This week’s podcast is about Microsoft and how I approach its valuation.

You can listen to this podcast here, which has the slides and graphics mentioned. Also available at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is the link to the Asia Tech Tour.

———-

Related articles:

- An Intro to Growth and “Birds in the Bush” in Digital Valuation (Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- An Intro to Discount Rates and Cost of Capital for Digital Valuation (Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Why DCF Sucks for Digital Valuation. (Tech Strategy – Podcast 101)

- An Intro to Digital Valuation (Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Valuation Like Warren Buffett in 1 Slide (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Valuation (Question 3): Digital Valuation

- Valuation: Bird in Hand vs. Bush

- Valuation: Growth, ROIC/RONIC and Value

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Microsoft

Photo by Ed Hardie on Unsplash

———-Transcription Below

:

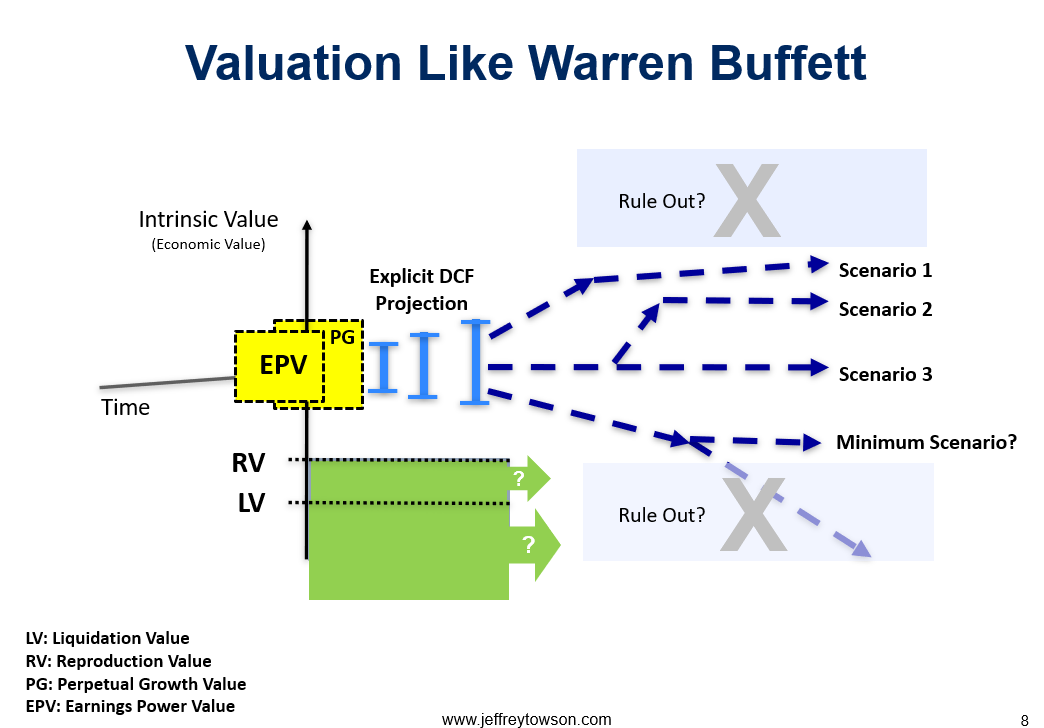

Welcome welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the tech strategy podcast where we analyze and value the best digital businesses of the US China and Asia and the topic for today my valuation for Microsoft So this is a bit of I guess not a pivot but altering the content Let’s say 30% of this podcast and the subscription newsletter, which is I’m gonna start doing something I haven’t been doing in two plus years which is I’m gonna talk about valuation for these companies and put numbers on it, you know, for Microsoft today, but going forward. And you know, that is a bit of a change because I’ve been focusing on assessing the quality of the companies, the business models, the strategy, but haven’t really said, okay, and based on this, I think this company is worth so much. Well, I’m gonna start doing that now, going forward and Microsoft will be the first one. So a bit of a change there, hopefully that’ll make it. more valuable, because I haven’t really talked about that, and I probably should have. I’m honestly, I’m much stronger on the strategy stuff. I’m much stronger, in my opinion, on assessing business models and competition and what factors and variables matter, as opposed to putting a number on a particular company. So I’m gonna put more of ranges. But yeah, we’ll start doing that today. Okay, and Microsoft will be the first one. For those of you who are subscribers, I’ve sent you two articles on Microsoft in the last week sort of taking apart the business model. I don’t think it’s awesome. I think it’s solid. I think it’s a decent framework for thinking about this business. But one of the reasons I’m really interested in Microsoft is in terms of strong business models, it is at the top of the list. This thing is one of the most powerful business models out there. It seems to be getting stronger. So I sort of broke down how I take it apart in a two part series that went out in the last couple days. I think that’s probably most of what I’ll talk about for Microsoft. So anyways, I thought valuation, I’ll talk a little bit about that today, but I thought this was a good one to talk about valuation. The other thing is with the group here in Bangkok, hi everyone from Bangkok, we’ve started doing valuations of these companies in the last couple, in the last month or so. putting teams together, we’ve been working on Microsoft. So a lot of this thinking is not mine, it’s other people as well. I’ll give you my take on it, but I don’t wanna take credit for other people’s work. And then the next one we’re ramping up right now will be Amazon. So that’ll be kind of the next company to put a number on in the next couple weeks probably. Anyways, that’s where we are. If there’s anyone out there who wants to be part of this, let’s call it the valuation group, send me a quick note. Send it on LinkedIn is probably the easiest way to do it. And we’ll start doing that more online as opposed to in person, which is what we’ve been doing. So if you’re interested in the valuation side, send me a quick note and we’ll start to get you into those chat discussions. Let’s see, for those of you who aren’t subscribers, feel free to go over to jeffthousen.com. You can sign up there, free 30-day trial, see what you think. Other stuff coming up, as mentioned, Asia Tech Tour. is set for March, maybe April as well. We’re gonna do a five day tour, Jakarta, Singapore, Thailand, visit some companies and really do sort of an intensive training in digital thinking. So it’s gonna be a lot of lecturing, me, some guest lecturers, company visits, and then, you know, just fun. Cause this is a really fun part of the world. So if you’re interested in that, send me a quick note. You can email me at info at thousandgroup.com or go over to thousandgroup.com, the website, and just look at the Asia Tech Tour. All the information is there now. And that’s what’s coming up. And okay, with that, I think that’s enough of housekeeping. Let’s, oh, standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guess may be incorrect. If you use an Express. may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment legal or tax advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the valuation. Now, sort of standard Warren Buffett lore 101 is, he’s often asked like, if you were gonna teach at business school, which I do, what would you teach? And he always says, I would teach two courses. I would teach one course for how to analyze a business, and then I’d teach one course on how to value a