always make about this is they always say, okay, if this has a competitive advantage, it must have a good ROI-C. Not true, not true. All I’m saying is the RIC of one company is bigger than another company. They could both be very low. Because maybe this is just not that profitable of an industry. I haven’t said anything about being in an industry that has good unit economics versus one that has bad unit economics. Supermarkets have very low profit ratios. Ride sharing, taxi hailing has very… pretty poor unit economics. But even within those businesses, you can have a competitive advantage. So it’s a relative measure. It’s not an absolute measure. That you can dominate and have tremendous competitive advantages in a not good business. Okay, but people kind of mix the unit economics up with the competitive advantage. But it’s still a pretty good way to think about it. And you can look at those numbers. the return on invested capital of the two companies over a period of time. It’s not going to be one year, it’s not going to be six months. You got to think like at least one to two business cycles because in the short term those numbers can move around a lot. Okay, the other number people tend to look at is market share stability. If you have 20% of a business of a market, 25% and it’s pretty you’re doing something that’s defendable. Especially if people keep trying to take your business, or they keep trying to take market share and they can’t do it, that’s pretty good indication that you have some degree of structural advantage. Usually between those two numbers, market share stability is a better number to look at. Now, when you think about market share stability, one of the things to think about is, no business is a complete fortress. almost entirely. So you’re really looking for the degree of market share shift per year. Does 5 to 10 percent of the market share shift between players, rivals in a year? Is it 10 percent? Is it 15 percent? That is totally common in something like mobile phones, movie studios, cars, or is it more like 1 to 2 percent? And then you can kind of, that’s a good way to approximate if you want to determine if a competitive advantage is decaying, going away, well you can look at how much market share shifts per year and then say, okay, it’s 2% per year, so at least I have 5 to 10 years worth of market share protection here, because even if it keeps going down, they’re still strong. You can kind of estimate the slope of the curve a little bit by doing that. It’s not a bad trick. Okay. So… Anyways, those are kind of the two standard numbers you might think about. ROIC versus competitors and market share stability versus competitors. Mostly talking about rivals, big rivals, small rivals, and then also new entrants. The one caveat you have to put on all of this thinking is substitutes. Are there acceptable substitutes for what you’re selling? Like restaurant, acceptable substitute is buy food and take it home. Now, if that’s the case, you really have to think about how that impacts market power. And it’s really a big deal. Like I’m convinced, like Warren Buffett, one of his major things he looks for is the absence of low cost substitutes. Everything he likes to buy, well, not everything, but a lot of the companies he likes to buy, like he bought the Apple and he bought into Apple iPhones. There is very few substitutes. They’re rivals. They’re different types of smartphones. but there is no substitute for a smartphone in this world. You have to have it. There’s nothing else you can use to replace it with. Shoe companies, things like that. He does housing. I’m convinced like low cost substitutes is one of his major things. Anyways, okay. So that’s the basic idea for, let’s call it, competitive advantage versus barriers to entry. Those are levels two and three on my six levels of competition. JPEG is in the show notes. Now also in the show notes, you will see that I have listed out 15 types of competitive advantages. And this is really the list I use. I’m not going to go through all of them, because I would take a long time. In fact, I’m only going to go through the first one. But I want you to look on the left side of the graph. It’s that green layer, that green level. And on the left, you can see 12345, which I have labeled CA1, CA2, and onto five. That stands for competitive advantage. There’s five of them. All of those I consider revenue side or demand side competitive advantages. These are ones that it’s not that you’re cheaper. It’s not that the government gave you something special. These are ones where you are charging a premium. You have… level of repeat business, but it’s showing up in the revenue idea between revenue minus operating cost divided by invested capital, that’s your ROI. It’s impacting the revenue of one restaurant versus another. And the five I’ve listed are share of the consumer mind and some other stuff on that one, which is what I’m going to talk about, switching costs, searching costs, limited sellers, and network effects. Now I’m going to This is what book three is all about. It’s sort of detailing all these. But these all show up on the revenue side, or what I’m going to increasingly say is the demand side. Now, all of this is also often referred to as customer capture. And that’s an important term. Customer capture, my standard example is you go through the airport terminal, you go through security. As soon as you’re through security, you’re a captive customer. all the stores can charge pretty much whatever you want. It’s absolutely getting outrageous. Like if you go into the US and you’re in an airport terminal and you go through security, the prices are obscene now. Like, and if you get delayed on, I actually think like there needs to be regulation because you can get delayed for a flight for eight