This week’s podcast is about Skillz and Electronic Arts. There are some interesting and evolving strategy aspects to gaming – especially as it goes to multiplayer and tournaments. And as Skillz opens up tournament gaming based on cash rewards, the question is how far into gambling is this going to go?

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

The book I mentioned was Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas

—–—

Related articles:

- Ant Financial and the 3 Types of Network Effects (Asia Tech Strategy – Podcast 86)

- A Day in the Life of a Didi Chuxing Driver (Pt 1 of 3)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Network Effects

- Share of the Consumer Mind

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Skillz

- Electronic Arts

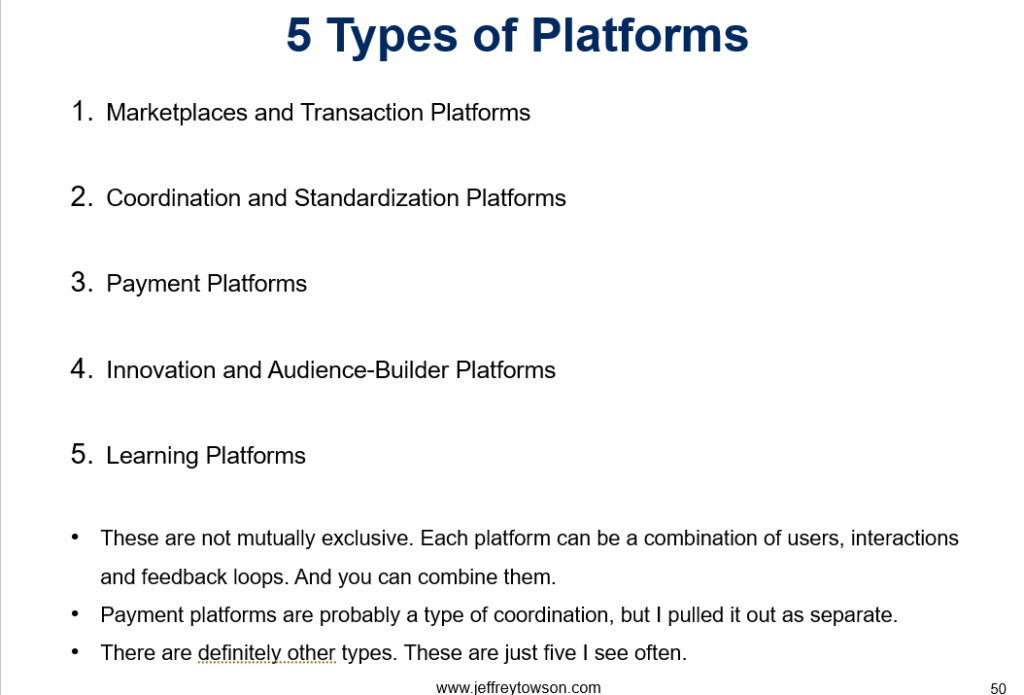

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, skills versus electronic arts, the emergence of digital sin stocks. Now, I guess these are both US companies so neither of them are Asia Tech Strategy, but I mean they’re good examples of gaming and gaming is kind of an Asia thing so I don’t know, there you go. And we had a group in Bangkok in the last couple of days do a presentation on skills, very well done. Really thinking is just getting better and better. So I thought I’d sort of build on that and compare it to Electronic Arts, which is also pretty interesting company. The whole gaming space is pretty fantastic. I mean, it’s really the frontier of pretty much everything on sort of consumer engagement. everything from points to loyalty to leveling up to keeping retention. I mean the gaming companies have been focused on the user experience like nobody else for decades and they keep pioneering stuff that we then see sort of move into other areas like e-commerce. But gaming is really the frontier in many ways so I thought it would be a good example of that. So that’s what I’m going to talk about. Now for those of you who are subscribers I think we’re going to move on to some new companies this week. I kind of ran out of things to talk about, DeeDee. It wasn’t nearly as complicated as I thought it was going to be. And I’ve been sending you stuff based on theories, some competitive advantage frameworks, probably three or four of them in the last two weeks, economies of scale, variable cost advantages, things like that, network effects. I’ll send you a bit of a summary today to sort of pull all that together into one graphic, almost a checklist so you can sort of run down the list. Here’s the competitive advantages we’re looking at. Do they exist or not? So I’ll do that in the next day. But yeah, we’ll probably move on to some new stuff. And let’s see, standard disclaimer. Nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may be incorrect or no longer relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Now. The concepts for today, which are always in the concept library on the web page, we’re going to talk mostly about network effects and share of the consumer mind, which are two demand side competitive advantages. These are areas where you can build strength against your competitors in terms of revenue or demand. People often consider it like a pricing thing. Oh, you can charge 15%… percent more because you’re Coke or whatever. Therefore you have some sort of demand side advantage. Often it doesn’t show up in pricing, it shows up in repeat purchases. So it can be revenue or you could sort of describe it as demand. There’s ways to build fairly good competitive advantages that get people coming back to your site over and over, even for free stuff. And then maybe you monetize part of it later. So. I would make that, I would say sort of revenue and demand side advantages, because they’re not always the same thing. Usually people just say, oh, it’s pricing power. No, there’s more to it than that. But those are the two ideas. You can go to the concept library on the webpage, click on network effects, click on share of the consumer mind. But I’ll dig into those, because these are both like, I mean, these are the big guns of gaming. There’s a lot of other stuff going on, but these are the big, big guns of this whole sector. So I’ll sort of go into that. So let me start with Electronic Arts, because this is kind of a, I mean, this is an old company, right? It’s been around forever, based in Redwood City, California. This is the early days of Silicon Valley. A lot of these gaming companies, when you’re talking about the late 1970s, 1980s and back in the days of Donkey Kong and Atari and all that stuff, they’ve been around for a long, long time. This is one of the older ones and… It’s a, let’s say it’s a more traditional business model that has evolved over time, but it’s not a radical departure. It’s more like a gradual evolution. Okay, but they’ve been public for a while. So you can go through their stuff. They’re listed on the NASDAQ and it’s interesting company here. You know how they describe themselves. Pretty standard. We develop, market, publish, and deliver games, content, and services. Now the first part is pretty standard. Develop, market, publish. Fine. Every book company does that every year. It’s that second bit. Games, content, and services. Now fifteen years ago that would have just said games. But they’ve expanded more into content and services going on for game consoles, PCs, mobile phones, and tablets. Okay, lots of types of distribution for global audiences. And that’s pretty standard for any of these sort of traditional game companies. And the first thing you’re going to see is you’re going to look at their game portfolio. You know, what popular games do you have? Where are you making most of your money? What do they have? So their intellectual property. I mean, it’s like if you’re looking at Disney, the first thing you look at is, okay, they got the Avengers. They got Iron Man. They got Mulan. Okay, so wholly owned IP. The Sims games. Need for Speed. Plants vs. Zombies, Battlefield, and then in addition to the Holy Own they have licensed games which means they’re going to Madden, NFL, Star Wars, right? They’re going to the entertainment companies and they’re licensing that. And