Digital economics are just very strange.

As soon as a service or business becomes infused with software and data technology, the economics start to change and strange things happen. Reproduction costs drop to zero. Stuff starts becoming free. Scalability increases dramatically and can be surprisingly cheap. And some old, obscure ideas in economics start to become important again.

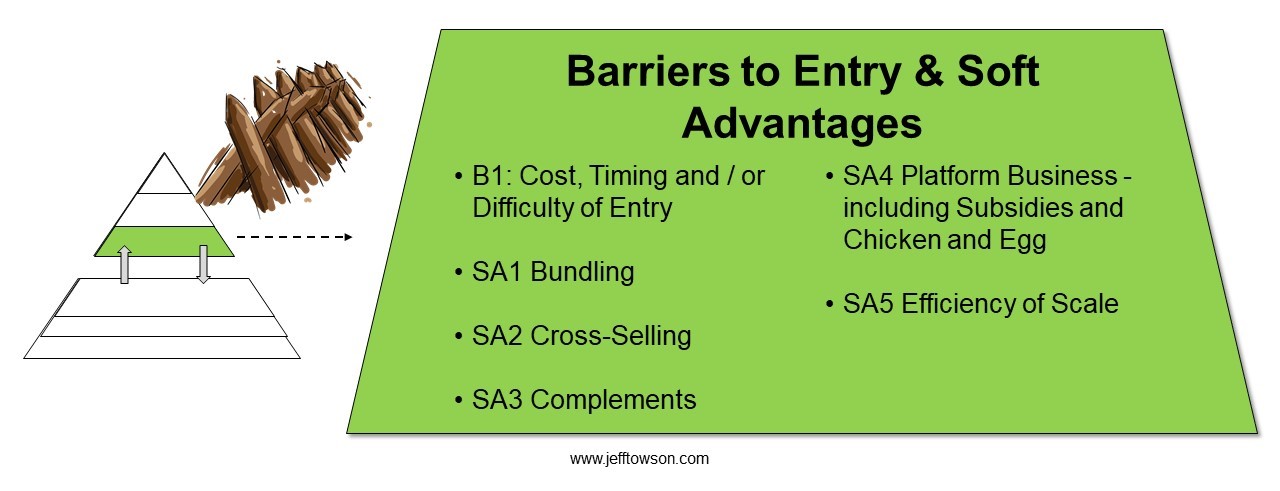

I put these in the category of the “soft advantages” of digital. They aren’t barriers to entry. And they definitely aren’t competitive advantages. But there are common advantages we see in companies that transition to digital economics. And they can be significant. And they are definitely structural, not operating, advantages. I put them in Level 3.

Platform business models is a big one of these. In this article, I will discuss three others:

- SA1 Bundling

- SA2 Cross-Selling

- SA3 Complements

Soft Advantage SA1: Bundling

Bundling physical products is somewhat common and not a big deal. You can buy shampoo and conditioner at the drug store as two items with two prices. Or you can buy them wrapped together as one item with one price. Not a big deal. You can see this type of bundling of physical products in every corner store.

Bundling of services is more common and useful. A barber might cut your hair and trim your beard separately. Or offer both for one price. Services are generally easier to put together in combinations. We see this in B2B all the time, with consulting firms and brokers tiering and bundling their services. A real estate consulting firm may offer a client a market study at a low price. And then try to bundle, or more likely cross-sell, more lucrative brokerage services.

But, as mentioned, bundling and other standard economic ideas get a lot more interesting once you move to digital goods. It is super easy to bundle digital goods, services and information. And on a massive scale

- Digital goods are easy to connect and combine within apps and on websites. It’s often just adding another link or photo on a webpage. As soon as you click on a book on Amazon, it will offer you a bundle with that book and another 1-2 books.

- Digital goods can be bundled at huge scale. Netflix is a bundle of tens of thousands of movies sold for one price. No product or service company can do anything like this.

- Digital economics also means the cost of offering additional digital goods is usually zero. These are non-rival goods with low or zero marginal production costs. So not only is bundling other products easy, you can often do it for free. Why not just offer 3 more digital books to your customer? It costs you nothing as an author.

- Bundling (and cross-selling) digital goods means you can offer big customer surpluses. It often costs nothing to add digital goods to a bundle. And instead of charging for them, you can just give them away for free within a bundle. That creates a big customer surplus, which makes customers happy.

No department store offers bundles of +300 products for one price. But every cable company offers +300 channels for one price. And while consumers like to complain about having to pay for +280 channels they never watch, the truth is cable packages provide big economic benefits for both sellers and buyers. It’s a really good deal on both sides (it’s all about capturing deadweight loss). This is part of how Spotify’s music bundle beat iTunes’s a la cart menu. They bundled hundreds of thousands of songs for one price. And a bundle usually beats a la carte.

So bundles are a good customer offering. And they also have competitive strengths, which is why they are on my list. They can limit competition and create a barrier to entry.

