This week’s podcast is about Monster Energy and my approach for winning in digital as a CPG brand.

You can listen to this podcast here, which has the slides and graphics mentioned. Also available at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is the link to the TechMoat Consulting.

Here is the link to the China Tech Tour.

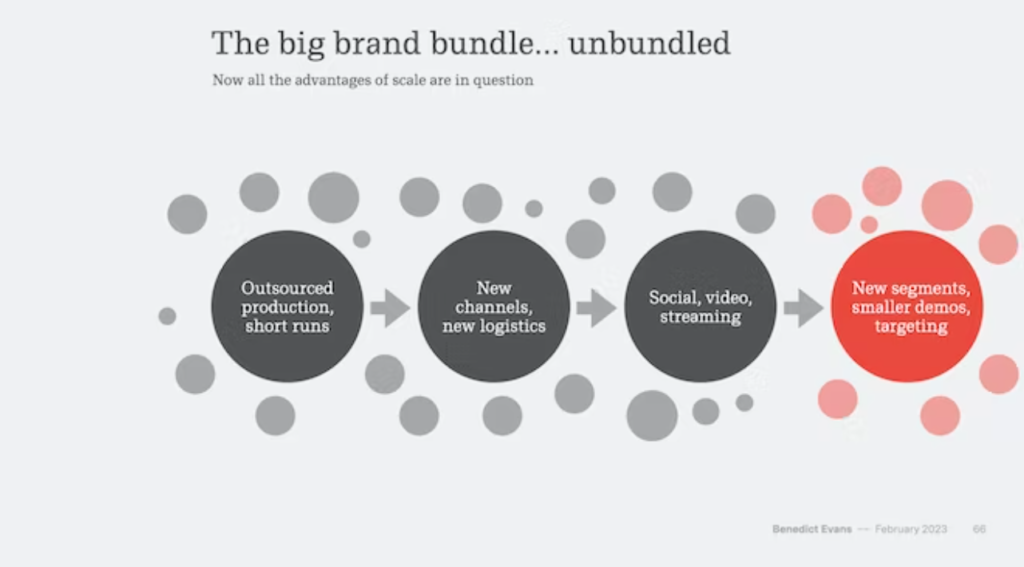

Here is the mentioned slide from Benedict Evans.

———

Related podcasts and articles are:

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Competitive Advantage: Share of Consumer Mind

- Digital Marathon: Ecosystem / Platform Participation

- CPG and FMCG

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Monster Energy

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash

——–

——–Transcript Below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast where we analyze the best digital businesses of the US, China and Asia. And the topic for today, Monster Energy and how CPG, consumer packaged goods, can win in digital. Now, I actually, for those of you who’ve been listening for a long time, a bit over two years ago, I wrote about Monster Energy. which is the big, it’s like Red Bull, but the cans are twice as big and they’re very colorful and they have a cool partnership with Coca-Cola. And yeah, I mean, it’s a caffeine and sugar business and they just basically turned it up to 11. And it’s been kind of a company that I’ve had my eye on for a long time. I thought it was a very cool company, very strong business model. I didn’t end up investing. which in retrospect was a mistake because in the last six to 12 months, it’s been one of the best performing stocks out there. In spite of all the slowdown and everything else, Monster Energy has just been going up and up. It’s up about 50% over the last two years. So one, I thought I’d talk about that business model because it’s a very effective business model. And then two, I wanted to talk more about the idea of CPG companies, FMCG, fast moving consumer goods, consumer packaged goods, these things kind of overlap a lot and how they are confronted with digital and what they should be doing. And that’s actually a pretty big question. So I thought I’d tie those two together and that’ll be the topic for today. Okay, other stuff, there is the China Tech Tour, which is coming up in a couple months. I’ve put this up on the website, which is techmoatconsulting.com, or you can do tausendgroup.com, but it’s the same webpage. And you’ll see the itinerary five days, Shanghai, Beijing, Hangzhou, visiting multiple tech companies, and basically doing a deep dive on China Tech. That’ll be the process. I know some of you have written. and expressed interest and I’ve been slow to lock down the dates which I know has got to be frustrating. I’m sorry about that. We’re coordinating with some businesses so there’s a little bit of a process thing going on but that should get locked down very very soon. Anyways, if you’re interested send me an email. My email is on the website. Very easy to find. Okay, and let’s see. Standard disclaimer. Nothing in this podcast or in my writing or website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let me get into the topic. Now, as always, we start with a couple key concepts. And the concepts for today are going to be… Share of the consumer mind, which is one of the competitive advantages. It’s actually the first one on my list. We’re gonna talk about digital versions of that, which it’s a form of basically customer capture. I’ll talk a lot about that. And then ecosystem participation, which is one of the digital marathons that certain companies can run. Those are gonna be kind of the two ideas. And I won’t tee them up now, I’ll get into them in depth. So those are the two, if you’re interested in those two. Go to the concept library on my webpage, gfthousand.com, you’ll find it there. But I’m gonna talk about those two in particular. Okay. CPG, consumer packaged goods, overlaps with FMCG, fast moving consumer goods. Some people say FMCG is just a subset of consumer packaged goods. It’s faster version of it, hence the word fast moving. But really, I mean, it’s kind of a vague. category. You know pretty much everything you see when you go into a drug store or convenience store. Generally CPG is considered sort of stuff that you buy regularly. You know this isn’t buying an iron. You know not things. I mean this is FMCG, let’s say daily consumer packaged goods, maybe weekly, monthly. You know so this is more like ketchup. house, you know, sort of processed foods, things that you get all the time, mustard, sauces, milk. So there can be sort of a whole food category in this. Household products, bleach, detergent, cleaning things, kind of stuff that you see in the typical cabinet or shelf in a home. People also talk about beauty products this way. Makeup, lipstick, shampoo. conditioners, things like that. And then health and wellness is arguably one of these as well. Vitamins, supplements, so it’s, of course, and then we’re getting talked about