business. Which is pretty much what I’ve been copying for six, seven years, something like that. Everything I’ve been talking about here. is about assessing the quality of a business, figuring out who’s gonna win, and then my niche is obviously digital. But I’ve also been teaching valuation. How do you put numbers on these? And Buffett is very sort of open about the first one. He talks about what he looks for in a business. He’s pretty coy about how he values businesses. He really does not talk about how he does it. I’ve actually asked him sitting down at a lunch, like, if you were going to, I mean, this is literally one of my questions was, if you were going to teach a valuation course, how would you teach it? By the way, I teach evaluation course, right? That’s kind of what I said. And his answer was a bit coy, but it was basically that he would, he referred to sort of ASAP’s fables where he said, I would teach it based on, you know, a bird in the hand versus a bird in the bush. which is sort of an old saying, a bird in the hand is worth more than a bird in the bush or whatever it is, which is not a really helpful phrase because nobody really hunts birds anymore, so it’s not super helpful in that sense. He’s had a variation on this where he says a girl in the convertible is worth two in the phone book. Okay, that one’s not awesome either. What he’s talking about in my opinion, which is the framework I’m gonna use today. for Microsoft is you have to sort of look at the value of the business and then assess how predictable is it. And certain types of value, certain areas of value in a business are very predictable because you can see them today. They’re real, you can project them forward. Other sources of value are emerging. That’s the bird in the bush. And he kind of went on about this at lunch. He said, you know, I would look at the bird in the hand, and then I would look at the bird in the bush, and I would ask myself, how much is the bird in the bush, and when is it going to arrive? And you’ll see I basically use that exact same framework for thinking about Microsoft. Here’s the value we can see today, and it’s predictable. Here’s the sources of value in the future that maybe people aren’t looking at. It’s less predictable, but we wanna sort of get our brains around the value. sort of bird in the hand and the value bird in the bush. And here’s when I think it’s gonna arrive. So you’ll see that’s the framework I use. And I’ve spent a huge amount of time, like, I don’t know, six, seven years reverse engineering what I think Buffett and probably seven or eight other investors do to assess the quality of the company. I’ve also done sort of the same exercise for valuation. I have pretty specific frameworks that are all reverse engineered. Buffett is sort of my go-to guy, but he’s the most vague on this question. So anyway, that’s gonna lay out here today. I’ll point you to some articles if you wanna know. The three concepts, well let’s say two concepts for today in the concept library on the webpage. What we’ll call valuation, digital valuation. How do you value a digital company, which is different. And then the other concept is valuation with bird in the hand versus bird in the bush. Those are the two concepts for today. They’re both in the concept library. Anyways, there’s actually kind of a lot on valuation in the library. About a year ago, I did quite a large number of articles on this subject. Most of those are only for subscribers, but you can go there and look and you’ll see them. Okay, so let’s do this in three steps. Step one, talk about the quality of the company. Step two, a full sort of valuation approach. Step three, back of the napkin valuation, bird in the hand versus bird in the bush. Now, for the first one… If you go to my website, I published an article a couple days ago called Microsoft’s Azure Strategy is two platforms plus infrastructure. That’s basically my assessment of what they’re doing at Microsoft. Two platforms plus infrastructure, that’s it. And if you actually break down, one of the problems with digital businesses is… Usually when you value a company, you start looking at business lines, you start looking at revenue streams, and then you try and project those forward. And that’s very easy to do when you’re talking about Coca-Cola, because the business line is we sell cans of Coke, everything we sell is a transaction. There’s the revenue from Coke, there’s the revenue from Diet Coke, and so on. But once you move into digital businesses, particularly platform business models, which is all Microsoft builds, pretty much. you realize you’re really building platforms, you’re building ecosystems, and you’re generating lots of user engagement. And then from that user engagement, lots of little revenue streams emerge. So it’s harder to break it down by a series of revenue streams and project those forward, like we sell Coke, we sell Diet Coke, we sell Fanta, because the revenue comes from lots of little places. So you really have to start by projecting, not the revenue streams forward, but projecting the users, the engagement, and the platforms forward. And then the revenue comes out of that in lots of little places. So you kinda gotta do the strategy first, and the operating model first, and the engagement and the users first, before you can jump to here’s my six business lines. Now if you look at, the revenue for Microsoft, you’ll see it comes from about seven places, which is an example of that. They will break it out in their 10Ks. They’ll talk about server products and