This week’s podcast is about core vs. adjacency growth. This is a good framework for thinking about growth in digital businesses’.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Most of this is a summary of work by Chris Zook at Bain’s strategy practice. I am citing the books:

Most all sustainable growth is based on 1-2 strong cores.

- A profitable core is centered on the strongest position in terms of loyal customers, competitive advantage, unique skills, and ability to earn profits.

- My list for strong cores are growth / market, competitive advantage and attractive unit economics.

- Adapting the core can be:

- New products / services

- New customers – microsegments

- New geographies

- New businesses.

Six growth adjacencies:

- New customer segments:

- Micro-segmentation of current segments

- Unpenetrated segments

- New segments

- New geographies

- Global expansion

- Local expansion

- New channels

- Internet

- Distribution

- Indirect

- New products

- New to world

- Complements

- Support services

- Next generation

- Just new products / services

- New Businesses

- New to world needs

- New substitutes

- New models

- Capability adjacencies

- New value chain steps

- Forward integration

- Backwards integration

- Sell capability to outside

How to assess an adjacency move:

- Factor 1: Adjacency is tightly tied to a strong core.

- Economic distance is short. How much does it overlap?

- Need a strong core or a strong position in a channel, customer segment or product line in weaker core.

- Usually the linkage is considered superficially. Snapple is close to Gatorade? Production is totally different. So are customers and advertising. And points of purchase and distribution.

- Factor 2: An attractive adjacency market in terms of profit pools

- Factor 3: The ability to capture economic leadership in that market. Competitive advantage as an attacker and then an incumbent.

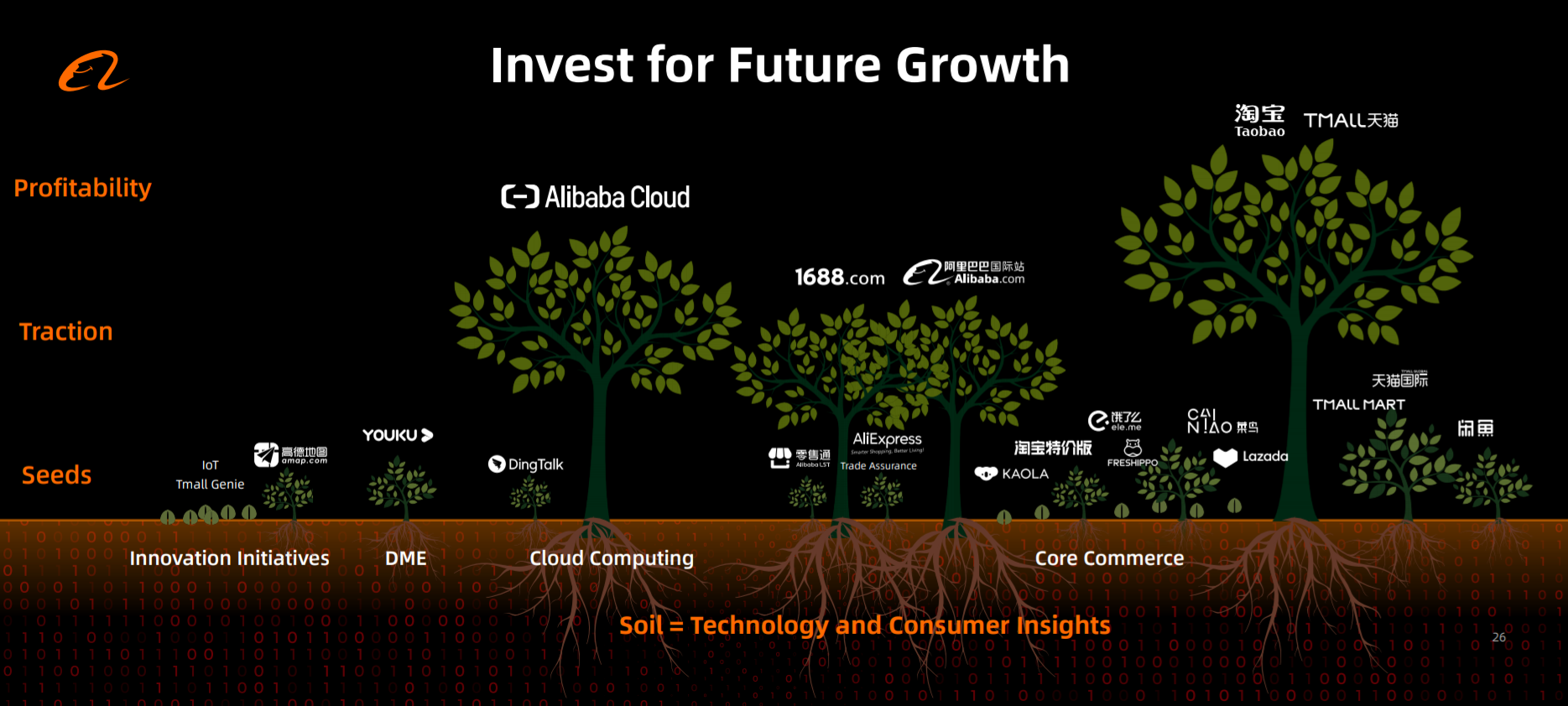

Digital adjacencies are moderate, relentless expansions versus big trees.