monster. So beverages, coffee, soda. So it’s kind of a big, vague category of consumer products as various types. But generally what we’re talking about is stuff that you purchase regularly, which means a lot of replenishment. Now that’s very different than buying a lawnmower. Because these businesses, as I’m going to talk about, are a lot about sort of brand equity, the relationship with the consumer. It is very hard to have any of that happen if people only buy your product once every two years. So you’ve got to have sort of a frequency of purchase or engagement or usage to do any of this. So that’s kind of the defining characteristic. This is stuff you purchase regularly. Usually these things are also low price. We’re not talking about a hundred bucks, we’re talking about $4, $6, things like that. There is usually, at least traditionally, within this category, a big aspect is sort of the fight for shelf space, that these things are universally available. There’s very wide distribution of something you buy pretty regularly at a fairly low price. That’s kind of the category, and then FMCG is just much faster. That stuff where like, you know, you buy cokes and beers every day. So these are the, you know, the trucks you see going up and down the street all day long. You’re not going to see big trucks with mustard and flour going up and down the street, but you stand in front of a seven 11. You’re going to see the coke truck pull up all the time. That’s FMCG. Now, within all these, they can be commodities. They can be highly differentiated and branded Coca-Cola, but be one monster energy is another, but they can be commodities as well. Okay, so there’s your general traditional category for this. And a lot of investors like Buffett and Russo have talked about legacy brands, where these are brands that you’ve heard of your whole life, like Heinz Ketchup, Coca-Cola, where they’ve got this 30, 40, 50 year history, so there’s this pervasive awareness of them in the population, and then you buy them regularly. So that could be a subcategory of legacy brands. Okay. Given that, let’s just jump to one of the strongest versions. Now within all of this, most of these don’t have real competitive strength. They just don’t. I mean, it’s a game of scale. You’re trying to get on the shelf space. You’re trying to get a good location, but customers don’t pay too much attention to one type of flower versus another. So for most of these brands, it’s just an operational fight. Even if you do lots of marketing, Customers just don’t care. You can’t put up billboards all over town about this type of flower versus another type people Just don’t care that much But some like coca-cola Red Bull you can Doritos things like that Okay, so let’s talk about a particularly strong case in my opinion, which is Monster Energy publicly traded MNST is the the ticker And I wrote about them in terms of share of the consumer mind which is the first concept for today, that’s on my list of competitive advantages. That’s not my phrase, that’s an old Warren Buffett phrase. And basically, it’s a type of customer capture where like, everyone talks about having a brand. Like that’s something special. It’s not a brand is just an asset. It’s no different than having a store, which is an asset or a factory. That’s an asset. It’s just an intangible asset. Anyone can have a brand. You just put up billboards all over town, you’re a brand. So it’s not the brand that is the source of competitive power, it’s the presence in people’s minds that you have created, the share of their mind, that’s the competitive advantage. So share of the consumer mind is a good way to think about it. So here’s what I wrote two plus years ago, competitive advantages on the demand side, sometimes called revenue advantages. These are structural advantages that enable premium pricing, repeat purchases, higher ROIC, and or stable market share over longer periods of time. That was sort of my definition for this. That’s actually pretty specific language. How do I know if a company has real competitive power, a competitive advantage on the demand side, share of the consumer? I’ve got to see one of these things. I’ve got to see the ability to premium price, 10%. This ketchup Heinz is 10% more than Jeff Ketchup and people will pay it. That would be some degree of proof that they’ve got some competitive power. Repeat purchases, even if you’re at the same price, you’re not premium price, if people are always walking down the aisle and they’re always picking up Heinz, that would be another example of that. Softer, but still. higher return on invested capital that would play out from the pricing and or stable market share You know if one company’s got 20 25 percent of the catch-up market year after year after year That’s usually evidence of some degree of defensibility and you want to see all of these things over some degree of time like five years Ten years not you had a good course You see that you start to think, okay, there’s something going on here. They’ve got some presence