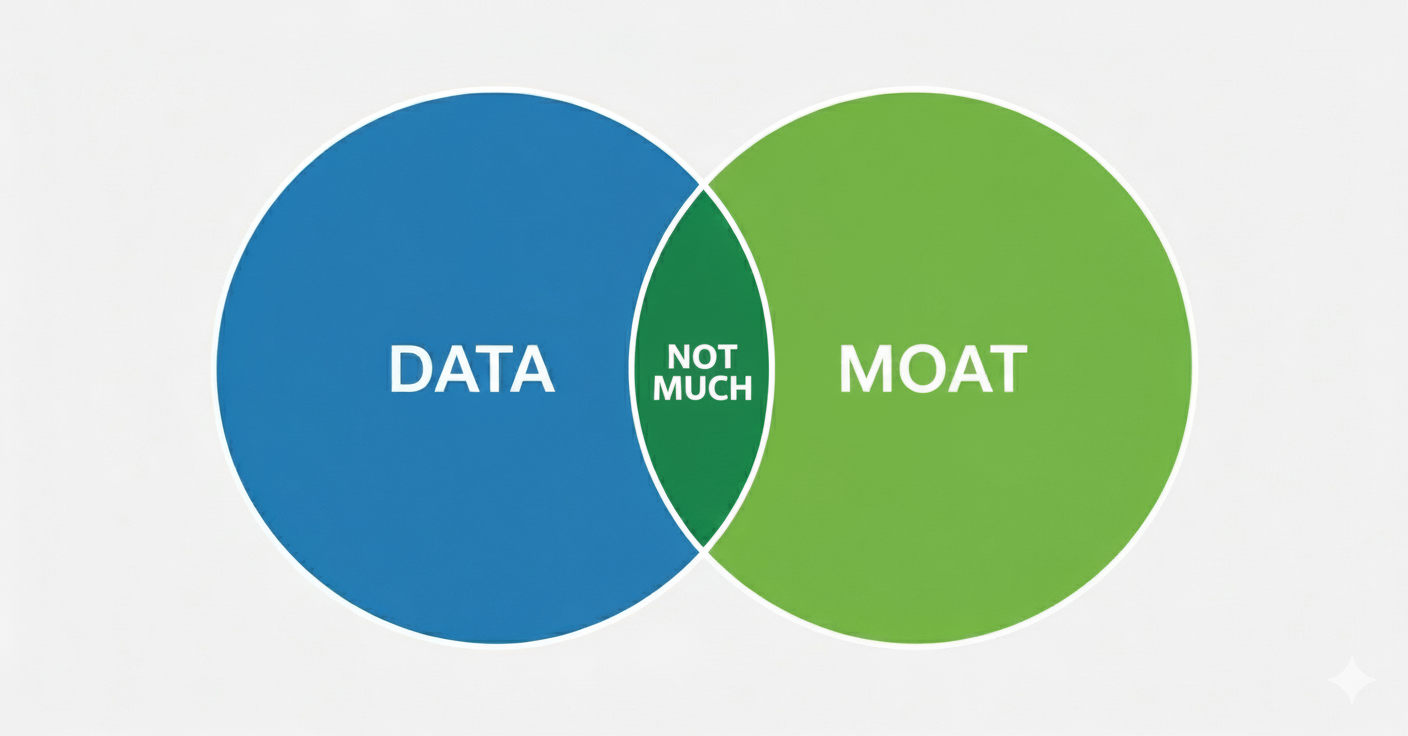

This week’s podcast is about why bundling (and cross-selling and upselling) are so powerful in digital. Plus, some thoughts on why data moats are mostly not real.

You can listen to this podcast here, which has the slides and graphics mentioned. Also available at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is the link to the TechMoat Consulting.

Here is the link to our Tech Tours.

–

Here is the article on bundling by Chris Dixon.

A lot of thinking on data as a moat comes from these articles by Martin Casado, Julian Wright and Andre Hagiu.

- Bundling requires a a robust product suite.

- You want a low attach rate. So you don’t cannibalize products by bundling.

- Bundling can complicate the customer experience and buying journey.

- Bundling works best when all customers have similar total willingness to pay. But different tastes.

- Unlimited bundles (subscriptions) can have problems if there are non-zero product costs.

- Unlimited bundles (subscriptions) do limit revenue per user. This is a problem when willingness to pay is positively correlated with demand for variety.

- Subscription models do not reward superstar creators very well.

