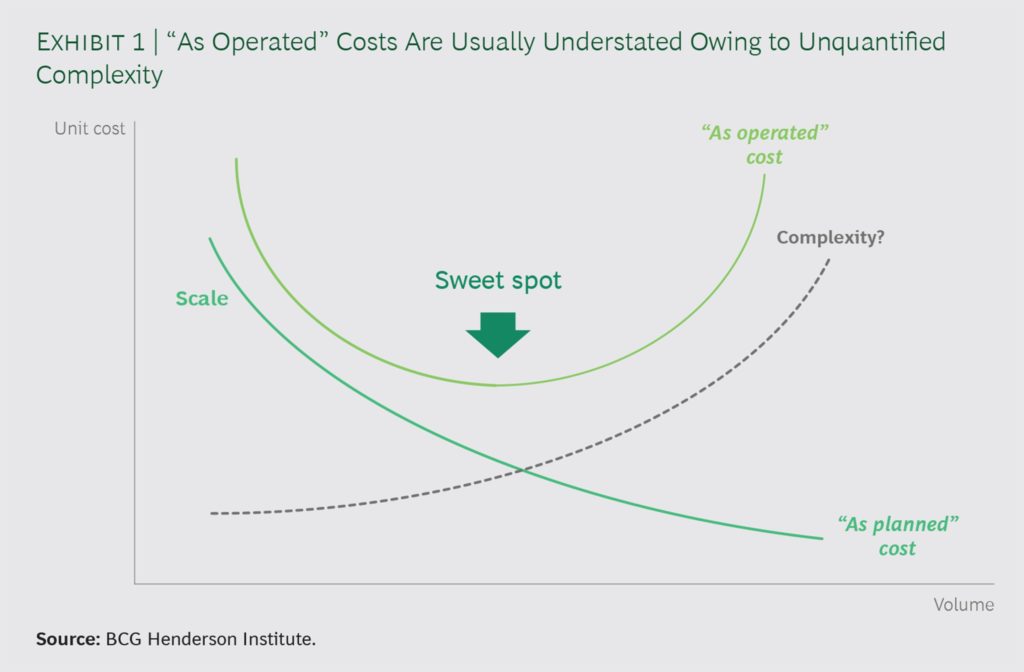

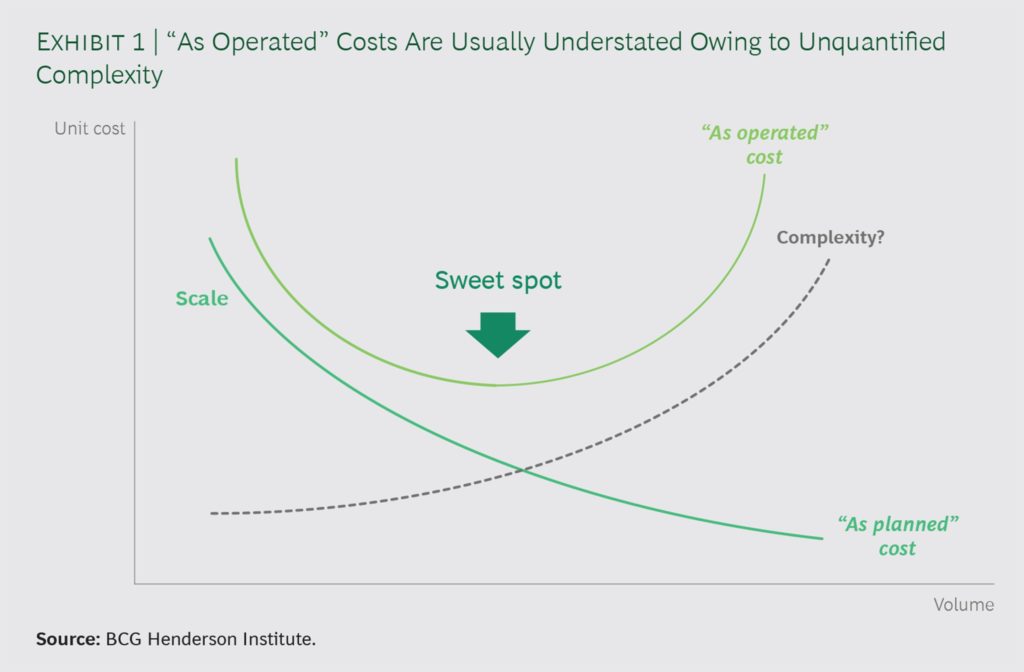

There was a good paper recently published by Martin Reeves and Raj Varadajaran of the Boston Consulting Group. The paper (When Resilience Is More Important Than Efficiency) touched on a lot of issues related to digital competition – but there was one chart that I thought really hit at the center of a lot of the big digital stuff happening – which is below.