they’ve got some of the big guns in terms of intellectual property and you can see that by just breaking it down by revenue. And that’s kind of arguably one of the defining characteristics of the whole space is look only want to play certain games this is almost entirely a blockbuster type of business. I mean it makes Hollywood look easy. At least in Hollywood you can make some bad films and they still make, you know, they make some money. You can make, you know, 30 or 50 TV show pilots a year and most of them sink and two of them do well and five just kind of linger on and do fine. Gaming it’s all or nothing. And it’s not just year after year, the same games go on for years and years and decades in some courts. So I mean it’s an extreme version of a blockbuster business on the developer side. Now if you are a successful developer that’s awesome because you have tremendous power globally. But the vast majority of people, you know that’s like saying, oh I own the Iron Man intellectual property. Well yeah that’s awesome but all the other cartoonists, you know they don’t have that. So it’s a… It’s a pretty sort of extreme example of blockbuster economics. And you see it all throughout the industry. Now they’re going to talk a lot about their World Cup stuff, their Ultimate Team. OK, but that’s sort of like the we develop, manufacture, market, publish, and deliver games. But then you move into the other. The content bit’s not as interesting. What’s interesting is when they say we do services. Because they’ll talk a lot about live services. And people use different words for this. Skills. the next company I’ll talk about, they use the term live ops. But it’s basically this idea of like, you know, we’re not just publishing a game and then people plug it into their console and play it at home. These are live events that require live support, whether it’s, I don’t know, running tournaments, payment services, social media, chatting, streaming. There’s a live operations component to this that can be fairly impressive. And then there’s a non-live component as well, payment mechanism, things like that. But that whole services bucket is kind of a big deal. I’ll talk about that more. Now, when Electronic Arts talks about their live services, basically it’s defined as revenue outside of the games, basically. They say it’s to enhance gameplay, but you get extra content, you do a subscription, you sign up. If you’re doing tournaments and sporting and eSports stuff, you can get access to better players, things like that. But when they talk about their World Cup thing, their Ultimate Team, it’s about 50% of the revenue in that one aspect. So in some of these games, especially the eSports stuff, it’s pretty significant, the whole live services, live ops, that sort of stuff. And as you go through their various games, you can see how they’re integrating this in. For Ultimate Team, okay. You can do competition, lots of self-improvement, things like that. Battlefront, you can sell maps and vehicles, things like that. But basically, I mean, it’s games plus live services. That’s what’s interesting, that’s what you’re gonna project forward, and then you wanna look at that globally, which gets you into the world of companies like NetEase and Tencent and Alibaba and big gaming competitions in Bangkok and all this crazy stuff. Okay. The other part I think that’s worth pointing out, I mean for those of you who know gaming, obviously I’m not telling you anything you don’t know, this is all pretty standard. But I’m going to tee up because I want to talk about skills in comparison. Significant relationships for Electronic Arts, these are kind of a big deal. Sony and Microsoft, why? Well, because they make the big console games, right? PlayStation, Xbox. And then they have an online aspect, they have their stores, other significant relationships, Apple, Google, app stores. another distribution channel obviously and then Tenzen. So I mean you have these major, let’s call it relationships, but they’re partners, they’re critical for distribution, but they’re also competitors. I mean they make games, they do distribution. So you have this funny intermingling between you know all the major players of distribution with the major players of content and they both try to dabble in each other’s world. I mean Garena has its own I mean, free fire. And okay, fine. You look at how are they competing together. It’s pretty simple. I mean, it’s not, obviously the game popularity is the big thing. And then you have changing distribution and you have changing business models. I mean, those are kind of the three buckets I look in all of this. And so you look at Activision, Take-Two, Epic Games, Sony, Tencent, NetEase, Microsoft, all of them. And one of the reasons I don’t follow this sector very much is because it’s always the same players. There aren’t enough companies to study. Like, it’s pretty much, I mean, if you’re a professional analyst in this sector, you’re kind of looking at the same big companies year after year. You look at how they change, but the field doesn’t change very much year after year. So that’s part of it. Okay, and then we go to risks. Risk is always my favorite section of any 10K. The biggest risk. you need obviously high quality successful games. And very few succeed in this and that generates most of your revenue and you gotta go for the blockbuster and hopefully it’s a blockbuster that becomes a franchise that goes on and on. And you know, that’s let’s say 51 at least or more part of the game. So they’re pretty dependent on this and under performance of any really even a single major title can have a pretty big. impact on this stuff. Catastrophic events, adverse events related to a game, if you have major problems within a game, that can be an issue. Timing can actually be a problem, especially these games that are tied to movies or sports events. You know, if they have the new movie coming out in six months, the game has to be ready. If you miss your window, you don’t get the bump. But if you rush it and you put out a garbage game, which a lot of these movie-based games really are not good, that’s bad. And then if there’s a problem