cloud services. Okay, that’s Azure. That’s selling basic enterprise stuff. And that’s about 30 to 40% of their revenue, 2022. then we can go to Office products and cloud services. So that’s their productivity software. That is increasingly things like Teams, communication software, Skype. That’s about 22% of their revenue. And those numbers have been shifting significantly. They’re moving on to cloud, becoming less about Office products, Microsoft Word, Windows. I’m sorry, Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, Excel. Number three in terms of revenue, 12% is Windows. Again, that’s overwhelmingly personal computers, not cloud, historically. Number four is gaming, Xbox, 8%. LinkedIn, 8%. Search advertising, Bing, things like that, 6%. So you keep going down, you get into devices and other stuff. But you look at, you’ve got like at least seven major sources of revenue and it’s pretty scattered. And that’s, when you see a picture like that, it’s a big red flag that you can’t value this thing like a Coca-Cola. A traditional physical business. You have to start looking at it like a platform business model and project those forward with the idea that the revenue will scale along the way. So that’s kind of the first thing. So that’s sort of like, okay, Step number one for taking apart Microsoft, you have to stop thinking in terms of those business lines. And you need to think about two platform business models plus infrastructure. That’s my take on this. What are the two platforms? The first platform is an innovation platform. The second platform is a coordination, collaboration, and standardization platform, a CCS platform. I’ve talked about these as two of the five types of platform business models. It’s in the concept library. There’s literally 50 articles and podcasts on this. But they have two complimentary platform business models that they’ve been building since 1990. The innovation platform, which is where the two user groups are going to be the users of the computer system and developers of the computer system, well that’s Windows, right? It’s an operating system. That’s an innovation platform. People are building various things on this platform. In this case, it’s software. There’s a lot of software that runs on Windows. Okay, you could say the App Store is the same. Some people call the App Store more of a marketplace. You could consider Android an innovation platform. You can consider iOS on your smartphone a platform. Well, historically, they’ve run the operating system, the innovation platform on personal computers and to some degree on enterprise. Okay, as they shift from those platform types, those computing paradigms to the cloud, They are also building a massive innovation platform on the cloud, which is sort of the cloud equivalent of Windows. What are they doing? Well, they’re helping developers build on this. They’ve purchased GitHub, which is about 80 million plus developers right on GitHub. A lot of companies, enterprise. They’re doing Power Platform, which is basically creating lots of tools that enable anyone to do no code and low code developer. If you wanna be a developer, it used to be you had to learn to write, you know, JavaScript, HTML, you know, all of this is a very advanced skill. Well, one of the, you know, one of the big things Microsoft has been doing in the last year is Power Platform. It’s something that Sachin Adela talks a lot about that this is the future, which is no code development. or low code development, where your typical company can start to create apps and software without having to know how to code. Microsoft will give you the tools. Now that is the equivalent of TikTok. What TikTok did very powerfully was if you wanted to be a content creator, you had to buy cameras and set up a little YouTube studio in your house, and it was a bit of work, and learn how to edit, and that’s Photoshop, and Adobe, and Light, you know, a lot of skills. They basically democratized that by saying, look, anyone with a smartphone can now become a content creator. Just turn the phone around, start filming, videoing. will give you lots of little tools on TikTok where you can add filters and music and all of this, and you can become a content creator. That’s what TikTok did. That’s what YouTube is increasingly doing. You could argue that’s what Epic Games is doing with their Unreal Engine. They are democratizing content creation that anyone can do it. Pretty much anyone’s gonna be able to make a TV show or a movie soon. You can just use the Unreal Engine at Epic and anyone can make a TV show at the same quality as Game of Thrones. That’s what’s coming in a couple of years. The same way TikTok made it possible for anyone with a smartphone to become a content creator. Well, Microsoft is doing the same thing with developing software and apps. Anyone is gonna be able to do it. even if you don’t know how to code. If you have a small business with a lot of data, you can just go into their product suite, Power Platform, and start to write apps. And then you can share them with people. Now, why is that powerful? One, it’s great for content creators, it’s great for developers. But also, if you are in the business of building a platform business model that connects developers with users, This is a huge step up on the developer side. This means that the number of developers you have on your platform can increase dramatically, which is what TikTok did. So you get a big step up in terms of the number of users, in this case developers, in the case of TikTok content creators, that