This week’s podcast is about Warren Buffett and combining competitive advantage with compounding.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

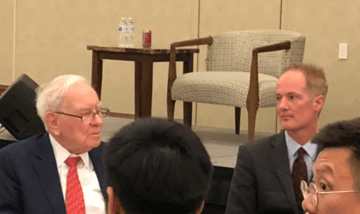

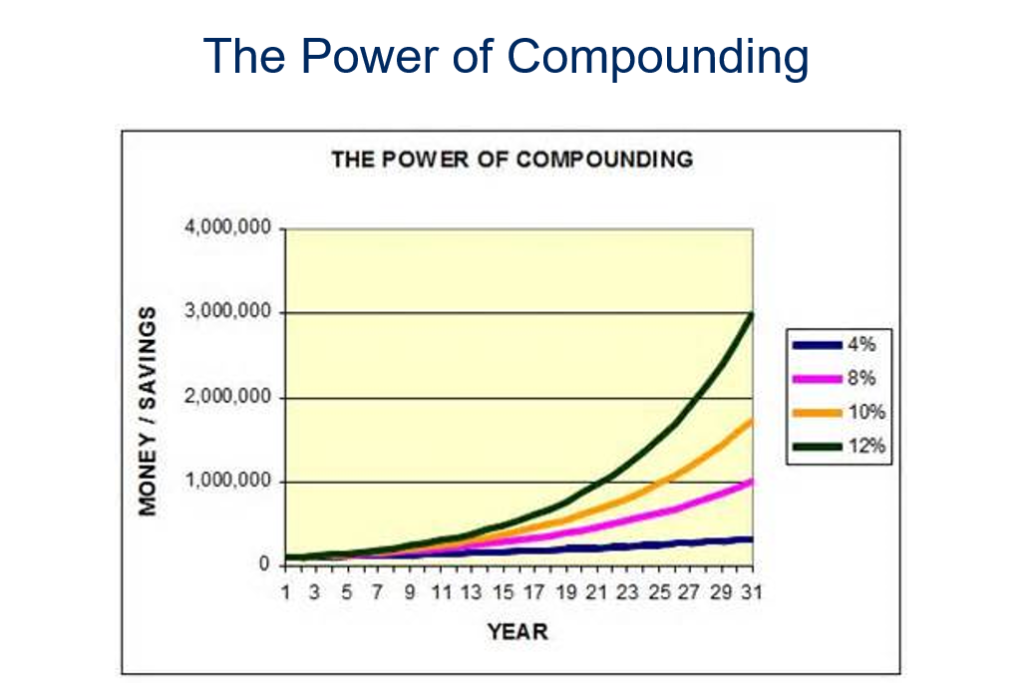

Here are some slides on compounding.