with it because you rushed it, okay, that’s another problem. So it always struck me being a game developer as a pretty difficult business. Think about how that type of content is different than say a TikTok video. TikTok doesn’t have any of these problems. You know, people put up little videos and, you know, they can be good, bad, mediocre, and one, people will watch the good ones and the bad ones. They don’t just watch the great ones. And it’s a platform so they don’t have to do it. I mean, it’s just a much easier media business. This is kind of an extreme version. I think music is similar in that regard. I think music is very difficult. Nobody wants to listen to user-generated content. Like, hey, I’ve got a song, let me sing it for you. Nobody wants to hear that. That works fine for video and most of YouTube. Okay, last bit and then I’ll get to the point. The financials. Big surprise, the financials are beautiful. It’s a purely digital good. And if you’ve got one of the few successful ones, it’s a cash machine. I mean, the income statement is fantastic. I’ll give you a couple of numbers. It’s not growing dramatically. Revenue, 2020, $5.5 billion. That was up from 5 billion in 2019, which was actually down a little bit from 2018. So it’s kind of cruising around in that five plus billion dollar range. But then you look at the gross profit because it’s software and oh, big surprise, it’s 76, 78% gross profit, which is spectacular. They’re spending a ton of money on R&D, 28, 29, 30% of revenue goes into R&D, only about 10% on marketing and sales. Net result operating profit 25-26%. I mean that’s just, man if you can get that in life, it’s, I mean the people who own the Ironman IP have the same thing. If you’ve got valuable IP, you know, that can be a pretty nice life. It’s just hard to pull it off. Cash flow statement is equally awesome. And actually the balance sheet is pretty great too. One of the cool things, I don’t know if I’ve sort of said this before, I really love negative working capital companies. It’s one of the reasons I like e-commerce marketplaces. I like anything where people pay you first and then you do what you do. Like, so I mean, they’ve got negative cash flow or negative working capital on their balance sheet. They’ve got virtually no debt. I mean, it’s, the thing’s a cash machine. And you know, if the party keeps going, that’s awesome. But it all depends on. You know, their games being one of the very few blockbusters, they need to have that suite of games. Okay, so what’s the point? I mean, this is a digital strategy podcast and I don’t think I’ve told most of you anything you didn’t know if you’re at all familiar with gaming. I mean, what’s interesting on the strategy side? How do you take this apart? Okay. What I like about gaming and what I don’t like is the same thing is… the power is so focused on two areas. It can be a great business or it can be the hardest business ever. Clearly the consumer side, I mean, is there a business with a more powerful grip on people’s minds and interactive gaming? I mean, think how different that is. Like when you sit and you watch Netflix and you’re just kind of vegged out on the sofa, your brain’s not active, it’s passive. Compare that to playing video games. Look at the level of engagement people have. I mean, they are totally switched on. They’re deep into the game. They will play for hours. Have you ever played video games and you look up and it’s like two hours later? And you’re, it’s kind of like, how in the world did that happen? Like you just zone out for a while and you’re chatting with your friends and then you stay in the games forever. You play them for years. You build up your characters. And then that’s just the game. And then there’s a whole world around this of like a fanboy culture where people make videos on YouTube to talk about the game. And if you’re selling stuff on Amazon, people aren’t making a lot of videos about what you’re selling, but you have a video game. It’s like a whole world of content creation and influencers talk about you. I mean, it’s really powerful on the consumer side. The other side is when we look at the business model. I always consider like, most of these games to be, want to be platforms. They clearly want to be platform business models. Now an e-commerce site, Alibaba, marketplace platform. What is the platform? It connects two user groups, it enables an interaction. The interaction is a transaction. YouTube connects two user groups, content creators, content viewers. What is the interaction it’s viewing? So I’ve called those audience builder platforms. because you’re not doing transactions, but you’re building audience. I think that’s the primary goal. I’ve always actually, if you look on my list of five platform business models, I’ve always called audience builders innovation and audience builder. I consider audience builder like a YouTuber or a TikTok, a subtype of an innovation platform. What’s an innovation platform? That’s when you’re connecting two user groups. let’s say a consumer watching a video or playing a game, and a developer on the other side. And the developer is not necessarily there to build an audience, and they’re not necessarily there as a participant in a marketplace. Their primary goal is to create something new. And so they need lots of tools. They wanna build a video game. They wanna build software apps. Everything on your smartphone, all those mobile apps. those were created by people and you could consider Android an innovator, I’m sorry, an innovation platform. I think most video game platforms are innovation platforms. They just don’t have that many participants. I mean, there’s a gazillion companies that make mobile apps for your smartphone. There are a lot of people who make video games, but very few of them get traction. But I think that’s basically, I consider it like a half broken innovation platform. And you can see companies trying to get around this all the time. It’s like, look, we’re not going to go for the most complicated, immersive multiplayer games like World of Warcraft or Ghosts of Tsushima. We’re going to go for casual gaming. And by going for casual gaming on a