A great quote from Beyond the Core

——-

Related articles:

- Growth, ROIC / RONIC and Growth + Sales in Digital Valuation (Asia Tech Strategy – Podcast 102)

- An Intro to Growth and “Birds in the Bush” in Digital Valuation (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Growth: Core vs. Adjacency

- Digital Operating Basics

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

Photo by Volodymyr Hryshchenko on Unsplash

———-

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

—–Transcription Below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson, and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, core versus adjacency growth in digital businesses. So this is going to be really about growth, which has kind of been this through line for a lot of topics that have come up, like tactics. We talked, or I talked a lot about sort of growth hacking, virality. I talked about growth plus sales a couple weeks ago. I mean, these are sort of shorter term moves, but growth is the objective. We talked about digital operating basics, just sort of getting the basics right, of which the first one on the list, if you go back and look at that list, was growth and scale. I’ve talked a lot about operating leverage, that a lot of software businesses in particular are about sort of getting operating leverage to kick in once you start to get to a certain level of size and you’re… Gross margins in particular start to take off. Competitive advantages, economies of scale getting bigger than your competitor. Well, that’s an outcome of superior relative growth. And a couple weeks ago, I talked about sort of valuation and you have to basically compare value created as linked to. growth and return on invested capital, or return on new invested capital, but those three ideas, value, growth, R-O-I-C, R-O-N-I-C, they all sort of link together. So it’s kind of been a through line, this idea of growth, and I mean, let’s be honest, anytime we’re looking at a digital business from an investment perspective, the growth question comes up almost immediately, because usually the basics are already priced in, and you’re sort of estimating, like, how much is Shopee really gonna grow in the next two years? in Latin America or now in Poland. It’s usually that growth question that matters. So I haven’t dug into it too much because it’s kind of a big subject. I have pointed you to a McKinsey book on valuation, pretty huge textbook, McKinsey Valuation. They have a particularly good section on thinking about growth and when it creates value and when it doesn’t. But probably my go-to. for thinking about growth when it relates to digital businesses in particular is this idea of the core versus adjacencies. And kind of the big thinker on that subject is a guy named Chris Zook who is at Bain. And he wrote books on this 20 years ago, 20, 25 years ago, there’s a book called Profit from the Core, I think that’s about 2001. He wrote another book called Beyond the Core in 2004. Both of them are, I think, are particularly good and they are really helpful when you start thinking about how a digital business is gonna go forward. So I’m gonna kinda summarize his thinking today and then he wasn’t really talking about digital businesses and I’m gonna adapt it to where I think it matters when you’re talking about software and stuff. So that’ll be today. So that’s a bit of a, I guess a long tee up for this. But I’ll put the link in the show notes to those books. I think they’re both great. I read them every couple years. And that’ll be the topic for today, how to think about core growth versus adjacency growth within digital businesses. Now, for those of you who are subscribers, I sent you a pretty decently dense email in the last day or so about that new company I said you should put on your radar and start looking at. Like really start looking at it. I kind of took me a long time to take that apart and sort of figure out how to think about it. And I’ve been reading a lot about other people who’ve talked about it. A lot of people are talking about it and I don’t think anyone’s really figured out the business model that clearly. I think maybe I’m a bit ahead of the curve on this as far as I can tell, who knows. But there’s going to be a third part in that installment coming in the next couple days and it’s going to be about the growth aspect. And it’s really going to come down to core versus adjacency growth. That is a good way to think about that company. So that’s what’s coming next. For those of you who aren’t subscribers, you can feel free to go over to jefftausen.com, sign up there. There’s a free 30-day trial. See what you think. Join the group. Oh, one new thing. We’ve been doing sort of bi-weekly online calls or in-person calls looking at companies over the last year or so. And we’ve moved them to Zoom. This was just kind of a local Bangkok thing we were doing. We’ve moved them to Zoom. I think we’re going to open that up to everybody. So if you’re interested in doing that, this would be about every two weeks we would have a call. We’d look at a company, and we’d talk about it. And it’s usually, I don’t present the companies. Maybe I give some feedback, but people present the company. So it’s more of like, you do it, as opposed to just listening to me drone on. So if you’re interested in doing that, I will. put up a link at some point in the next week or so. Or just send me a note or put a note in the comments. If you put a note anywhere in the website in a comment, I’ll see it. Just say, yeah, please sign me up or something like that. And we’re going to start doing that, I think, in the next week or so. So anyways, that’ll be fun. OK. That’s kind of housekeeping for today. Last thing, standard disclaimer. Nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinion expressed by me may be no longer relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Now as always, there’s a couple key concepts which are always found in the concept library. Number one for today obviously is core versus adjacency growth. I’m going to start building out sort of the growth section of the library. I would say this is kind of the most important aspect of this, especially in terms of valuation. So that’ll be one. The other one we’ll talk a bit about digital operating basics, which is already there. We’ve talked about that a bit. So those are the concepts for today. Core versus adjacency growth, digital operating basics. They’re listed at the bottom of the show notes. Now, I mean, the growth question is interesting because growth cuts across everything. competition, value, future, all of that. It’s also kind of just, I mean, you could almost call growth like the organizational imperative. It’s just, it kind of drives everybody’s behavior. Have you ever been in a slow growing company? It’s just not the same. You don’t tend to get the best people. The best management doesn’t wanna be in slow growth or flat or even declining growth companies. If you’re not growing, people don’t tend to stay. There doesn’t tend to be as much focus. To me, growth is kind of like, a lot of business I think about, you’re just kind of a ship on the ocean. You’re trying to go from point A to point B and sometimes the water’s clear and you’re doing a lot of paddling or whatever. Some days you’re doing, the seas are rough and there are storms. Generally speaking, being in a faster boat moving forward or being in a bigger boat is just better. So, you know, it’s like speed, growth, scale. These are all just sort of, I don’t even talk about these as different competitive dimensions because I just think every company has to do all of those. Growth and speed are just kind of like, that’s just what a business does. The boat goes forward. Generally that makes life easier as