makes the network effect dramatically more powerful. Instead of having hundreds of thousands or millions of apps, you can have hundreds of millions because everyone starts creating all these little apps for every little use case you can think of. That gets you a long tail of apps. The same way TikTok has created a long tail of content where if you wanna look up anything on TikTok or YouTube now, you wanna look up varmint hunting in South Africa, which I’ve been looking at, which is actually kind of interesting. There’s… tons of content creators who only do that crazy little subject. You know, once you democratize content creation, you have dramatically expanded the long tail, which makes the network effect more powerful. It makes it a more robust product and service for users. Well, they’re doing the same thing in terms of software development. That’s Power Platform for Microsoft. And they bought GitHub. So they added a ton of professional developers. and they’re increasing sort of amateur developers. That’s what they’re doing on their innovation platform that’s gonna run on the web. That’s super powerful, absolutely. That’s platform number one. Platform number two, because I’ve said Microsoft is two platforms plus infrastructure. The second platform is their CCS platform, their collaboration, coordination, and standardization platform. This is where the two user groups on the platform are not users and developers. It’s people participating in joint activities. Like, we can go online and work on GitHub and work with other developers and create something more complicated. The purpose of the platform is to enable workflows that are more complicated. to sort of happen together. That’s the type of interaction of a CCS platform. So as I’ve kind of said many times, Zoom is an example of this. Zoom is a pretty weak platform actually, but it enables people to do collaboration online that otherwise they would have to do in person. So communication is a type of collaboration. Team based projects is a type of collaboration, which is why Microsoft Teams is called Teams. You could argue that Microsoft Word, Microsoft Office, Microsoft PowerPoint, Adobe, these are all tools that enable collaboration between parties, between users. That’s a different type of platform business model. Well, Microsoft is the same way sort of Power Platform is taking an innovation platform and moving it from an enterprise and a personal computer, Windows, to the cloud, Azure. Similarly, a lot of what they’re doing is taking a CCS platform and moving it from enterprise and let’s say Microsoft Office, also onto the cloud. So that is Microsoft Teams. There’s a reason Microsoft Teams is called Teams. It helps your team work together. as opposed to everyone has just got office. So there’s a whole suite of productivity tools that Microsoft is developing for the web. There’s a whole suite of communication tools. Microsoft Teams would be part of that. And they’re basically doing communication, productivity, collaboration tools. And the other tool that are sort of on the horizon for them are what we would call data intelligence tools, of which Snowflake is one, Databricks is another, where they are gonna help companies internally and increasingly externally collaborate because they have a shared data ecosystem. That’s all about collaboration. We all have the same data, we can all see the same data, we can all access the data with various tools in our company. We’d call that the single source of truth. That enables collaboration. So when you start looking at collaboration as a platform business model, you really see four types. You see communication, you see team-based projects, you see data ecosystem sharing, collaboration, and increasingly the last one you see is operational automation. If we have all of our company collaborating, sharing the same data, working on projects, that makes it… possible to start to automate processes that happen on their own. If you look at what Microsoft talks about, they are talking about communication, productivity, team-based projects, data intelligence, and increasingly they’re talking about operational automation. So it really lays out quite nicely. So that would be the second platform, and these two platforms support each other. So two complementary platforms, which is my favorite type of business model. That’s what they’re building, and they’re building it at global scale. Now, the last bit on this business model, and then I’ll move on to valuation, is I’ve said they’re doing two platforms plus infrastructure. The other thing they’re spending a lot of time on is building cloud infrastructure. Yes, they want the two most attractive pieces that are gonna run on this infrastructure, which are the two platforms I’ve just mentioned. but they’re also helping to build the infrastructure, which is cloud. They’re building lots of data centers, they’re building lots of AI tools. The analogy here would be, let’s say smartphone. When Apple launched the smartphone, they provided the infrastructure, which is the smartphone. And then they sell those and they make money. But they also took the two… two of the most attractive things that run on that infrastructure, which are the app store, and probably Maps and a couple other things. So one, they provided the infrastructure, two, they captured the two most powerful attractive business models, platforms, that run on that infrastructure. Well, that’s what Microsoft’s doing. They’re building the infrastructure and they’re grabbing the two most attractive pieces, which are