This week’s podcast is about where GenAI and intelligence capabilities can create barriers to entry (not competitive advantages).

You can listen to this podcast here, which has the slides and graphics mentioned. Also available at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is the link to the TechMoat Consulting.

Here is the link to the Tech Tour.

Here are the slides for barriers to entry.

—––

Related articles:

- A Breakdown of the Verisign Business Model (2 of 2) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

- A Strategy Breakdown of Arm Holdings (1 of 3) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Barriers to Entry: Cost, Difficulty and Timing

- Generative AI

- Intelligence CRAs

- Grids vs. Batteries

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

——–transcription below

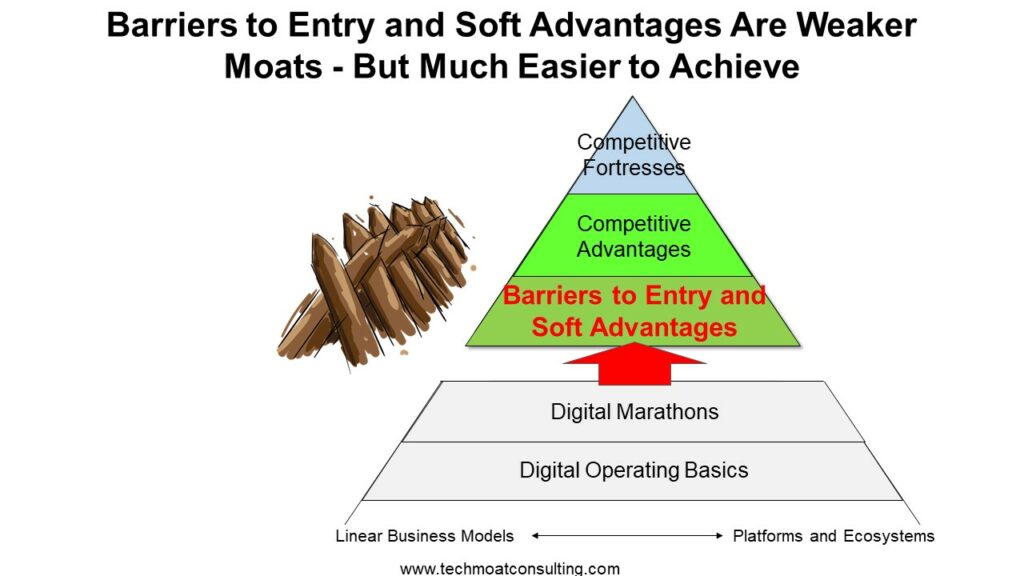

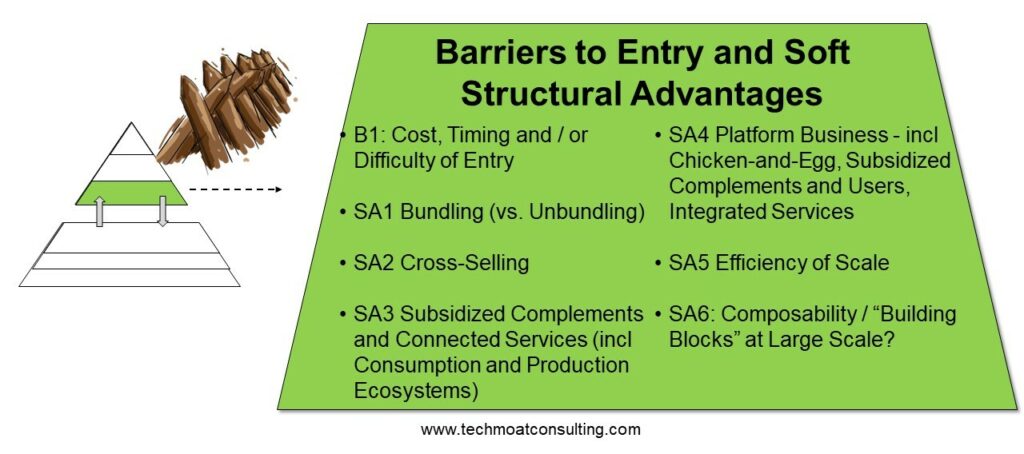

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast from Techmoat Consulting. And the topic for today, can you build barriers to entry with generative AI and really with the emerging intelligence capabilities that we’re seeing. Can they create barriers? Do you get that type of moat? And is it sustainable? That’s the question for today. Now those of you who are subscribers, I’m feeling kind of guilty. I’ve sent you, I did kind of a deep, let’s call it, strategy dive into generative AI as a strategy, moats, competitive advantages, operational advantages, things like that. And I’ve sent you, I’ve sent you nine articles, which is kind of crazy and there’s probably two more coming and then it’s done. So I think it’s good. I think it’s a very detailed framework for taking apart AI strategy. So I like that, but yeah, that’s a ton of strategy that I think a lot of you are not terribly interested in. So I’m going to get back to companies ASAP. But I do think it’s solid. I mean, the challenge with doing all this AI strategy, we’re talking about gen AI strategy, is you have to rely on sort of theory and concepts because there aren’t a lot of companies to look at. When I do digital strategy stuff, I’m probably 70% thinking about specific companies and the concepts are 30%. This is, you know, we’re the early days. So it’s a lot of more hand waving type strategy. I think it’s solid, but we’ll see. I’ll probably change it a lot going forward. Anyways, I’ll finish that up in the next couple of days and that will be that and we’ll get back to companies. I’ve been feeling kind of guilty about that all day. Anyways, okay, so let me do my standard disclaimer here. Nothing in this podcast or my writing a website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment legal or tax advice. Do your own research. Actually, there’s one other thing I need to mention. In the next day, we are going to launch a new China tour. We just did one a couple months ago– well, last month, I guess– Beijing looking fairly short, quick, but fun. A lot of four companies, a lot of fun. The next one, which is going to be in October, is sort of much more focused. It’s e-commerce and retail. So it’s for anyone who’s on that space, brands and merchants who are selling on e-commerce, which is pretty much everybody these days, it seems. And we are just going to do e-commerce in China and look at the leading companies in that area, e-commerce in retail, which really does tie into media logistics and some other spaces pretty tightly now, especially video. So we’re going to Shanghai, we’re going to Hanzhou, that’ll be in October. The itinerary, all the information on that is going up on www.towsongroup.com By the time you’ve probably listened to this, prices and all that there to. So if you’re interested in that, take a look. Yeah, it’s going to be kind of a much deeper content because we’re going to be very focused. All the company visits are going to be on that one topic. So, anyways, it’s going to be fun. Information is already up. And with that, let me get into the topic. Okay. and with that let me get into the topic. Okay, so we have a couple sort of important concepts for today that we use to pull this together. Obviously we’ll talk about generative AI, barriers to entry, which are a big deal. We’ll also talk about a new concept. It’s not really mine, it comes from Kai Fu Lee. It’s about grids versus batteries as sort of two common types of intelligence assets that are being built. I find that’s a pretty helpful concept, grids versus batteries, and I’ll talk about that. It’s basically analogy to intelligence will be like electricity. We either get it from electricity grids which are