In Part 1, I asked the question: Why did Berkshire invest in Verisign?

For long-term holdings, I think Berkshire looks for 4 things (among many others):

- A hard floor for demand over 5-10 years. The demand may go up. It may stay flat. But it doesn’t go down. Berkshire likes things like smartphones, furniture, homes, etc. All have a fairly predictable floor for demand.

- A competitive advantage against new entrants and rivals. Against this long-term demand, the company should do well against competitors.

- Few or no low-cost substitutes. Most Berkshire businesses (like smartphones, homes, etc.) do not have low-cost substitute products.

- Few external factors such as changing customer behavior, changing technology and government actions.

I think the goal is predictability about the downside scenario. They are looking for companies where decreasing value is not a possible outcome over 5 years. Then Berkshire can invest in one of two ways:

- Wealth creation. Buy a business that is going to likely increase in economic value per share at a fair price. So, this is See’s Candy and Apple. I can these great companies. But this is almost never high growth. It is usually slow compounding (3-5%) of increasing economic value per share. I call these steady compounders.

- Wealth preservation. Buy a business that will not decrease, even if it is highly regulated or capital intensive. This is a good place to park money to preserve its value. I think his utilities are in this area. The entry price matters more. I call these good companies.

Anything else I consider unpredictable. They may go up. They may go down. Here’s how I view it.

Verisign fits these four criteria.

- We can make an easy estimate that there will be at least 173M.com and .net websites in 5 years. And we can predict the price based on the ICANN contracts.

- The competitive advantages will be discussed below. It definitely has a moat.

- Substitutes are a concern (mobile apps, mini programs, web3). But they are not at a much lower price. And they are not replacing existing websites anytime soon.

- The changing technology and government regulations are the biggest unknown. Berkshire tends to diversify regulatory risk by having groups of utilities in different localities. Verisign definitely has concentrated political risk.

I think we can rule out a significant decrease in economic value for Verisign in the next 5-10 years. Excerpt for the political risk, which is the factor to watch.

I think Verisign is likely a “great company”. It has few capital requirements. It likely won’t decrease in value, and it can likely increase economic value per share at 3-5% per year for five years.

There are lots of other factors of course. But this is a pretty solid first pass. And we can see a similar picture with a lot of Berkshire companies.

There are 3 factors here that matter.

Factor 1: Verisign Effectively Has a State-Granted Competitive Advantage

State-granted moats are the most powerful. They can be absolute in a way a commercial moat cannot. If the government of China says there are only 2-3 mobile licenses (China Mobile, China Unicom, etc.) then that’s that.

But there are lots of softer versions of this.

- You can get preferential access to land and resources versus competitors.

- You can get subsidies that foreign competitors cannot.

- You can get government contracts.

- You can get preferential treatment by regulators and other government agencies.

In the US, this is a pretty short list. But in places like China and most developing economies, there can be a lot here. However, many of these do not rise to the level of a significant competitive advantage. Let alone a sustainable one. I usually don’t put financing advantages (like low-cost loans) on this list. I look for customer and operating advantages.

In my list of competitive advantages, I give State-Granted Competitive Advantages its own category.

Verisign looks a lot like a regulated utility. But in this case it is not regulated by the State directly. It is by ICANN, which I consider a quasi-State and multi-stakeholder private entity. And that operates with an effective monopoly.

I think Verisign piggybacks the State-granted monopoly power of ICANN. It has a competitive advantage that is exclusive by quasi-State fiat (i.e., ICANN). And it is regulated, specifically with regards to its behavior, bundling, and pricing power.

You could argue that this is not really the State. ICANN is private. But they work closely with the government. And if they were to screw up, there is no doubt the US government would step in immediately. I view them as delegated State power.

And this is how I think about it.

- How is the State going to treat ICANN (and therefore Verisign) in normal times?

- How is it going to team ICANN if they screw up?

- What about in a crisis?