opposed to sitting still, even in sort of let’s say rough waters. So that’s kind of a big deal. How do you grow? How do you grow? Now the flip side to the growth question is as you get bigger, organizational complexity goes up, which is sort of has traditionally been the bane of businesses. You get more people, because the operations were people-based. You get more people, you get complexity, you get bureaucracy, you get dysfunction. Now this is why the advantages of scale go up for a certain while and then they start to be overcome by what you could call internal coordination costs. And that’s been kind of the story of business for 100 years. Now I have teed up the question of, if you look at my Smile Marathon, the M is machine learning and zero human operations. And the idea is if you remove all the humans from the operations, complexity and scale don’t seem to become a problem anymore. So it might be that the advantages of scale go up and up and up when you don’t have people. And it’s just software or AI. But traditionally, no, I mean, as you got bigger and bigger, companies with more and more products, more and more services, more and more people, more and more operational footprint, they start to get dysfunction. So growth is the imperative. it’s also a bit of the bane of business. And so a lot of companies that do well at a very large scale, you often see the same pattern, which is, yes, we’re very big, but we also have a simplicity to our business model. We’re Starbucks. We’re big, 20 plus thousand outlets or whatever it is, but it’s also pretty simple. as a business. So that’s kind of been the counter balance is let’s get big but we gotta keep it simple. We don’t wanna be Yamaha that makes everything from saxophones to cars to, well they don’t make cars, motorcycles. You know, that’s how you sort of shed complexity as you grow. But generally, okay, growth is still the imperative. It tends to drive financial performance in a major way and it’s a competitive strength. I mean, if you ask CEOs what are they most worried about, on the short list will be when their competitor is growing faster than them. It’s a huge driver of M&A. You know, why did you do a merger? Why did you do an acquisition? Because our competitor was growing faster than us and getting much and much bigger than us. You know, and that’s when you start getting economies of scale. So in this, I’m gonna cite some of Chris’s books. One of them, profit from the core, he talks a lot about Nike and Reebok. And what he did, which was very clever, was they looked at company pairings. So they looked at companies that were effectively the same size and performance at one moment in time, and then they looked at them five to 10 years later. And when one of them grows faster, it really adds up. So he talked about Nike versus Reebok, which in 1989, 1990, were effectively the same size company, almost exactly. but Nike was growing faster, not 20%, but let’s say five to 10%, I’m making that number up, versus zero to five percent. And that’s really how I think about growth. I think about growth as zero to five percent versus five to 10%, I put it in two buckets. You add the fact that Nike was at five to 10 versus zero to five, and suddenly over 10 years, Nike just dwarfs Reebok. So it’s a lot like investing, is you wanna think about time. Time plus growth as a major determinant of company performance and strength and financial returns. Okay, so it’s a big deal. Okay, so how do you break it up, growth? Well, their argument is Chris’s argument. You break it into the core versus adjacencies. And that first book, Profit from the Core, that’s about core growth, and the second book, Beyond the Core, that’s about adjacency growth. They did pretty good studies looking at lots and lots of companies, hundreds and hundreds of companies over time, and they looked for sustainable growth. Not a couple good years, not a burst, but sustainable growth five, 10 years, when this value can be created. And they said, look, as far as we can tell, I’m paraphrasing, obviously, most all sustainable growth is based on one to two strong cores. A profitable core business is really what drives it. It’s not a bunch of weak businesses, it’s not a big conglomerate, it’s not a bunch of strategic moves left, right and center. Sustainable growth seems to be mostly driven by a company with one, two, possibly three, but probably not. one to two really strong core businesses, that’s where the growth comes from. Hence their focus on what’s your core, what’s your core. And I’ll talk about that, but what can be a core? They point to a couple, these aren’t really the ones I would look at, but they point to particularly loyal customers, I would call that revenue side scale, demand side scale, competitive advantage, unique skills or capabilities. the ability to earn profits, that’s their list. I don’t usually use that list. I usually talk about three factors, which are a large and or growing market, a strong competitive strength and defensibility, and positive attractive unit economics. Those are generally my three factors you’ve heard me talk about. And some businesses have one, some have two, and a rare few have three. If you have all three, That to me is a strong and growing core. That’s Starbucks selling coffee. That’s a search engine. That’s a marketplace platform. Now their approach to the core is, yes, you need a strong core and you need to sort of assess how strong is it. You can use either of those frameworks I just said, my sort of standard three or theirs. Chris talks a lot about highly differentiated businesses. I don’t really use that term because I don’t find it terribly useful. Okay, that’s the core, focus on that, but going hand in hand with that, if you want sustainable growth, you have to be able to adapt the core. So there’s his sort of mantra over and over, is like focus on the core, but also understand that you will have to adapt it over time against changing customer behavior, changing market conditions. But this is more of a slow gradual process. And the two points they sort of think about adaptation of your core is innovation and closed loop learning, which I’ve kind of pretty much talked about the same thing, but you know, stay close to your customers, keep testing them, understand the landscape is going to change, understand that Walmart today is not like Walmart 10 years ago, but it’s pretty close. You would call it the same core business. You would just recognize that it has adapted with time. Because you’re talking about 10 years, that’s when this thing is gonna pay off. How do you adapt? Well, you offer new products and services. You recognize that you’re gonna have new customers. You’re probably gonna start looking at sub-segments of customers. And Chris talks a lot about micro-segments, that probably your go-to best way to generate growth in a core business. is to look at your current customers and start to segment them into smaller groups and serve them in a more personal way. Now digital, we go to an extreme because we talk about market of one. Every customer is their own market. But traditionally, you’d look at a company like a bank, financial services companies, insurance companies, they would always do micro segments. Dell Computer is kind of famous for saying, how do you grow Dell Computer? And Michael Dell’s like micro segments. We always look at our customer base and we segment them and serve them each better. You could grow the core by new geographies. Hey, we’re China, we’re Starbucks, we’re going to China. Or you could do new businesses. But all of those would be just sort of general adaptation, not major moves. So I would call that all core adaptation. Okay. I think that’s fairly easy to understand. One of the things they talk