the two platform business models I’ve just described. Now a company that didn’t do this, you could say is the mobile companies, the companies T-Mobile, Verizon. They spent a lot of time and money building the infrastructure, all the 4G, 3G towers, but they didn’t end up capturing the two most attractive businesses that run on that infrastructure. Other companies took that. Amazon took commerce, Facebook took social media, and these mobile networks like T-Mobile. they ended up just owning the pipes and you didn’t wanna own the pipes. Well, you had to do that, but you wanted to own Amazon and WhatsApp and Facebook and they didn’t get any of those. So Microsoft sort of going for the two most attractive platforms plus the infrastructure. That’s most of what I think they’re doing right now. And they’re doing very, very well. I mean, their business model makes a lot of sense. Okay, so that would be my assessment of the business. As you run through their various business lines, what jumps out at you is they’re building two powerful platform business models that by and large, now we jump to my sort of competitive thinking, which is, okay, who’s gonna dominate? Well, we can look at Azure, which is a cloud business, a global cloud oligopoly. Who’s gonna dominate in cloud? It’s very clear. It’s AWS, it’s Azure, it’s Google Cloud, maybe Huawei. Alibaba Cloud is big in China and Asia. You could say Snowflake and maybe gonna take part of that, but it’s very clear they’re gonna win this. So the competitive situation, this is a dominant business model, it’s an oligopoly. We can look at Windows, that is, and has been for a long time, a global amount. monopoly as an operating system. It’s on everybody’s computer everywhere. We can look at Office as another global, not monopoly, but in terms of productivity software, it’s an oligopoly. We can look at LinkedIn, which is pretty much when it comes to professional social networks, is pretty much the only one everybody in business has a LinkedIn profile. So we’ve got at least four. oligopolies or monopolies that I would all put at the top of my six levels of competition, I’d put those all at the top level. These are dominant businesses. And so Microsoft looks like, you know, three to four, if not five dominant businesses that all support each other. It’s one of, if not the strongest business model I can find anywhere. That’s kind of how I do my competitive assessment of this. Okay. That’s sort of step one. And I can’t do the valuation myself until I’ve done the qualitative assessment. Because I’ve got to sort of have a good feel for how this is going to play out. So I always do the qualitative assessment first, quality, and then I move to valuation. So let’s, I’ll do that right now. Now, in terms of valuation, I have one slide, which I’m going to put in the show notes, which I call basically valuation like Warren Buffett in one slide. This is how I do full valuation, where I run all the numbers. I do lots of different models. I take it apart. I just sort of boil the ocean. It’s just sort of my process. When I look at the quality of a company, I boil the ocean. I run through tons and tons of checklists. I do everything. Then I do the valuation, and I boil the ocean. I build out all the models. And then I step three, which I’ll get to it. the end is, then I put all that aside. That’s just me going through everything in my head. Then I put it all aside, I pull out one piece of paper, and I just write down what I think it is. So I sort of forget all of that, but I have to go through the process. So when it comes to valuing a company, especially a digital business, in this case I would use the Warren Buffett approach because we’re clearly looking at a high quality business. Now if you’re looking at a garbage business, I would probably, I wouldn’t use the Warren Buffett approach because he doesn’t buy garbage businesses. You might look at Carl Icahn, you might look at Seth Klarman, and they have a different approach to valuation because that’s the kind of companies they buy is sort of garbage companies that nobody likes, but they get them super cheap, and then they buy them and sell them pretty quick and make a little profit. Okay, this is for high quality companies, which Microsoft is clearly that scenario. So I have one slide, which is in the show notes. which is called valuation like Warren Buffett. And this is my assessment of how he actually does it. I may be wrong. I’ve been working on this for years and years. So if nothing else, it’s how I do it. And this is me boiling the ocean. If you look at the slides, which I’ll try and describe here, I basically do four main approaches. And you can put those into sort of two buckets. The first bucket is, what is the company worth today if nothing were to change? If time were to freeze right now and nothing were to ever change, no technological change, no competitive change, no growth of any kind, but the business as it is today gets frozen in time and just sort of goes forward as it is, what would that be worth? And the reason I like that approach is because, well, it’s unrealistic, because things change, but all the numbers I’d be looking at are real. I’m not making anything up in my head of what revenue may be or cost may be. I’m looking at the revenue and cost today, which I can see. That’s all very real data. So let’s just take the most concrete numbers we have, which is the revenue this year, and freeze it in time. and say if everything froze, this is what it’s worth. Okay, so that’s sort of one bucket. The other bucket is