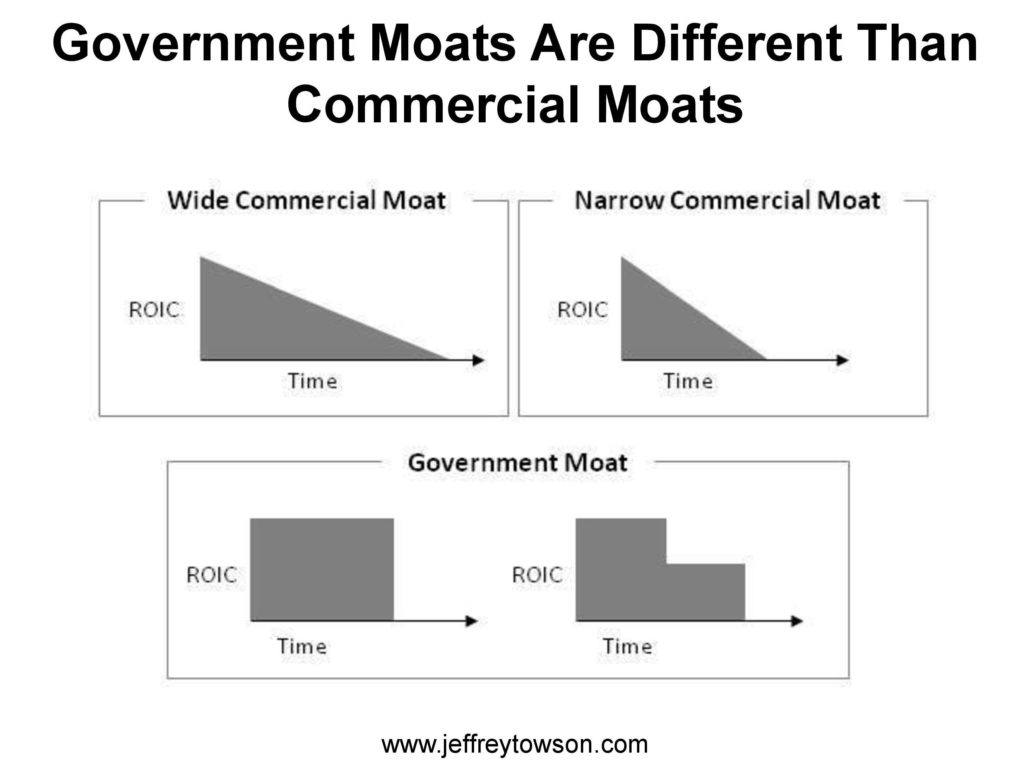

Govt granted moats are powerful. But they also tend to be binary. They can be created in a day. And they can disappear in one day. Here’s how I view them.

Factor 2: Verisign + ICANN Have a Standardization Network Effect

Does Verisign have a network effect?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot. They are in the business of providing online identities and creating trust that lowers the cost of interactions.

There is definitely a standardization network effect with verifying identity. This is similar to driver’s licenses. They are State granted (factor 1). And the more people that accept a particular type of identification (say all the stores in California accepting California driver’s license), the more value that particular form has. In contrast, fewer stores in California will accept a Thai driver license as proof of identify. So, it has less value. So that’s a network effect.

But when we go online, this becomes more of a spectrum. We can definitely see versions of online identity with Facebook and LinkedIn profiles. Note: Airbnb didn’t really work until it used Facebook profiles as a way for people to establish their identity. LinkedIn is similarly a standardized form of professional identity.

So, Verisign is a standardization and interconnection network effect. The more people that trust Verisign as an authentication for a website address, the more parties are willing to use it.

It also helps that this is for .com and .net which are used for commercial and financial interactions and transactions. When money is involved, the requirement for trust is much higher.

But I think this is fairly weak network effect. It is not a natural monopoly like language or a physical identity card. There could easily be other types of certification services for websites. There are alternatives such as Google, CNNIC, Radix, DIv, and others.

I become more convinced when you view the network effect at two levels:

- There is the standardization network effect for Verisign’s authentication of .com and .net websites (as discussed)

- The is also the standardization network effect for .com and .net domain names. These two top level domain names are what everyone uses in business and commerce. All businesses set up a .com or .net address.

I think putting these two together is more compelling. It’s really ICANN plus Verisign.

Factor 3: Technological Changes Could Create Substitutes Quickly.

This is the factor I worry about the most. The role of substitutes. Particularly those that are created by changing technological paradigms.

Verisign is a creature of the 1990’s, when websites were created. But tech paradigms keep changing and evolve. Smartphones emerged. Now cloud.

