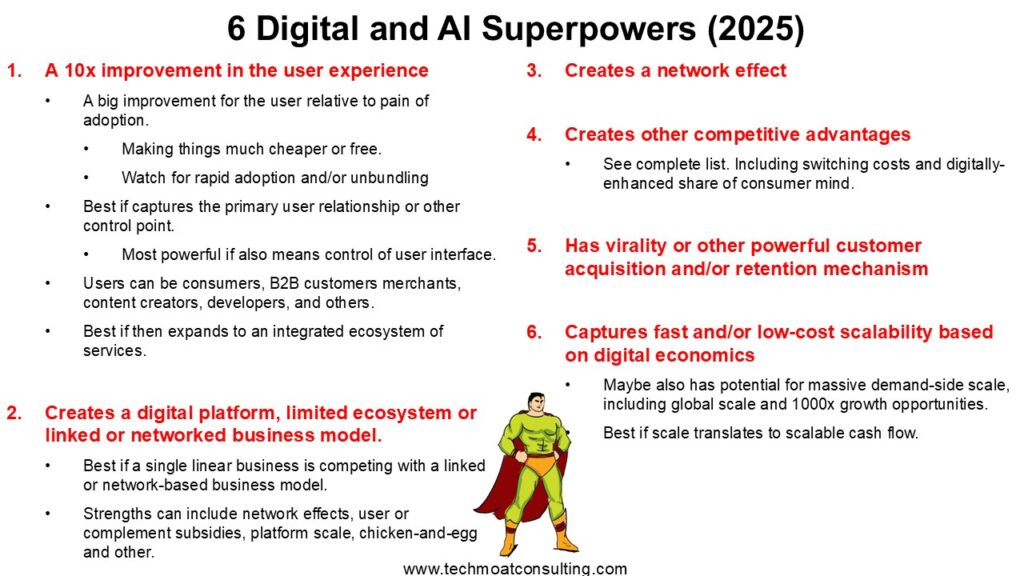

I keep a list of Digital Superpowers that I update every year. This is my cheat sheet for identifying particularly powerful businesses. Most of the digital giants have 3-4 of these superpowers.

You can read more about them here.

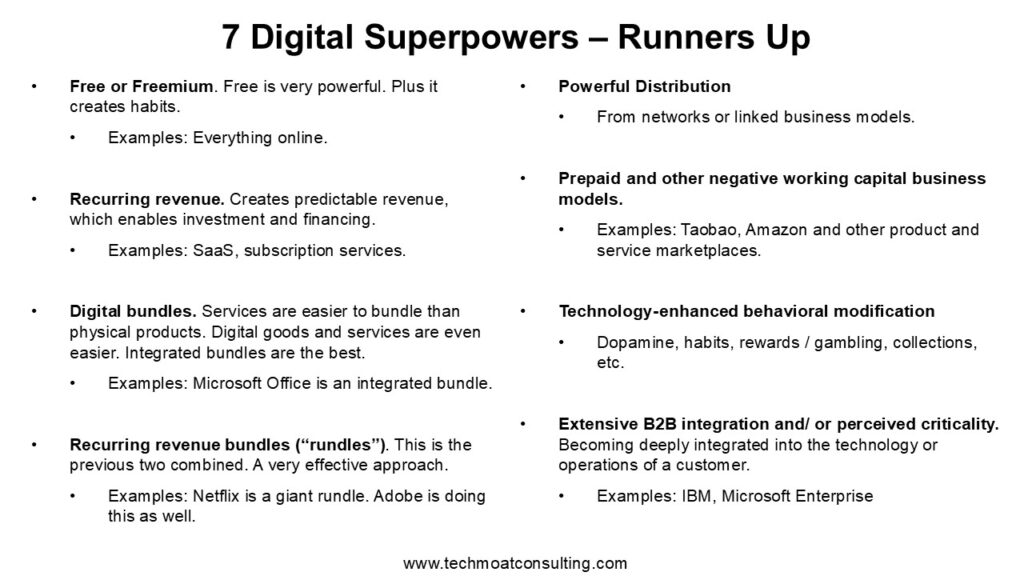

I also have a runners-up list with other powerful attributes. These didn’t quite make the superpowers list.

And I also think about a kryptonite list. A list of anti-superpowers. These are the attributes you really don’t want in your business (if you can avoid them).

But it’s actually harder to make a list of bad stuff.

Because there an endless list of things that can make a business bad. Corrupt management. Unattractive unit economics. Excessive regulation. Obsolete products. This list can go on forever.

And you really have to start by looking at unattractive industries. All analysts look at:

- Industry structure

- Firm specific characteristics

Competition guru Michael Porter wrote a lot about two unattractive industry types.

- Fragmented industries

- International industries

These industries (and others) just have way too much competition. And they can have particularly ferocious competition. They are pretty unattractive overall.

Lots of competitors almost guarantees margins are going to be small to horrible. Even for businesses with good products, good management and good regulations. You can do everything right. But if you are in an unattractive industry, life is going to be hard.

Porter is still the standard for classical strategy. You can use his frameworks to map out the industry structure and its value chains. Then you can identify the attractive positions. And your strategy is to capture one of those positions and get to scale.