then I jump forward three to five years and I say, okay, what could the future look like with this business based on my assessment of its quality, its competition, technological change, and I don’t try and project from today to there. I really don’t do discounted cash flow almost ever. I don’t… predict next year’s revenue and the year after that and the year after that and then look at the capex. I don’t try and project forward year one, year two, year three, year four. I don’t do that for the most part. I just jump into the future three to five years and I draw a picture. This is what I think this company could look like and I do three to four scenarios and then I sort of value if that scenario happens, what would this be worth? and then you basically discount that scenario back to today to get a value. So I call that scenario building. And if you look at the slide I’ve put in there, the stuff in yellow, earnings power value, and I’ve written basically EPV and PG. EPV is earnings power value, PG is perpetual growth value. Those are very standard approaches to doing sort of valuation today. You can look them up online. And then I jump forward to the stuff in blue, which is on the right, which is just scenario building. And the scenario I’m really working on most is what I would call the minimum scenario. That in three to five years, this is the scenario which is the worst case scenario. If everything changes reasonably, if the Earth gets hit by an asteroid, that’s different. What is the minimum scenario for three to five years? And can I really get a solid picture of that? Often in a digital business, you can’t, because too many things are changing. In a company like Microsoft, with very powerful competitive advantages, I think you can get a solid read on the minimum scenario in three to five years. So I’m sort of doing those two scenarios. What is today? What is the future? And I really don’t do that sort of discounted cashflow where you build out a spreadsheet year one, year two, year three, year four. I don’t really do that. Now, that’s sort of my approach. Usually in the future, I’m trying to come up with two to three scenarios, but the one I’m focused on most is the worst case scenario. Let’s not say worst case, because you don’t wanna predict everything that could go wrong, but let’s call it the minimum case. I really don’t think it’s ever gonna be worse than this case. I really don’t. Based on my assessment of the business, the product. the competition, the tech, all of that, which falls out of what we just did, which is the qualitative assessment. And then I’ll look at best case, base case, and I’ll just build out three to four scenarios for three to five years in the future, compare that. And that’s kind of my approach. And there’s other stuff in there. If you look at, I will put a slide in the show, I’m sorry, a link in the show notes to an article I wrote, which is basically eight types of valuation. earnings power value, which I’ve talked about, perpetual growth value, scenario building in the future. The other ones I talk about are like reproduction value, liquidation value, explicit discount cashflow, rule out scenarios, but I basically have eight different versions that I do. And that’s me boiling the ocean and just running all of them. I’ve also given you how the NYU professor Aswath Damodaran. his approach, which I’ve studied pretty extensively. I put that in there. And then I even put in my slides for how I calculate this stuff. And I generally like to do this step with paper and pen and a calculator. I don’t use spreadsheets. I really don’t like using spreadsheets. I think it gives you a false sense of precision. If you can’t figure out the valuation with a pen and a paper, you probably shouldn’t be building a spreadsheet. Now, once you’ve done it with a pen and a paper, you can build out the spreadsheet. I think that’s fine. But I generally won’t do that until I’ve sort of done it by hand. Usually I’m sitting in a coffee shop with a piece of paper. And I’ll give you my one sheet of paper that I use to calculate this stuff. Okay, so that’s sort of phase two. I run all those numbers, see what I get. Now, the group that we work with here in Bangkok, There was a team that did Microsoft, and they basically did pretty similar to what I’m just saying. They did a little different, but they did a great job. And they sort of ran through all the numbers, and that was helpful, because I got to compare it to my own. And we were pretty much 75% on the same page on how we would address this. How do you figure out the future of cloud? How do you figure out the future of Windows? How do you figure out the future of gaming, LinkedIn, all of that? and you just sort of go through that process. So that would be sort of phase two, boiling the ocean. And I’m not gonna publish my version of that right now because I think that’s a bit too much. But let me just jump to the so what of this podcast. What is my evaluation based on that? Okay, so I get to step three. Step three is when I put all of this sort of ocean boiling aside, I pull out a piece of paper. Usually I sit down in a coffee shop, I have a cup of coffee, and I ask myself a couple questions. And I see if I can answer them confidently based on all this analysis, which is, here’s my questions. What are the key variables that determine the value of this company? I don’t want 50 variables. I don’t want 30. I want like 8 to 10 numbers that I’m going to keep an eye on. I’m going to calculate the value based on these numbers and I’m going to keep