about, well, Chris, I guess it’s not they, I think it’s he, mostly one person, why does a company stop growing? Why does it stall out? And all companies do this. I mean, there are very few companies that grow three, five, seven percent per year for a decade. Most of them stall out at certain points, regain their growth at other points. They did some pretty good studies on this and said, what’s the number and reason a company would stall out in growth and they said it’s losing focus on the core. They start to get distracted. They start to see greener pastures. They start to see the other company’s doing this, we should do this. They sort of lose focus on their core. And the other reason they pointed to was a failure to adapt to changing times, but really like 70, 80% of the time. it’s losing focus on the core, not failing to adapt. So the takeaway from that, build a core business, focus on your growth there, continually come back to the core to find new sources of growth within your core. That is strategy number one, two, and three. As you go along with the core, realize you’re going to adapt. That is gonna be more rapid in some businesses than others. But let’s say we’re looking at a digital business, e-commerce, we could look at a company like Shopee. Their core business was gaming. They’re focusing on that. They’re adapting it in Southeast Asia. They’ve been doing that for almost 10 years. They did one major move outside of their core business. They went into e-commerce. We could call that a second core. And I think they’ve basically been staying within that core for a good six years now. They’ve been adding new geographies. We could call that adapting the core, but they’re not making a major move into something else. Now they’re in Poland, which is pretty interesting, Mexico, Brazil, but it’s still sort of focusing on that core. It’s one of the reasons I really like that business because they’ve got two strong cores. Okay, a couple last points on this. There are exceptions to this. where you do see, sometimes you see what we would call strong followers, like American Express versus Visa and MasterCard. American Express was actually ahead of Visa and MasterCard in launching in the 60s, but they were largely a follower and still are a follower to Visa and MasterCard in the credit card business. So they’re a strong follower, but they’re doing very, very well. Toyota versus GM, sometimes we see these sort of strong followers which can be interesting even though they don’t really have economic leadership in the market. Probably the biggest problem within this whole thinking of the core is when you see businesses with fuzzy boundaries. And it’s hard to sort of argue what the core is because no one can agree really what the industry boundary is. You know, is Walmart about… hypermarket retail, big box retail, or is it more about serving the customer wallet, which you could define that in a much broader way. And if you define it that way, you’re suddenly starting to think, well, maybe we should do financial services too. Look at all these customers we have in Bangkok or wherever. So when you have fuzzy boundaries for a business, like communications, media, this gets a little harder. But that’s kind of how you can think about the core. They did some pretty good studies on this and they show a couple things like if you have a weak core business doing a major adjacency move, jumping into another business almost never works. And you see businesses do this all the time. When they’re in a weak core business, they always try to jump to something else. Never usually works statistically, they say. If you are going to do adjacency moves, which I’ll talk about next, the number one determinant of success, the reason you don’t want to do a lot of adjacency moves, let’s jump from gaming into e-commerce like Shopee. Yes, you can get growth, but your risk of failure is like 75%. That’s the number they talk about. It only works about 25% of the time at best. So it’s a much lower probability move. That’s why you’re better off focusing on your core. The number one determinant of success in a significant adjacency move is having a core strong business, a strong core business you can bolt it onto. So if you have a strong core, that’s great, and it also makes your probability of success with an adjacency move much higher because you can tie it to your core business, which is kind of what Shopee did, right? They built Shopee in Southeast Asia off of Garena. the gaming business. The one strong core made the probability higher. So that’s kind of point number one, just think about what is the core business, how would I define it? Is the company focusing enough on this? Do they have a long runway of growth here? And usually people underestimate how much you can grow your core. And focusing there is, you know, strategy number one, two, and three. All right, then we move. to sort of the next topic, which is adjacency growth. And really, these are tied together, right? So a growth strategy would be core plus adjacency plans, moves, things like that. Growing the core, very, very important strategy, one, two, and three. Some cores can grow more than others. Some are somewhat limited. It’s just the way life is. Some are stronger, some are weaker, and here’s the so what. Some of them have more adjacencies than others. Digital businesses have a lot of adjacencies. If you’re Starbucks, there’s not a lot of adjacencies you can do. You can grow your core, we can add stores, we can move into selling some beans and some things, but you’re not gonna jump into media, you’re not gonna jump into banking, you’re not gonna jump into healthcare. Those adjacencies are, there’s just not that many of them. Good B2C businesses and good B2B digital businesses have a lot of adjacencies. It’s one of the awesome things. So, you know, the course, you know, the kind of key strategy here is grow the core and consistently jump into closely adjacent areas. That’s your strategy. And you don’t do it once, you don’t do it twice. I mean, you wanna be doing adjacency moves, let’s say two. two to three times per year over time, because again, 75% of the time, it’s not gonna work. So this is a, we do it over and over and over and over. One, that means 25% of the time, let’s say we succeed, so we have to do volume to get that. And it’s like M&A, people always say M&A always fails. It’s not really true. M&A is just, M&A fails as a company strategy when you don’t do it consistently because you’re not good at it. When you do something repeatedly, like GE does a ton of M&A, you get better at it. So you wanna be doing adjacency moves two to three times a year, just so you’re good at it. If you do it once every two years, you’re not gonna do well. You know, you gotta swing the bat on a regular basis. So, grow the core. plus consistent jumping into closely adjacent areas, that’s your strategy. Now, one of the things Chris talks about a lot is why jumping into adjacencies is actually notorious for killing companies. It’s like famous. They cite the thing like they looked at business disasters between 1997 and 2002, and they said 75% of the most notable business disasters, corporate CEO-led disasters, were because of adjacency moves. That company CEOs, management teams, they abandoned their core. For whatever reason, we’ve gotta do this big move. They jump into this new thing. They lose focus. They sap the energy and resources from their core. They under invest in their core. They get kind of dazzled by adjacencies and that causes problems. So number one, number two strategy, continue to mine the core for more profitable growth. Strategy number four, relentless, repeatable adjacency expansion, but not at the cost of losing your focus on the core. So one example, these are all from