in people’s minds. Now, one of the reasons I love share of the consumer mind is a competitive advantage, is because this is one of those ones where digital is just exploding the category. I mean, there’s so many interesting things going on with data in software. that play out in people’s brains. It used to be like share of the consumer mind was, you are the ketchup that everybody knew. Because you’ve been putting billboards up all over town for 20 years and you’re on the NBC and there’s only three TV stations. Right, it was just brute force advertising, very unsubtle. Well, software is really good at teasing out the peculiarities of your mind and building itself in there. So… Digital meets share of the consumer mind is like one of the most exciting places to focus on. It’s on my short list of like two or three of the most important things to look at. Okay, um, finish up this quote. The power is in their capture of the consumer mind. That’s the real intangible value. And this can be done by emotional impact. It can be done by the creation of habits. It can be done by chemical addiction. there’s lots of mechanisms by which you can sort of hack the human brain. And it’s getting more and more sophisticated and complicated as we go. So, within all of that, and I have lists of these I check for, but within all of that, caffeine and sugar is just a standard, how are you going after the consumer mind? Well, we’re using two tactics, two mechanisms. We are pushing caffeine and sugar, which is highly addictive, and we’ll just jam as much of that in a can as we can. And we’ll also do habit formation, which is a whole process in the brain where if you get people to do something every day, it will basically get hardwired into the brain that that’s what they do. You become a daily habit. Both of those things are fairly powerful, and Coca-Cola has them. Red Bull took it to the next level by basically just, you know, your average can of Coke has like 20 milligrams of caffeine. I don’t remember up top, I had 20 milligrams of caffeine, something like 30 grams of sugar. You know, Red Bull took that up to 75 milligrams of caffeine. Well, Monster took it up to 150. Some of their cans have 225 milligrams of caffeine. I mean, those cans are huge. So they just sort of pushed that, you know, up and. I think that’s always a good business model. Actually, I looked it up. Here it is, I have the exact numbers. Monster Energy, which is a 16 fluid ounce can, 160 milligrams of caffeine, 54 grams of sugar. Now compare that to Red Bull, 80 milligrams of caffeine, 27 grams of sugar. I was pretty close on that one, actually. Coca-Cola, 32 milligrams of caffeine, 39 grams of sugar. So Monster basically doubled the caffeine and pretty much the sugar. Now, if you look at Starbucks, they’re all kind of, most drinks, like even the most caffeinated stuff at Starbucks, which is usually like the Americano, it’s the drip coffee, it’s not the lattes. Lattes are like 75 milligrams of caffeine, but like those big sort of Americanos, that’s 150 milligrams. You rarely see anything with more than 200. and then at around 300 milligrams of caffeine, that’s when doctors start saying, hey, that’s too much caffeine in a day. Five hour energy, which is those little shots, that’s 200 milligrams of caffeine. Oh, here’s Starbucks brewed coffee, a tall, which is their smaller size, 230 milligrams of caffeine. But no sugar, which is actually better for you. OK, so we jump to Monster Energy. They sell 50 plus types of drinks. For those of you who haven’t seen them, I mean these are these brightly colored huge cans. You can’t miss them. You can see them from halfway across the store, which is a big part of their marketing. It’s a visual. Very distinctive. Now they have other energy drink brands, which are, one of them’s called Predator, which is a good name for an energy drink. One of them’s called NOS, which I think is like nitrous oxide maybe. Then they do a little coffee and water, but generally they’re big. You know, their big gun is the Monster brand. And they sell these to bottlers and full-servage beverage distributors. So they’re not doing the bottling. They are not doing the distribution. They’re not doing, they are in the syrup and marketing business. They make a lot of syrup, which you can do very cheaply. And then they have a ton of people doing marketing. And then it goes out to distributors and bottlers and people who do all that other stuff, which is much more capital intensive. The economics are not as good. And that’s… It’s pretty much how Coca-Cola works as well. You know, there’s a split between their core business, which is basically the same, and then all their bottlers and distributors worldwide. Okay, so then you walk around the United States and you will see Monster everywhere. Grocery stores, wholesalers, club stores, convenience stores, drug stores, merchandise, special, they’re everywhere. And so they’re very good at getting shelf space, and then… getting good placement within those stores. Gas stations, you’ll see it