Network effects are like the siren song of the digital world. Everyone wants them. They get lured by them.

But they’re often oversimplified and misunderstood.

Let’s clear up six common misconceptions about network effects. And understand their true nature and implications.

1: Network Effects Are Not the Same as Platform Business Models

Network effects are often conflated with platform business models, such as marketplaces (like eBay or Taobao) or audience-builder platforms (like YouTube). However, the two are distinct concepts.

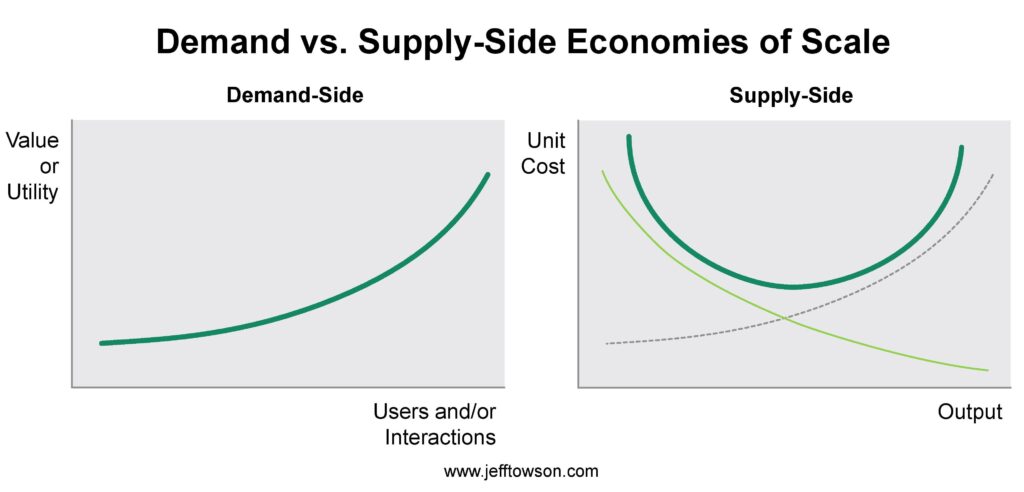

Network effects are a phenomenon where a product or service becomes more valuable to users as more people use it. This increased value can stem from various factors, including more products and services available, more data aggregation, and an enhanced user experience.

However, keep in mind, we are talking about increased value to customers as an offering. That is not the same as economic value capture by the business.

A platform business model, on the other hand, facilitates interactions between different user groups. This can be:

- Connecting buyers and sellers on a marketplace. Think Taobao.

- Connecting content creators and content consumers (viewers) on an audience builder platform. Think TikTok and YouTube.

- Connecting app developers with operating system users on an innovation platform. Think Windows and iOS.

While platforms can sometimes have network effects, they are not inherently dependent on them. And some platforms have weak or non-existent network effects. Additionally, network effects can also exist outside of platform business models. They exist on connected networks.

For example, consider a messaging app like WhatsApp. Its core value lies in its ability to connect people, creating a direct network effect where each new user increases the value for existing users. However, this service and its network effect are not tied to a specific platform business model. WhatsApp could operate as a standalone messaging service or be integrated into a larger platform with multiple services, without altering the fundamental nature of its network effect.

2: Network Effects Are Not Exponential for Very Long

Another common misconception is that network effects lead to exponential growth in users and/or customer value. This often stems from misinterpreting Metcalfe’s “Law,” which suggests that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users. This is how network effects (demand-side economies of scale) are often presented.

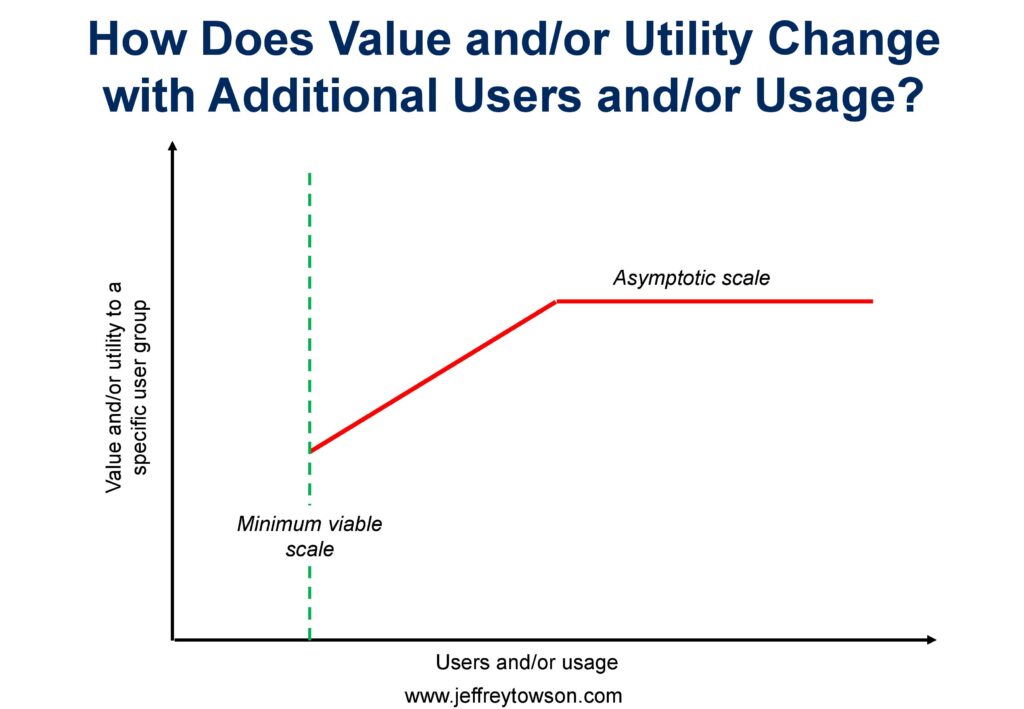

While exponential growth (in users and/or value) can occur in the early stages of a network effect, it is usually quite limited.