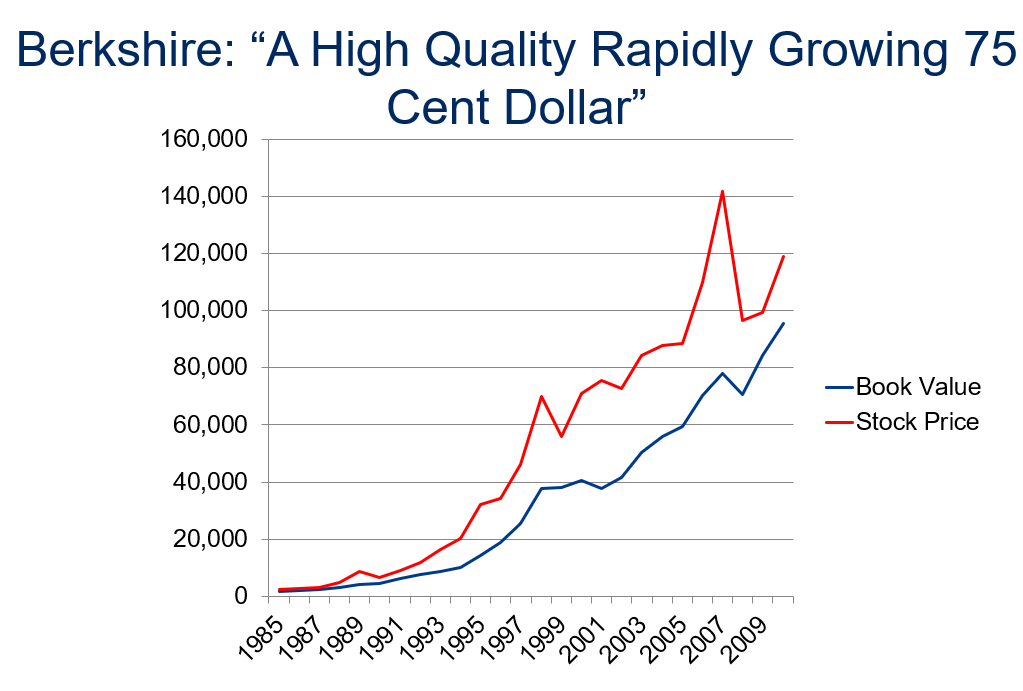

Here are some slides on Buffett’s investment strategy

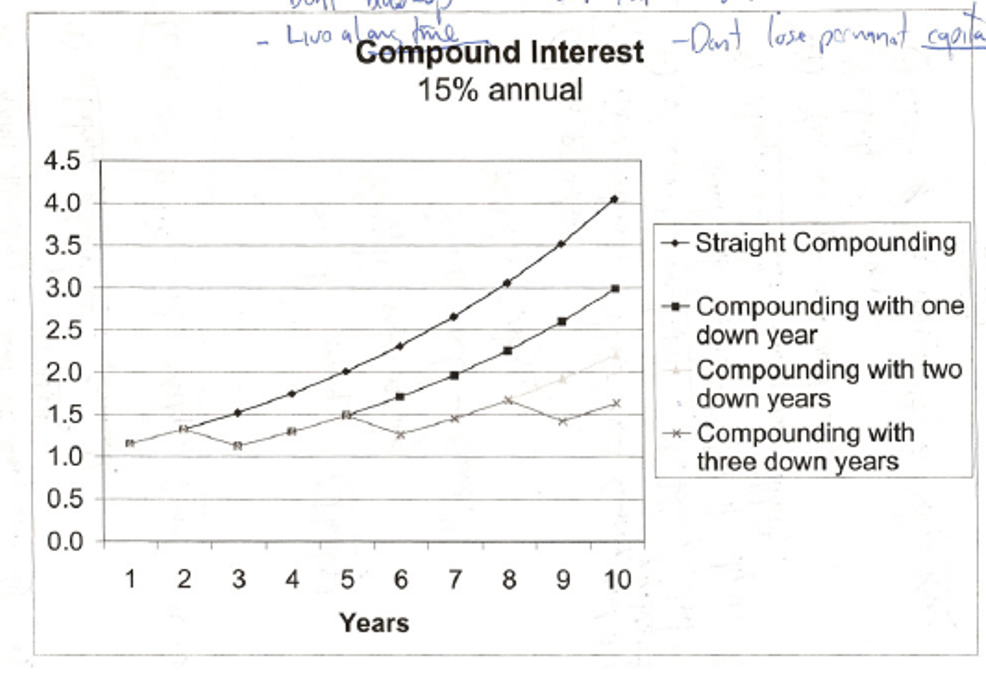

Some fun pictures from Berkshire meeting. Plus my <3 minutes of fame being on the big screen in the Berkshire meeting.

—–—

Related articles:

- I Took 20 Peking University Students to Lunch with Warren Buffett (Again). Here’s What Happened. (Pt 1 of 4)

- 3 Life Lessons from Lunch with Warren Buffett

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Compounding

- Competitive Advantage

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Warren Buffett / Berkshire Hathaway

——-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

—–Transcription Below

:

