I did a podcast talking about scale advantages (and scale disadvantages). And about how scale advantages are different than economies of scale. They are also different than competitive advantages.

But because scale advantages has the words “scale” and “advantages”, these concepts often get mixed together.

You’ll see this in the writings of Charlie Munger, Michael Porter and Michael Mauboussin. And by lots of value investors (who are super obsessed with competitive advantages).

So, I thought I would clarify the various concepts. Or at least put my definitions. And they are different.

–

The short version is:

- Scale advantages are bigger as a phenomenon but fuzzier. And hard to measure.

- Moats (including economies of scale) are more precise and can be measured.

Why Growth Plus Scale Advantages Is Still the Default Business Strategy

Being a big business is better than being a small business. Mostly. Definitely up to a certain size.

There is just a big difference between being a 20-person firm and 200-person firm.

- Small firms are limited by fewer staff and resources. They can’t launch many projects.

- They have less management depth and expertise (usually).

- They have less access to financing.

- And they are more exposed to shocks. They have smaller revenue and less product diversification. When hit by turbulence, there is a big difference between flying your plane at 30,000 feet and at 50 feet.

But when you grow in size, you get all sorts of advantages with scale.

So, what are the scale advantages?

Well, it’s kind of a big fuzzy list.

Here’s a list from a business analyst named Brian Feroldi who posts on Twitter.

He’s talking about cost advantages that come from scale. Which includes:

- Lower unit costs

- Increased bargaining power

- Access to financing (lower rates)

- More and specialized tech and innovation

- Better and specialized staff (effective and efficient)

- Brand awareness and marketing spend

- Diversification

- Reach and resources

And this is mostly true. My list would be a bit different. And I would include demand-side scale advantages like brand awareness and information advantages. Plus, management advantages are really important. As you get bigger you get greater management expertise and ability. And more specialized management.

But the basic idea is you get lots of advantages when you get bigger.

Here’s another framework by Brian.

So, scale is really valuable. And therefore, growth is the default strategy for business.

It’s also worth noting that most scale advantages are available to every firm in the industry. It’s not about relative scale, where only the market leaders has advantages. Everyone can and does get advantages with scale.

Another point to consider.

Much of my digital strategy stuff is driven by the following chart by McKinsey & Co. It’s my worldview.

It’s a good summary of how digital is making business much harder. And the distribution of winners and losers is getting more extreme. More and more of the profits are going to a smaller group of companies. And being just ok is not as survivable as it used to be.

So, that’s another reason to go for growth. It’s your best offensive and defensive strategy in this type of business world. You always want to be fighting to grow into the top quartile (that’s where the big profits are). And you want to be fighting against falling into the bottom quartile.

When Scale Advantages Stop Working

In traditional industries (i.e., not digital), diseconomies of scale is always a problem at a certain point. This is also called scale disadvantages. Jack Ma calls it “big company disease”. I’ll go into this below.

And there are also some businesses that can’t scale. I spoke about this in the podcast on fragmented industries. In some industry types (restaurants, hair salons), it is next to impossible to get significant market share. And if you do, you will likely hurt your core service levels.

But digital might be changing this too. Most fragmented industries are about grappling with changing and complex customer demands (people like lots of choices of food types) and the difficulty of scaling human-based operations with lots of customer interactions. AI and AI+Robots might solve these problems. We’ll see.

I Think It’s Better to Analyze Scale Advantages Using 5 Forces

So, scale advantages are big. But it’s kind of fuzzy as an idea. You get these long lists of various advantages that happen when you grow.

I prefer to look at how scale impacts each of Michael Porter’s 5 (now 6) forces.

- Bargaining power of suppliers

- Bargaining power of buyers

- Rivalry with competitors

- Barrier to entry against new entrants

I’m not looking at complements or substitutes here.

You’ll notice that Porter’s forces are already about scale differences. If the suppliers have greater bargaining power, it is probably because they are more concentrated. One hundred companies buying from 4 suppliers will have less bargaining power and scale.

So, I like to look at supplier power and buyer power as current or potential scale advantages or disadvantages.

For example, if you are a branded CPG company trying to sell through Walmart, you are in a weak position as a supplier. You are at a scale disadvantage between buyer and seller. And this can be measured and tracked.

And it’s not just you. Most all the branded CPG companies are. So, we are looking at a scale disadvantage that is absolute, not relative. It’s a result of industry structure. And being larger than your rival is not necessarily going to get you anything different in your supplier terms with Walmart.