hours, not under your control stuck there. And I mean, they’re charging like $12 for a little sandwich now. I mean, they’re absolutely out of control. But that’s a type of customer captivity, and there’s various types of customer captivity, which you could say CA1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are all various types of customer captivity. So these words revenue side, competitive advantage, demand side, competitive advantage, customer capture, it’s all kind of the same thing. Okay. Now Let’s talk about CA1, and the language here is very, very specific. I thought about it for a long time, because I’m teeing up the idea that, look, this is different when you start to go digital. And as the world goes to more software and such, CA1, which is share of the consumer mind, is starting to be very different than it was. If we’re talking about buying a can of Coke or a Snickers, share of the consumer mind, which is… an old Warren Buffett term, is you know, you have some degree of presence in the minds of consumers such that when they go to the store they always pick up the Coke even though there’s another soda right next to it that’s cheaper, they always pick up the Coke. Snickers, same thing. People have a lot of loyalty, they always buy it, and there’s a lot of reasons for how that can happen. The ones, examples I just gave you… are largely what I would consider mindless behavior. I have checklists for this, which I won’t go through right now, but some things you just buy in life without thinking about it. You walk in, you pick up the can of Coke, you don’t even think about it. Big pens, I like to use big pens as an example. People walk down to buy pens, they don’t even think about it. They just pick up the one they always bought. So it’s like, it’s got a share of the consumer mind, but it’s very sort of passive and under the radar. It’s just sort of, it’s not a habit, that’s a different phenomenon, but I call that mindless behavior. Habit formation is often, you know, you get someone to do something every day, it becomes wired into their brain, something like that. Chemistry can be one, nicotine, alcohol, that can create a share of the consumer mind. Emotional things, things that make you happy. I like the Avengers, I don’t know why I like the Avengers, it makes me happy. Other things don’t make me happy, I don’t watch them the moment they come out. aspirational, it makes you feel good, critical, it’s something you’re worried about. There’s various ways you can get to this idea of you have a prime piece of real estate which is in the minds of a certain segment of consumers. And it takes a long time to build that often, but it can be very powerful. Legacy brands that people have been reading their whole lives that have been around for decades can be very powerful and very hard to replicate. as a competitive advantage. So anyways, I’ve talked about this before. If you’re curious about that, go to the concept library, just click on share of the consumer mind. Okay, what I wanted to tee up is the idea is, okay, how is that different in digital? Well, the first thing I put in there, which I’ve put in the title, I called it share of the consumer mind, share of the user mind, and user capture. So I’m changing the language because, you know, we are not talking about customers like in a pipeline business model all the time now. Now we’re talking about platforms, now we’re talking about connectivity. We might be talking about consumers getting rides. We might be talking about drivers, giving rights, content creators, developers. I mean, there’s more user groups than the customers. And oftentimes your best strategy is to try and capture a share of the user mind. Content creators. Like why do people make videos on YouTube and TikTok? They make them all the time. They do them every day. They do it for years. They’re not making any money. Well, that’s a type of share of the user mind that they have made this tool, making videos on Tik TOK part of the lives of people. And there’s various things that actually the psychology of that is very, very important. Um, getting social status, getting recognition, um, the joy of creating something. There’s a lot of interesting psychology and content creators. There’s a lot of interesting psychology in developers. All these people that update Wikipedia all the time, they never get paid. Web 3.0 is based on decentralized governance where lots of people join associations and they all vote and they, you know, miners continually mine Bitcoin. You know, none of that, I shouldn’t say none of that, most of that is not just about getting money. There’s a lot of psychology going on there. There’s a lot of interesting behavior. I would put all of that under share of the user mind, as opposed to share of the customer mind, share of the consumer mind. We’ve talked about that one quite a bit. But there’s other user groups. And a lot of these very successful businesses are about capturing the minds of content creators. You know, the famous example is Facebook. It’s the largest media company in the world and Facebook itself doesn’t create any content. The users do that for them. There’s a lot of interesting sort of status games that are created to get people to play and that’s why they tee up notifications. Notifications like this is like it annoys me to no end. Anytime you log into an app they say give us authority to turn on your notifications right if you’re on an iPhone. Notifications are how you create habits. So that every time you check in, you see how many people liked my comment, then you post some more. That’s habit formation. So notifications are a big part of that. News feeds are very good at creating habit, sort of habit-seeking behavior. So there’s a lot going on, but I mean, the point I want to sort of hit