smartphone, you know, I know slicing pieces of fruit. that will open up the world of developers and more developers can innovate on our platform and we will expand the platform and that’s I think that’s what they’re going for with innovation platforms but none of them have really taken off that well. The market is still sort of heavily tilted towards these very rare high quality deeply immersive games but that’s kind of that I view that as a half broken innovation platform and then these casual gamers trying to build platforms on smartphones. I think that’s kind of like you can consider the App Store as a full innovation platform for gaming. Because most of those games are simple little, you know, shoot the rocket or whatever. Okay, so that’s kind of how I would describe it as a platform business model. But then you got to look at the content type. You know, music has a very different type of consumer behavior than videos, than short videos, than live streaming. then high quality movies, then garbage movies, then high quality songs versus indie songs which nobody wants to hear. I mean, gaming is really shaped by the type of content. And it’s surprising how consumers view different types of content so differently. They really do, I mean, one of the reasons Spotify looks the way it does is because they’re totally dependent on licensing popular songs going back 30, 40 years. But if you do get those licenses, consumers will listen to the same song over and over and over again for years. They don’t do that for TV shows. TV shows is kind of a mix. We could watch some YouTube videos, but maybe we want the TV shows as well like Game of Thrones. But nobody wants to see the popular TV shows from the 70s. And if they do like a TV show, they only watch it once. So you can see how consumers view different types of content. It shapes the type of platform. And then ByteDance, because they’re super smart, they basically got the type of content, short video, which is incredibly well-liked, but has probably the most attractive business model. Anyone can create it. Quality doesn’t matter. They get it for free. People watch them like crazy, and they’ll just keep watching over and over for, I forget what the TikTok consumption rate is. It’s like 90 minutes a day now. on TikTok up from like 45 minutes a day per user a year ago. And your Facebook is stuck at 20, 25 minutes per day. I mean, it’s crazy. It’s kind of Instagram is similar. It’s just a beautiful business model tied to a particularly popular type of media. Anyways, okay. So that’s kind of how I put this in the strategy bucket. Then you start to think, okay, platform business model. Does it have a network effect? For the most part, no. No, I mean what you’d be looking for if we’re talking about Microsoft Windows innovation platform, full innovation platform, two-sided indirect network effect. The more people writing software for Microsoft the better it is for the users of the PC and vice versa. You know, but they don’t help each other so fine that’s a clear example but these half broken innovation platforms don’t really get an indirect two-sided network effect because there’s just not that many So really what you’re seeing is not a network effect on most of these companies. What you’re seeing is just a B2B service for creators. That companies like Epic Games, they will offer lots of tools to creators, like the Unreal Engine, and increasingly they’re offering operating tools, like the ability to market your game and get paid and add social and other things. They’re really in the B2B service business more than they’re in the platform business. Okay, so that’s kind of traditional. strategy view of gaming 1980 to let’s say 2010 ish. Console wars, if you ever want to read good strategy, read the console wars, Nintendo, Atari, why they ended up with sort of a blades and razors business model. We’ll sell the consoles very, very cheap and then we’ll make our money on the games, which is kind of how Bic sells razors. Starts on the PC, it goes to console. eventually it starts to go online. You see companies like Steam. But within there probably in that period of time, 1980, 2010-ish, the most interesting stuff, if you weren’t a successful developer of games, the other point of power was the consumer engagement. And these companies, whether they’re like Steam or Sony or whatever, they are so good at creating I mean they’re the masters. They are all the tricks, all the loyalty points. We’re going to have this game with multiple levels, but we know how hard to make each level such that you stay engaged and don’t get too frustrated and leave so you can level up. I mean they’ve mastered the whole thing of keeping you in a game for hours and years. They give you points, you can buy new skins, you can buy a virtual game, you can give… You can get all of this stuff. They get you invested. They make it the most engaging version of the game. I mean, they’re just amazing at it. I think nobody has mastered this idea of how do you get consumer engagement with software like the gaming companies have. And then you can see the e-commerce companies and everyone else are kind of copying them. Okay, and then we get to 2010-ish. And the strategy thing starts to get a lot more interesting. That’s kind of when it came in more into my world. I never had much to say about gaming before that. There just wasn’t that much strategy going on. Okay, 2010-ish, a couple things happened. One, mobile games jump in, because everyone’s got a smartphone, and we start to hear this discussion of immersive games, the most complicated ones, versus casual games you can play on the smartphone. And as I said, there was this idea, let’s… let’s do casual games on a smartphone because that lets us build a full innovation platform, not a sort of half broken one. The freemium business model really takes off. People start to add services, live services, live ops, and instead of hey you buy the game, you play it for a while. Now it’s like hey you buy the game and you get a subscription ongoing and we’ll give you the first bit for free, right? So freemium business model takes off. That’s always a good idea. But the big one in terms of