———

Related articles:

- How Alibaba.com Re-Ignited Growth with the Alibaba Management Playbook (Tech Strategy – Podcast 253)

- How Amap Beat Baidu Maps. My Summary of the Alibaba Playbook. (Tech Strategy – Podcast 252)

- Scale Advantages Are Key. But Competitive Advantages Are More Specific and Measurable. (Tech Strategy)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Bundling, unbundling and cross-selling

- Rate of Learning and Adaptation

- Competitive Advantage: Scarce or Cornered Resources

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

——–transcript below

Episode 260 – Data NE.1

Jeffrey Towson: [00:00:00] Oh, welcome. Welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy podcast from Tech Moat Consulting. And the topic for today why data network effects and data scale aren’t really moats,, they just aren’t. I’ll go into that plus a little bit on bundling and subscriptions. So, both of these topics have kind of been on my to-do list for almost probably two years where they’re kind of floating in the back of my brain.

Like I, the whole data as an advantage. Data scale, data network effects data as a learning loop. You know, a lot of people talk about, it’s real fuzzy and I kind of always thought like, it’s not quite right. I don’t quite buy it. Lemme try and take it apart. So, I, I think I’ve kind of settled that in my brain now.

And the other one is,, bundling, which. People talk about [00:01:00] all the time, it’s actually kind of more complicated than people think, and I think it’s super important. I think it’s hugely important as a part of strategy, but most of the discussion tends to be a bit shallow. So, I wanted to kind of go deeper into that was kind of my, my to-do list, and I finally got through ’em.

So, I’m going to go through both of those. So, a bit of theory today. With that, let me do my, where’s my standard disclaimer?, nothing in this podcast or my writing or website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guess may be incorrect. Views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate.

Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment, legal or tax advice. Do your own research and let’s get into the topic now, the concepts for today., obviously data network effects, which I think that’s in my concept library. I don’t really believe they exist. In practical terms, but I think it’s on the list data scale effects, which is usually what people are talking about when they talk about data network.

Really. [00:04:00] They’re talking about sort of a scale advantage. I have more data than a rival in the same area, therefore have an advantage. Economies of scale, a scale advantage, that’s usually what people are talking about. So that’s kind of the other concept related to data., and the third one, bundling. Which I usually put that together with sort of bundling, cross-selling and upselling.

I, I put those into one category. If you look on the concept library on the webpage, you’ll see that sort of lumped together., those three things are super important in digital. I mean, it is just really powerful. So that one’s great. Alright, so those are sort of the three concepts for today, which I’ll.

You know, talk about now let’s start with bundling and I’m going to write all this up and I’ll, I’ll send it out to subscribers., but we’ll, we’ll go through the basics here and then I’ll go into more detail. Okay. Bundling, you know, simple idea, it’s been around forever. It was just never that important.

cause when you bundle physical [00:05:00] products. You know, it’s pretty limited. You know, you go into the, the drugstore or whatever and there’s shampoo and there’s conditioner, and you can wrap them together. Shampoo plus conditioner, two separate bottles, you know, wrap ’em in plastic, and then put one price. Okay?

That’s been around forever. Not super important., but the economics of it are, are quite important. Now, bundling, we can do physical products, we can do services and we can do digital goods, which can be content, can be apps, things like that., we’ll start with physical products because I think it’s easier to understand.

The basic idea would be something like this. Okay. Customer A walks into the store and customer A has the key concept here is willingness to pay. A customer will have a willingness to pay for a certain good., we’ll talk about why that’s important. Okay. So, customer A has a willingness to pay, let’s say, $10 for [00:06:00] fancy shampoo as a product, but only a willingness to pay of, say, $6 for conditioner.

So, you add those two things together. This customer, customer a, has a total willingness to pay of $16. If the conditioner six and the shampoo’s 10, that person will pay 16. That’s the total. Now, when you bundle that together, what you might do is you might say, okay, let’s bundle it together and we’ll drop the price.

10% to $15. Now, that’s kind of a win-win. The seller, well, the customer, you know, if you had priced both things at $10, the customer wouldn’t have bought both. They would’ve just bought the shampoo. If you had priced at $6, okay, the total spend would’ve been 12, you probably would’ve taken a hit on your shampoo because, hey, this person would actually pay more.

But if you price it at 15, [00:07:00] which is about, you know, let’s say 10% ish, less than the total willingness to pay of 16. That’s a win-win. The seller sends more or sells more. They got $15 in their pocket. The customer actually does better because they have a consumer surplus, a customer surplus of a dollar.

They actually feel pretty good. They were willing to pay 16, but they only paid 15. They got a customer surplus of a dollar. It’s a win-win. The economics are actually quite good now, let’s say. Another customer comes in and their willingness to pay, their total willingness to pay is also $16, but they’re willing to pay $10 for the conditioner, but only six for the shampoo.

So, it’s the reverse. Now, this is an important scenario. Basically, the total willingness to pay between customer A and B is the same $16, but their preferences. [00:08:00] Is different. One pays 10 for one and six for the other. The other pays the reverse. If you price them both at 10, you’re going to lose half the sales.