He is less well-known for his analysis of fragmented and other unattractive industries. He talks about this a lot in his book Competitive Advantage. Most of the thinking in this article is from that book.

–

Which brings me to the key question.

Why Are Some Industries Unattractive? What Makes This Happen?

I spend a lot of time looking at the giants. The international giants like Google. The national giants like Walmart. And even the regional giants like See’s Candies.

I am looking for competitive dominance. That is almost always a prerequisite to economic profits.

But lots of industries and businesses, like restaurants and dental practices, are overwhelmingly small and fragmented. Nobody ever gets to significant large market share. Let alone dominance.

In fact, dominating the market seems not possible. And this is often true. Dominance is not possible. And, going for scale and/or dominance in a fragmented industry is usually a strategic mistake.

Porter’s approach for these types of industries is to assess the degree of rivalry.

- How many players are in this particular business?

- How ferociously do they compete?

Both of those factors matter.

The number of competitors is usually tied to barriers to entry. If barriers are low, the more enter the business. That means a higher degree of competition. Which leads to lower margins and a tougher environment.

Ferocity is a bit more complicated. You can have the same number of competitors in two industries. But in one they are fighting ferociously (price wars, etc.) and in the other they are sort of friendly and cooperative. It’s competition vs. cooperation. Charlie Munger once said he looked at this question and couldn’t figure out why one industry was ferocious and one congeal.

Here’s how I view it.

There are other factors of course. But the amount and degree of competition is a good metric to identify an unattractive industry.

In his book, Michael Porter mentioned 9 characteristics of unattractive businesses:

1. There are a large number of competitors.

As mentioned, when there are more competitors, they tend to compete more. And it makes cooperation (which is the opposite of competition) more difficult. When firms cooperate (which can be illegal at a certain point), margins usually increase for everyone.

But when there are lots of firms, cooperation is unlikely to happen. First, there are too many companies doing too much. Cutting prices. Launching products. Too much information and misinformation are a problem.

Second, lots of companies means there are likely a few mavericks. Companies doing crazy things with their pricing and marketing.

In contrast, when an industry is concentrated in a few firms, there is less overall competition. And there is usually more understanding between parties. Cooperation is easier.

Note: International competition is arguably the worst scenario.

2. There are lots of equally balanced firms.

When some businesses are big and others are small, there tends to be more order. The giants coordinate and set the rules for others. Competition is generally less ferocious.

However, when there are lots rivals of about the same size, competition can really get heated. You see this all the time with SMEs. And with small Chinese manufacturers selling on Amazon.

3. There is slow growth.

Rapid growth means lots of competitors have room to win. You can grow your revenue without taking customers from others.

However, with slow or stagnant growth, you can only take from others. Slowing growth is when everyone turns their guns on each other. It’s pretty brutal. That’s when you find out who has a competitive advantage and who doesn’t.

4. There are high fixed costs relative to value.

When a business has high fixed costs relative to value (revenue), it means its margins are very dependent on maintaining volume. If volume drops, you can move into the red very quickly. That doesn’t happen if its mostly variable costs.

High fixed cost businesses need to keep the volume of sales moving. That can make competition pretty fierce. When volume drops, they are prone to dropping price to keep the volume going.

5. There is a lack of differentiation, which is even worse with no switching costs.

Competition in commodity products is mostly about price. You just don’t other features to compete on. A lack of differentiation can be brutal.

And this gets even worse when there are no switching costs. When customers can switch easily between the undifferentiated products.

6. Capacity is in large increments.

In some businesses, it’s hard to scale up and down production capacity in small amounts. You have to build an entirely new factory and launch a new oil platform. This is the part of economies of scale people don’t talk about. It’s not just superior scale. How that scale increases and decreases can have a big impact.

In businesses where capacity can only increase / decrease in large increments, you often see periods of over-capacity and then periods of undercapacity. This can wreak havoc with pricing. We see this often in the energy business. When oil prices are high, everyone makes the big investments to build capacity (new oil platforms). This usually leads to over-capacity. And then when oil prices drop, you get aggressive price cuts. Investors like Warren Buffet are good at buying energy businesses in the down years.

7. There are lots of diverse competitors, strategies and goals.

Diversity in products is good for healthy competition and margins. As mentioned, you don’t want undifferentiated products.

But diversity in business types and strategies can be bad.

For example, a business unit within a larger business will act very differently than a stand-alone player. Similarly, SMEs and small family businesses with owner / managers act differently than public companies.

This type of diversity in business type means different strategies and goals. It makes the market complicated. And often makes cooperation impossible. This is one of the reasons foreign businesses can be so difficult to deal with. They usually have completely different circumstances and objectives than domestic players.

8. The strategic stakes are high.

This is similar to the last point.

Sometimes certain players will see a market as a strategic “must win”. They will sacrifice almost anything to win this market. Which makes competing with them particularly brutal.

We see this right now with Chinese firms entering Southeast Asia. They view it as a strategic imperative. Their domestic market has lower growth (and political risk). The US and Europe are questionable because of political actions. So, Asia is their must win market.