Chris’s books. Dell famously in the 1990s when they were rocking and rolling, moved into opening retail stores. That would be a major adjacency move. We’re gonna create a new channel. And I’ll give you six types of adjacency moves. They jumped into that, it didn’t go well. They sapped to their focus from the core. And to their credit, they then abandoned these retail stores, closed them down and went back online. So that would be a failed adjacency moves. And generally management teams wanna be daring. People are over optimistic. When you think about an adjacency move, you wanna think about it like going to war, like planning an invasion. Like you wanna plan it with military precision. And most of your planned adjacency moves by companies are kind of fuzzy thinking, we’ve gotta do it, we don’t have a choice. Investment bankers are pitching these deals. It creates a lot of cost, it creates complexity, you lose focus, you subsidize it with the core. You just need a much higher threshold for when you do these things. And you need to think about it like invading the country next to yours. You don’t do it lightly. Okay, now, last point on core plus adjacency as your. strategy for growth. Chris talks a lot about the new math of sustainable growth. And this is important, I mean, investors will recognize this math very quickly. Yes, every now and then you’ll get a company that grows like a rocket ship. Those are awesome, but they’re not that rare. I mean, they’re not that common. Nike, Amazon, Google, rocket ships for growth, fine. If you can pull that off, that’s awesome. Most companies don’t get that. What most companies have to go, that’s like having a 10X return on investment. If you can get one, that’s awesome. That’s not your basic approach. Your basic approach is go for consistent growth over five to 10 years that compounds in value. That’s your Warren Buffett consistent growth. It really adds up over time. Companies wanna do the same thing. Your standard company. going to grow at about the rate of GDP, 2%, 3%. That’s standard baseline behavior. If you can do core plus adjacency growth and move that number from 3% to, say, 5% to 7% per year consistently, suddenly you start to really dramatically improve the growth of the company over 5 to 10 years. Same idea. So. A standard company growing 0 to 5%, that’s great. If you can grow 5 to 7 to 8% in a sustainable way, year after year, using growth in the core plus adjacency, you can triple your shareholder returns in 10 years. The growth adds up. Sustainable, consistent growth is what you go for. If you can pull out a rocket ship from here to then, here and then, that’s awesome. So. What you really want when you’re thinking about this growth strategy is not awesome, spectacular moves that everyone goes, oh my God, that was amazing. Look how they jumped from Garena to Shopee. What you want is relentless repeatability, reliability, a reduction in cost, a reduction in the rate of failure in your growth moves. You want to be, you don’t want to be the person swinging for the home run. You want to be the person that hits a single over and over and over. They, very low rate of striking out. Same idea. Decrease the risk of failure, do it consistently, try and move that failure rate of adjacency moves from 75% down to 40%. Anyways, that’s kind of the key strategy, what he calls the new math of growth that you get from a strategy like this. Okay, so point number one. Core growth, point number two, you add core plus adjacency growth and you get this sort of new math of growth. Third point here is, okay, what’s an adjacency? How do you figure out if it’s useful? What do you think? They list six types of adjacencies. I don’t really, I mean, I agree with this about 70%. I’ll talk about how it’s different in digital. I think it’s a solid move for a lot of traditional businesses to think about it this way. So they basically talk about six, I’ll just read them to you real quick and then go through them, new customer segments, new geographies, new channels, new products, new businesses, and new value chain steps. So six. New customer segments, first one. That’s gonna be your go-to. That’s gonna be, if you’re gonna look at any of these, that’s the one you look at. Now, how do you find new segments? Well, we could go to somewhere completely different. Now, we could go from serving B2C customers to B2B customers. And the example he points of that is Staples, which is sort of a. a big retailer in the US that sells a lot of office type equipment, paper, pens, things like that. Well, I mean, they basically set up a delivery business in a famous sort of adjacency move. They set up a delivery business so they could serve small businesses. So that’s an entirely new customer segment, but they’re using their same infrastructure and store footprint. So they didn’t change the structure of their business. They just changed, they added a customer segment B2B, you know, small businesses. So you could go after a new segment. You could go after, I mean really the big one here is what I mentioned before is we start looking at smaller segments of your current customers. You start to mine your current customer base and say look, you know, we’re a makeup company. Turns out we’ve got a lot of young moms in our customer segment. Let’s start to tailor our services to that smaller segment. So micro segmentation has sort of been the go-to strategy for growth for a lot of companies forever. Well, as I’ll talk about, that’s really, when I talk about digital operating basics, what are the basics of operating at digital business? Growth is number one. Number two is personalization. It is a big, big lever of a data-driven world as we start to personalize segment by segment and really down to customer by customer. That’s the Netflix strategy. Your Netflix is different than my Netflix because it is tailored specifically to you. Well, that is an extreme form of micro-segmentation. It’s the number one go-to growth strategy for most digital businesses is personalization. He’s basically saying the same thing. Your number one adjacency move should be new customer segments. First on that list, micro-segments. Same exact idea. Okay, that’s number one. Number two. major adjacency move. Now these are kind of similar to growing the core they’re just bigger. Number two new geography. Okay that’s that’s Starbucks moving into China. When Starbucks went from Texas to California I would call that growing the core. When they went to China that’s a major strategic move. That’s a new geography global expansion. We can view it that way. Another type would be local expansion. The example he talks about is enterprise rent-a-car. You know, used to serve customers in the US in towns and suburban locations. They did a major adjacency move when they said, we’re gonna go after airports. And they ended up buying a couple companies. So they’re using the same fleet of cars, the same IT. But they went for a new geography, which is we want to be at all the airports. And they did quite well. Third adjacency move, new channels. We see this a lot. This is I’m a retailer, I’m going online, new channel. So you could have internet as a channel. You could work with new distributors. You could go through resellers, things like that. When we see a company like Xiaomi, start to open retail stores or Apple did the same thing when they opened their own stores. That was a major, moderate adjacency move. A lot of this is just going online these days. Number four, new products. You could think about, I don’t know, just general new products like Procter and Gamble. I mean, they’re always introducing new products. Unilever. You know, they’re consistently adding new products, new products, new products. 