an eye on them. And this is me copying Buffett. He talks about doing this. So what are the key variables that determine value? Do it on a napkin. Question two, how predictable are these variables going forward? Some of them, like the revenue from Windows, is very predictable. Because you can go back 10 years, it’s very stable for the past 10 years, you can go forward. Other variables are far less predictable, like the revenue from cloud. Much less predictable. And I make a list, and it’s literally on a piece of paper, here’s the variables that determine the value. column two, here’s how predictable I feel they are. Now, that should sound a lot like, and here’s the other concept for today, that should sound a lot like birds in the hand versus birds in the bush. That’s the Warren Buffett thing, and I think that’s how he’s doing it. So, I just sort of decide on my list of paper which are the birds in the hand and which are the birds in the bush, and here’s what I get. I look at cloud. the Azure business which has revenue, which has EBIT, which has certain amount of CAPEX, which has a certain amount of growth, and I break that into two pieces. I say, I think the cloud business, assuming very low growth, that it’s not gonna change very much from today, I think that is a bird in the hand. I can look at certain variables to figure out its value, which is basically the operating margin is what I’m looking at. a growth margin of 2 to 3 percent and then maintenance capex against that business. That to me is a bird in the hand. I don’t, you know, I can see the variables today, I can track them and I think it’s very predictable if I separate out the growth. So the bird in the hand for me is the cloud business with a very low stable growth and the bird in the bush is additional growth in the cloud business. That is harder to predict. And I can put a number on that. And for the numbers I had for a bird in the hand for cloud, I put it at about $400 billion. 400, 450, maybe up to 500. I get that number mostly by during earnings power value and for perpetual growth value. That gets me 400 to 500. I am really pretty confident that that bird is in the hand. then I look at the additional growth, that look, this could grow a lot bigger than this, obviously. Okay, that’s when I start doing scenario building into the future, and I call that a bird in the bush, and I put that at anywhere between 100 and about $600 billion of additional value that may appear in the next three to four years. That’s the bird in the bush that may appear. Okay, so those are my numbers. I go down the list. Okay, what about office plus teams? which is sort of their stable productivity business. Again, that’s for me is another bird in the hand. I put that value at about $300 billion. The variables I look at, which I think are very predictable, market share, revenue, operating margin, which is EBIT minus taxes, standard growth of two to 3%, which would imply certain capex spending. Again, I think that’s bird in the hand. $300, $200 billion, I feel very confident about that. I don’t even consider any additional growth in that business. I could, that could be another bird in the bush, not gonna do it. Number three bird in the hand is the Windows PC business, which again has been around forever for this company, very predictable. Looking at sort of EBIT for that business, revenue for that. I think that’s high predictability. I put the value at about 250 to $300 billion. Okay? The other bird in the hand, so that’s one, two, three, four birds in the hand would be LinkedIn, which is a small business. I put it at about $40 billion. Anyways, that to me, you add those numbers up, you get $1.2 to $1.3 trillion. That to me is… bird in the hand for Microsoft today that is overwhelmingly based on looking at the earnings power and perpetual growth value of the business as it exists today. What’s the bird in the bush? That’s what could appear in the next three to five years. It’s less predictable, but should be aware of it. That’s mostly additional growth in the cloud business and maybe additional growth in things like gaming and office and teams. I put that at about $100 to $600 billion. So net-net, that’s where I end up on this one. 1.2 to 1.3, I’m very confident about between 100 and probably 600 to 7, which would get you up to a total valuation of about 1.8, 1.9 trillion if you add in all of the birds in the bush. That’s where I end up. The market cap as I’m doing this today is about 1.8. So you know, I put this on my watch list. Now let me put the huge disqualifier disclaimer right now. I am absolutely not saying to invest on this company based on these numbers. I am not sure I’m right. These investment numbers could be wrong. Don’t take my word for it. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. I very well, these are ranges and estimates and projections. Totally could be wrong. And a lot of this is opinion. It’s not science. So that’s my big disclaimer. This is not investment advice. Put that there. But based on that, I get to the point where it’s like, okay, it’s trading at about 1.7, 1.8 right now. That sort of factors in a lot of the growth, the birds in the hands I’ve already calculated. There are some people that think this thing could be 2.5 trillion, right? A lot of people think that. So they think buying at 1.8 is a good idea because this could be worth 2.5. You’ll hear that all over the place. I sort of put this at, you know, 1.2 to 1.3 has a minimum. 