Similarly, if you are a dental practice in the USA, you are probably getting your supplies (and other services) from dental distributor Henry Shein (a compelling company). It has 30-40% of the market for dental distribution in the USA. That makes it pretty powerful as a supplier to the approximately 200,000 professionally active dentists in the U.S. (in 2023), who average 1.7 dentists per practice.

Scale advantages with buyers and sellers work the same way. Being one of 2 big hospitals in a small town means you have a scale advantage with consumers (and insurers sometimes). Being a big and popular shopping mall in your town gets you bargaining power over lots of smaller brands and stores.

The other two forces are:

- Competitive advantages against rivals

- Barriers to entry against new entrants

This is mostly what I focus on. These are usually relative scale advantages, where only the leaders get them. I’ve written like 8 books on this particular topic.

What I like about this approach, is you can see where the scale advantage is coming from. And it’s measurable.

Scale Advantages Can Cascade

This is a Charlie Munger term (I think). He says scale has lots of advantages (as mentioned). But also, that they can lead to other scale advantages. They can cascade. Here is his example.

- A big CPG brand can have a scale advantage in production and distribution.

- This can lead to a scale advantage in marketing spend.

- This can lead to an information and awareness advantage (consumers are more aware of brand). This advantage is both about information and psychology (consumers are more comfortable. It can be a habit).

- This can also create a social proof advantage. People are influenced by what others do and want. There is also greater trust when you see others buy something.

- You can also get specialization advantage (production, investment, technology, etc.)

But they can cascade. It’s a nice idea. I like to look for competitive advantage flywheels, which is similar.

GE CEO Jack Welch famously only wanted to be #1 and #2 players in a market. Or he would exit. The big scale advantages just got the leaders too many advantages.

I should also point out that in certain businesses you can see increasing returns at scale. We see this in ecommerce marketplaces and other digital platforms. As they grow, we see increasing margins. Network effects can actually increase value with scale.

Scale Disadvantages (i.e., Big Company Disease) Are Under-Rated and Under-Measured

As mentioned, at a certain point scale advantages get overwhelmed by scale disadvantages. They include:

- Slower speed.

- Increased bureaucracy and internal self-interest.

- Increased complexity.

- More exposure to specialization plays.

- Internal information and communication problems.

- Less aggressive management.

Charlie Munger said that increased scale always gets you increased bureaucracy. Which leads to misaligned incentives and corruption. And that government bureaucracies are the most prone to this as they lack competitors.

Scale advantages plus disadvantages gets you the following graphic.

I think this is mostly true. You just don’t see firms bigger than a certain size. There are not 10M people companies. There are no banks that sell 10,000 types of checking accounts. Human-based organizations just don’t seem to work beyond a certain size. But AI Agent-based organizations might not have this limitation. We’ll see.

Porter and Mauboussin Have Lists for Barriers to Entry and Competitive Advantage

Ok. So, staying the other two forces:

- Competitive advantages against rivals

- Barriers to entry against new entrants

Let’s look at how some pretty smart people talk about them.

