I’ve recently visited iQIYI in Beijing and it has gotten me thinking about “creative China”. It’s a major secular trend that doesn’t get a lot of attention. I’ve been thinking about it for like 5 years.

Fact: Of the 19 million students in Chinese universities in 2009, over 1 million were studying art and design.

Think about that number for a moment. One million students studying painting, design and other creative arts. That is larger than the student populations studying chemistry, law, or economics in China.

Fast forward to today and all those creative students that have entered the workforce. China has a very large creative workforce. And it keeps growing. There are now millions and millions of designers, animators, and other creative professionals in Mainland China. That is not usually how people think about the Chinese workforce. What usually comes to mind is lots of people in factories assembling iPhones and soccer balls. Or maybe lots of engineers. But the rising wave of creative professionals is an important phenomenon.

Creative China as a phenomenon has fascinating implications. One of which is its increasing impact on entertainment and technology. That’s what I think about when I visit companies like iQIYI and Alibaba Pictures. And this brings up a visit I did back in 2016 to the offices of Oriental DreamWorks (ODW) in Shanghai. At the time, it was the leading animation studio in China. It was working on the latest Kung Fu Panda movie at the time. I think it is a good example of creative China. Plus ODW was just a cool company.

A Visit to Oriental DreamWorks in Shanghai

Oriental DreamWorks (ODW) was founded by Li Ruigang and Jeffrey Katzenberg in 2012. It was a joint venture between a famous Hollywood mogul (and a leading animation studio) and a few State-owned and related businesses in China. And that’s how you do entertainment in China. You have to operate by partnerships with SOEs.

DreamWorks’ Jeffrey Katzenberg had long been ahead of the curve when it came to China. Prior to DreamWorks, he was the person who created Disney’s film Mulan, the first animated movie based on a Chinese character. And prior to that he was the studio executive who approved The Joy Luck Club, the first major Hollywood movie about Chinese-American families. Around the same time, he was also responsible for creating a Disney internship program that brought some of the first Asian-Americans into the Hollywood studio system.

According to Peilin Chou (then creative head of Oriental DreamWorks), “Jeffrey[Katzenberg] has always been a visionary who understood that a great story is a great story. And regardless of the culture, audiences worldwide will tune in for a great story. In addition, he has always had a genuine passion and love for China.” Chou, now in charge at animation at Netflix, was one of the first four interns selected for Katzenberg’s internship program back in 1994.

The other co-founder was Li Ruigang, then head of China Media Capital. Li had long been at the forefront of creative China and the “partner of choice” for Hollywood projects in China. He had previously run Shanghai Media Group and left to create a private equity group that arranged and invested in Hollywood-to-China projects. He also provided a great quote for our first One Hour China book.

ODW’s offices were in the Xujiahui district of Shanghai. In 1990, Shanghai was officially planned as a shipping and a finance city (like New York). But the government plan for the city was updated in 2010 to add entertainment. Shortly after, Shanghai Disneyland was finally approved. And ODW deal was also done shortly after. And much of this new entertainment activity was happening in Xujiahui. Even today, much of the gaming industry of China is in this part of town.

So it wasn’t a surprise that ODW had spectacular offices in Xujiahui on the Huangpu River. My first conclusion when I arrived was that the people behind ODW were either really good at Shanghai real estate or they had tremendous guanxi.

At ODW’s offices, I interviewed their then creative head Peilin Chou and got a tour. Walking around their offices, you could see their animators (they call them artists) working in teams on everything from story ideas to designing the hair and surfacing of various characters. Overall, it’s impressive – but as a finance creature I always find the whole creative process a bit of a mystery.

My discussion with Chou mostly focused on their creative professionals. That was my interest. I wanted to know where they came from and how they work together to create animated films. China didn’t even have animation schools ten years prior. And now ODW was producing a level of quality mostly unmatched in China for animation. The key to this appeared to be how they combined young Chinese artists with imported Hollywood technical expertise and experience.

At the time, ODW had about 250 staff total, with the creative team having about 150 artists and animators. Their artists were +90% native Chinese, and were mostly trained at China’s art and design schools. The staff overseeing project development were about 50% native Chinese and 50% Chinese-Americans with Hollywood experience. So was a hybrid “best of both worlds” approach.

Some of ODW’s creative heads. From left to right, Lulu Zhao (Manager of Creative Development), Susan Xu (Creative Development Coordinator), Justinian Huang (Director of Creative Development), Peilin Chou (Head of Creative for Feature Animation). Photo courtesy of Oriental DreamWorks.

The first major work by ODW was Kung Fu Panda 3. It became the top grossing animated movie in China at that time. And it was a compelling example of what world-class movies, made mostly by Chinese talent, could look like. The characters spoke fluent Mandarin and the story was full of cultural subtleties that foreign audiences probably missed. The movie stood out as both high quality but also uniquely Chinese.