This chart could almost be a summary of the industrial age – and of how you win on the supply-side in a mostly physical world. I’ll explain this comment shortly.

This is the kind of chart you usually see in a description of economies of scale (something actually discussed a lot by BCG founder Bruce Henderson). And you often see this chart when discussing mass production. Basically, there is a downward sloping dark green line that shows that certain fixed costs decrease with unit volume. So a factory that operates with mostly fixed costs is cheaper on a per unit basis than a competitor with smaller volume. And an express delivery company like Fedex will be cheaper per package because it is much a greater volume through its network (which has a lot of fixed costs). Per unit cost is the fixed cost divided by the volume.

I have talk a lot about economies of scale as a type of supply-side competitive advantage that depends on you being significantly larger than your competitor. This can make you cheaper in fixed costs like manufacturing and distribution. And it can enable you to outspend them in fixed costs like marketing and R&D. But the advantage only exists when you are larger in scale. When Pepsi finally caught Coca-Cola in size, Coke discovered it could no longer outspend them on marketing (and in getting shelf space).

However, there are actually two additional points to this that matter.

The first, as shown on the chart, is the light green light going up to the right. The point is that a scale advantage only works in practice to a certain size. Because with scale, other costs start to emerge (like complexity) and the net cost per unit starts to rise again. This is why advantages based on economies of scale don’t lead to winner-take-all markets. Company with big scale advantages (like Coca-Cola and Budweiser) can be become big but they don’t end up with 100% of the market. Trees don’t grow to the sky and economies of scale only work for a while.

The second point is that this advantage also requires a circumscribed market. It’s not enough to just be bigger than your competitor. The market has to be limited so there isn’t enough room for competitors to match you in scale. Nebraska Furniture Mart (a Buffett company) dominates the Omaha furniture market. And since people don’t ship furniture that far, the market is limited by geography. No other company has enough room to get to their scale. And they have dominated for decades. This is one of the problems with being a global manufacturer (say in motorcycles). There is always room for another company to get to scale.

So back to the main point. Why do these other costs start to increase with scale?

“As Operated Costs” Increase With Inter-Connectivity. And With Supply / Demand Volatility.

The BCG paper cites a couple of factors that lead to what they call the difference between “as planned cost” and “as operated cost”.

“…we know that complexity grows as systems become larger and more connected, and that when that happens hidden costs generally soar beyond costs that can be explicitly planned.”

“In our example, delayed pilots, flight attendants, or planes each had the potential to trigger a chain of delays throughout the system. (See Exhibit 1.) To be prepared to counter these cascades, the airline maintained extra resources (spare planes, reserve pilots and flight attendants, extra gate agents and maintenance staff, spare gates, and so forth). Delay-inducing perturbations were seen as exogenous, uncontrollable factors, and the spare resources were regarded as just a “cost of doing business.” Removing the buffers would have reduced planned costs and thereby increased efficiency—but it also would have amplified interdependence and fragility and ultimately made matters worse.”

The point of their paper is that companies need to manage for resiliency instead of just efficiency. That when there are interconnections in a business (like flight schedules) and / or volatility in supply and demand, a more system-wide approach to costs needs to be used. It is an increase in complexity with scale.

That’s an interesting point but I think it misses the much bigger one, which is that there are a list of disadvantages with scale, scope, complexity and connectivity. And that these are inherent to organizations operated by human beings. But in a digital age, we are starting to see operations run without any human beings. And they don’t appear to be limited in these ways. More on that in Part 2.

But first, more on why operations become costly and problem with size.