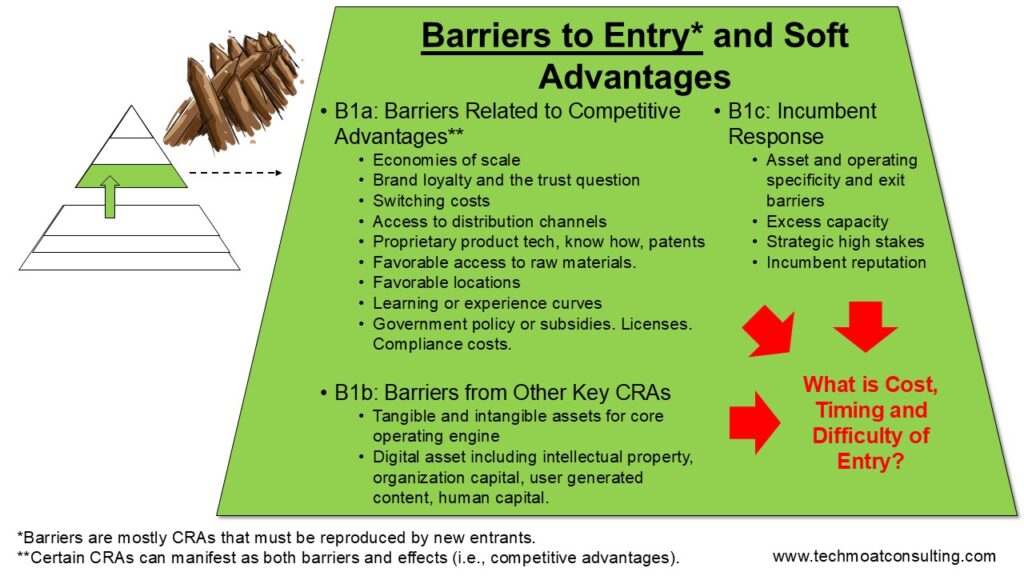

Here is a list of Barriers to Entry from Michael Porter. It’s not exhaustive and is my interpretation and comments.

- Economies of scale. Yes, you need to get big to enter an industry. And the indivisibility of production capacity and purchasing power are a big factor in this. He also notes that being a multi-business or vertically integrated business can change this. It can help both the incumbent and entrant as you can share costs, brand, etc.

- Brand loyalty. You need to spend to overcome customer loyalty and habits. You often need to overcome a trust problem too.

- Capital requirements. Entering is riskier if the costs are not recoverable (i.e., the marketing and R&D spend are gone).

- Switching costs.

- Access to distribution channels. You need to convince retailers to carry your product.

- Cost advantages not related to scale. This is similar to my list of variable cost competitive advantages. Porter includes:

- Proprietary product technology / know how / patents / secrecy.

- Favorable access to raw materials.

- Favorable locations (at the right cost).

- Government subsidies.

- Learning or experience curves.

- Government policy. Such as a licenses and compliance costs.

You’ll note that his “barriers to entry” list have a lot of stuff that sounds like competitive advantages against rivals. Economies of scale can definitely be a barrier to entry. But it can also be a competitive advantage against rivals (Coke and Pepsi versus smaller sodas).

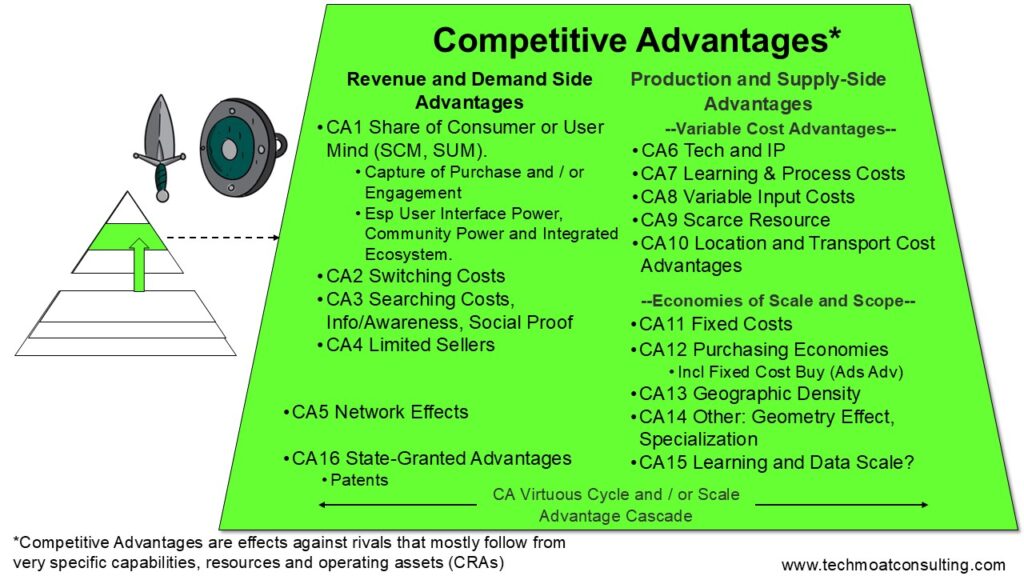

We see the same blurring with Michael Mauboussin’s discussions on Competitive Advantages. This is also not exhaustive and is my interpretation. But a lot of this is his language.

- Customer Switching Costs: When customers face significant costs (financial, time, or effort) to switch to a competitor, companies can retain market share and maintain pricing power. Examples include software platforms with entrenched user data or services requiring retraining.

- Network Effects: A product or service becomes more valuable as more people use it, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that deters competitors. Social media platforms or payment networks like Visa are classic examples.