everywhere or we get it from batteries which are specialized for various situations. Okay, so there’s going to be a couple important concepts here, but I guess the first, the starting point is talking about barriers to entry, and specifically that barriers to entry are not competitive advantages. If you’ve read any of my books, you know, I kind of harp on this a lot. You know, standard Michael Porter’s Five Forces, now Six Forces. Competition, you have rivals who can be large and small. They’re in your space. New entrants, people who aren’t in your space but want to jump in. Well, you can build defenses in both places. If it’s a defense against arrival, Coca-Cola versus a smaller soda, competitive advantage. If it’s a defense about a new entrant who wants to jump in Coca-Cola against Virgin, which did jump into colas, that’s a barrier to entry. And generally speaking, barriers to entry are less powerful, I’m sorry powerful, but they’re easier to build. Barriers to entry, when I think about barriers to entry, it’s almost like I’m doing a reproduction valuation, sort of standard value investing 101, which is we look at all the operating assets of a business and we ask ourselves, what would it take to replicate the key operating assets? Now that could be factories. It could be softer things like customer relationships, could be branding, digital assets. If we’re doing a reproduction valuation, we would sort of put prices on all the operating assets that you would need to replicate a business. Well, jumping into a business you’re not in is pretty similar. We are going to have to build a choir, this key assets to jump in, This key assets to jump in and we’re going to have to get enough volume of business to be at what we call a minimum viable scale. If you jump into the COLA business, you got to get the COLA, you got to get distribution, you got to get customer base, you got to do marketing branding, you can create the operating assets which would be balance sheet. But we’re not going to have any customers. So we’re not really a, we don’t have enough traffic that we’re a viable competitor. So we also got to think about how much money are we going to have to subsidize this business until it gets to a sufficient volume of business that we would consider it viable. So I’m usually looking at those two numbers. Okay, now I will put in the show notes my standard list. Let me get back to real quick. So barriers to entry it’s a lot about looking at the assets you would have to replicate to jump. Competitive advantage, these are very strange list of phenomenon that can emerge that give you defensibility against rivals like switching costs. If I have locked all of my customers into long-term contracts like a storage facility, they’re not locked in too much, but they don’t want to switch all their stuff to another storage facility. That’s not really about the assets, it’s not really about, it’s just sort of this unique phenomenon that can emerge. And so competitive advantage is we have a list of sort of strange phenomenon like network effects, switching of cost, economies of scale. Kind of quirky. They’re usually much stronger. They’re also harder to achieve. Barriers to entry easier. So I have a standard list of barriers to entry I look at. I’ll put the graphic in there. I also talk about softer advantages, which are not quite barriers, but they can create a certain amount of defensibility against new entrants. Okay, so that’s point one number one. These things are different. Now we are looking at barriers to entry that could be created if we were to build assets operating assets that are intelligent, right? So everyone’s talking about we got to rebuild businesses with intelligence all throughout them and generative AI is obviously the biggest part of that right now. Those are going to be operating assets, smart stores, apps that do things automatically, AI agents, robo taxis. So when we start to think about when would intelligence create a barrier to entry, you start to looking at when would intelligence be part of operating assets that would be very difficult to reproduce. So I look at in terms of the assets. Okay, that’s point number one. Point number two, how do you measure that? Now I measure that with three things. When I look at any barrier to entry of a business, I’m looking at three things. I’m looking at cost, difficulty, and timing. Now the first one I’ve already talked about, if I’m going to create a COLA business, I’m Virgin, Virgin COLA, jumping in against Coke and Pepsi, I’m going to have to create certain operating assets and I can put