The Disadvantages of Scale, Scope, Complexity and Connectivity

Economies of scale (the dark green line on the graphic) get better with volume. But there are actually quite a lot of problems and costs that increase as well. BCG’s comments about inter-connectivity and volatility are two. Here are some others.

Vulnerable to Specialists

As you get bigger, you naturally target a bigger audience. So instead of publishing a magazine for a small niche, like tourists who love Thai food, you publish a magazine for all food lovers. You need a bigger market to support your bigger organization and that almost always means going broader in most products and services. And that leaves you vulnerable to competitors that specialize.

Daily newspapers are a great example of this. Metropolitan newspapers used to serve the entire local community. The Boston Globe was for everyone in Boston. The Buffalo News (another Buffett company) was for everyone in Buffalo. And specialized internet and media companies just took these companies apart section by section. TripAdvisor took the travel section. Ebay and Craigslist took the classifieds. Buzzfeed took, well, I don’t know what (politics?). Media companies going for scale got sliced up by specialist plays. It was brutal.

Big, Dumb Bureaucracies

Charlie Munger talks alot about how bureaucracy inevitably increases with scale, even without increased complexity or scope. The more human beings you put together in an organization, the more bureaucracy, self-interest and dysfunction you get. Division heads create their own little fiefdoms. Money gets spend less wisely. Communication becomes harder, with more messages about more topics. Internal politics gets worse.

Human beings are just not very good at organizing beyond a certain size. From Munger:

“They also tend to become somewhat corrupt. In other words, if I’ve got a department and you’ve got a department and we kind of share power running this thing, there’s sort of an unwritten rule: “If you won’t bother me, I won’t bother you and we’re both happy.” So you get layers of management and associated costs that nobody needs. Then, while people are justifying all these layers, it takes forever to get anything done. They’re too slow to make decisions and nimbler people run circles around them.”

“The constant curse of scale is that it leads to big, dumb bureaucracy—which, of course, reaches its highest and worst form in government where the incentives are really awful. That doesn’t mean we don’t need governments—because we do. But it’s a terrible problem to get big bureaucracies to behave.”

He also talks about how franchises like Subway and McDonald’s are pretty clever solutions to this problem. By being operated by local owners, you get the benefits of scale (centralized purchasing, big marketing spend) but the operations are small and local.

Unwieldy Operational Scope

My aunt buys GE stock. She always follows the news and sometimes asks me what I think of whatever happened that week. And my answer is always the same, I don’t know how to value GE. It’s got too many products. It’s in too many businesses. It’s got all sorts division like healthcare equipment and financing. The scope of its products and services is too large. I can’t figure it out. How can anyone possible run that company? Who can understand all those products and their markets? And all the supporting operations?

I think human beings can understand a handful of products. And we can manage the operations to a certain level of complexity. But there are no companies that can design, manufacture and sell 50,000 different products a year. That scope is beyond our abilities. So Coca-Cola doesn’t sell 1,000 different brands of soda. And they certainly don’t sell soda, washing machines and electronics.

Complexity

This is a more generalized version of the problems of scope. As businesses grow in products, operations and geography, they just become more and more complex. Even the most successful global companies offer a fairly simple line of products, like Nestle or Pepsi. Or they stay specialized functionally, like in engine management systems. And even then, they struggle with the supply chains and operations.

When I ask JD and Alibaba where they are focusing their AI efforts, they both answer the same thing: logistics. Because they have both built national logistics networks that support the daily purchases of a billion people on a minute-by-minute basis. And the operations of the logistics network and its massive inventory is beyond what anyone can now understand. The AI can do it. But humans can’t. We have a limit individually and as a group when it comes to operational complexity.

***

Which brings us back to the main chart.

So many of the factors creating the increasing “as operated costs” in the light green line are about human beings, their capabilities and their ability to organize. But what if you were to build a company that was completely run by software and humans were only involved in the design and oversight? Could you remove the light green line? And our limits on our ability to increase in scale, scope, complexity and connectivity?

In Part 2, I will discuss zero-human operations (also called AI factories) and why they be the holy grail of the digital age.

Thanks for reading – jeff

How Ant Financial / Alipay is Building an AI Factory in Financial Services (pt 2 of 2)

——-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.