- Economies of Scale: Companies with large-scale operations can spread fixed costs over greater output, reducing per-unit costs and enabling lower prices or higher margins. This is common in industries like manufacturing or retail (e.g., Walmart).

- Intangible Assets: These include patents, trademarks, brand reputation, or proprietary technology that competitors cannot easily replicate. Strong brands like Coca-Cola or patented drugs in pharmaceuticals illustrate this advantage.

- Cost Advantages: Firms that can produce goods or services at a lower cost due to unique processes, access to cheaper inputs, or proprietary methods gain an edge. This could stem from process innovations or exclusive resource access.

- Efficient Scale: In markets where a limited size supports only a few players profitably, established firms deter new entrants. This often applies to niche markets or regulated industries like utilities or airports.

Mauboussin also has lists for competitive advantages related to production. Again, this is my interpretation of his thinking. Most of this is my language.

- Production:

- Complexity matters a lot in production. Think Toyota and its process power (from H. Helmer).

- Indivisibility also matters. Do you need to buy or build capacity in large increments?

- Patents

- Process advantages and learning advantages. These can be hard to replicate. Mauboussin says what matters is the rate of change in the process costs.

- Scarce or cornered resources. Resource uniqueness.

- Lower cost of inputs / purchasing economies – such as bargaining power with suppliers.

- This is mostly purchasing economies as a type of economies of scale. It can be amplified by indivisibility of purchasing. In the 1960s, you could only buy TV ads nationally which made it something that large brands could afford. But smaller brands couldn’t.

- Distribution. I usually put this in with economies of scale in Logistics and Distribution.

- R&D spending and ability.

- Advertising spending and ability.

Those are useful lists. Lots of good factors to consider.

But again, it’s kind of messy in my mind. Here are my lists.

My Playbook: I Separate Barriers to Entry and Competitive Advantages and then Ask 3 Questions

Ultimately, I want to know 3 things:

- What are the barriers to entry against new entrants?

- What specific CRAS must be reproduced?

- What is the cost, difficulty and timing to enter? Give me numbers.

- What are the competitive advantages against rivals?

- Which competitive advantages matter specifically? Against larger and smaller rivals?

- What are the numbers to track for them?

- What is the incumbent or rival response?

That’s pretty much my assessment. And I am mostly focusing on two of the 4 forces. I will look at the absolute scale advantages when doing Porter’s 5 Forces. But I am mostly interested in competitive advantages and barriers to entry. To me, that is the moat. That is the structural advantage.

I also have specific definitions.

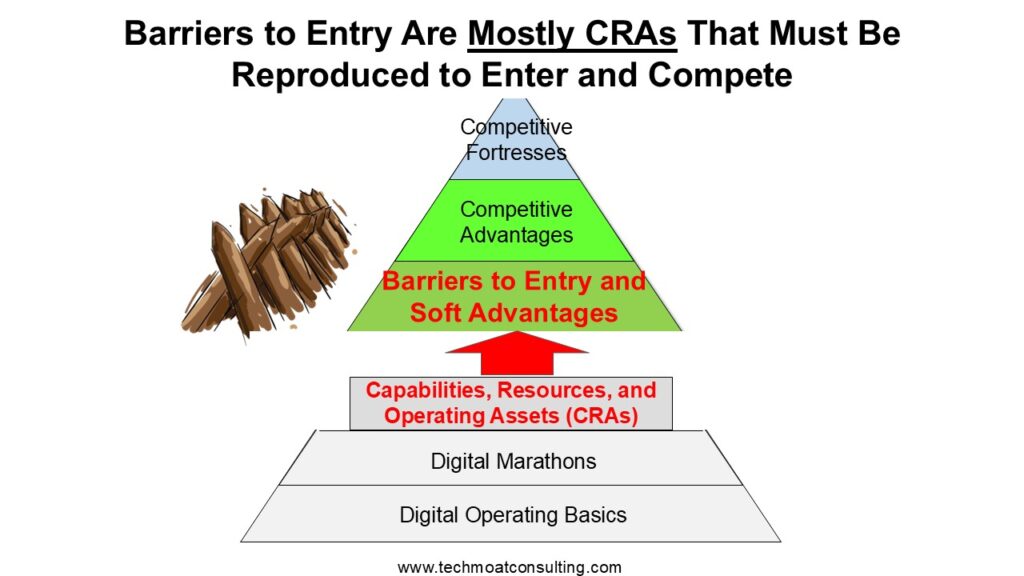

I define Barriers to Entry as mostly the CRAs that as well-run business must reproduce to enter and compete.