If you price them both at six, you’re going to make more sales, but you’re going to lose your premium. If you price them as a bundle at 15, you’re going to sell to A and B at 15. So, two product bundling of a physical good. It’s easy to understand. It’s not super powerful, but when you, one of the reasons is because goods cost money.

There’s a cost of goods sold. Now the other things you can do, you can do this for goods, you can do this for services. Now services, we get a lot more of this good going on., and then when you move to digital goods, the whole thing gets super interesting. But you know, the other thing we could do is we could cross sell.

Hey, here’s the shampoo. Would you like to buy the conditioner today?, $1 off, just the conditioner. That’s not a bundle. [00:09:00] It’s a cross sell. Hey, you bought the smaller shampoo for $10. Would you like to buy the medium for an extra dollar upsell? So upselling, cross-selling, bundling, they all kind of go together.

Uh, McDonald’s does this all the time. Would you like to supervise your fries? You know, would you like to buy this as a meal instead of just the hamburger? Would you like the bundle instead of the thing? Would you like to, you know, we also have an apple pie today. Cross sell. Cross sell, upsell bundle. You can see it all, literally every time you go into a McDonald’s.

Okay, fine. And service companies do this stuff all the time. They sell simple services like, you know, investment bankers or real estate people might sell market studies quite cheap because they’re going to make their money on the transactions. Investment banks used to do this, right? You can buy their research pretty cheap if you’re a client or they give it to you for free because they want your iBanking business.

So, you can tier serve, you can do all these games, right? [00:10:00] Fine. Okay. All of this gets super interesting once you move to digital goods, because digital goods, the marginal production cost is often zero. So, giving away the other good for free doesn’t cost you anything. Well, that opens up a whole lot of possibilities.

Uh, you can bundle things endlessly, you know? Would you like to see this? Read this digital book. You’re on Amazon looking at books. Okay, it’s $6. You could also, they will immediately bundle below. If you buy this book with this book,, we’ll, we’ll do it for you and okay, now they actually have to pay the author in a little bit.

So, there are some costs, but it’s pretty low. But if you go into things like photos,, a lot of videos, articles, you can pretty much bundle at no cost., newsletters that are subscription based, you can bundle them all. The cost, the [00:11:00] marginal cost of production to give away an extra copy of your article is zero apps can kind of do the same thing.

So, it all gets really interesting once you start doing there., and really digital’s awesome for all of this stuff. You can add features; you can create different versions. You can cross sell, you can upsell, you can bundle,, you know, and if you’re aggressive at this stuff. You can basically go after far more parts of the customer solution instead of just trying to sell shampoo, which is one part of a problem.

That’s actually just a small part of the problem. You know, there’s conditioner, there’s shampoo. There’s getting your hair cut. There’s making your hair look good. There’s scalp prob, there’s a whole lot of problems associated with health, hair,, hair care. If it’s digital based, you can go after the whole solution.

You can offer them everything they want. 10 different services, five different compliments. We will solve all your problems for [00:12:00] your trip to Malaysia, hotel, taxi, entertainment, getting dinner. All of that, although it actually turns out it’s pretty hard to bundle,, travel stuff, but generally, yeah, and, and a standard digital strategy, which you’ll see all the time.

This is like standard venture capital 1 0 1 as far as I can tell, is you come up with hot, like sort of a hot new service, like digital payments or messenger. You use that to break into an industry that’s pretty mature. You know, phones,, I don’t know, free email versus traditional email., free digital payments or low-cost digital payments versus traditional credit cards.

At two 3%, you find one sort of hot killer app or service, and that becomes your wedge service. As soon as you break in with the wedge, then you start adding other. Complimentary and other services as fast as you [00:13:00] can, and you basically claim a new part of the value chain., if you read this guy in Singapore, who I, I talk about every now and then, Sanji Cho, Dari, he talks about this as a sort of a, he talks about that particular strategy all the time.

There’s an established value chain. A new technology comes along that creates a new service and reshuffles the value chain. You find a hot service or app that becomes your wedge. You break into a new area, you claim a powerful position, and then you start adding services as much as you can and you rebundle.

So, the first step is sort of unbundling with the new technology. Then you wedge and then you rebundle at the new point. Anyway, you’ll hear that strategy all the time. Okay. There’s a lot there. That’s cool., back to bundling. Now, the standard other example, well really a common example you hear about bundling is,, cable TV packages, 400 channels, 300 channels, [00:14:00] whatever it is now.

And you get it for one price. And you know, they make fun of this. South Park made an episode. Can I just get the channels I want? You know, do I have to buy all 300? Well. If you actually run the numbers like we just did for the shampoo, it turns out cable packages are actually a pretty great deal. It’s a win-win.