Microsoft put together my favorite bundle of all time, Microsoft Office.

- In the early 1980’s, Microsoft built both Word and Excel in-house. They were originally for Macintosh but were later released on Windows. Word grew rapidly but Excel struggled against Lotus 1-2-3.

- PowerPoint was created from 1984 to 1987 by Robert Gaskins and Dennis Austin at Forethought, Inc. It was released in 1987 and Microsoft acquired it for about $14 million three months later.

Each product sold for about $500 and then Bill Gates bundled all three into Microsoft Office, which sold for about $1,000. He basically gave away one product for free, which was easy since the marginal reproduction cost of digital goods is zero. You can’t do that with physical products and services.

What’s more, Microsoft Office was an integrated digital bundle. That’s even better. The functionality of each product was tied into the functionality of the others. They worked better when you bought all three together.

Microsoft’s competitors almost immediately disappeared, most being unable to go from one to three products to match the bundle. It was a gangster competitive move in terms of value to customers. And the bundle also created a big barrier to entry. Suddenly, any company taking on Office would need to offer three products from day one to be viable. Bundling raises the barrier to entry.

Subscriptions are another type of bundling that can get you a big barrier. As mentioned, Netflix is a big bundle. And yes, Netflix has lots of competitive strengths which are often talked about, such as fairly big economies of scale in both content and purchasing power. But people always forget the barrier to entry from the big Netflix bundle. Before you can offer a competing product to Netflix, you need a library of thousands, if not tens of thousands, of shows and movies. Amazon and Disney+ are both struggling to assemble a big enough content bundle. And most legacy media companies, like CBS and NBC, are not even close to overcoming this barrier. Note: Bundling works best in preference-based goods like media. It doesn’t work as well in commodities.

***

Finally, there is the old joke that there is only two ways to create value in media – bundling and unbundling.

The Spotify example I mentioned is a good example of bundling to create value. However, it was Steve Jobs who had just unbundled music a few years before. The iTunes store broke up the CD bundle. Suddenly, consumers no longer had to buy a CD with 10 songs they didn’t want in order to get the one hit song they did want. Steve Jobs let them buy just the one song for $0.99. The iTunes store unbundled and also dematerialized retail music stores. And yet just a few years later, Spotify disrupted iTunes by re-bundling.

A better explanation for this story is that digital changed the core technology of the music business. That meant first breaking up the bundles on the older technology (i.e., physical CDs) and then re-bundling on the newer technology (i.e., streaming).

Soft Advantage SA2: Cross-Selling

Cross-selling is an everyday business practice.

- You open a checking account and the bank spends the next 5 years trying to cross sell you financial services.

- You order internet service from a cable company and you can’t go 5 days without getting a pitch about adding an entertainment package (also a bundle).

- You try to check out in any retailer and you have to pass candy bars and other low price items at the counter. Note: Price anchoring is also a big part of that.

Physical retailers and banks already have you in the store. So cross-selling is about adding revenues to existing customers.

But revenue is only one part of demand in the digital world. Digital also runs on ongoing customer acquisition, engagement, and retention.

Yes, digital companies want to cross-sell for additional revenue. So, companies like Expedia always try to get you to buy both a plane ticket and a hotel. They make more money on the hotels. So they push bundles. And they try to cross-sell up until your flight takes off.

But digital companies also cross-sell to jump horizontally into other industries. Alibaba jumped into hotels and healthcare by cross-selling to their existing ecommerce customers. TikTok (Douyin in China) used cross-selling to launch their new Xigua app for longer videos. Adding additional services can be very important to staying competitive and keeping user attention. And if you jump horizontally into enough different services, people start calling you a super-app

Sometimes cross-selling services is about launching a new platform business model. Alibaba and Meituan used this to create platforms in hotel services. In this case, seeding the platform and getting a critical mass of users and engagement is the objective. Not revenue. This is how Sea Limited jumped from gaming (i.e., Garena) into ecommerce (i.e., Shopee).

Cross selling in digital is usually more about growing engagement and attention. Plus, this helps gather more data. I frequently refer to “revenue and demand” side advantages. Because demand without revenue is an important part of digital. You can even create entire business lines that are unprofitable but popular to get usage. Then you cross-sell other businesses that are infrequently used but profitable.

We see this at companies like Meituan. It offers bicycle rentals and food delivery, neither of which are especially profitable. But they are popular and get lots of user engagement. Meituan also offers movie ticket purchases, beauty treatments and other smaller services. But it is the hotel reservations and restaurant reservations that are more profitable. This “suite of local services” approach, based on cross-selling profitable vs. popular services, has been particularly effective against more focused competitors like Ctrip and Expedia.

There is an important idea here, which is the expansion of value provided to customers beyond transactions.