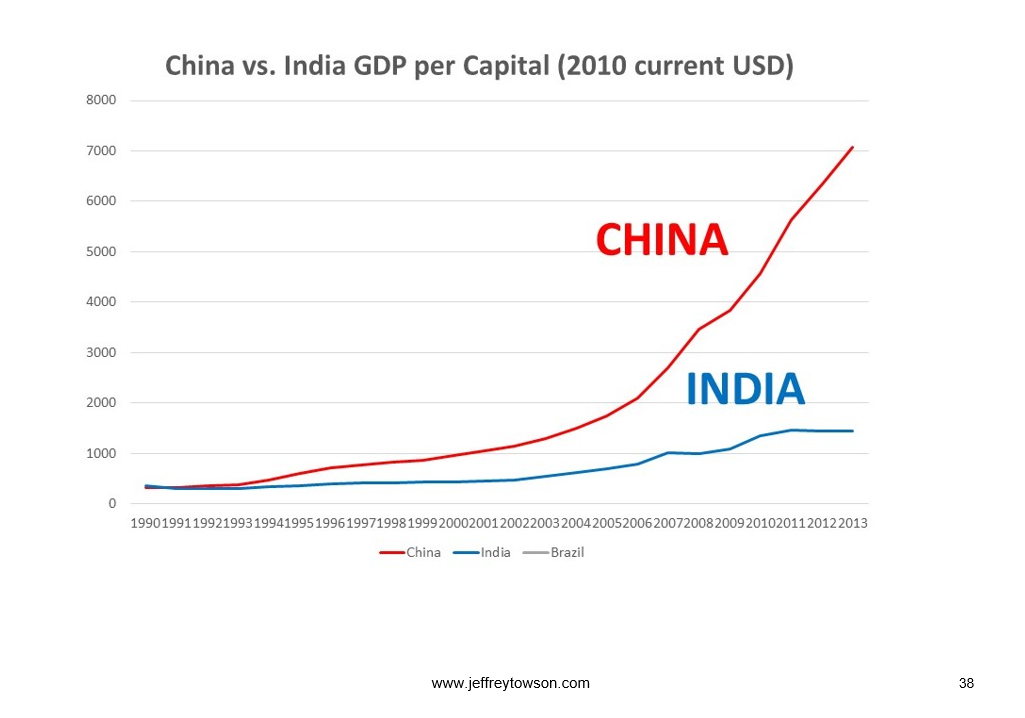

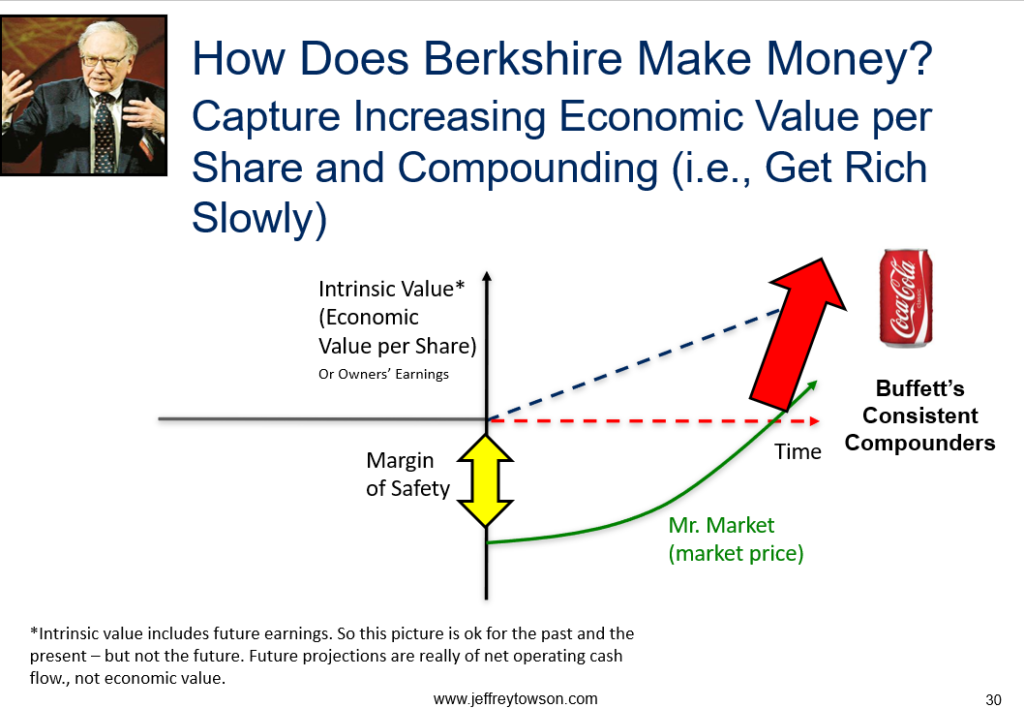

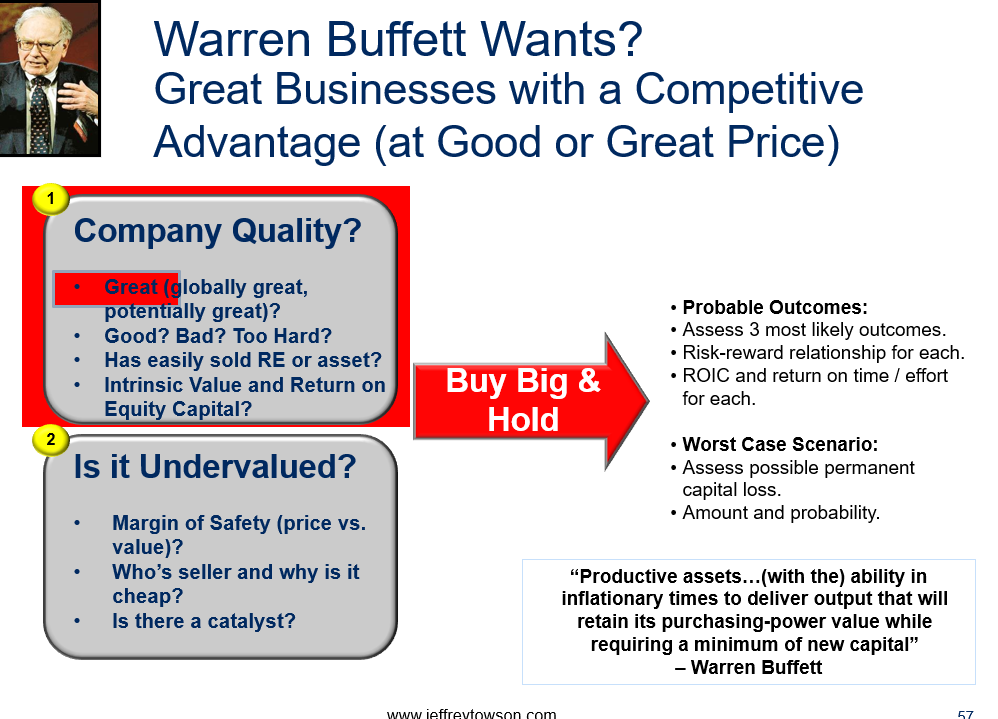

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, lessons from Warren Buffett on compounding and competitive advantage. So I’ve been talking about competitive advantage quite a bit. Competitive advantage meets digital, which is kind of my thing. But I didn’t really ever talk about how certain investors use it differently. the idea of having a barrier, some degree of protection, competitive strength and defensibility, how that can be used in multiple ways. And Buffett has a very clear strategy on how he uses that, which is to combining it with compounding. So I kind of wanted to talk about that as an approach. And then probably in the next week or two, I’ll touch on a couple other investors like Philip Fisher and… Carl Icahn and some others who also use the same ideas, but they use them very, very differently. And I used to teach a class for several years at Peking University, which was called the Legends of Investing, where I would basically go through 15 or so really famous successful investors, like Buffett, Graham, Fisher, Klarman, all of these, really going back 100 years. And it was mainly to sort of emphasize a couple key points. So look, if… There’s a couple important ideas to keep in mind. If you remember the person that made billions off that idea, it’s a lot easier to remember the idea. So for Warren Buffett, my two concepts I would always ask the students about were competitive advantage and compounding. Ben Graham, it was margin of safety, and there was a bunch of them. So that was kind of a good little trick just to remember the idea. So that’ll be kind of the point for today is just how he uses this as an investment strategy. and I’ll go into some of the others maybe in the next week or so. For those of you who are subscribers, I sent you an email a couple days ago about Philip Fisher and how there’s a lot of good lessons for how he used to invest in companies like Motorola for looking at companies like Tencent. How do you determine which company is gonna create product after product for decades? Which is a really interesting sort of qualitative question that he was very good at. So anyways, I sent you a note on that. I’ll probably talk a little bit more about him as a way of thinking about rate of learning, which is another one of the concepts. But yeah, for today, just Buffett, compounding competitive advantage. And I apologize if the audio is a bit strange. I’m doing this from a WeWork in Rio and it’s in one of those little phone booth things. So I think I’m getting a bit of an echo. Hopefully that’s not too annoying. And let’s see, standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guess may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may be incorrect, no longer accurate or relevant. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s just talk about Buffett for a little bit today. Now, for those of you who’ve been listening for a while, you know I’m kind of a Warren Buffett fan boy, which is… a bit strange of a thing to be in life, you know, to be a groupie for a 91 year old man is a bit unusual. But yeah, I mean, it’s, there’s something really interesting about Buffett, which is, one, you can learn an enormous amount. Clearly, you can save a lot of time in life by studying that guy and some others, you know, who’ve been thinking about the same questions forever, you know, might as well take their learning, that’s great. Also, I think there’s something kind of more than that. I think there is a bit of a cultural thing that happens. If you’ve ever been to the Berkshire Hathaway meetings, obviously not in person right now, but if you ever go to one of those, you know, you have 30, 40,000 people all flying to Omaha. And there’s something about that beyond, hey, this is really useful information. There’s something of a cultural phenomenon where the way he speaks, and the way he thinks, I think it appeals to rational minds in a fairly significant way. If you’ve ever gone to one of these meetings, you feel dramatically, well, some of us, you feel dramatically better afterwards. Like, it’s almost like going to church, not to offend anyone who’s Christian, but when I used to go to church, I would always feel better the next day. And there was some feeling like that, where he speaks, I think, very… Cleanly to a rational mind and it seems to resonate a bit I’ve always never been able to put my finger on what exactly is going on but You know when you see forty thousand people fly into Omaha to listen to someone something unusual is happening Beyond the fact of hey, that’s really interesting information But I’ve never really figured that one out. Okay, so The basics of Berkshire, I think you all know, and I’m not gonna go through it because there’s books and everything about that, massive company, hundreds of billions of dollars. If you break it down to the portfolio level, the way I’ve always heard it described and I think is accurate is it’s the Louvre of great businesses. It’s like going to the Louvre in Paris and there’s the Van Gogh and the Picasso, it’s the best of the best. in one building. Even though they’re very different types of artists, they’re all the best at the base. If you look at his companies, it’s the Louvre of great businesses. They are all strong competitive advantage, cash generators, well protected. They’re all very unusual. There’s Geico, and there’s Seas Candy, and Coca-Cola, American Express, Wells Fargo, Dairy Queen, I don’t know, Fruit of the Loom. It’s just a random assortment of companies, but when you take them apart, you all realize they have the same sort of high quality characteristics. Now, one of the things I think people get wrong about that is there are different types of quality businesses. Some businesses, usually the ones I’m talking about are tech companies, which can show sort of spectacular growth. And there are very, very small percentage of businesses that you would put in the truly great category, you know, Google and Amazon and Alibaba. And that was the kind of stuff that Philip Fisher would also go for. He would go for Motorola, these very, very rare, truly spectacular companies that could