all over the place. Okay, that’s basically the business. There’s not a lot going on on the supply side either. The raw materials are like aluminum, PET bottles, some packaging, glucose, syrup, sugar, milk, caffeine, but there’s really not much going on. It’s pretty much taking a bunch of widely available commodities. turning it into a syrup, doing a ton of marketing, and then selling it for two to three bucks a can. Very good economics, pretty capital light. So here’s some of their numbers. This is 2018. Net sales in 2018 was about $4 billion, $3.8 billion. Most of that’s in the US. Within that $3.8 billion of net sales, the gross profit was 60%. That’s a really good product. I guarantee you the people that make flour aren’t making 60% gross profit. And then the operating cash flow, 1.6 billion. So the operating income’s about 33% of the net sales. That’s a really attractive operating margin for a capital light business. I mean, if you look at the balance sheet, there’s nothing there. I mean, there’s just nothing there. There’s no tangible assets. There’s some working capital because they have accounts receivable and inventory, but apart from that, I mean, there’s not a lot there. So it’s a really kind of simple business. I mean, there’s just not a lot going on operationally. So that sort of raises a really good question, which is, how does such a simple business have such tremendous economics and have competitive power such that they’re not getting beat. How is that possible? I mean, companies with massive numbers of engineers are fighting for small margins against tons of competitors. Meanwhile, the syrup and marketing company is just rocking and rolling, right? So I like these sort of simple businesses where they’ve clearly tapped into something powerful such that they can have these sorts of returns. And it ain’t operational complexity and it ain’t engineering. and an eight rapid innovation, it’s none of that. I mean, they’ve got some very basic competitive advantages that are just playing out. Now, if you look at their 10K, which is a really good read, by the way, I mean, they talk about their standard factors that they worry about in their competition, and they talk about pricing and packaging, and hey, we’ve got some new flavors, and we do a lot of marketing and distribution, and it’s pretty simple. I think, and here’s the so what. This is really just a couple things. And this is a good example of share of the consumer, a very effective CPG company in a pre-digital world. And then we’ll compare it with post-digital in a minute. So pre-digital, what do we got? We’ve got a very popular product with captured consumers. Basically, this is share of the consumer mind. mostly by chemistry, sugar and caffeine. And also there’s some other things going on as well. It’s not purely that. It’s also about the fact that there is a degree of habit formation when people, people who get this stuff, they go every day. You know, most people who get drink caffeine like me, it’s an everyday thing. So there’s habit formation. And then on top of that, there is the fact that it does taste really good. I mean, so there’s a bit of happiness. and emotional satisfaction going on, but the typical customer is going to have two, three, four servings per week. And I think it’s about 50% chemical and habit formation and then maybe a bit of emotional and that all sort of gets reinforced when you make it as convenient as possible. You put it everywhere, you see it everywhere so that you know you can have sort of impulse purchases that reinforces all of this. and that business model is pretty much the Red Bull and the Coca-Cola business model as well. That’s kind of the main thing. Second to that, they’ve got differentiated marketing, which for them is overwhelmingly visual. Big, brightly colored cans. You’re not gonna see a ton of ads. You know, Red Bull does a lot of these videos with extreme sports and stuff. They don’t do that as much, but they’ve got good marketing. And then the third bit is sort of universal distribution. And you’ve got to have some degree of leverage and negotiating power with the major retailers. Getting the shelf space, you’re not going to get that unless you have a really popular product. So you kind of need the first to get the second. But you know, power with the retailers, that’s a big deal as well. Okay, so Monster Energy mostly focuses on those first two and they… do the sort of relationship with retailers and such with the partnership with Coca-Cola, which own last time I checked, they own a 19% stake in Monster. So, and Coca-Cola can’t compete with Monster in energy drinks. So when I was reading this years ago, I was like, this is a great business model. I mean, you’ve got the product, you’ve got great shelves space, and then you got the partnership with Coke for distribution. I mean, that’s pretty spectacular. So anyways. And if you look at their head count, about 3,100 employees, this is 2018, a little out of date, about 2,300 of them are full-time, but of the 3,100 total employees, 