strategy was multiplayer. Multiplayer. Suddenly the game is us all playing together. Now that happened a little bit before 2010, but I mean, that’s World of Warcraft, that’s MMORPGs, that’s Battle Royale. I mean, it’s just, why is that important? Because it gets you a real network effect, right? If there’s only 20 games we like playing, there’s no… two-sided indirect network effect between players and game developers. But if there are millions of people all playing a game together or doing tournaments together, the more people I can play with, the better it is for all of us. So it’s a one-sided direct network effect. And so a lot of these companies, like let’s say MMORPG, they started to get direct and somewhat indirect network effects at the same time. The more people you play with, the better it is. But it’s also a little bit like, okay, but do I just wanna play with random people? No, I wanna play with my friends. Maybe friends that I meet online, but maybe colleagues from work and we all play at home after work. We all go home and we meet up online and we all play whatever. So if the first big lever was multiplayer, which gets you your direct network effect, the second lever is social. It’s almost like a social network. It’s almost like a community. You know, if all my colleagues from work, we’re all playing whatever battle royale late at night after work together, you know, it’s a social network. Kind of. So that’s, let’s call that the second big lever. Third big lever, tournaments, right? Turns out people love competition. I mean, it’s just everywhere. Esports, obviously, they already knew that. Free Fire, PUBG, Battle Royale, I mean, we have at least three big levers that change the strategy aspect in a major way. Multiplayer, social networks, or at least community, and then tournaments and competition. And usually the tournaments the ones people like are live. Those tend to get more engagement. So you’ve got those three levers, and if you go back before looking at skills, which I’m gonna get to right now. I mean, that’s kind of what you see all these companies doing. I mean, isn’t that what Epic Games is doing? Isn’t that what Garena is doing? That’s where they’re all focused, and it’s really powerful. And it’s so powerful that Epic Games is now challenging Apple. I mean, this is the first time. There’s only a couple of real ecosystems in this world. Google has one, Apple has one, Tencent has one. Epic Games has become so powerful that they are now going head to head with Apple about the you know, the fee you have to pay to be in the app store. And they may be strong enough to do it. So, I mean, we’re seeing the first gaming ecosystem emerge with a level of power. We have only since seen in Apple, Google, Tencent, maybe Alibaba. So it’s a big, big deal. And I think that’s a result of these three levers being pulled. Okay, which brings me to skills. Now, Skills was founded in 2012 by Andrew Paradise. This is another dude, but I think it’s mostly Andrew. Founded in Boston, although it’s moved to San Francisco since, big surprise. And it’s a really interesting play. What they’ve basically done is they’ve let developers, they’ve created a platform, a set of developer tools that let game developers basically turn any mobile game they have into an e-sport. So you can basically run competitions all day long. That’s really what they do. They do competitions. So it’s an online mobile multiplayer video game platform that does competitions. And it’s only on smartphones, so iOS and Android. I think it’s only on smartphones. Mostly on smartphones. and you can compete with various players all around the world in fairly basic simple games which they’ve launched by the hundreds, probably thousands at this point, and they host millions of tournaments every single day. So you log in, they say, hey, do you want to play this game fine? And then they match you up with other players and you compete. Okay. Well, that’s not too different than what I’ve just been talking about. Okay, multiplayer, check. Social, no, not really. Tournaments, yes. So what are they doing that’s different? What they’re doing that’s different is you get cash rewards. So you play, it’s a competition and whoever wins gets a prize. And what’s the prize? Cash. Now that’s a new thing. Now it’s not. quite that simple. There’s a little bit more to it than there. You basically play in these competitions and some of them you can play for free and others you have to put in money to join, so there’s a fee to join the competition. And then if you win, you get a certain amount, here’s the prize for this competition, you get it, it goes into your account within skills, then you can use it to turn it into various prizes, merchandise, or you can use it for future paid entry into other competitions. So I don’t think as far as I can tell that they just send you a check, oh, you won. Now they’re sort of keeping you in there, you can convert it. And obviously there’s a lot of complexity in there I’m not too up on with regards to what you can do with cash in and cash out within the iOS store and Google Play. Now from what I’ve read, the way they’re doing it now, one, it doesn’t violate any gambling laws. We’ll talk about that in a minute. And two, it doesn’t require Apple or Gouldy take 30% of the money in. As far as I can tell, I’ve been looking into it, but it’s, it’s a, I mean, this is the whole crooks of the Epic versus Apple fight is when does Apple get 30% of every in-app purchase? When? If you take the money out, if you put it in, what if they give you a reward and then you reuse the money for another game? Does that count? So they’re basically in the cash prizes. for tournaments business on smartphones. You call it competitive mobile gaming with cash rewards or cash prizes. Now they will pitch this in their filings. It’s a public company, you can pull all this. Why is this good? They will pitch it to something like, well, there’s a mismatch between how developers work and make money and what consumers want. How do you monetize games today? Well, you put in app ads. but people don’t really like those. You could put prize boxes or something in the game. A lot of times