We also see this in China with Didi vs. Meituan. Meituan enters ride sharing from time to time. And Didi goes 100% to push them out. Ride-sharing in China is optional for Meituan but is “must win” for Didi.

9. There are high exit barriers.

Last one. And this is important.

In an economically rational market, businesses will enter an attractive market (high ROIC, good growth) when it is above their cost of capital or opportunity cost. And businesses will keep entering until the opportunity is no longer attractive.

Similarly, economically rational businesses will exit an unattractive market. When the ROIC is lower than the cost of capital. And the exiting firms should reduce excessive and/or irrational levels of competition.

That’s the theory.

But sometimes, firms don’t exit markets when they economically should. There can be high exit barriers – which can be economic, strategic and/or emotional. Which make businesses stay in a market longer than they should. And they might accept neutral and even negative returns. This can make a market particularly brutal and unattractive.

This last point is important. Porter talks a lot about exit barriers.

What Creates High Barriers to Exit?

I talk a lot about entry barriers. That’s how you protect your business. I use this picture.

But people often assume high entry barriers means an attractive ROIC (relative to rivals). And that is not exactly true. To understand the degree of competition, you have to look at the rate of market entry minus the rate of market exit. That is what determines how competitive a space is.

Barriers to exit are important.

Michael Porters mentions several things that can create high exit barriers. I’ll run through these quickly.

- Specialized assets. Certain assets are just not worth much in other businesses. If you have land, you can use it for something else. But specialized machinery for manufacturing MRI machines has no other use. Specialized assets can have low liquidation value, can be hard to transfer to someone else, and can be hard to convert to another use. This raises the barrier to exit.

- Fixed costs for exit. Sometimes you get a big financial hit when you exit a business. Such as when you have expensive labor agreements and/or big resettlement costs. And sometimes you need to keep offering certain capabilities even after you have exited, such as supplying spare parts or maintenance services for previously sold products.

- Strategic value to the firm or to another biz unit. I see this a lot. You see a business operating in difficult area (like content creation) because it is valuable to another business (like ecommerce). So, they stay in the business because of its strategic value elsewhere.

- Emotion overrides economic logic. Senior managers don’t like to close down their own businesses and put themselves out of work. Especially after they have spent their careers rising to the top positions. In these cases, you need someone like Warren Buffett to buy the business (like Berkshire Hathaway) and force the exit. Carl Icahn frequently targets such management situations. Pride can also override economic logic. 3G capital likes to buy companies run by the children of the founders. They often have little ability but too much pride to step aside. Another factor can be loyalty to employees. Company towns will keep operating long after the business no longer makes sense (Carl Icahn likes these situations too). And finally, there can be a romantic appeal to the business (Hollywood actors, YouTubers). And they stay involved when they should leave.

- Government or social restrictions. Last point. Sometimes you’re not allowed to close a business. Or not without a major penalty. Or not if it is socially unacceptable. Japanese businesses have serious social obligations to their employees.

Final Question: What Sparks Ferocious Competition?

As mentioned, a greater number of firms generally means more intense competition. To get a cooperative situation, you need a smaller number of firms (i.e., concentration). And it helps if they are homogenous. Or if it is a situation with a few giants and a lot of dwarves. Larger players can get alone with each other and impose order on everyone else.

But even with these situations, we can still see some industries with real competitive ferocity.

As mentioned, Charlie Munger said he had looked at this question and couldn’t figure it out. Some oligopolies are quite peaceful (Coke vs. Pepsi, branded cereals). Others are crazy (pretty much everything in China).

Michael Porter mentions several factors that can promote peace vs ferocious competition.

Some good factors are:

- Firms have a long history of working together. This builds trust and makes continued cooperation easier.

- When there are multiple bargaining arenas. When the market can be segmented easily, you can avoid each other. Auction house giants Christie’s and Sotheby (which got in trouble for too much cooperation) tend to segment into different types of art. This can also be done geographically. And by customer type. Having multiple arenas enables easier cooperation (i.e., bargaining).

- When everyone is profitable. Nobody is in a desperate financial situation.

- When there is high growth. As mentioned, there is room to avoid stealing customers from each other.

Bad factors are listed throughout this article. But three to really keep in mind are:

- Variability in demand. When the amount and / or type of products purchased changes frequently, it just makes things more unpredictable. It makes it harder to coordinate.

- High fixed costs. As mentioned, this can result in price cuts and frequent desperation.

- Flat growth or declining growth.

***

That’s my summary of the characteristics of unattractive industries (in terms of competition).

And this tees up Part 2, which is about fragmented industries. It’s a fascinating topic. Not only do fragmented industries have lots of players (bad), they are also situations where consolidation (and dominance) is not even possible. I’ll cover that in Part 2.

Cheers, Jeff

———

Related articles:

- Frameworks and Strategies for Fragmented Industries (2 of 2) (Tech Strategy)

- 5 Misconceptions About Barriers to Entry (Tech Strategy)

- The Big Strategy Concepts for Web 3 (1 of 3) (Tech Strategy – Daily Article)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Barriers to Entry

- Barriers to Exit

- Industry Structure: Overly Competitive Industries

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

———–

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.