home is like, you gotta stop thinking share of the consumer mind, share of the customer mind. You wanna think share of the user mind. And that’s really where I think a lot of the strength of a lot of these companies are. Interesting stuff for developers, definitely content creators, other groups. Okay, that’s sort of one difference you can start to think about. Another difference you can start to think about is this idea of users, or let’s say customers in this case, that function as a network. You know, customers, consumers in particular, are generally thought of as a demographic. We are selling to young women between 18 and 35 who live in cities who like fashion. That’s a demographic description. But I’ve kind of been saying for a couple years now that like you need to think about consumers in particular as a network. What young women say to each other on their smartphones because they’re all connected now, 24 seven pretty much, is far more important than what you say to them as a company. So we can start to think of consumers, we can start to think of developers, we can start to think about communities, or I use the term network. Okay, what would it mean to have a share of the network mind, a share of the community mind? Is that different than having a share of the consumer mind? It’s one thing to have all your marketing and all your tools targeted to get people to buy a can of Coke or to smoke 20 times a day. It’s a different thing to try and capture the psychology, the mind of a network of consumers that are all talking to each other. That becomes really an exercise of community building, which is what these Web 3.0 companies are doing. Their core skill in many cases is community building. So what does that mean? Networks versus population. So… You know, I’m kind of walking around this idea of customer capture. I mean, I’ve teed up the idea that competitive advantage can be on the demand side, the revenue side, or the cost side. And you’ll notice I’ve shifted from talking about revenue to demand. Demand would encompass engagement, user activity, data, not just transactions. Revenue speaks to a transaction. We need to get people to buy more cans of Coke and we want them to pay a premium. That is describing power in terms of the transaction. But so much of what we’re doing these days is not about creating transactions, it’s about creating value such that the users engage. You know, I’ve been saying to quite a few companies in the last week, you need to break your products into two types. There are products that generate cash and margins and there are products that generate engagement. And those things are rarely the same thing. It’s often that you need both. Sometimes you get both at the same time with one product, but more often than not, it’s two different products. Okay, so what does that mean in terms of customer capture? Am I really going for higher pricing and more transactions, or am I going to more engagement and data? Would that be a form of competitive advantage? So that’s why I use this term revenue side versus demand side. Demand to me captures all user activity. Revenue is just talking about the transaction, which I think is increasingly becoming a small part of what you do for customers. You do a ton of stuff for them, and then part of that is the transaction that they do. Anyways, so that’s kind of the third bit on that. And I think that’s most of what I wanted to tee up for today, is this idea of competitive advantage versus barriers to entry. That’s concept number one for today. And then the second one is on demand side advantages. I listed five of them. JPEG’s in the notes. And the first one is share of the consumer mind, which I have expanded to this larger idea of share of the consumer mind, share of the user mind, and user capture, as opposed to just the transaction or whatever. So those are kind of the two concepts for today. Those of you who are subscribers, I did send you quite a bit more about this, but it’s basically the same idea. I’ll leave you with one little note which I’ve written about before, which I call evil motes, or really that should be evil competitive advantages, which is the idea of, look, I gave you the standard story for share of the consumer mind, customer capture and that. And then I kind of teed up the idea that like digital is changing that pretty significantly. You know, the network versus individual idea that, you know, the engagement versus the revenue idea, the multiple users versus just the consumer idea. But, you know, cutting across all of this is this very important idea, which is software is incredibly good at capturing people’s minds. You know, so many of these share of the consumer mind, share of the user mind are very crude techniques. Let’s jam sugar and caffeine into a can and make it kind of addictive. Let’s put pictures of women all over the place and the guys will look, which works by the way. No, but once you move into a digital world, the tools for capturing someone’s mind are so much more sophisticated. It’s really kind of scary. So I start talking about this idea of evil motes Where we go from every digital company out there and every company that’s going digital uses digital tools to try and create habits That’s why they keep showing you notifications because you keep checking That’s why the first thing in the morning when you we wake up you check your messages They are creating habits in your lifestyle, which we would consider share of the consumer mind There’s a more serious version of that, which we call like hijacking of consumer minds. You can make entire groups of people believe something that’s not true now. And it happens all the time. You can make entire groups of people angry. There is just a lot of what we would… I hate to say it. I think it’s hijacking of the