The reality is that most network effects are S curves and reach a plateau or asymptote, where the marginal value of each additional user diminishes.

Think about it:

- Having 10,000 merchants selling batteries on a marketplace isn’t more valuable than having 100. Customers have enough choice.

- Similarly, a ride-sharing service with 100 taxis available in your neighborhood is probably as valuable and efficient as one with 500.

This point of diminishing returns is called asymptotic scale. It’s where the value curve flattens out.

Finally, the shape of the value curve can vary significantly depending on the specific network and the nature of its effects. Some exhibit linear growth (like Airbnb), while others might experience an initial surge followed by a rapid plateau. Understanding this nuance is crucial for accurately assessing the long-term potential of a network effect.

This is how I view network effects.

3: Most Data Advantages Are Not Network Effects

The rise of big data has led to the notion of “data network effects,” where a company’s ability to collect and leverage data creates a competitive advantage. While have more proprietary data than a rival can certainly enhance a product or service, most data advantages don’t qualify as network effects. A company might possess a vast repository of valuable data without it directly translating into increased value for users with increased users or usage.

Consider an insurance company with decades of experience in processing claims. Their extensive database might help them assess risk more accurately, leading to better pricing and better underwriting decisions. However, this advantage mostly stems from the company’s scale in historical and proprietary data, not from a network effect where each new customer directly enhances the value for existing ones.

A true data network effect occurs when the data contributed by each user directly improves the service for other users. Waze, a real-time traffic navigation app, is often cited as an example of this. Users contribute data by reporting traffic incidents, accidents, or speed traps, which enhances the accuracy and value of the service for everyone in real-time.

However, I would argue that Waze’s advantage here stems more from its user base contributing and consuming this data rather than the data itself. I think it’s a platform business model with a network effect from active users.

It is important to carefully analyze the relationship between data, users and their behavior, and value creation.

4: Network Effects Can Be a Double-Edged Sword

Network effects are often touted as a magic bullet for success, but they can also quickly become a liability.

While network effects can create a powerful competitive advantage and accelerate growth, they can work in reverse, leading to a rapid decline in value with decreasing users or usage. This is known as an inverse network effect or a negative feedback loop.

Imagine a payment service experiencing a decline in user base. As fewer consumers use the app, merchants might be less inclined to accept it, further diminishing its value for consumers. This downward spiral can lead to a rapid collapse of the network, highlighting the fragility of network-based businesses. They can fall as fast as they rise.

Businesses heavily reliant on network effects must be vigilant in maintaining user satisfaction, innovating their products or services, and addressing potential threats to their network. Failure to do so can result in a rapid erosion of value and competitive advantage.

5: Don’t Confuse Networks, Platform, and Network Effects

These are three separate things.

- Networks are the underlying assets, which are composed of nodes and linkages. These can be physical networks (roads, railroads), protocol networks (Ethernet, TCP/IP), or people and company networks (social networks, marketplaces).

- Platforms are the business models built using these network assets. These business models enable interactions and facilitate value creation, like marketplaces (Amazon, Taobao), audience-builders (YouTube, TikTok), or payment platforms (Alipay, WeChat Pay).

- Network effects are phenomena where the value and/or utility of the product or service increases with its users and/or usage. They are not synonymous with platforms or networks but emerge from the interplay between them.

It’s crucial to disentangle these concepts to analyze businesses effectively.

For example, the statement “Ant Group’s network effect depends on a sustained innovation marathon” highlights how a company (Ant) leverages a platform business model with strong network effects built on people and company networks to achieve a competitive advantage. However, sustaining this advantage requires continuous innovation to maintain a scale differential and prevent rivals from eroding their market position.

6: Don’t Underestimate the Importance of the Type and Quality of Network Connections

Network effects aren’t solely about the quantity of users or connections. The type, differentiation, and quality of these connections play a crucial role in determining the strength and sustainability of platforms and network effects.

For instance, WhatsApp achieved rapid growth by enabling high value connections. They enabled you to text your family and close friends. Not just lots of people around the world. They achieved this by tapping into pre-existing social networks within users’ contact lists. These close relationships offered greater value compared to connecting with random individuals.

Another example is how highly differentiated suppliers, such as unique accommodations on Airbnb, contribute more to network effects than the undifferentiated supply of drivers on Uber.

The quality and differentiation of these connections directly impact the value proposition of the platform and the strength of the network effects.

***

Ok. that’s it. Hopefully this is helpful.

The main point is that network effects are just one piece of the puzzle in building a successful and sustainable business.

————-

Related articles:

- My 6 Questions for Network Effects. And Its 4 Big Effects. (Tech Strategy – Podcast 225)

- 3 Types of Network Effects (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Questions for Huawei’s CEO, JD & Jingxi, Metcalfe’s Law Is Dumb (Asia Tech Strategy)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Network Effects

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.