consumers really hate that. You can do skins and all that, but it’s a more direct mechanism, you could say, of monetization that puts the developer and the consumer effectively on the same page. That’s their pitch. As far as I can tell, I basically agree with that as an argument. I just don’t think that’s really what’s going on. Okay, so let’s say you’re in the tournaments for prizes business, and the distinction that’s important is cash prizes. Well, what do they have? Well, they have live operations, just like Electronic Arts, because you’re putting together these live events, lots of users sign in, and you know, you have to make the game fun. If you go into a game and you just get blown out after you paid to get in, that’s no fun. I mean, people won’t do that very long. So there’s a whole sort of matching of skills that they have to do. They have to assess player skill and they have hundreds of metrics, apparently. So that when you sign up, they can sort of match you with the right team. And then the question they say is, look, there’s a trade-off in the algorithm. Do you want the fairest game to play or do you want the fastest game to play? Because the fairest one where it’s really evenly matched and you’re having fun and you have a good chance of winning. might take some time to set up versus the fastest game, this is the one that’s available right now. So there’s a look, there’s an interesting sort of algorithm thing going on there. But they have so many games on the platform and such a high frequency of tournaments that you can see, okay, it looks like there’s probably a direct network effect going on there. So here are some numbers on usage. They basically offer about a hundred million dollars worth of But they have a couple games, Tether and Big Run. These are basic simple games like Bingo and stuff. That makes most of their revenue overall. So yes, a lot of activity, big money, but it’s coming from a couple really simple, I would almost say commodity games. They say there were 36 games they have that generated over one million annually in GMB. That was up from 23 games the year before. So yeah, you’ve got the big, big, big. popular ones, but there’s other smaller ones and there are a decent number of developers on the platforms in quite a lot of games. Monthly active users in 2020 was 2.6 million people. That was up from 1.6 million in 2019. The average revenue per paid user, about $7. That was also up from about $6 in 2019. The distinction that matters is the paying MAUs versus the regular MAUs. It’s a freemium model. Everyone can play, you can compete, but at a certain point you start paying to enter tournaments. That’s about 13%. 13% paying MAU over a regular and total MAU. That’s up from 10%. Interesting, so about 300,000 paying MAUs in 2020, which was up from 200,000 the year before. And when the money goes in and they compete and they win… It looks like most of the money stays in the game. So even if they’re paying in and they’re winning competitions, the money goes in their account and they’re using that to sign up for more paid competitions. Now something cool about this company is they publish their cohort numbers, which most companies don’t do, which is really frustrating because it’s incredibly important. But their cohort numbers are also spectacularly good. So they look… here I’ll give you some numbers. So they’re two hundred and… 2016 cohort. So all the people that signed up started using it in 2016. In year one, they spent about $6 million. So out of that first cohort, $6 million in the first year. In year two, it drops to 5.8. That’s actually kind of common when you see cohort analysis the second year often will drop. But then it bounced back up in year three to, well, 5.6-ish, year four, 6.6, year five, 7.2. So that same cohort of people from 2016, you’re five years later, is spending more than they did the first year. So they’re keeping people. They’re not leaving and they’re spending more and more. That’s, I mean, you see the same thing in Amazon. The longer people stay at Amazon, the more they spend year after year. The cohort numbers are crazy. And then you jump forward a couple years, let’s say the 2019 cohort. uh… mom the numbers have gone through the roof i mean it’s no longer five or six million it’s thirty million forty million two thousand nineteen court sixty five million dollars spent in your one two thousand and twenty cohort hundred and sixteen million spent in your one if the same phenomenon happens where they all stay these dramatically bigger numbers are going to be really impressive it’s really Okay, there’s the idea, there’s the usage numbers, they all look good, they actually look surprisingly good. And then you get to the financials. Okay, and the financials are not good. Revenue is, you know, 2020 revenue, $230 million. Now recall, for Electronic Arts, we were talking $5 billion. Why? Well, you could say because it’s earlier stage. I would argue this is a much smaller niche audience. This is not mass gaming that everyone participates in. This is people who are going after cash prizes. So we’re dealing with a smaller demographic here. And the revenue is going up. I mean, 2018, they were at 50 million. So they doubled in 2019 and then 2020 went up by another 10 or 15%. If you look at the cost of revenue and the gross profit, it actually looks pretty good. But then when you look at their sales and marketing numbers, so let’s say 2020. $230 million of revenue, their sales and marketing spend was $252 million. So now that would not be uncommon in a rapidly growing small company. We often see that in digital. People are just going to blow out the sales and marketing spend. And that is always what they’ll say they’re doing. Often that’s not what they’re doing. Often what they’re doing is they’re trying to keep a network effect going and their cost acquisition for customers is high and getting higher, but they have to keep spending to keep the traffic. Now, skills actually breaks out their cost of acquisition per customer versus the lifetime value. And they basically say, you know, it’s about 3.8 or four. So the value of a cohort would be 3.8 to four times what they spend