grow over decades. Okay, that’s mostly not what Buffett’s going at. He’s going at sort of a level down from that. I mean, Coca-Cola is a very good business, but it’s not going up 10X. And it’s not in creating product after product. No, it’s sort of a, what I would call a steady compounder, as opposed to sort of a rocket ship. And I think that speaks to how he looks for competitive advantage. He’s not looking for 10 cents. he’s looking for Seas Candy. Big competitive advantage for sure, well protected, but its primary characteristic is not that it’s gonna grow dramatically, its primary characteristic is it will never go down. This company may win and it may do okay, but it will never lose. He’s in the business of buying the never lose companies because, as I’ll get to in a minute, he’s based on compounding. And the key to compounding wealth is never lose. And I’ll go into sort of why that is. Okay, so when you look at his companies, I’ve listed some of them. Let me see if there’s some more here. Nebraska Furniture Mart, Jordan’s Furniture, Borshams Jewelry, NetJets, Flight Safety, Procter & Gamble, BNSF Railroad. I mean, none of these are 10X companies, although some of them have done well. They’re- They’re more slow, steady growth companies. But not big growth, I mean like three to five percent. Okay, so you look at Berkshire at the portfolio level, good way to think about it, it’s the Louvre of great businesses. You look at it structurally and you can basically see three entities. You have Berkshire Hathaway, the headquarters, which is in Omaha. You can’t miss it if you ever go to Omaha. It’s the only building with 15 or 20 stories. There’s not that many buildings in Omaha. It’s right down the street from his house. He literally, I mean, his house and his office are on the same street, and he just goes down the road five minutes. Last time I checked, it had 24 employees. That’s sort of the entity that really just does one thing, which is capital allocation. I mean, that’s really what they do. And you could argue they’ve replaced CEOs in theory, but they don’t really do that much. They’re in the capital allocation business. The other two entities, they have a bunch of operating companies, that’s an entity, and then they have a bunch of insurance businesses. The insurance businesses, Geico, GENRI, Berkshire, Reinsurance, what’s the purpose of those? One, they’re pretty good businesses. But two, they generate the float. And he uses that float, which he then invests, and he uses that to buy other companies. And the number that Berkshire and Munger say is like 3%. That they’re getting capital by using the float. at around a cost of 3%. And then they invested. Operating companies, retail, consumer, energy, utilities, lots of things. In theory, they get a return on equity of 13%. So you’re getting money at 3% out of your left pocket. You’re investing it in your right pocket. You’re getting 13%. That’s kind of the game. And then in addition, they do kind of a bunch of new acquisitions from time to time. and they also do a lot of bolt-on acquisitions. But that’s kind of how I’ve always drawn it out. That’s a really simplistic explanation. Here’s a quote from Charlie Munger. Quote, we’re like the hedgehog that only knows one big thing. If you can generate float, this is in quotes, cash from insurance premiums that Berkshire can invest before claims must be paid. If you can generate float at 3% and invest it in businesses that generate 13%, that’s a pretty good business, unquote. So kind of what I said. What else? Berkshire, the company he bought that, he began buying Berkshire shares in about 1962. I mean, this was when he spent the first nine years running his partnership, which as far as I can tell was him just sitting at a desk in his house. And he used to buy a bunch of… you know, cigar butt, cigarette butt companies, these sort of bad companies that were dirt cheap that no one wanted, because they were usually dying or on their way. And he would buy them sort of Ben Graham style, and he’d buy them, make a little bit of a margin, and then sell them. And that was his thing. And one of those companies was Berkshire. At the time, he ended up taking it over. The market value of Berkshire was about $18 million. and the shareholders equity on the balance sheet was about 22 million. So, I mean, he was just buying these sort of dying or almost dead companies really cheap, then usually flipping them. In that case he didn’t flip it, he just used it as a shell company to buy their stuff, but they closed down the business pretty quick. Well, over years. Okay, so there’s a bunch of books about all that stuff. I’m not really going to go into that. I want to go into… Why do you do compounding and competitive advantage in this style? What’s the idea? When you look at Buffett, when you look at the types of companies he buys, the standard thing is, oh, he buys great companies. And that’s, you know, he buys great companies at a good price. That’s kind of his standard thing, as opposed to when he was a young guy, he used to buy bad companies at a great price. Now he buys great companies at a pretty good price. Yes and no. Yes and no. I mean the word great is not quite accurate. Typically the companies he’s going to look at, in my opinion as an observer, is something that has a great deal of predictability to it, which is not necessarily the same thing as being great. Highly predictable. What does that mean? Okay so you look at the demand. Something that has a very stable demand floor. The demand may go up, but it’s not gonna go down. Like what? Well, Coca-Cola. Because every human, we know how many human beings there are on the planet. We know that every human being needs to drink liquid every three days or you die. And Coca-Cola sells liquid with some sugar and caffeine and it tastes pretty good. So you could say that’s just a basic needed product. There’s alternatives of course, but it’s not like a discretionary product where people can kind of do it or not. Everyone needs water. The big holding now is the iPhone, Apple. You could argue that there’s a demand floor for having a smartphone. Like if you break your smartphone, how long can you last before you have to get another one? I mean, you basically have to stop what