a dollar figure on those. So I’m going to have to buy or lease a factory, I’m going to have to spend a lot of money on marketing because that’s just the nature of the business. I’m going to have to try and get distribution. It’s going to cost me cash to replicate the core operating assets. So I’m almost building a balance sheet. But keep in mind there’s a lot of operating assets we would look at that aren’t going to be on a typical balance sheet like customer relationships, software, things like that. So the first thing I could do is I could look at cost. Fine. That’s pretty straightforward. That when I think of barriers to entry, that to me is if I’m going to jump into the business, how high is the wall? Well, the wall is money. So does this business take $10 million to jump into, or does it take $2 billion? Now that doesn’t mean a company can’t do it. It just limits the number of companies that can. Startups don’t typically jump into $500 million businesses. Amazon can jump into pretty much any business it wants to. You may not want to, but it could, when we look at it in terms of money, cost. The second factor I would start to look at is difficulty. Some businesses are easy to jump into. SODA is actually fairly easy to jump into in terms of difficulty. Three people can get together in a neighborhood and start a soda company almost immediately. Come up with catchy name, hire a company to create a flavor, talk to five retailers, put it in a can with some water, deliver it. It’s operationally there’s stuff to do but it’s not terribly difficult. Doing something like scientific research and creating a new drug. Well suddenly yet one that takes a lot of money but two it two, the money’s not the biggest problem. The biggest problem is getting it to work and finding a drug that works because most of them don’t. And it turns out doing the scientific trials is very difficult. Biochemistry, drug development, science, advanced engineering, making rocket ships land. If it was just about the money, a lot of people would be landing rocket ships. It’s not about the money. It’s about that it’s really hard to do it. And you got to figure out how to do it. So difficulty is actually a better metric in many ways. Now it could be difficulty of doing it or maybe just acquiring it. Let’s say I want to get, I want to build a big resort in Malibu on the beachfront. Okay, there’s a barrier, money. How am I going to get the land? Like you might be able to buy one house here, one house there. You can’t get a very big lot that covers Malibu. It’s not possible. The people who own it won’t sell. Maybe one house, two house, something like that. So sometimes the difficulty is like, look, you can’t get your hands on it. I think one of the reasons Warren Buffett bought his railroad, BNSF, it was a, it’s a railroad that covers 50% of the US, basically the western 50% and they’ve got rail lines that connect all the city all the cities and They pretty much are the only player out there really how hard would it be to replicate a national? rail network You would have to secure the land rights Through all those states, all those neighborhoods. It’s technically probably impossible to get the rights. There’s a reason that all the railroads are like 200 years old because they were built before the areas were developed and you could get the basically the land corridors. Now that everything’s developed you can’t get land corridors across New Jersey or Pennsylvania it’s next to impossible. So difficulties are really good one. The other way to think about difficulty is sometimes just creativity. If I want to create a hit Pixar movie, if I want to be Disney, anyone can spend money making the movies, but can you make a movie that people love? You know, if you spend time making music, can you make hit songs? Most people can’t. So, difficulty is a good one. Third one, last one, timing. This is, I think, Warren Buffett’s favorite. I’m guessing there, but I think it’s his favorite. Some operating assets that you would need to be competitive in a business you want to enter. There’s no way to get them quick. You can’t force the timing with money or anything else. If you want to be Coca Cola or you want to be McKinsey, you are going to have to build up a client base and a reputation over decades. You can’t just go out there and say I’m a consulting firm I want to have a big client base like me kids know and it doesn’t matter how much you spend and it doesn’t no matter how many doors you knock on the only way to get there is to have a long working history with thousands of companies and that