to acquire that cohort. Now, I think that’s probably what they’re doing. They’re blowing out their marketing spend because they’re going for growth. You know, so this thing could become profitable. I mean, the numbers for Shopee looked very similar to this in the first one to two years of them launching that thing. And then, you know, the revenue took off and they started to dial back the sales and marketing a bit and suddenly it became, you know, the numbers started looking real good. So you could be right in that moment. So what’s going on with this company in terms of strategy? Well, this is sort of the so what for the whole podcast. I laid out three big strategy levers a company like Electronic Arts was pulling. Multiplayer, tournaments, social network. They’re not doing it as much. A company like Roblox, I would argue, is almost entirely about the social and community aspect and not the gaming aspect. Okay, what is it that skills can do that these companies aren’t doing? I mean, skills isn’t bringing anything to the table. that a company like Electronic Arts or Epic doesn’t have and hasn’t been doing for a long, long time. The games are much better. These are fairly basic, simple, casual games. The multiplayer side is not going to be more advanced. The tournaments aren’t going to be more advanced. What is it they’re doing? Now I think they are reaching for the fourth big lever, the one, the lever that the other companies aren’t pulling. And that’s the gambling psychology level lever. they’re basically offering a casino. I mean, this is sports betting. No sports playing and betting. I mean, that’s really, what else is this company doing that the other gaming companies are not? Nothing. Now, is it because the other gaming companies couldn’t do this? No. I think it’s because they chose not to. I think this is a good strategy. I’m actually a big fan of this strategy. If you can’t do what your competitors, if you can’t find something that you can do that your competitors can’t, find something that you’re willing to do that they aren’t willing to do. I don’t think Epic Games is gonna start putting cash prizes in the games. Why? Because it’s largely regarded as, you know, these are sin stocks. Casinos are, you know, they’re regarded alcohol companies, cigarette companies. They’re generally called sin stocks. And a lot of businesses don’t want to go into that. Starbucks doesn’t sell cigarettes, as far as I know. Not a lot of companies want to go into the cigarette business. Not a lot of companies want to go, alcohol is pretty mainstream, but let’s say gambling. A lot of companies avoid gambling, lotteries, things like that. For one, once you move into the gambling side, the regulations get a lot more complicated, especially in the U.S. Now the distinction that actually Skills talks about in their filings is that the regulations mostly distinguish gambling as when it is a luck-based game and not a skills-based game. which is what they say and they say we believe we are under the skills-based category although they’ve never been officially ruled on by a state gambling associations is whatever Maybe that’s the regulation, I don’t really know. I don’t really think it matters. I mean, if I go into a casino, I’m pretty sure there’s a slot machine. Okay, that’s a luck-based game. Pull the lever, did I win? I walk 10 feet to the left and there’s blackjack. I’m pretty sure that’s a somewhat of a skill-based game, although the odds are against you. So does that matter? Meh, I don’t know. You know, I think that the interesting thing here is what is, why is this a big lever on the consumer side? It’s because gambling is a huge psychological effect on certain people. It absolutely is. Like if you ever go to Vegas, you’ll see slot machines in the liquor stores, in the shopping mall. You’ll see slot machines in the airport terminal. And people just sit in front of those things, especially slot machines, and they just pull that lever over and over and over and over. And there’s a great book called Addiction by Design, which talks about this psychology of gambling. And usually what people point, there’s a lot going on within that. Like, why do people go to slot machines and casinos? Is it to win money? No, they know they’re not gonna win. They’re not going in, I’m gonna go into the casino today and make a lot of money, what’s my odds? That’s not, I mean, some people are doing that, like professionals and skilled people. The vast majority are not. What they’re doing is they’re plopping themselves in front of a chair, they’re zoning out, they’re kind of in a trance, they scare the screen. They pull the lever, pull the lever, pull the lever all day long, and then all their money’s gone, their big bucket of coins, and then they go home. So it’s not about winning the money, it’s about the gambling process. And it’s a really interesting phenomenon. Gamblers talk about getting into the zone, where they almost get into a trance-like state, where they pull the lever and then there’s a thrill of, am I going to win? And then you usually almost win, which is a… a psych phenomenon. You get two blackjacks and a lemon. It’s like, oh, I almost won and I pull again. Most digital companies do some version of intermittent variable rewards. You know, you post a link on Facebook and then you check back to see how many people liked it. That’s a type of reward, but it’s intermittent and variable and it’s more addictive when it’s variable. And sometimes you get a lot of response to your tweet and sometimes you get none. People check back. So there’s intermittent variable rewards, this is a psych phenomenon. There’s the almost win phenomenon, which Charlie Munger talks a lot about. He says, like, if you see a casino and one slot machine is making dramatically more money than the others, what’s different about it? And his answer is that machine has been programmed to give you almost wins because you get, you know, blackjack, blackjack, whatever you call it, diamond, diamond, lemon. Oh, I almost won. And then you pull again. If you set that machine to give almost wins, you get a much more powerful effect. Okay, with that in mind, that whole thing I just