you’re doing that day and go fix that problem because you need another smartphone. Sneakers. things like that, furniture, housing. You know, all these companies he’s in, most of them have a real demand floor, that people just need them, and that makes it kind of predictable. We know how many people there are, we know how many households are gonna be, we kinda know how many dwellings people need, so it’s gonna be owned or rented so he can buy prefabricated housing or something like that. Okay, so that’s the demand picture. And then you look at the technology picture. Well, will tech change disrupt this business or change it? Most of his companies don’t have that problem. Chocolate, soda, even the iPhone is not really disruptable. So kind of not exposed to tech change. And then you get to the big one, which is competitive advantage. Are you protected from your competitors? Cause that can change your destiny faster than just about anything else. and everything he has has some sort of competitive eventually. You can see it’s not really that they’re great businesses it’s that they all create economic value you put one dollar in any of those companies and you’re going to get more than one dollar back over time and that’s called the one dollar test they don’t destroy value and they’re all sort of very well protected and predictable and If you look at my nine questions, I did a podcast a couple months ago about my nine standard investing questions, and the first one is always, is this business attractive and or predictable in the short or long term? So I’m always kind of looking for predictability. And I got that from him. I mean, I copied most of those questions from him and other investors. Okay, but the idea is we are going to see increasing economic value per share of this company, and those are the ones we want. and they’re never gonna go down. So I don’t really call his companies great companies, his Louvre of businesses, I call them the consistent compounders, that they consistently increase value. It may go up more, it may go up less, but it never goes down. which brings us to the other idea for today. I’m not gonna go through competitive advantage, I’ve covered that kind of a lot. The other idea is compounding. So everybody loves compounding, right? I mean, you get 8% per year, you started with 100, then you have $108, then the next year you make 8% of that and you make a little bit more than $8. And you know, the money just keeps going up and up and up. If you consistently make. 8, 10%, 8, 10%, year after year after year, and what you basically get is an exponential. The curve is very, very flat for a long time, like years, like 15 years, and then it starts to sort of increase up and suddenly you’re not talking about a million dollars making 8%, then you’re starting to talk a hundred million dollars making 8%, and 8% of a hundred million dollars is a heck of a lot more. So the curve starts to go vertical. and you get this nice sort of exponential curve, but it takes a long time. And the standard quote is, compounding basically makes time your ally. So you come in with a value-based approach. I’m not gonna speculate. I’m just gonna value this company very strictly. I’m gonna make an assessment, then I’m gonna use time and consistency. And if I do those three things, a value approach, time, and consistency, you will get wealth. It’s almost an ironclad rule. And if you look at Berkshire book value or you look at Berkshire stock price from 1970, 1980 to today, what you basically see is an exponential curve that looks exactly like the curve you get for compounding. And if you look at Warren Buffett’s personal net worth, you see the exact same curve again. I can give you some numbers on that. When he was 39 years old, he had about $25 million. When he was 47 years old, he had $67 million. He was really from that time of 25 to about 49, he was going from about $1 million to $60 million. But then he hits 50 and that exponential part of the curve starts to go vertical. So let’s say age 47, he’s got $67 million. Five years later, $376 million. Five years after that, $2 billion. Five, let’s say eight years after that, $17 billion. So he’s 59 years old, $3.8 billion. Age 66, $17 billion. Age 72, $36 billion. Age 83, $58 billion. It’s that vertical part of the curve. And you can pretty much see it in the stock and the net asset value of Berkshire. And if you just plot out the function as an equation, you’ll see the same curve. You can actually see that same curve at the country level. You can see it in the United States. If you look at GDP per capita from about 1930 to today, you see consistent increasing in GDP per capita year after year, usually just a couple percent. But because it’s been so consistent, the wealth just keeps going up dramatically. And most countries don’t have that. Most countries, they go up a couple, then they go down a couple. If you look at China from about 1990 to today, and you compare it to India, I’ll put a slide in the notes about that chart. You basically see China doing a compounding curve, and you see India not. And it’s dramatic. I mean… 1990 China and India basically had the same GDP per capita. Let’s say $400 GDP per capita in 1990. 2013, India’s up at about $1,500 GDP per capita. China’s at 7,000. Anyways, I’ll post the chart. It’s pretty interesting to look at, but it’s obviously more complicated at the country level, but it’s kind of the same idea. So, you know, people love the idea of compounding that there’s real power to it. And that’s true. But why doesn’t everyone do it? Well, because it’s really, really difficult. Because what does compounding take? Well, it takes a long time, and you can’t make any mistakes. It takes an unbelievable consistency. I’ll put another slide in the notes, which is basically if you compound at 15% per year, you can see the same sort of exponential curve. But what happens if you have a down year? You know, you’re doing pretty good for five years, eight years, and then you have a down year, maybe you’re down 10%. It dramatically impacts the curve. What happens if you have compounding pretty consistently, but you have two down years within 10 to 11 years? It wipes out most of the effect. And if you have three down years, you lose the