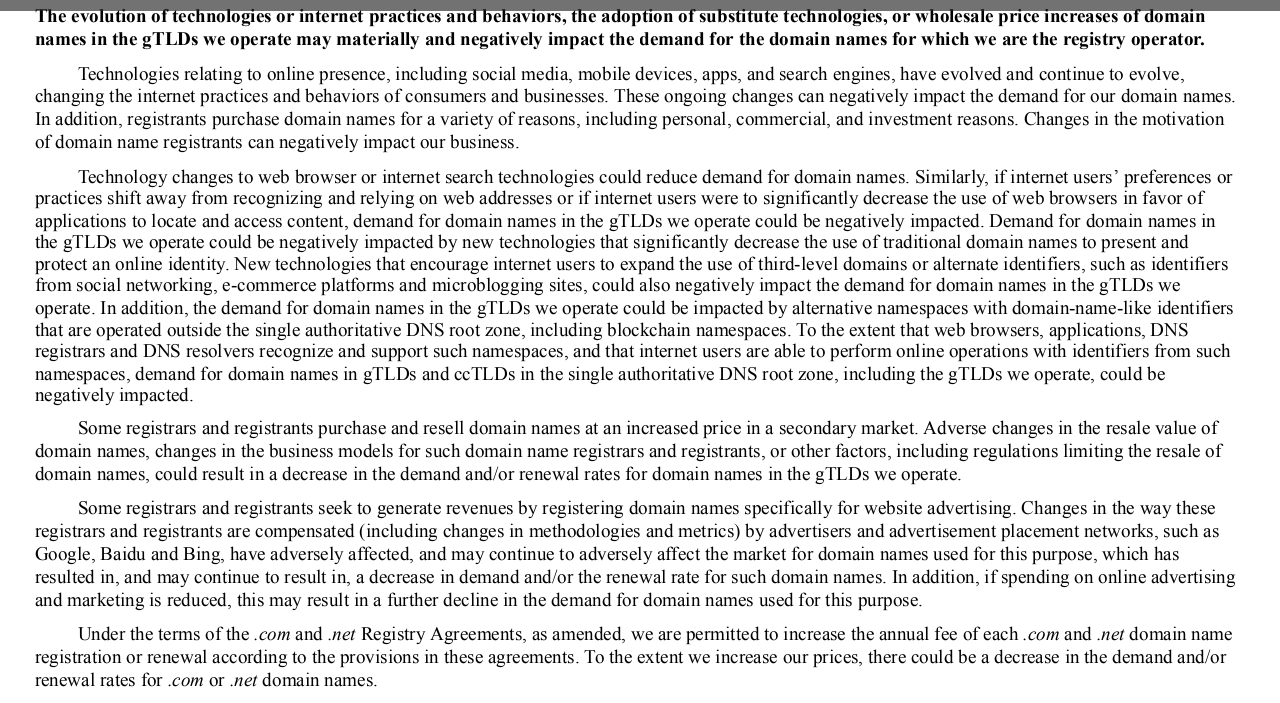

Here’s the section from the Verisign AR that got my attention. It is worth reading.

- Do mobile apps on iOS and Android operating systems need webpages? They can exist purely as apps on mobile devices.

- Do mini apps in WeChat need webpages?

- Do individuals with accounts on Facebook, LinkedIn and WhatsApp need webpages? Can’t they just interact on those platforms with their accounts there (which verify their identity)?

- Do merchants and brands who are mostly doing business on Amazon and Taobao need webpages? Aren’t their verified merchant accounts on these platforms enough?

Aren’t Amazon, Taobao, iOS, Android, Facebook, and WeChat all in the business of creating trusted online identities and interactions on their platforms?

Keep in mind, Verisign only has 173M .com and .net registrations. That is a big number. But Facebook has 3B active users.

***

That’s my take on Verisign. I like that it is a predictable cash machine that is fairly easy to understand. There aren’t that many factors to keep an eye on. It’s not surprising it’s a favorite of value investors.

Cheers, Jeff

——–

Related articles:

- Why Did Berkshire Invest in Verisign? (1 of 2) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- 3 Factors Will Determine the Future of Verisign Inc. (Tech Strategy – Podcast 191)

- A Strategy Breakdown of Arm Holdings (1 of 3) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- State-Granted Competitive Advantage

- Standardization Network Effects

- Low-Cost Substitutes

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Verisign Inc

Photo by Joshua Sortino on Unsplash

———

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.