1.8, 1.9 factors in most of the birds in the hand bush that I’m looking at. So what am I going to do? Well, I’m, you know, I’ve written this number on a sticky, it sits on my computer and I keep an eye on the stock price. And if any random day it gets into a range that I feel good about, maybe, you know, maybe I’ll do something. And I think this is how Buffett does it. I really do. I think he looked at a company like Coca-Cola, which he bought big in the 1980s. I think he had a price in mind, a value in mind for that company for a long, long time. And then I think he waited and waited and waited. And then one random day, you know, the market shifted down and he went in big. You know, he bought a lot of Coca-Cola in the 80s, such that the CEO of Coca-Cola heard about somebody buying. And apparently he did call Buffett and said, you know, we’re seeing a lot of purchasing of our stock. Is that you? And I guess Buffett said, yeah, yeah, that’s me. So, you know, this is a sort of come up with a value in your own mind and then you sit and you see and you wait. And that’s probably where I am with Microsoft right now. I’m waiting. And I’ll see where it goes. But anyways, big disclaimer, this is not investment advice. If you end up buying or whatever, I could totally be wrong. So don’t get mad at me, do your own numbers, do your own research, but I’m gonna more and more take you through how I come up with numbers for these things, and this is the first one. Pretty complicated company. One of the reasons I like Microsoft as a company to look at, and I’m gonna look at Amazon next, is there is a degree of complexity in the business model that I think a lot of people are not getting right. I’m looking for something where it’s like, it’s not so hard I can’t figure it out. but it’s complicated enough that I think a lot of people might be getting it wrong. So I’m looking for a business model that has certain complexity where I feel like it’s in my area of expertise. And I think Microsoft is definitely there. Amazon, not quite as much the business model is more straightforward. So that’s kind of what I’m looking for. And then, yeah, that’s what I’ll be doing going forward. So this is the first one in terms of valuation. You have my sort of thinking on this. I’m probably not gonna put any spreadsheets in there, but I’ll tell you what I’m thinking back of the envelope calculations. Yeah, and we’ll see. And I think that is the content for today. I hope this is helpful. And going forward, we will do probably 70% analysis of company quality business model strategy, which is my strike zone. And then 20 to 30% some valuation of those same companies. And hopefully that’s a lot more valuable to people. Let me know what you think. And if you want to be involved in sort of these valuation calculations, send me a quick note on LinkedIn and I’ll get you roped in because we’ve got some people working on this and we’re ramping up the Amazon assessment valuation calculations right now. So if you want to be involved in that, send me a quick note. But that is it for the content for today. As for me, today’s going to be a pretty awesome day. I’m going down in about two hours to the land office. here in Bangkok to sort of complete the purchase of my new condo, which is, you know, it’s kind of funny how this is all happens here is it’s very sort of old school where you have to go down to the government office and they literally have land titles on physical paper in the office. And on the back of the land title, in this case, it’s, you know, condominium, there’s a list of owners, including, you know, the bank that did the mortgage. And they basically you go down and you have to bring cashier’s checks. and you bring your lawyer and the seller comes down and a representative from the bank, in this case the seller’s bank because they had a mortgage, you all have to sort of meet together and the check gets handed, the land title gets physically changed. There’s a government person who literally stamps the next name on the back of the listing, this person is now the owner and you have to do it all at once in person. It’s a pretty great system actually, it’s totally non-hackable. Like there’s no way to hack it. And then the file goes into a folder at the office and it stays there. So I’m gonna do that in about two hours, which is fantastic. I’m really excited about this. This is kind of my dream condo, my dream home. Basically ended up taking the top floor, about a third of the top floor of this building, which is up on sort of the 22nd floor. And it’s, yeah, it’s just, I counted it, it’s seven windows and two balconies that overlook the park. So I have all this sort of view of the park and all these, and I have no idea what I’m gonna do with all this space. I’m gonna put in a theater, I’m gonna put in a formal office. So it’s too much space for me, but it’s gonna be fun. Anyway, so I’m really excited about it, just sort of fell in my lap and yeah, go figure. So that’s today, gonna be a great day, I think. And then I gotta get this all done and then I’m heading out to Malaysia and then down to Singapore for the first second week of January, doing some meetings down there. So back on the road. Yeah, it’s gonna be exciting. So that’s it for me. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope this is helpful. Let me know what you think about this sort of new focus on company analysis plus valuation. Hopefully that’s gonna be more helpful, but let me know what you think. I’m always reachable on LinkedIn or email or whatever. So anyways. Hope everyone’s doing well, and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.