entire effect. Yeah, Buffett’s been making all this money, but that’s because he doesn’t make mistakes. If you have one or two bad years, you can wipe out the whole effect and you gotta start over. So yeah, it’s unbelievably powerful if you can pull it off. And it’s really difficult. So, you know, the rule for Buffett, his standard statement forever has always been rule number one, never lose money. Rule number two, never forget rule number one. And I think people thought that was just kind of a funny thing to say and it’s how he thinks. I don’t think he’s being glib. I think he’s talking about compounding. The rule number one if you’re going to compound wealth is never ever ever lose money. Because if you lose, the whole effect gets wiped out. And you can work on this for 10, 15, 20 years and do well. You have a couple bad years, it’s over. You got to start over. So if he’s a compounder at heart. and his rule number one is never ever lose what kind of companies do you choose for your portfolio to accomplish that Are you going to choose Tencent? Are you going to choose Tesla? No, you’re going to choose companies that create economic value consistently but have the lowest probability of losing. Which is pretty much kind of what I started explaining, right? It’s got to have a floor for the demand. Everybody needs water. Everybody needs shoes. It needs to have limited exposure to technological change. iPhone and it needs real strong competitive protection. Those are kind of some of the things you look for to get, you know that’s why I said I refer to his companies, not his great companies, but his consistent compounders. They’re the companies that don’t lose. So that’s kind of a different approach to all of this. You know I used to sort of tell students, look if you want to be a Buffett type investor, your goal is not to be smart. In fact you don’t want to be the super smart hedge fund guy. Your goal is to never lose. Your goal is to never be wrong. You don’t have to be right, but you can’t be wrong. Because if you’re wrong, you lose the compounding. If you just have a medium year, it’s fine. So it’s like you’re throwing the dice on the table, and on the dice it has three options, win, lose, or draw. You wanna eliminate the lose from that scenario, and then you just throw the dice all the time, and one of two things happens. You win or you draw, but you never lose. and then you just keep playing that game and if you do that, then time becomes your ally, you compound, there you go. So the goal is not to get rich fast, the goal is to get rich slow. You don’t wanna be the super smart person. You don’t wanna swing for the fence. You don’t wanna make huge returns. You don’t wanna use leverage. You don’t wanna do too much tech. You just wanna not lose, which is really about avoiding things that mess you up. And if you do that, you’ll get rich slowly by compounding, although it takes years and years. So you’re not looking for tech, risk, debt. You’re not looking for 10X, you’re looking for highly predictable companies. And this is why Buffett, you hear him talk all the time, it’s not about being smart, it’s about not doing dumb things. And that’s kind of what him and Munger always talk about, we just try to avoid doing dumb things. So anyways, that’s kind of how I explain Buffett. The Berkshire Company is basically, in my opinion, a compounding machine based on consistency and predictability and never losing. And that’s kind of what I see when I look at his companies. Now that’s most of what I wanted to cover, but I’ll talk about a couple little other things. You know, how do you do… highly predictable returns such that you can compound. Well, I mean, there was early Buffett, which was, as I mentioned, buy and sell cheap stocks. Now, if the company’s cheap, but it’s a piece of garbage, you buy it and you get in cheap because nobody wants it. But then the trick is you gotta get rid of it. You don’t wanna hold on to low quality companies because they go down. So you buy and then you sell. You buy and you sell and you make a percentage. You bought it at 80. you made 20% and you sold that took the returns. The problem with that strategy is you gotta keep finding stuff to buy because you’re compounding at the return level, at the portfolio level. And he did that for a long time and that was kind of Ben Graham’s approach. But you gotta keep finding investments. If you’re not buying and selling, you’re not making any money. You gotta go find more. Time works against you. in terms of holding a particular company, the more, if you’re holding bad companies, time is really not your friend, because things can go wrong. Time is the ally of the great company, the enemy of the mediocre. And generally speaking, bad companies have a lot of problems, and you don’t usually see them all when you first get involved. You kind of discover them. It’s like one bad surprise after the next. Anyway, so 1959, Buffett meets Charlie Munger in Omaha. They meet at a restaurant, start talking, and become lifelong friends. As far as I can tell, Munger was the one who convinced him over time, stop doing this. You don’t want to buy garbage companies and buy and sell and buy and sell. You want to buy a great company and hold it. You want the compounding of wealth not to happen at the portfolio level, but to happen within companies. Coca-Cola itself will compound wealth. They’ll make some money, they’ll reinvest some money, it’ll keep going up, and you don’t have to do anything. So hence, you know, the money is in the buying and holding, not in the buying and selling. Or to quote, here’s a monger quote, if you buy something because it’s undervalued, then you have to think about selling it when it approaches your calculation of its intrinsic value, that’s hard. But if you buy a few great companies, then you can sit on your ass, that’s a crude thing. And he calls it like, sit on your ass investing. And if you view this as a compounding exercise, well, if you have a company that’s compounding wealth in your portfolio, you’re done. You can just sit there and watch it. Here’s another Munger quote, “‘The big money is not in the buying and the selling, “‘but in the waiting.'” One of the interesting things about Buffett, I think, is how central time