2,200 of them are doing marketing. So this is overwhelmingly a marketing company. Anyways, if we put that in sort of my language of competitive advantage, and I’ll finish this part up right now, what’s going on? Well, we look at my sort of six levels. barriers to entry, competitive advantages, digital marathons, what do we got going on? As I’ve kind of said, look, it’s mostly share of the consumer mind. And then second to that, we have economy, historically, we have his economies of scale in marketing, right? If you’ve got a big product selling 3 billion a year and you’re spending 15 to 20% of your sales on marketing, you’re going to outspend any smaller rival in energy drink. And those two things reinforce each other. You know, as you spend more and more and more versus your rivals, you’re going to have a greater presence in people’s minds. So your share of the consumer mind increases. That makes you bigger. That gets you more economies of scale and marketing. There’s a nice sort of flywheel between economies of scale and marketing and share of the consumer mind. And then second to that, they have some economies of scale and logistics and distribution, but that’s via Coca-Cola. That would be a very standard explanation for a very effective CPG company. That sort of strategic picture for Monster. Okay, now let’s get sort of the other point of today’s talk, which is, how is digital changing all of that? Because it’s actually got some pretty sweeping changes for all CPG companies, including Monster. So that’ll be sort of the next. Now, against the picture I just sort of described, the standard digital argument goes something like this. These traditional CPG giants, of which there are a lot of them, Nestle, Procter & Gain, pretty much everything in a supermarket, right? They are facing more and more problems. Number one, well, people are buying online. E-commerce. Well, a lot of their game plan, for most companies, have nothing like the power of Monster Energy. If you’re flour, water, basic Tylenol type products. I mean… For most of them, their playbook was to get shelf space and then to be very visual and do promotions in stores. Well, e-commerce shifts all of that online and suddenly they’re not competing against, let’s say, five or 10 different brands of, let’s say, aspirin in the drugstore. They’re competing with hundreds. So the shift from retail, physical retail, onto e-commerce has been a real challenge for most brands. retailers, especially in the United States, have been consolidating. Walmart gets stronger and stronger. So they have more and more negotiating leverage against most brands. Now the brands have also sort of consolidated under groups like Procter and Gamble and Nestle. So they’ve also sort of grouped up, but that’s been going on. And then like probably one of the biggest ones is the fact that like their game used to be get shelf space and then outspend everybody on marketing for your category economies of scale. Well, that worked real well in the era of mass markets where everyone was using Heinz ketchup. But, and how do you market? Well, you buy TV spots and you buy billboards. Well, now you can go online and you can go after micro markets. So the mass markets have been fragmenting. and lots of smaller niche brands have been popping up who are very good at micro marketing, micro targeting. And so you see the market share of these major mass market products, let’s say Ketchup or Aspen, they’ve been shrinking slowly as smaller brands keep popping up and they find they don’t need to compete with the ad spend of these major companies. They can just be really clever on social media and go after a very specific demographic. So we see all these micro, and that’s really just the fragmentation. We’re no longer in a one size fits all consumer world. Now, you know, if you want a special type of coffee that comes in a little shot glass and you drink it right before you go to the gym and it boosts you up and then you work out harder, well, there’s a coffee for that now. Right, there’s all these tons of, so we see these micro brands eating away at these large players who have been relying on scale advantages. That’s the standard story. And now against that story, a company like Monster was actually in very good shape because that is very disruptive to say, someone who is selling, I don’t know, aspirin. Because you don’t need it necessarily right now. Well, maybe if you have a headache, but let’s say just standard products you’re buying all the time like ketchup. You can buy it online, you can wait five days, you can try new brands, blah, blah, blah. Okay, Monster and a lot of FMCG has sort of been the most resistant to this trend because these are the things that, you know, they’re impulse purchases. They’re fast moving, they’re convenient. I don’t wanna wait two days to get my Coca-Cola. I’m gonna walk over, there’s the, you know, I can see it right there at the 7-Eleven, I’m gonna go buy it. So a lot of groceries and FMCG were probably the most resistant to this phenomenon, even