Art Education and Increasing Brainpower in China

Chinese education is a big part of its rising creative talent. I have long been a professor in China (Peking University, CEIBS) so I do have a reasonable view into the education system. And it is impossible not to notice the huge improvements in students over the past ten years. They have become much smarter and far more sophisticated. And they are shockingly ambitious. So the idea that there we are seeing similar advances in arts and culture is not surprising to me.

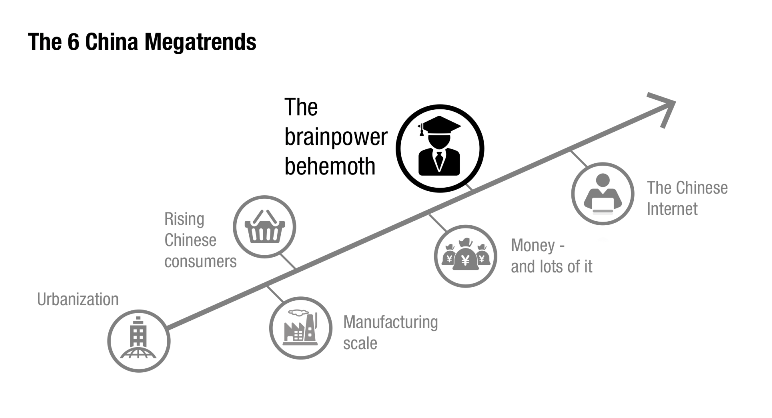

In our One Hour China book, we pointed to increasing brainpower at scale as one of the important long term secular trends of China.

As mentioned, you can describe human capital in China as having had three waves. And it is increasing in brainpower with each wave.

- Manufacturing and more basic laborers were the first wave. Starting in the 1980’s and 1990’s, millions of factory workers began producing everything from soccer balls to underwear. And this massive population of workers impacted businesses and markets around the world. The world became accustomed to the phrase “Made in China”.

- The second wave has been in engineering and, to a lesser degree, the sciences. Over the past decade, technically advanced multinationals, such as GE and Pfizer, have been confronted with how millions of Chinese engineers (and scientists) will impact their industries and business models. You can see their responses in the hundreds of R&D centers being built across China today.

- I view the emergence of millions of young Chinese artists and other creative professionals as the third wave. But instead of impacting manufacturing and engineering companies, this wave is impacting film, television, architecture, video games, industrial design and other sectors.

China’s Unusual Art Education System

The government has been the primary driver of this mega-trend.

In the 1990s, the Chinese government identified a lack of creativity as a competitive weakness for the country. This resulted in a surge in State-supported art departments and art schools. These schools also later expanded into areas such as video game design, animation, urban design, and multimedia. It has been pretty impressive. This was a top decision that really worked.

But it is worth keeping in mind art education’s strange position within Chinese state capitalism. Yes, art education is still mostly state-created and state-run. And yes, the wave of Chinese creative professionals today is mostly a result of a state-directed expansion of this sector over the past 15 years.

But the art community itself is also frequently at odds not just with the state, but also with much of modern China’s commercial ambitions. It can be a pretty unique and Bohemian community. One that tends to pride itself on unconventional attitudes, even while being largely State created.

Plus, art education in China has lots of students who are considered disappointments by their parents. According to Chou, “I have had many artists at our studio tell me their parents are disappointed with their career choice, or that their parents wished they had become a doctor or lawyer instead.” She says this is “crazy ironic given that these are easily some of the best animation artists in all of China.”

Final Question: What Does the Rise of Creative China Mean for Companies like iQIYI? What About for Hollywood?

In 2018, CMC Capital Partners took full ownership of Oriental DreamWorks and renamed it as Pearl Studio. They continued collaborating with DreamWorks on certain projects but the Hollywood partner largely exited. Frank Zhu was appointed CEO.

The rise of creative China and the launch of ventures like Oriental DreamWorks is pretty fascinating. It raises questions for Hollywood’s ambitions for the Mainland. But the bigger question is:

- What will be the impact of China’s rapidly increasing creative talent on entertainment leaders like iQIYI, Alibaba Pictures and Tencent?

- What about its impact on Hollywood? Is it a threat to studios? Is it an opportunity to outsource creativity to Asia (similar to manufacturing)?

My answer to the first is that these companies are going to rival Hollywood in ability. They have the numbers.

For the second, Hollywood studios will face the same questions that companies like GE and Samsung have already faced:

- Will having operations and production in China be necessary for winning in China? My answer is that I think it will.

- Will China operations and talent one day be necessary for winning internationally? That’s a solid “maybe”.

Overall, creative China is an interesting phenomenon that is worth keeping an eye on.

Thanks for reading – Jeff

——–

Related articles:

- Can ByteDance Breach Alibaba’s Infrastructure Moat and Become An Ecommerce Giant? (Tech Strategy – Podcast 82)

- Alibaba Takes Over Sun Art Retail. Is It Going to Take Off? Or Is It Infrastructure? (pt 1 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Update)

- Could Sun Art Grow +30% Under Alibaba? (pt 2 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Update)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Entertainment

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- iQIYI

- Alibaba Pictures

Top photo courtesy of Oriental DreamWorks

———-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.