takes decades and there’s no way around it. Coca Cola has a legacy brand for a hundred years. Every person listening to this has probably seen a Coca Cola ad every day of their life. How do you replicate that brand awareness of a legacy brand like that? You can’t do it in 18 months by putting up billboards. It’s gonna you know those things just take time so I love the timing one. Generally speaking when I look at a barrier to entry my favorite ones are it costs a ton of money. Most people it’s really hard, most people fail. And by the way, it’s gonna take a long time. Oh, and you could add on to that one more thing. And there’s an incumbent in the space who is known for aggressive retaliation. Right, and then you can look at the history, you can look at how many people tried to enter the soda space. It turns out Virgin Cola lost. They launched, they had a big marketing campaign, they had a mention on the Friends TV show. It turns out Cola has low barriers to entry. It’s actually pretty easy. However, Cola has very powerful competitive advantages. So if you want to be a new entrant, the barriers low you can jump into cola. But then you are a rival and it turns out there are very powerful competitive advantages against rivals that Coke and Pepsi are masters at using and Virgin Cola eventually closed and left this space. Okay, so that’s kind of the second concept for today. What is a barrier to entry versus a competitive advantage? How would you measure a barrier to entry point two? Now let’s switch over to the digital world and we’ll basically apply the same ideas. All right, so how does digital? Digital could be new tools have emerged. It could be new business models using new tools. How does digital change barriers to entry? And the answer is pretty much completely. Digital tools, new digital business models have been taking down the barriers to entry of incumbent businesses for 30 years. Like whenever a new business comes and people say, “Oh, it’s very disruptive.” They’re almost always saying, “Look, this is taking down the entry barrier of a very successful company.” The cable business. Let’s do need, let’s say, blockbuster video. If we were looking at blockbuster video in 1990, 1995, we would, you know, we could look at its competitive advantages, but we’d also look at the operating assets that would be difficult or expensive or time consuming to replicate and reproduce because that’s what it would take to jump in as a physical retailer. So if we were looking at barriers to entry for Blockbuster video chain, we would be talking about the global national network of stores. This is going to take you a long time, not 20 years, but it would take you several years to replicate that across the USA. That would be one of the barriers. They wouldn’t be difficult and it probably wouldn’t cost that much, but it would take time and it would cost some money. It wouldn’t, okay, what did Netflix do to that? By going online with shipping DVDs and then streaming, they turned that, they basically just disrupted that barrier to entry. It’s gone. And not only is it gone, where it’s no longer providing protection, it’s probably a liability. So your barrier to entry, this happens frequently, a barrier to entry when it gets disrupted by a digital tech, can often become a liability that you have to carry. YouTube, TikTok, I mean in 1990, if you wanted to be a media company. You needed a lot of stuff. You needed cameras. You needed a studio. You need a distribution through the, you know, either the airwaves or through the cable networks. Very hard to get. Okay. That made that all go away. Anyone with a camera phone can go on YouTube and TikTok or launch a podcast and suddenly you’re a news company, suddenly you’re a media company. You know, my standard joke is that Joe Rogan basically sat in his basement, smoked pot, chatted with his friends, and he became the next Johnny Carson, which is crazy. Amazon self-publishing, which I do, sub-stack, WordPress, pretty much anyone at the website can become a newspaper now. Newspapers used to have some of the most powerful moats of any businesses. I think maybe even if you were to make a list in 1980 of the most powerful business models by moats, the local newspaper which were almost always monopolies. New York Times, Boston Globe. They were probably on the shortlist of 10. Okay, now anybody with a sub-stackress Amazon account can become basically a publisher. All those printing presses, all those trucks delivering the morning papers, throwing them on the porch, all of those operating assets that you would have to