is to his thinking and his approach. He really seems to think about time as an advantage. that’s something you can take advantage of in terms of returns but also sort of a a counter strategy to how most people invest. He says things that relate to time all the time. Like you make money slowly not quickly. No matter how great of talent or effort some things just take time. This is a quote. You can’t produce a baby in one month by getting nine women pregnant. Another quote, someone is sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree long ago. I think it cuts across all of his thinking in terms of investment and when he takes apart these companies. Another interesting thing about Buffett is everyone talks about how he buys stocks, but he has an interesting strategy for buying private companies, which is kind of like my old boss, the Saudi prince. I mean, he only used to do private deals. And he wasn’t an amazing analyst. He was good, but he wasn’t. like Buffett level in terms of taking apart companies. What he was really good was finding out how to get certain high quality companies from a position of strength. Because if you’re gonna do something in a private deal, usually private deals are pretty appropriately priced. It’s not like the stock market’s swinging around. You’re gonna have bankers on both sides of the table. People are gonna run the numbers. So it’s not like you can wait for a mispricing. What you have to do is you have to be the stronger party in the negotiation. So you have to have leverage, you have to have an advantage, something like that. And my old boss, the prince, he was unbelievably good at finding situations where he could add value and coming to deals of high quality companies from a real position of strength. I think Buffett does this too, in a much more limited fashion when he buys companies. His standard thing, as far as I can tell, is he uses his reputation a lot. you know, when someone sells the company, like the problem with buying great companies privately is they usually don’t need anything. You can buy a lot of busted companies privately because they have a lot of problems and they need money and they need nothing. Great companies usually don’t need anything. They’ve got cash flow, they’re doing well. So what do they need? Well, what happens, I think the scenario he targets is, if someone has built this business over their lifetime and they’re ready to retire, they don’t know what to do with it. It’s their life’s work. They care about it, but what are you going to sell it to a private equity shop that’s going to cut it up and play games with it? You’re going to give it to your kids who might be idiots? So what some people do is they call Berkshire and they call Buffett and they basically hand them their baby and say, this is my life’s work. Would you take care of it? And I think that’s why he has a lot of interesting companies in his portfolio that he’s never sold because I think he promised the owners, I will always take care of your company. So that’s really using your reputation to get into these special companies. I think his reputation plays out another way. If you need it, he can be white knight. If you are in deep trouble, you’re Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, you’re a pretty good company but you screwed up. and you’re on death’s door, if you absolutely have to sell, you have no choice, who do you want to sell to? Well, you might as well sell to Buffett. I mean, you’re in deep trouble anyways, so let’s just call him. So he gets called by companies that need a big cash infusion very quickly. And I mean, if you have to sell, he’s kind of the best person to call. He’s gonna treat you pretty well. He’s not gonna carve you up. So that’s kind of one I think he uses reputation. as a lever to get into deals, private deals. And then large long-term capital appears to be his other, you know, big lever. If you need $10 billion tomorrow, there’s only a couple people who can, one, who have that kind of money, and two, who can make the decision in five hours. He can do it. So he gets those desperate 2 a.m. phone calls for huge money. Here’s a quote from Buffett, we’re now getting two kinds of calls about where people only want us and where people only want cash and fast. We’re the buyer who can come up with cash over a weekend. Anyways, I don’t think people talk that much about how he does private deals and works on that. Okay, that’s pretty much it. Here’s some interesting fun stuff about Buffett. I looked at his schedule once, like how does he spend his days? and he spends most of his day reading, five to six hours a day, mostly financial statements, annual reports. He also reads trade journals, some stock journals. I think he watches the news and reads the newspaper a little bit, but not very much. He says he reads three to four newspapers every day. I think he mostly reads annual reports. He says he assigns a question to himself, kind of like a reporter. You know, a reporter will say, I’m gonna look into this story because I think that company’s cheating. I’ll go do my reporting thing and write on it. I think he assigns himself questions like, is this particular company undervalued? And then he works on it for a couple of days to get to an answer. He spends a decent amount of time networking. It freaks people out apparently, because if you call Berkshire, sometimes he picks up the phone, which is kinda, I know I’ve heard people say that, I don’t know if it’s true. He plays bridge one to two hours per day. Here’s a quote he has. I carried this quote for a long time in my wallet. A quote, I insist on a lot of time being spent almost every day to just sit and think. That is very uncommon in American business. I read and think. So I do more reading and thinking and make less impulse decisions than most people in business. I do it because I like this kind of life. And I kind of… One of the reasons I always remembered that quote and carried it was because I really enjoy that too. That’s like my favorite way to spend my days is to sit with annual reports and a cup of iced coffee and just read, read and think. And I get annoyed when people call me. Like when the phone rings, my immediate reaction is to be annoyed, which is totally stupid. But