minds. So if we start, it’s just because digital is really good at this. All these things I talk about, like, hey, you’ve gotta gather data, you’ve gotta assess customer behavior, you’ve gotta continually iterate to improve the consumer experience. Software plus data is very good at that. It’s also very good at sort of hijacking you. So the benign versions of this are like, everyone’s using gamification, points. bonuses, coins, notifications, newsfeed, push notifications, to create habits. Technology created habits. And we’ve all got them, that’s why everyone stares at their smartphone all day long. Go onto a bus or a subway and just watch people. Everyone stares at their smartphone all day long. They’ve built very good habits that get us to engage. I think that’s relatively okay. It’s just very effective. You go down the scale of the more significant stuff, we get to dopamine addiction. You know, Coke and Pepsi and Red Bull, they jam caffeine into a drink. Alcohol cells, nicotine cells. Okay, dopamine is like that. We get addicted to it, we get feedback, we do social media. Okay, that one’s not terrible, I also don’t like it too much. We move further down the path, we get into… explicit exploitation of mental weaknesses. Where we look for things where if we trigger a behavior we know the response we’re gonna get. Outrage is one of these. If you want to get people to read more you continually stimulate them in a way that makes them outraged and they will keep coming back and they’re using that trigger on people all the time. That’s pretty awful. is increasingly sort of moving into what I’d call gambling behavior, where they’re starting to give you points and bonuses, and it’s really moving into gambling. And that’s pretty bad as a business, because it really does exploit certain types of people. But we can see gamification in many companies sliding right into just full-on gambling. And the Chinese government is starting to ban this, that bingo boxes and these surprise boxes, they’re basically saying, this looks like gambling. which is right, I think that is correct. Further down, we get into surveillance, we get into misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories, and now I think we’re seeing something in the last three to four years, which is just behavioral modification on a large scale. I mean, companies are getting very good at making people believe stuff, maybe it’s true, maybe it’s not. Maybe they just want them to behave in a certain way that serves their own interests. I think it turns out if you have people glued to their screens and you have very incredibly fine control of what they see and don’t see, you can pretty much shape people’s thinking now. I mean, you can walk people down the path of certain ideas over one to two years, six months, and you can get them to believe things they didn’t believe before. And the AI is getting really good at doing this. So the argument is every moment you’re looking at your smartphone screen, you think you’re looking into something. What you’re really doing is you’re giving other people direct access to your mind, and they are shaping it. You do any search on Google, you’re not going to see a thousand responses, you’re going to see five, and they choose what five you see. So it’s a way to think about this. You could put everything I just said, the benign stuff, all the way to the really sort of scary stuff. All of that could go under the title of customer capture. I mean, isn’t that what I started with? These companies own a piece of real estate. What is the piece of real estate? It’s a share of the consumer mind. They own a piece of your mind. Well, that sounded pretty benign when I was talking about Coca-Cola, but when I start talking about mass disinformation and they own part of people’s minds, suddenly that sounds a lot more nefarious. So that’s kind of the other digital thing, but I think that’s the way we’re going. I don’t think it’s avoidable. People are going to probably have to learn to sort of steal and protect their minds from basically digital manipulation. Depending what language you use, this sounds really bad or really okay. Manipulation sounds bad. Cans of Coke and Snickers don’t seem so bad. And I think that’s it for today. So that’s kind of an introduction to customer capture as a type of competitive advantage. And in terms of digital, this is ground zero. I mean, this is where so much is going on in digital. Things are moving very, very quick. This is probably where I spend 50% of my time thinking, is this sort of customer capture question. As for me, I’m in Rio de Janeiro, which is one of my favorite places, it’s just so much fun here. I came down here after a ton of meetings in Sao Paulo, been running meetings here, but now things have slowed down a little bit for Carnival. They’re not really doing Carnival, but people are out dressed up, and it’s not the big block parties where entire streets are taken over, and it’s just big bars. Basically, entire streets become bars. And they canceled the floats, but you still see people out there dressed up in weird ways. On the subway today I was next to a grown man wearing nothing but a pink tutu. He was a pretty ripped guy but he was just walking around in his pink little tutu which was kind of funny. But you see that stuff all over the place so it’s pretty great. Always puts me in a good mood to be here. I’ll be here for another couple days, probably end of the week, and then I head back to São Paulo and it looks like I’m in Rio for another month. So it’s São Paulo, Brasilia, Porto Alegre. and just sort of rocking and rolling so it’s pretty good. Anyways I think that’s it for me for today. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope everyone is taking care and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.