replicate in Boston to compete with the Boston Globe, disrupted, gone. So yeah, basically digital innovation, their favorite target is barriers to entry of incumbent businesses. That’s what venture capitalists love to hit. Okay. What about now that we’re talking about generative AI? Okay, now generative AI lots of tools but really especially for those of you who are subscribers, I started talking about intelligence assets, intelligence capabilities, I called them CRAs, intelligence capabilities, I call them CRAs, intelligence capabilities, resources and assets that you are starting to build into your business. The same way Blockbuster was building stores and the same way local newspapers were buying printing presses and trucks. Okay, we are building new assets where their primary characteristic is that they have intelligence in them. Now this could be a powerful algorithm that’s good at matching what you want to watch with a short video. It could be a robo taxi going down the street and given that intelligence is going to kind of go into everything, then mostly. You kind of really have to choose the ones that you think matter these assets and that are hard to replicate. I mean, we could look at a lot of assets that a newspaper had. Most of them aren’t critical. The ones that were critical to compete were the printing presses and the trucks and a couple other things. The advertising network is huge. Okay. network is huge. Okay, so when I start to think about what are the key assets, the intelligence assets that matter? The analogy I use is from Kai Fu Li, the AI guru of China. He talks about grids versus batteries. And he basically says, look, intelligence is going to be absolutely everywhere. Just like electricity is absolutely everywhere. We don’t even think about it. It’s in every wall. It’s in every product we carry. I mean, it just runs through everything, the cables, all of it. And generally, we access electricity by one or two ways. We plug something into the wall or we have batteries that are specially made for certain things like there’s a battery that’s inside an iPad. There’s a different type of battery that might be an SCT machine or MRI. So there’s a spectrum of batteries that are generally used for specialized purposes, although there are some standard batteries as well, obviously. There’s a degree of standardization. But that’s very different than plugging a fan into the wall. When you plug a fan into the wall, it’s very standardized. You know what you’re gonna get. Okay. Intelligence is kind of the same thing that if we start to talk about intelligence grids, well, we kinda know who at least some of those are going to be right now. Who is going to build the national, maybe international grids that we all plug into, and that puts anything intelligence into everything? Well, it’s probably the cloud service companies. Baidu, Alibaba Cloud, AWS, obviously Azure, the Google Cloud. I mean, they are building the most powerful intelligence capabilities in the cloud and then connecting them to everybody’s advice. We’re basically going to everybody’s advice. We’re basically gonna plug into those. And it’s gonna give us a full suite of intelligence capabilities that are probably not gonna be very few companies. One, they’re gonna be bigger than anyone else. So they’re gonna have scale. They’re gonna have more money, more investment, more R&D. Their suite of tools is gonna be bigger. So they’re gonna have huge advantages. We would expect to see a handful of companies become the grids. Second to that, there’s this idea floating around that AI and intelligence get smarter the more that people use it. So there’s probably some degree of a flywheel or a network effect. The more people that are using the AI tools of Baidu that are specialized in industrial, the better those industrial intelligence frameworks are going to become and the more data they’re going to have. So there’s some degree of a feedback loop which electricity doesn’t have. The electricity grids, you know, they’re usually state owned. They’re just bigger than anyone else. Well, the intelligence grid, they’re going to have a scale advantage and there’s going to be some feedback loops and probably network effects. Okay, so we kind of know who they are. And you can already go to Baidu and you will just see their suite of services. They’re already offering model as a service where you can have a model that’s standard or you can start to customize it. Apps as a service where you can have their increasing list of apps for here’s a standard chatbot you can put in your website. Here’s