I am looking for structural advantages (i.e., moats) that manifest from operating activities and operating assets. For barriers to entry, that means identifying the key capabilities, resources and operating assets (CRAs).

Barriers to Entry are mostly about reproducing specific CRAs.

This is similar to reproduction valuation, where we list the important assets that must be reproduced to replicate a firm. Which includes a lot of stuff. Everything from tangible assets on the balance sheet (like factories) to intangible assets not on the balance sheet (like IP and customer relationships).

Within this, there are a few specific CRAs that are the key to entering a business and being a viable as a competitor. I identify those specific CRAs. And then I put numbers on them. Specifically, I want to know what is the cost, timing and difficulty to reproduce them?

That is the barrier to entry. Here’s my graphic for that.

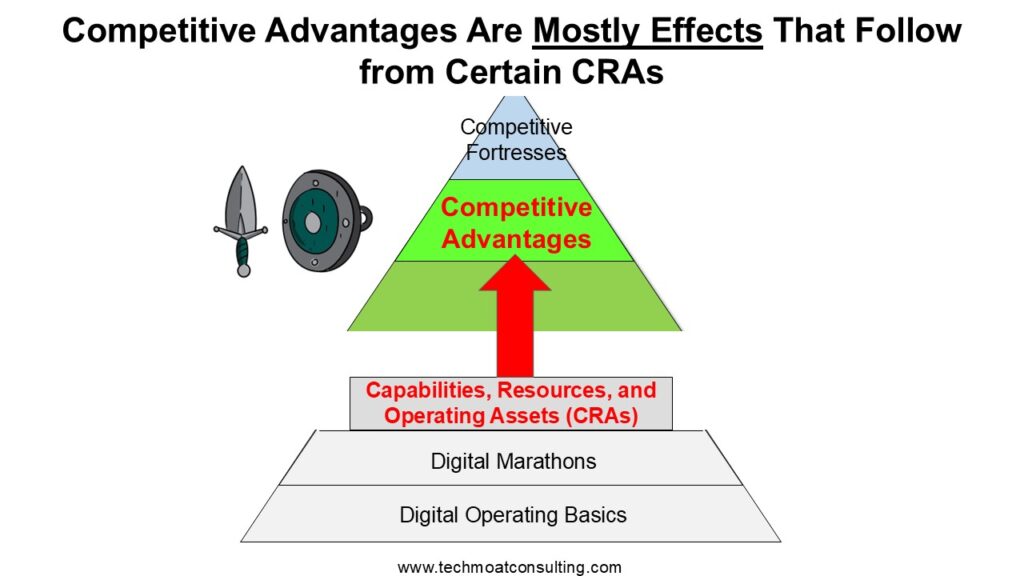

Then I move on to Competitive Advantages, which is about rivals already in your business.

I define Competitive Advantages as mostly effects that put a rival at a revenue or cost disadvantage.

Competitive advantages are not CRAs. They are not assets that must be reproduced. Competitive Advantages are effects that manifest from specific CRAs. This is where we go from a resource-based view of strategy to a micro-economics view.

And I have a list of these.

I identify the key competitive advantages in this list that matter against:

- Larger rivals

- Smaller rivals

- Equally sized rivals.

I really want to know exactly where the advantage is coming from. And I put numbers on them that I can track. This is also helpful for when a new digital tool starts to impact a business. I want to see which competitive advantages are being impact and which aren’t.

That’s my approach. It’s very granular.

Ok. That’s it for today.

Cheers, jeff

——

Related articles:

- 5 Things People Get Wrong about Scale Advantages, Economies of Scale and Moats (Tech Strategy – Podcast 251)

- The Characteristics of Unattractive Industries with Cutthroat Competition (1 of 3) (Tech Strategy)

- 5 Misconceptions About Barriers to Entry (Tech Strategy)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Scale Advantages

- Scale Disadvantages / Diseconomies of Scale / Big Company Disease

- Competitive Advantage: Economies of Scale

- Scale Advantage Cascade

- Capabilities, Resources and Assets (CRAs)

- Porter Five Forces: Buyer Power

- Porter Five Forces: Supplier Power

- Barriers to Entry

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

———

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.