though in China in particular we see that going away more than anywhere else. Okay, so Monster was protected there, but again, beyond that sort of standard assessment of what’s going on, Benedict Evans, who is a, he’s sort of a media analyst in the United States. You’ll see him online all the time. He’s pretty well known. He released his four tech trends, or his tech trends for 2023 a couple weeks ago. And I went through it. Those of you who are in our line group, I sent you a couple of the slides from his presentation. I thought it was fine. I don’t usually agree with him on too much, but he did have one slide that got my attention and I’m gonna put this in the show notes. He basically argued that the brand CPG in particular, well I’m saying CPG in particular, is becoming unbundled. That the advantages of scale that most of these companies have been built on are now in question. And there’s four categories of this. I’ll put the slide in the show notes. The first one is the one I just said, that look, we’re seeing lots of newer segments emerge, micro brands, we’re seeing smaller demographics, we’re seeing specific targeting. So having a scale advantage in marketing spend is not as strong as it used to be. So that would be an unbundling of the process such that the advantages of scale are in question. The second one he lists was social video and streaming. It used to be if you were a CPG company, the way you engaged with your customer was when they walked into the store and you were in the gas station in the little cooler next to the cashier. Well, there’s lots of ways for these brands to now engage with their user customers beyond stores, social media, video streaming influencers. They have a lot of ability to do that. And Now I don’t necessarily want to watch a lot of videos about flower, but it is surprising how creative some of these brands are. They take some regular product you’ve never thought of and they start putting content out about this is a special type of mustard from the south of France and it’s made by these mustard seeds which you’ve never heard. And Vincent van Gogh used to love these when he lived in… I mean I’m making that up. But they can start to tell a story. about their brand that is far richer than I have a bright label and I’m on the shelf at eye level. That’s used to be how they established their brand was let’s have a bright color, we’ll put it on the shelf, maybe we’ll put a cartoon character on it, but that was their brand story. Well now they can tell really interesting ones. So social video and streaming, that’s another area where it may not be about outspending people and getting better shelf space. it could be about who’s more creative and who has a compelling story and who’s better at video and social and streaming. So that’s sort of number two. Number three, new channels, new logistics. The new channels everyone talks about, omni-channel. But you also want to think about logistics. FMCG and CPG are doing lots of interesting experiments in China with companies like JD Logistics. where JD Logistics is starting to move around their products, their inventory levels in local communities in almost real time. So there’s actually some logistics channels there that are interesting and then there’s sort of omni-channel stuff. Last one, outsourced production runs and short runs. Now Monster already does this, they just make the syrup and then they do the marketing. So they’ve already outsourced their bottling and their production. But there’s also this idea that like, not only can you just outsource, like I could start my own energy drink tomorrow, sitting in a garage and just outsourcing everything, but I could even outsource the syrup manufacturing. Almost everything but the marketing. But there’s this idea of short runs where you’re not making one brand that lasts for 20 years. You’re doing rapid brands. You have a… let’s say it’s carnival this week in Brazil, we have a carnival energy drink, and it’s only this week. And then we have a New Year’s energy drink. And suddenly you’re doing these short runs, limited, collectible, whatever, and it becomes much more dynamic than we have the same formula for Coca-Cola for the last 50 years. So those four things, new segments, smaller demos, targeting, social video streaming, new channels, new logistics, outsourced productions, All of those hit to the center of the competitive advantages I just mentioned for Monster. And I think they’re fairly well insulated from most of that. But most brands have nothing like the power they do. CBG brands, FMCG is in better shape because of the nature of fast movie. But all of those are an interesting. And I thought that was a very sort of interesting point that he made. So I started to think, okay, what would be my answer to that? Because CBG companies are a client. And I really sort of came down to the pretty simple answer to this, which was, if you go through my six levels, I am always interested at what point does an operating activity become a competitive strength? If