a standard you know chat our app for running this home robot. You know, they just have an increasing suite of these standardized apps. They’re also starting to offer agent as a service, which is interesting AI agent as a service. So we already see that happening. And then Baidu, I think, has a powerful approach to this where they’re basically building these suites of models and apps and agents that are all industry specialized. So we can kind of see who they are, fine. And the question really becomes, how much are you going to standardize? Small companies, small merchants, they’re going to basically use the standardized apps and then they’re going to feed their data into it. The large companies, okay, they’re not going to do that. They’re going to start to build their own models, but they’re going to work with these companies to customize, to put in their own proprietary data, to make the models more specific to the nuances of their business. So there’s going to be a degree of standardization versus customization both in the foundation models, the apps and the data. But it’s a pretty good analogy and I think that explains a lot of what we’re going to see and we’re already seeing it. The others would be batteries. Okay, certain companies are going to build their own intelligence capabilities that are just for them. Specialized companies, companies where you need advanced and specialized intelligence. Veterinary clinics that are doing complicated surgeries are not going to just plug into Google Cloud and say, you know, what intelligence do you have that we can come in to monitor our patients, pets in this case, their recovery times, their symptoms? Well, you know, you’re going to build that on your own. So you’re going to see a lot of specialized products, especially in areas where there’s more advanced intelligence or in areas where maybe it’s not advanced but it’s just strange you know pipeline maintenance in northern Alaska. Okay that’s a very unique environment it’s very cold they got grizzly bears everywhere you’re gonna see a lot of strange niches where companies are gonna build their own because no one else builds a good one. And that’s all algorithm, that’s all app. We can also talk about specialization on the data side. If you have proprietary data, if you have data that only comes from your users, because having data that comes from users is better, it’s much more proprietary as opposed to data that’s out in the ecosystem. You might want to keep that internally. So this sort of, when I think about batteries, I think about advanced intelligence. I think about specialized niche cases, and I think about unique data situations where you’re going to be wanting to create your own capability that is specialized and largely independent from plugging into the grid. Now you will probably use a lot of grid based services as well but that’s not a bad way to think about it and when you start to think about certain businesses, a lot of times it’s very muddy, fuzzy. But in others like, you know, advanced surgery and certain things, oh, you’re like, oh, that’s going to be a battery. It’s going to be a battery. But then you think about chat bots for merchants selling on Amazon. That’s going to be just plug into the grid. That’s all you need. And now in that case, the grid might actually be Amazon. These e-commerce sites are actually creating their own AI tools and intelligence. So you wouldn’t go to a cloud-based service in that case. That’s another little interesting category to look at. OK, so that’s kind of batteries versus grids for intelligence. And let me get to the last point I’ll finish up here, which is to basically answer the question, can you build barriers to entry using generative AI and emerging intelligence capabilities? Okay. Now, to answer this question, I basically break it into three parts. When would creating a competing battery or grid-based intelligence capability, when would creating that cost too much for most aspiring new entrants. One, they can’t simply afford it or two, they just look like this is too hard of a space. When we talk about companies that can’t break into businesses, a lot of times that’s not that they can’t, they just decide against it. It’s too hard. The incumbent looks tough. It’s a lot of money. Let’s go find another opportunity. So, one, when would the cost be significant? When would it just be too difficult to achieve? And then when would it just take too long to be feasible? So, those are my three metrics again. Based on that, here’s three conclusions. Most companies that rely on grid-based