3M, which is famous for using its technology, to, you know, they’re doing filters and water filters and air filters and Post-it notes and all those sorts of things. You know, they’re kind of more technologically-based new product development. Company like Unilever and Procter & Gamble are more about, they’re not really in the tech business, they’re more in the brand extension business. Same thing. You could do, so that would be sort of, let’s say, new products. You could do services tied to products. PetSmart, which was a big retailer in the United States, you go there, you buy products for your dog or your cat. They started to add services in a major way. Grooming, other things that you could do. So they went from a major adjacency from products to services. Support services, we see this with. digital businesses all the time. They offer hardware, software, and services. That’s the standard IBM model. What do we sell? Hardware, software, and services. Well, those are three different things, really, but they all sort of help each other. You can go into compliments, which are a big deal. Digital compliments. You could argue that the smartphone is a traditional product that they added a ton of digital compliments to, which pretty much everything in the App Store. Next generation stuff. Okay, here’s the old iPhone, here’s the new iPhone, and then new to world products, stuff we haven’t seen before. That’s Apple in the 2000s. iPod to iPad to iPhone to ITV. Steve Jobs was very good at new to world products. Tim Cook, not so good at this. All right, last two. New businesses. You can think about just new business models. This is a place where digital tends to do very well, where we just see a new business model we haven’t seen before. Bike sharing would be one of those. Luck in coffee, and the most half of what I’ve been talking about for the last year is new digital business models. That’s kind of a big one. You could sort of call it. Capability adjacencies. When a company builds a new capability and they just rock and roll with that, I would put ByteDance in that category. What ByteDance really does is AI-based matching. That’s what they do. They’re very good at it. They write the algorithms. They have all their engineers. They started out with a product that was a news aggregator. You could see lots of headlines that would be relevant to you because their AI-based matching was very good. Then they applied it to short videos that got them TikTok. Now they’re applying it to education. Well, before that got killed off. Gaming, music streaming, but they’re applying their core capability to one adjacency after another. So we could call that a capability-based adjacency. That’s where a lot of their growth is coming from. Last one. new value chain steps, and I’ll put the list of these in the show notes, by the way, these six. Moving up or down the value chain, forward integration, backwards integration. We see that all the time. We see this in healthcare in the US all the time, that every couple years, well, let’s say every 10 years, insurance companies say, we’re going to get into the provider business and open hospitals. They do sort of forward integration. It always fails. It never works. And we see major healthcare companies always try to backwards integrate into insurance. That almost always fails with the exception of Kaiser in California and other places. We see that on a fairly regular basis. The digital world, this is a big deal because one of the things new digital tools and trends do is they reshuffle the value chain. And the value chain we’re used to, manufacturers, suppliers, supply chain, distributors, retailers, customers, marketing, after service. That could be a typical auto dealer, that could be a Walmart. Digital tools tend to reshuffle that, and suddenly we see direct to consumer models popping up, we see social media, we see a lot of weirdo stuff. So when you see digital tools start to reshuffle the value chain, we can see some stuff there. The last one within new value chain moves. is when you start to sell your capability to the marketplace. And I’ve talked about this kind of a lot, when we start to see companies externalize a core capability. The famous example is Amazon. We built a lot of servers. Let’s take all our servers, this capability, and sell it to the marketplace, and we’ll call it Amazon Web Services. We see that move fairly frequently. So those would be the six they point to. Within those, those are kind of the ones I flag where I think you see a lot of adjacency moves in digital businesses. I’ll put that in the show notes, the six, and I’ll also put the ones I’ve flagged as areas I think are relevant to digital. Let’s say more relevant to digital. Okay, last bit of theory for today. So we have core growth, we have adjacency growth. The best strategy is when those are combined where you balance focus on the core. with focus and adaptation of the core with some degree of adjacency, but doesn’t cause you to lose focus. Six types of adjacency moves. Okay, then we get to the question of how do you make sure, what is the probability of success of an adjacency move? Because this is what gets companies into trouble all the time. And Chris has laid out three factors that seem to… drive success or failure, or let’s say are tied to success or failure in adjacency moves. I’ll put these in the show notes. I think this is pretty great. He said basically like three things. Is this going to succeed or not? First of all, before you even look at these, you got to sort of think about what is the boundary of my core? What is the boundary of the adjacency? You kind of have to define what you’re talking about. And in some markets that’s quite easy. We know what the core business of Starbucks is and we can say we’re going to China. That’s a clear adjacency market opportunity. Very simple. Okay, when we start talking about Alibaba doing e-commerce, well, that’s a bit fuzzy as a core. Does it include products and services? Does it include groceries? Does it include fashion? And when we move into entertainment, which they did, media, video. Okay, that’s an adjacency market. Do we really know what the boundary of that is either? So sometimes it can get kind of fuzzy that can get people into trouble. You wanna kind of define those as clearly as you can, which is sometimes not possible. Okay, once we get it, then we’ve got to assess it like a military campaign. Is this gonna work? We need to be very tactical. We’re gonna invade this neighboring country. Are we gonna get killed off? Are we gonna lose? Is it easy? Is it big? Is it worth the opportunity? And they kind of point to three factors. Number one, is the adjacency opportunity tightly tied to the core? Is it tightly tied to a strong core? Not just a weak core, a strong one. Is there a very short economic distance between the adjacency we’re going after and a strong core business we already have? How much does it overlap? Is it the same customers? Is it a direct extension of our current, let’s say we’re really good at a channel. We have very strong channel power, like we’ve got retail outlets everywhere. If we sell a second product, which would be an adjacency expansion within our core channel, There’s a lot of overlap there. Okay, let’s say we’re incredibly strong with one customer segment like middle-aged white dudes who buy Harley-Davidson’s in the US, which is their core market. That’s pretty much what they have as a business. Can we sell this group, I don’t know, jackets and lifestyle products as opposed to motorcycles? Okay, the economic distance between a relatively strong core and this adjacency is quite small. That’s what we want, a very tightly tied linkage. And it needs to be to a strong core, not a weak one. This is actually one of the areas where companies get into