you’re operating, typical company, manufacturing, distribution. And if you’re doing the digital operating basics, which are level five of mine, all of that stuff is important. None of those create structural advantages. At what point does an operating activity rise to the level of others can’t do what I do as well? And I call, basically this one plays out in two places. The first would be, well, let me just talk about one. The first would be ecosystem participation. And that was the other concept for today. Share of the consumer in mind goes digital and ecosystem participation. If you look on my six levels, level four is digital marathon. These are five types of digital activities that I think you can start to pull away from your competitors. And at a certain point, it becomes an advantage. And the acronym I use is SMILE, S-M-I-L-E. The E stands for ecosystem orchestration or participation. Basically, you are participating in an ecosystem that you don’t control as a CPG brand, but you are so good at it, and you are so much better than everyone else that you really start to leave them in the dust. It’s a marathon. You get better and better and better at this. Now, what would be an ecosystem? Well, an ecosystem could be, you’re on Amazon. Yes, and that’s pretty much everyone is selling on Amazon in the US. If you look at a company like Nike, very powerful. They have their own apps. They have their own physical stores. They still are selling 50 to 60% of all their goods through Amazon. So even the most powerful brands are still participating in this ecosystem, i.e. platform controlled by Amazon. And in China, you have to be on Taobao. You just have to. If you’re in Southeast Asia, you gotta be on Shopee and Lazada. So this idea that you’re gonna have to say, look, your core skills are no longer making syrup and doing marketing. Your core skills are syrup, marketing, and ecosystem participation. And that third one is probably the only one where you can pull so far ahead of your competitors, they can’t catch you. And an example of that I’ve pointed to in the past is Perfect Diary. which was a Chinese makeup brand. They’ve sorted their public, you can look them up. They came out of nowhere as a makeup company. And L’Oreal has long been the number one makeup brand of China. Perfect Diary comes out of nowhere, and within about 18 months, they dethrone L’Oreal as the most popular makeup brand in China. And what they did, and they were… Their only thing, their makeup was pretty basic. They were very small, but they were unbelievably good at ecosystem participation. They built a huge network of influencers. They were on Taobao, and they basically built a whole system around working with the ecosystems. So they were on Taobao and JD selling that way, but they were also working on Weibo and WeChat, working with influencers. So they were participating in two environments they didn’t control. but they were so good at it that they rocketed up to number one within about 18 months with their first brand which was called Perfect Diary, that was the makeup brand. Now since then L’Oreal responded and has regained but that kind of phenomenon is really interesting and I think that was their primary skill. They were unbelievably good at ecosystem participation. So that’s one, the other ones you could kind of take a look at. are Shien and Tmoo. Shien is obviously the direct to consumer, ultra fast retailer that has come out of nowhere in the last couple of years and moved to number one, number two, number three, in terms of e-commerce in the United States, but really everywhere. If you go to Brazil, everyone talks about Shien. You go to Mexico, everyone talks about Shien. They are everywhere. Now they’re a retailer, so it’s a bit different, Really all they were good at, shouldn’t say all, what they were especially good at was basically digital marketing and working with YouTube and working with Pinterest and working with Amazon. And now they’ve since built their own direct app and webpage, which most companies can’t do. But I would put them in the same thing. That’s how they shocked Zara and H&M, who were the giants in terms of fast fashion. this company came out of nowhere and shocked them. And I would argue it’s the same type of phenomenon as Perfect Diary. And the latest version of this is Tmoo, which is pin duo duo China. They launched basically a copy of Xi’an. They launched in October. I think they’re still number one. I mean, they have absolutely rocketed up in the United States on app downloads. And they’ve been number one or in the top three for a couple months. And they just came out of nowhere in October. Same play, they’re just really good at digital marketing and participating in these ecosystems. Now they have their own app, so it’s a little more complicated, but basically the idea’s the same. So let me get to the so what for today. So here’s the so what. The traditional playbook for winning as a CPG brand, I think Monster is a great example of that. And most companies have a… A few companies have