intelligence are gonna have the same intelligence capabilities, which means I think the barrier to entry is gonna be pretty low. I mean Amazon, AWS, Azure, Baidu Cloud, their entire business model is to make it easy. Well, we don’t want it to be easy. We want it to be expensive, difficult, and take a long time. So if you’re mostly using grid-based intelligence, you are going to unfortunately be in a little bit of a fight with the three major cloud companies over time. You will try and create a barrier with what you’re doing using their services. They will try to make their services better and better and more available to everyone. That’s not awesome. And I think that’s consistent with the idea that, look, most technology ends up being copied and commoditized. Almost across the board. Usually barriers to entry, competitive advantages, they don’t come from technology, they come from business models or unique products. Not from tech. I think knowledge and intelligence is kind of similar. I think most intelligence and knowledge is going to end up being copied and commoditized. That will be the rule. And then we look for exceptions, not the other way around. So I would say if you’re going to be using mostly grid-based intelligence, this is conclusion number two. Companies that are mostly relying on grid-based intelligence are going to have to focus on data advantages, or they’re going to have to focus on areas where the knowledge maps continually change. So a data advantage. OK, we’re using the standard algorithm, the model, out of AWS, but we have data that is proprietary to us. Maybe it’s internal to our factories. Maybe it’s data that our users create all the time that most companies don’t have. Maybe it’s data that’s just very scarce, and those are the kind of three things I look for, proprietary created by users are scarce. If we have that, then maybe you start to think, “Okay, we have a data advantage here.” When we combine that with a grid-based intelligence capability, we’re going to have a certain degree of a barrier. An example of that would be Google Search. The fact that Google Search has users that are always searching, that’s that data that they’re getting by who is searching for what is a huge reason why their algorithm is so good. Ways, the mapping company where a lot of the data comes from the cars. I actually think having data advantages that are sustainable over the long term is pretty difficult. Data tends to get out there. User data I like. The second bucket I mentioned, I like better. Are we in a field where yes, we’re using grid-based intelligence, but the knowledge maps for our business are constantly changing? You know, the algorithm plus the data from three months ago was giving us the right answer. Now it’s not giving us the right answer anymore. Either because the algorithm has degraded in performance, which happens, or because the environment we’re looking at is constantly changing. Now in those cases, I think you can get closer to a changing environment where, yes, you’re using grid-based intelligence, but you’re specializing for-based intelligence but you’re specializing for a constantly changing thing and that’s going to be difficult for a lot of companies to copy. Not impossible but more difficult. If you’re looking at something like a translation algorithm from French to English you know that’s going to kind of become a commodity. It’s just going to be standard. Everyone’s going to be able to do it. But if you’re looking at fashion trends in the Philippines, in the villages versus in the cities, and it’s always changing month by month or at least season by season, okay, we can tailor our models and our data to that where I think using grid based is going to be okay. So those two buckets I’m looking at and I’m looking for models, for examples. Conclusion number three, last one. Companies building their intelligence based on batteries are going to have a greater ability to build barriers. I like this one. You know if you’ve been listening to me for a while I like strange businesses and niches because they tend to have completely different ways of operating. I like Warren Buffett’s e-commerce business in Omaha. What’s it called? Oriental Trading Company. They’re an e-commerce company. They’re quite successful. But they do party tricks and events and products for company events. So if you’re throwing a company party at your hospital on Friday, you go to their website. And they’ll get you 200 rubber ducks with your company name on it and a banner and lots of plastic pens and this and you can put together a crazy