trouble all the time. Snapple says they wanna go into Gatorade. This is an example from one of the books. It sort of makes sense, hey, we’re Snapple, we sell beverages, let’s get into Gatorade. Turns out it wasn’t a good adjacency move. It turns out the production of making Snapple and Gatorade were totally different. Turns out the customers and advertising were pretty different. The points of purchase and the distribution were pretty different. It’s kind of one of those famous ones that didn’t work out, but that’s kind of number one factor. Tight, a tightly, what do I have problems saying this? It is tightly tied to a strong core. That’s factor number one. Factor number two. The adjacency itself is very attractive in terms of its profit pools. Now I’ve sort of talked about this as unit economics are attractive and the growth and the market size, the total addressable market are attractive. Okay, they just say, look, what are the profit pools in this business? Are we invading an attractive space? Now when Garena made their big jump into Shopee, That was actually an incredibly attractive space to go after. In fact, it may have been one of the single most attractive markets to go after, because e-commerce in Southeast Asia is awesome and marketplace platforms are well proven to have very good economics and competitive defensibility. So are you gonna invade somewhere that’s really attractive? That’s factor number two. Factor number three, last one. What is your ability to capture economic leadership of that market? Can you dominate that space? Are you gonna go into that space like Shopee and build up a platform business model with a really strong competitive power and really good profitability such that if we win, we’re gonna dominate and two, the space we’re invading didn’t have a competitor that was really powerful at that time. You know, are we gonna invade this space and then get pounded? Hey, we’re Lazada and Shopee. Let’s go into physical retail against Tesco and Walmart. Dude, that is a very strong incumbent. You know, good luck with that. Yes, it may be an attractive space, factor number two, but there is a dominant incumbent in there. The chances of us going in there and achieving sort of economic leadership is very small. So we talk a lot about competitive advantages, but competitive advantages are different if you’re an incumbent versus an attacker. So can we attack that space and win? Now, I talked about this a couple years ago when Mei Tuan said, we’re gonna jump into ride sharing, which they’ve sort of flirted with this idea, and they did a trial in Shanghai. And I kinda came out immediately and said, this is a terrible idea. because if you want to jump into ride sharing, okay, there’s reasons to do that. One, I don’t think it’s that attractive of a space. But if you’re gonna do it, dude, don’t go into Shanghai because that is directly going after Didi’s core. And Didi’s gonna come at you with everything they have because they live or die in ride sharing in the major cities of China. You are inviting a massive competitive response. You’re better off going to some tiny ancillary market like I don’t know, Kunming and doing ride sharing at airports. Go for some tiny peripheral market to start with. But this is going right at their core. They’re gonna come back at you with everything they have, which they did and basically Meituan retreated from that move fairly quickly. Anyway, so those are the three factors. Is this adjacency opportunity tightly tied to a strong core? Is the adjacency market attractive in terms of its profit pools, its growth, its potential, you know, attractive unit economics? And three, what is your ability to capture economic leadership in that market, which is a competitive question, incumbent versus attacker. And that’s pretty much it. Last point on this. Sometimes when you move into adjacencies, not only does it add to your core, it tightly ties to your core. It can also transform your core. Repeated adjacency moves off a strong core can kind of create like this amoeba type business where it’s a mechanism of evolution. You know, if most good core businesses last about eight to 10 to 12 years, this is a mechanism to sort of consistently evolve and as maybe one of your cores is decaying, you’re moving into others, or maybe your adjacencies are transforming the course. It’s sort of a way to think about this, which I think is useful. Okay, that’s pretty much the points I wanted to go through for today. Now, if we look at applications to digital businesses, here’s my so what’s. Choosing the right core business. I’ve talked about this as unit economics versus growth potential versus competitive strength and defensibility, those are my three. You know, what’s an attractive digital core? I think you kind of know my opinion on this. E-commerce, marketplaces, payment platforms, I really like, I like search businesses. Some of the attention businesses like WeChat. Line, WhatsApp, even TikTok to some degree. I mean, you kind of know what digital businesses I’ve been assessing for a long time now, where I like it, where I don’t. Yeah, you wanna keep in mind that some digital businesses, which we could call strong cores, are gonna change faster than others. Anything based on capturing consumer attention. Hey, watch my videos on YouTube versus TikTok versus live streaming versus whatever. They do tend to change faster. The value chains do tend to get reshuffled a bit more quickly. This idea of customer micro segmentation of a way of growing your core, that’s personalization, customization. In a data-driven world, that is strategy number one, almost all the time. And then this idea I’ve talked about before, that industry barriers just tend to fall and move around quickly. That’s kind of point number one. When you start to look at adjacency moves for digital businesses, I generally put them into this category of moderate relentless expansions. versus big trees. Big trees is an Alibaba term. They talk about, you know, they’re always launching new businesses. But they put some of them as big trees, where like we plant a lot of trees. Some of them are small, some of them are medium. But every now and then we get a big tree. And I’ll put a slide in the show notes that they show in their investor presentations, where look, that’s how we got Tsai Niao. That’s how we got Alibaba Cloud. These are major new businesses. not just this sort of moderate, relentless expansion into adjacencies, which they do all the time, into media, into hotels, into travel bookings, into all of this stuff, into food delivery. Every now and then, out of that process comes a major big tree. And they talk very openly about what the big ones are, and the ones they’ve pointed to in the last year are basically cloud logistics. Tsai Niao and Alibaba Cloud are the big ones. But you could also look at companies that struggle in this regard, like Baidu has been struggling with adjacencies for a long, long time. They’ve moved into business after, their core is search. That’s always been their search business. They haven’t grown it terribly well, which I think is a lack of focus. I don’t think it’s because it’s not possible. They’ve moved into adjacency after adjacency that has ended up being sort of a failure. or they had to sell it, they moved into food delivery, they moved into business services, now they’re going into cars. I wish they literally, by do which I’ve written about, I wish they would just say, look, we do search and we do cloud, that’s all we do. One core, one adjacency. I’d be quite happy if they would say that. But they don’t care about what I think. Company like Shopee. appears to be pretty good at major adjacencies from time to time, but they’re mostly growing their core. But they’ve got a