as strong a picture as Monster. Most are weaker and are somewhere in the middle. Okay, against that scenario, the world is going digital. Lots of changes, lots of going on. Some companies are getting impacted more than others. I think Monster’s getting impacted less. The playbook to win as CPG increasingly goes digital, in my opinion, the way you win, and this is what I would tell clients. The biggest lever in this game is share of the consumer mind by digital. You’ve got to be incredibly good at using software, data, AI, predictive analytics, all of that to hack the human mind. The same way Monster does it with caffeine, a little bit of habit formation and some other things. That is 75% of the game going forward. You’ve got to figure out how to play that, because that is really the biggest, and it may turn out one day to be the only source of advantage. People love my product. That’s all that matters. So number one, share of the consumer mind by digital tools. The only other lever I can see going forward is ecosystem participation. I would have an entire team. I’d have the vast majority of the management team and all the staff saying, Our job is to be the most effective brand, let’s say in ketchup, on Amazon. You know, we’ve got social media, we’ve got streaming, we’ve got a huge brand story, we are a great participant, and every time Amazon changes the rules, we are adapting to the new rules faster than anyone else because we know everything. Right, those would be the two skills I would point to. Like, if you’re gonna win in this game as a C-cheap, B-cheap brand going forward, those are the two skills that matter. share of the consumer mind in digital, and then ecosystem participation. Then there’s a lot of other stuff that’s necessary, but those are the only two big guns I can see. And that would be sort of my basic playbook for winning over one, two, three, four years. Okay, I think that’s enough of that for today. It’s a pretty cool, it’s a really cool subject. Like, when I look at sort of where, because I mean, I study where does digital meet competitive advantage and competitive strength. And a lot of it’s pretty basic, but there’s a couple areas that are just exploding, and one of them is share of the consumer mind. Switching costs are also pretty interesting. Machine learning, there’s a couple things that are really interesting you can dig into, and a lot of it, besides that, is kind of basic. So this is on my short list of areas to keep an eye on. Okay, I think that is it for today in terms of content. The two concepts, share of the consumer mind, ecosystem participation. Take a look at Monster Energy. It’s a pretty cool company. Try their drinks. I mean, it’s a huge jolt of sugar and caffeine. But it’s pretty good. Yeah, and that is the content for today. As for me, it’s just been a nice quiet week working. Yeah, not much going on. For those of you who are subscribers, I sent you three articles about sort of small Warren Buffett companies. I’ve sort of shifted a little back, instead of going into these Amazons and these Microsoft, which are really complicated digital creatures, I’ve been sort of going back to simpler companies in the last week or so, soda, energy drinks, furniture, jewelry. So anyways, I sent three decently long articles of just the competitive advantages of like furniture and jewelry and buying party favors. So it’s… That was actually kind of fun. I’ve sort of enjoyed getting out of all the complexity for a little bit. I’ll probably jump back into it shortly. But yeah, that’s kind of what I’ve been doing this week. Not much else going on. What else? I saw Ant-Man. I’m like a huge Marvel fan, because I’ve read those comic books when I was a little kid. So the fact that they make all these movies has been spectacular for me. But… Boy, they really have kind of stunk the last two years. Like all of them are like, not all, pretty much. Like it’s just one mediocre one after the next. It’s, I’m losing faith a little bit, but it was fine. Like if you want to go see a movie, go see Ant-Man, it was, if you go in with the expectation that, hey, this isn’t going to be awesome, but it’s, it’ll be fun to watch, then it would be pretty good. Which was kind of my expectation. Cause I read it wasn’t, it was, you know, pretty mediocre, but, eh. Not bad, I suppose. It’s not a bad way to spend a couple hours. So, yeah, isn’t that ridiculous? They spent, what, $200 million on that movie, and here I am like, eh, I don’t really like it that much. Like, it’s still a pretty good deal for 10 bucks to go see something that costs them $200 million to make. So I guess I shouldn’t complain. Anyways, that’s it for me. I hope everyone is doing well. If there’s any companies you want maybe me to take a look at, I’m gonna start. getting back into the digital companies probably this week. But if you have any suggestions, let me know. I’m always interested in finding out new companies. Anyways, that’s it for me. I hope everyone’s well. Talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.