assortment of little items for your big company party on Friday. Now that’s a weird business and it has weird operational requirements, customers are looking for different stuff. It’s just, you know, when I talk about businesses are like animals. A lion is kind of like a tiger. It’s kind of like a cheetah. They’re all big cats. An ant eater is not like anything else. Oriental trading is an ant eater. It’s weird. It’s a porcupine Google search is a porcupine, right? These are just weird creatures their operational aspect assets Whether they’re intelligent or not tend to be highly specialized for their weird situation. I like businesses like that. I like batteries Where it’s a specialty niche Where intelligence is critical, that would be the veterinary surgery example or intelligence that’s specialized for assessing pollution in highly sensitive environments like semiconductor foundries. Something complicated and advanced where intelligence matters, but it’s also weird. If you’re using battery-based intelligence to assess the performance of a yogurt shop, no, it doesn’t work. So that’s kind of one, like I like batteries. I like when there’s specialty niches that are advanced or complicated in terms of intelligence. The other two, again, data advantages. I think data advantages will be easier to achieve in these little niches or highly specialized advanced areas. And changing and evolving knowledge maps, same thing. I think that’s more interesting for the grid-based intelligence, not the battery base anyways, those are my three working conclusions and I’m looking for more examples. I found a couple, but you know, that’s the problem is we have to I have the theory I think I got some decent frameworks for taking apart these questions, but you know Reality is always more complicated. So, we’ll see what happens in practice. Okay, that is it for today. The three concepts again, barriers to entry, measuring which are different than competitive advantage, barriers to entry, how to measure them, cost, timing, and difficulty, intelligence CRAs, intelligence capabilities and assets that are going to be built when they might become a barrier to entry. And then finally, my little framework for thinking about intelligence CRAs is grids versus batteries. I found that pretty helpful. I mean, it’ll get a lot more complicated, obviously, but for now it’s not terrible as a question. Anyways, that’s it for today in terms of the content. I’m actually, I’m sitting in Changgu Bali right now, finishing up a month in Indonesia, which has been really spectacular. Like we just had the best time. Like I’ve been to Indonesia before but it was never really my place. It’s my place now. Man we were sitting in a villa in the jungle looking out over the rice fields, getting coffee delivered in the morning which is obviously important for me. Just a wonderful time. Like really that was more in Ubud, not Chiangu is not Canggu’s sort of a beach community, not kind of my area. That was fantastic. We did like river rafting outside of Ubud which is you know going down the rap. And there were little rapids. That was so much fun. Waterfalls, volcano hiking. Yeah like Eastern Java and like Northern Bali, I think it’s kind of I’m gonna spend a lot more time here I think. So, man, it’s really been fun but I’m kind of eager to I’m pretty much done. A month is good. Anyway, that’s kind of what I’ve been doing. Pretty fantastic overall. Minus the pneumonia. Outside of that it was pretty fantastic. I also think the food is great. Like, I’m coming to the uncomfortable conclusion that food in Indonesia is better than Thailand. Which, if you had told me that I would never believe you because I love Thai food. And I just think it’s awesome. Like, it’s a 10 out of 10. I think Indonesians might be 11. Like, it’s, we’re getting like, goat stew and all these crazy dishes. And I think that’s a lot of people Like it’s, we’re getting like goat stew and all these crazy dinners and sliced fruit in spice. There’s all these crazy things we’ve been having. A lot of like pork ribs and steak. Anyways, yeah. So we’ve been spending a surprising amount of time talking about food Which is not something I normally talk about but it’s like is it better here than Thailand? Am I crazy? A little bit. Let’s call it 10% better because Thailand’s awesome, but anyways That’s been my month pretty fantastic. Anyways, that’s it for me. I hope this is helpful to everybody I hope everyone’s having a great June and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye

——–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.