couple big trees. Last point on this is when you think about going into adjacencies, if you’re a network based business model, if you’re a platform based business model, if you move into an adjacency in terms of a network, it can add value to everyone. When WeChat adds mini programs, we could call that an adjacency moved based on adding a new platform business model to the existing platform business model. Everything helps each other. These businesses, not only are they good opportunities for growth, but network adjacencies can really transform and be complementary to the core. If you add mini programs to WeChat, both the mini programs platform and the WeChat platform get stronger. That’s kind of just the nature of a network-based business model. When Facebook bought Instagram, it didn’t just add another source of growth, which it did, it strengthened both businesses. It made it better for the users. So network adjacencies are a big deal. I don’t usually use that term, but that’s another way to think about it. Digital businesses, I think, are pretty good at killing off non-performing businesses pretty quick. Most, like Amazon is famous for this. They launch a bunch of businesses all the time. If they don’t grow, like they launched a smartphone, right? Amazon built a smartphone. They killed that thing pretty fast. It wasn’t working, bam, we’re done. Jeff Bezos is famous for killing off, experimenting and killing off things very quickly. The other end of the spectrum would be Xiaomi. Xiaomi, I think they choose bad businesses to go into and they don’t kill them, they stay in them. Like smartphones, like I don’t know why they went into smartphones in 2010, 2011. It’s a very difficult business. You know, other businesses would have killed that off, like Jeff Bezos, but Xiaomi, they stayed in it for 10 years. You know, they just don’t seem to exit these things. DD is kind of interesting. They don’t seem to move into adjacencies very aggressively. They’ve always sort of said, we’re a mobility company. I’ve always thought that’s kind of strange. Meituan is an opposite example. They will jump from business to business like it’s nothing. Very good at that. Let’s see, complementary business models, last point. You know, if you look at my tower, the top of the tower I’ve put businesses I consider competitive fortresses. These are the businesses I most like. On that short list, there’s only about six things. One of them is complementary platforms. When you’ve got one platform business model, and then you add a second or a third and they complement each other. Those are adjacency moves that strengthen each other. That’s kind of like literally my favorite business model, which is why this company I gave you the heads up about last week, they’re building complementary platforms, three of them and maybe more. That’s why it got my attention. That’s why Shopee and Garena got my attention. That’s why Alibaba, I like complementary platform business models. Anyways, okay. That is pretty much what I wanted to go through. That was a healthy doethis of a theory for today. Let me leave you with a quote. This is from Chris Zuck, and it’s just from the book. I thought this was a great quote sort of summarizing a lot of this. So direct quote, mastery at the customer level and control over competitive dynamics are the keys to earning profits in business. Focused companies that have a strong or dominant core and that hit on a repeated formula for extending their strength to new arenas are the breeder reactors of business. That’s a good quote, I’ll read that again. Focused companies that have a strong, sorry, focused companies that have a strong or dominant core and that hit on a repeatable formula for extending their strength to new arenas. are the breeder reactors of business. These companies create value year after year while the majority of businesses live in a twilight of uncertainty, feeling more controlled by outsized forces than by their own will.” Dude, that’s a good quote. I’ll put that in the show notes as well. I think that captured a lot of it. He talks a lot about repeatability as a way to do this because if you repeat, you repeat, you repeat at doing this sort of strategy, you get better at it. And it was, okay, so that is basically the theory for today. That was a lot. The two core concepts for today, growth, core versus adjacency, and digital operating basics, which is where a lot of this stuff sits. If you look at my tower, this, almost all of this goes under. digital operating basics which is level number five of the tower midway down the bottom. Okay. As for me, I’m back in home in Bangkok which is awesome. I finished up my quarantine in Phuket which is really not quarantine, it’s just sort of a mandatory seven day vacation. That was fun and I had a good time but I’m kinda happy to be home. Just sort of fixing things up here and. The country is basically open now, which is great, because it was getting kind of boring when you couldn’t go anywhere or do anything. So it’s pretty great. I’m not really planning on going anywhere, at least for the next six weeks. So I’m gonna sort of stay at home and fix things up. Yeah, it’s gonna be nice. I’m trying to get out of the country probably end of November, December, which is when the pollution starts. When I moved here from Beijing, one of the thoughts I had was like, because I was kind of tired of the pollution of. Beijing, like you had to wear a mask all the time. This is before COVID and just for pollution reasons. So I’ll move to Bangkok. And I didn’t know there was pollution here in the couple months a year, like January, February, because I guess people burn their crops or something in the North and it all blows here. So I’m gonna try and bug out of the country in December and maybe go to the Mediterranean. But anyways, that’s kind of, other than that, I’ll sort of hang out here. Let’s see, any recommendations? Oh. On the way home from Phuket, I turned on Netflix, and the top trending thing on Netflix was this TV show called Squid Game. New series, I guess, not TV show. Man, that killed my trip. Like, if you haven’t watched this series, Squid Game, wow, I mean, it’s really violent. I mean, it is a violent, violent TV show about, not giving anything away here, but it’s basically about adults. who end up having to play kid games, like they played in elementary school, like red light, green light. But the consequences are death. So they’re playing red light, green light, and everyone’s dying left and right. It’s really just a sick premise, but it’s some awesome TV. Go watch the first episode. Like, man, anyways, that killed my trip home. I watched the first episode. I’ve been watching that whole show. Boy, that is not, you can find people talking about it all over the place. That is not an underestimated show. It deserves the reputation it has. Anyway, Squid Game, go check that one out, if that’s your kind of thing. If violence is not your thing, don’t check it out. Anyways, that was my discovery for the weekend. Okay, I think that’s enough, kind of a lot of theory today. I hope that’s helpful. This is the kind of material. where I think you really need several passes to get it. Nobody’s gonna get that on the first pass. This is one of these ideas where it takes you, I mean it took me years to sort of ingrain that stuff because I’d read it and I’d read it again, I’d thought about it and then it becomes second nature but if you feel a little bit maybe overwhelmed by this, that’s totally normal, that’s a lot of thinking. And I generally, it requires me to take two or three passes of stuff like that before I really start to internalize it. Anyways. Okay, I hope that’s helpful. Hope everyone’s doing well, and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.