that’s always my thing. I usually leave my phone at home and I just sit and read for about five to six hours per day. And yeah, it’s logical and yeah, I think it’s helpful, but it’s that last comment he makes. I do it because I like this kind of life. That’s kinda how I feel. It’s just like my favorite thing to do. I don’t know. So fortunately, it works pretty well for a career in investment. Okay, other stuff. What he doesn’t do. He says no very, very quickly. He says no to most everything. I’ve emailed him a couple times and I’ve gotten very polite nos within 24 hours every time. Like if you email his office, you go to his secretary and then She deals with him and then you get an email back either from her or I’ve gotten a couple from him directly which kind of freaked me out. But almost all the time it’s gonna be a very polite no. But you won’t wait, you won’t know, be like oh I pitched this thing, we wanna bring some students out to home on. You won’t have to call back in a week and say, hey did you get that email? No, you send something to the office, you’re gonna get an answer in about 24 hours. Which is very, actually I appreciate that, that’s really helpful. But it’s almost always gonna be no. So he doesn’t do meetings, he doesn’t like to do that, he doesn’t do reports, he doesn’t do Facebook, Twitter, he’s not really on the phone, he’s pretty much not on the online world. They say he doesn’t do email, but I think he sort of does it a little bit with his assistant, I’m not quite sure how he does it. That’s pretty much it, and just sort of a man who of daily habits lives in the same house for, you know. 50, 60 years, works in the same office, eats in the same restaurant, does the same thing day after day. You know, he’s really kind of an interesting dude. I haven’t talked to him in a couple years now. I went out to Omaha several times and brought some students out. And I ended up sitting next to him for, I don’t know, five hours, something like that. And it was crazy, because it was a bunch of students and he really liked students from China, Asia. And we were just sitting, listening to him talk. And there were some other schools there. You know, and it was kind of fun. And then he finishes up and his assistant comes over next to me and puts a can of cherry Coke, like right next to me. And like, I just like did this, wait, what? Wait a minute. Like my brain’s spinning. Like, wait a minute, cherry Coke. Only one person drinks cherry Coke. And it’s sitting, sure enough, two minutes later, he comes over and says, hey, I’m Warren. And I ended up talking first time for about three hours, two and a half hours, something like that. I literally asked him everything I could think of. I didn’t have any more questions. Anyways, I wrote all this up. If you’re curious, go onto my webpage and just search Warren Buffett. And I basically documented all the questions and all the answers and the several days and all of that. I wrote it up in pretty great detail. But if you’re a long time fan boy, that’s pretty, that’s as good as it gets for me. The frustrating thing is there’s no way I can top it now. We could maybe set up a meeting or something. How am I ever going to top that? That was my high water mark. So now I’m just enjoying the memory, I guess. OK, I think that’s it for today. The real concepts I wanted to bring out today was this idea of competitive advantage and compounding. Because competitive advantage can do a lot for you. It can identify predictable companies, or maybe it can identify companies that are declining but not as far as everyone thinks they will. Or maybe it’s a part of a rocket ship type company like a Shopee or something like that. I mean it can play out in different ways depending on your strategy. And when I go into some of these other companies, I’ll see, I mean these are very, very different than a Buffett type company. So consistent compounders, not a bad way to think about it. Anyways, I’ll talk about some of the other investors probably going forward in the next week or two. And that is it for me from Rio de Janeiro. I’ve got another six days here and then I’m starting to head back to Thailand. So it’s been pretty awesome. I mean, I’ve been here about a month. It’s been spectacular. A lot of time in the gym. I’m actually teaching right now, which is weird because this is in Shanghai, but I’m doing it from here, which basically means I had to adjust my sleep schedule 12 hours. So I’m getting up around noon or one and then. I’m sorry, I’m going to sleep around noon, get up around seven, then you sort of get over to the wee work and then I’m there all night long. It’s like me and the security guard from like 9 p.m. until 6 a.m. And then go home, hit the gym, and walk on the beach and then go to sleep. It’s very unusual. Like, I don’t know how people do these midnight shifts. It’s such a strange life. I’ve got two more days of it here with some students and then I’m gonna get myself on the backs onto the normal schedule. Then it’ll be Mexico for a couple of days, back in California for a couple of days, and then we’ll do the trip to Bangkok, which means quarantine and all of that, which is, I don’t know, there’s a lot going on with COVID in Thailand this week. So hopefully that will all work out, but yep, that’ll be it. It’s been a pretty great run. Anyways, I’m gonna try and do this every six months, is choose somewhere to spend about a month. I think this is a good idea. Like, I did this in Japan before COVID. I spent a month. It’s a month in Rio now. I’m thinking I’m gonna do every six months, I’ll choose somewhere and just spend a month living there. Not necessarily touring, just sort of, you know, living life, normal. I really like that. About three to four weeks is about right for me. So anyways, if you have any suggestions for where to go, I’ve been thinking about this. Maybe East Africa for a month, Indonesia for a month. And if you have any suggestions, let me know. The problem is I’m gonna do it, I think, in January. which means winter. So I think I have to go somewhere south. Anyways, any suggestions appreciated. But that is it for me from Rio. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope this was helpful and I will talk to you again next week. Bye bye.