talked about skill matching, we’re in the skill matching business. We’ve got to get players in games where the skill of the other players is about the same so they have an ability to win and it’s a fun game. Now that’s one explanation. Another explanation would be like, are you engineering almost win scenarios? Oh, I almost won. I was so close. If you go into games and get blown out, you’re not going to come back. You could read that either way. Yeah, the psychology of gambling is incredibly powerful. So how does this change the strategy? Well, the other concept for today, two concepts for today, one was network effects, which is an interesting scenario within gaming because they typically haven’t had great network effects between developers and consumers, although it’s better with casual gaming. And then multiplayer, that was important because you got direct one-sided network effects for the first time really. And then this is kind of, okay, I don’t think this is dramatically different in terms of network effects. I think what it’s doing is it’s changing in terms of share of the consumer mind. What is your share of a consumer mind? That’s a type of competitive advantage. It’s a Warren Buffett phrase. Does adding gambling to gaming change its hold on people’s minds? And I think the answer is absolutely yes. And if you don’t believe that, go to Vegas or Macau. Those cities are built on this psychology. That is the whole basis of their economy, is the effect of gambling on people’s brains. Everything else is secondary. They also sell you alcohol and, you know, there’s a lot of other sinful behavior going on, but that’s the big one. I mean, look at the financials for casinos. They’re unbelievable. The only time I see financials that amazing is like cigarette companies, which is another type of sin stock. And that’s kind of how I see skills. And I’ll leave it with the question, which is how far are gaming and other companies going to go down this path towards digital sin stocks? How far are they going to go? I did a podcast a couple of weeks ago called Evil Motes. You know, heroin has a very powerful share of the consumer mind. It absolutely does, much more than cigarettes. But it’s outlawed. And you see a lot of digital companies using various tricks to get people, you know, they’re doing technology created habits and addictions. And you see a lot of companies sliding down that path. Facebook is absolutely in the habit formation business and the dopamine addiction business, and then that’s not terrible in itself. Coca-Cola is in the sugar business. I don’t think that’s terrible. It’s in the caffeine business. So it’s a matter of degree. And how far are gaming companies, maybe more than that, how far are they gonna move into the sin stock area? Are we gonna see lots and lots of digital sin stocks? The same way we see them in alcohol, nicotine, addictive substances, things like that. You could argue pornography, similar. certain industries definitely have a temptation to go down that path. And I don’t necessarily think it’s wrong, but I think it is a different type of thing. And well, at a certain point, I think it’s wrong. I mean, heroin’s wrong, but there’s a lot of gray in there. Is a bunch of people spending one to two dollars to gamble on a bingo game on their phone? Is that really a big deal? As opposed to, oh, you know, I have a relative who has a gambling problem. I’ve known a couple people like this where they lost a ridiculous amount of money and basically crashed themselves. Now that would be easier to pass judgment on. Is a lot of people spending a dollar on their smartphones every couple days really a big deal? I don’t know. But anyways, that was kind of the point of today, this idea of the sort of evolving strategy and business model for gaming and how far it is going to move into this sort of, let’s say, digital sin stock characterization. And I think electric arts and skills are both sort of good counter examples to this. But you know this could end up being a ridiculously profitable company. You know if you could have owned a casino 30 years ago, you could have retired. So, you know, just because maybe it has moral questions doesn’t mean it can’t be ridiculously profitable. The profits on cigarettes are still unbelievable. It’s just that the governments are taking most of them now. the regulators in some countries and I think probably Google and Apple will be the ones who determine how far this goes. I think they’ll put the brakes on certain parts of this if it goes too far down that path. But we’ll see. Anyways, that’s it for content. The two concepts for today, share of the consumer mind and network effects. Anyways, that’s it for me. I am still here in Rio. I’m actually… I’ve got an apartment here. I’m looking out over the lagoon, which is spectacular, but there’s a bit of traffic outside, so you’ve probably heard that during this talk. It’s been great. I’ve been riding away, hitting the gym every day, feeling good. It’s just a beautiful place to live, at least for a while. And then I ended up, it looks like I’m gonna do a bunch of meetings here with some investor groups, which is interesting, because there’s a lot of interest apparently. out of Brazil about China Asia tech. I mean, there’s a lot of copying going on from Latin America to China Asia. So it looks like I’m doing quite a few meetings in the next week. One of the ones that I’m pretty excited about is the 3G Capital team, because 3G Capital, I’ve studied them for a long, long time. George A. Paolo and those three guys that sort of built this unbelievable investment empire. And they have family offices here that do investing. So I guess I’m gonna talk to them. which is great because I’ve been trying to meet them for years. So anyways, that’s going to be the week, but I think I’ll sign off because I’ve been talking at you kind of a lot today. But yeah, this is going to be a pretty spectacular month. My idea of coming to Rio for a month on almost a whim turned out to be one of my better ideas. So anyways, it’s great. Okay, I hope everyone is doing well. I hope everyone is staying safe and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.