For most businesses, the interaction with a customer is mostly a transaction. You walk into a Nike store to see and buy shoes. The store, staff and activities are all about this transaction. But digital goods, with their low marginal production costs, enable businesses to provide far more value than just a transaction. They can offer content. They can offer community. They can offer additional services. And they can do these without requiring any sort of transaction or monetization. The transaction becomes a smaller part of the overall relationship.

Nike China is an outstanding example of this. It offers the Nike Running Club app, which has training programs for members. Nike China also has running events in lots of cities. It has an active running community. It turns out people who run really love running. So Nike offers lots of value to these customers. And mostly for free. It then monetizes by selling them sneakers from time to time. But the relationship and value created is far beyond just a shoe transaction. It is a powerful move. But this requires an ability to cross-sell and continually expand the service offering.

Overall, cross-selling can result in several softer structural advantages:

- Lower customer acquisition, engagement, and retention costs.

- Shared data about customer behavior.

- The ability to expand to a suite of services, which is often a mix of “profit products” and “engagement products”.

- The ability to seed and launch a platform business model.

- The ability to expand the value provided to the customer beyond just a transaction.

Soft Advantage SA3: Complements

Ok. Last one.

Complements is an old school, economics idea that has become really important in digital. So important that Michael Porter added complementors as a sixth force for his five forces.

A complementary good or service increases the value of another good or service. For physical goods, the standard example is how buns are complements for hotdogs. Buns (and mustard) add value to the hot dogs. If the price of hotdogs drops, you get an increase in sales of both hotdogs and buns.

You can consider these complementary products. Or you can consider them as parts of a more complete customer solution. Nobody really wants hotdogs without a bun anyways. We can see lots of examples of complementors in physical goods and services.

- Fertilizer and seeds.

- Blades and razors.

- Appliances and electricity.

- Train stops and railroads.

And in these, you generally see the following economic sequence play out:

- When the price of a complement goes down, the demand curve for the product shifts right (i.e., you sell more buns at the same price when the price of hot dogs drops).

- This increases the customer surplus. The total price has decreased versus the willingness to pay.

- There is a decrease in the number of buyers not willing to pay.

- Overall, the product revenue increases.

However, this really depends on who is the product and who is the complement. If you are the product, you want the complements to drop in price. And your product price to stay the same. But the complements want the exact opposite to happen. It can be a strange relationship.

Generally, one complement is stronger than the other. And the stronger one tries to commoditize and drop the price of all the complements. The counter strategy of a weaker complement is to try to be a highly differentiated complement for a low-cost product that is frequently bought.

Once again, digital economics makes this much more powerful.

Ok. Let’s apply digital one last time.

The economics of digital / information (highly scalable, non-rival, zero marginal costs, low distribution costs) means you can give away complements for free. And you can give away lots and lots of them. This can really increase the value of the core product. If you are a user of Dropbox, you are always being offered additional services for free. If you are on Facebook, you are getting lots of digital content, usually for free. Facebook has commoditized news, which are its complementors. This has been brutal for news outlets.

Smart products are betting big on digital complements.

You can view the iPhone as a physical good with millions of digital complements. You can pay for some of them in the App Store but most are free (the clock, the browser, the flashlight function, etc.). That is pretty fantastic. Apple has pretty much set the strategy for selling a quality piece of hardware with a good user experience and then loading it up with free complements. Most companies going from dumb to smart physical products are doing versions of this strategy. Refrigerators are becoming smart and trying to add lots of digital complements. Same with Smart TVs. Same with smart clothes. Smart toothbrushes. Even smart underwear, which is a real thing.

If you go to any of the big consumer electronics conferences, you will see makers of durable goods trying to become digital and smart as fast as they can. This means adding digital complements, which they or may not try to charge for. For example, here is the LG smart refrigerator. You can see all the functions they are adding.

My favorite function was the button that makes the door transparent. So no need to open the fridge to see what there is to eat.

Another example. This is the JD smart cart for use in the supermarket. They are adding voice assistants, maps, entertainment and other digital complements to the screen. It is also getting good at following you around by itself.

The problem for most of these companies is they don’t have any meaningful way to differentiate themselves with hardware, which is their area. They can add the same digital complements as everyone else. But the big tech companies (Amazon, Google, Alibaba, etc.) are going after control of these complements and operating systems. Hardware makers (televisions, refrigerator, washing machines, temperature control) are trying to differentiate their products but many are being commoditized. And there is a lot of pressure to drop the price of the hardware. You can see that in the budget electric carts being developed.

I thought this company at CES in Las Vegas was differentiating the hardware pretty effectively.

***

Final Thoughts

Overall, a small number of soft advantages do occasionally rise to the level of a structural advantage. It’s a judgement call as to when they are significant and/or durable. But bundles, cross-selling and complements are on my list of soft advantages at the moment.

Ok. That’s just some theory for today, Cheers, jeff

——–

Related articles:

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Bundling and Cross-Selling

- Integrated Bundles

- Complements

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

————

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.