And there’s a venture capitalist,, named Chris Dixon. I think he’s Andreessen Horowitz. I’m not sure I’ll put the link in. He wrote a well-known article about the economics of the cable bundle., people use that to talk about bundling, but it, it’s pretty much the example I just said, which is. You know you have someone who wants to buy one channel.

This person loves art or actually not art. Let’s say nature. A nature lover. That’s customer A. He loves art, he wants to get the nature channel, and then there’s a history lover, that’s customer B. This person really wants to get the history channel. Customer B is willing to spend [00:15:00] $10 for the History Channel, but the Nature channel is only worth five or $6 to that person, and the reverse is true.

So, it’s the same package. If you bundle ’em together for $15, a 10% discount from total willingness to pay, you can sell them both channels, same exact scenario. The difference is you can only bundle shampoo with conditioner. You can bundle 300 channels together. And it really works out well. So, the economics of that, you can make the supply and demand curves and basically you’re, you’re capturing more of the willingness to pay under the demand curve.

If you want to get into the details of that, and you can take this further when you start looking at things like the App Store and the iPhone. The iPhone is really a piece of hardware with a couple core services and then massive. Bundle of digital apps and services that most of which you get for free.

You can view the iPhone as a massive digital bundle. [00:16:00] So anyways, you can kind of see in that. And the other example I’ve talked about before is I’ve talked about Netflix. Okay, Netflix, a subscription service. A subscription service is just a bundle. You know, instead of buying each show, you buy all the shows together.

Netflix is massive. Video bundle basically., and one of the things that jumps out about Netflix is you get a really big barrier to entry with a big library. That’s new. I’ll talk about all the value, all the value that comes out of this, but one of the things you start to see is a bundle can start to create a barrier to entry.

It’s very hard for Disney plus to compete with Netflix cause their libraries much smaller. And it’s very hard to replicate a library that is, you know, tens of thousands of mostly terrible shows. But PE turns out people don’t care about that. Another example we’ve talked about in digital is software bundles.

[00:17:00] Microsoft. They’re a bundle player from top to bottom. Adobe’s very good at cross-selling and bundling. A lot of SaaS enterprise software is bundle based., when you look at Microsoft. You can then start to see, ooh, these bundles, apart from having good economics win-win for the buyer and the seller, it turns out they start to create some pretty powerful competitive weapons.

Uh, the software bundle, Microsoft Office, you know, PowerPoint, Excel, word, and you can look at Microsoft Teams, which is pretty much, you know, similar. You know, office 365, the whole enterprise bundle, which is a bunch of productivity tools for the most part. Okay. You definitely get a barrier to entry.

Totally true. You know, when Microsoft Excel bundled with window, not windows, with Word and PowerPoint, and they offered all three of those together as one service [00:18:00] office, you know. The software players that only had Excel or only had a word, couldn’t compete anymore because they couldn’t really get all three.

Created a big barrier to entry. You can build in switching costs to software services in general. You know, if you sign up for Microsoft Teams or you’ve integrated some enterprise software into your business, there’s a switching cost. Well, the switching cost gets a lot more powerful when it’s a bundle, you know?

It’s three times as much., you can do something in software which we don’t see elsewhere, which is you start to get an integrated bundle where if you buy Word and you buy Excel and you buy PowerPoint, they work better because the services integrate. They can start to share data and some other things so you can get software bundles.

This is definitely true for Adobe. If you have an Adobe bundle, you know, for content creation, they work better. Each [00:19:00] product works better when it’s paired with another product than as a standalone. It’s not a huge jump up, but it’s, you know, let’s say 10 or 20%. And the other thing you could start to see is you start to see bundles being used as a weapon.

Um, you know, I just kind of said, look, bundles are a big positive for consumers, customers, which they are. At a certain point, they can turn into a weapon.. And they kind of hurt customers. So, Microsoft does this where they say, hey, you’ve already bought the Microsoft Teams bundle, or you, you know, you bought the enterprise bundle or the office bundle, we’re going to put Microsoft Teams in there for free, which is, you know, a work messenger.

Well, that’s devastating for Slack. And it was absolutely devastating for Slack when Microsoft Teams basically integrated. An identical service into their existing bundle, and they didn’t really charge anymore for it. [00:20:00] It’s kind of a scorched earth strategy to destroy it. And if someone else is, if you’re already buying the Microsoft bundle and they start to put in teams for free, it’s kind of like, I get it for free, or it’s a marginal cost.

Why would I buy Slack at that point? So yeah, you’ll see them do this sort of scorched earth strategy, which is pretty brutal., so at a certain point these bundles sort of go over to the dark side, but generally they’re good for customers, but they can be a, you know, you take away options from customers.

Slack had to basically sell to Salesforce pretty much because of this, in my opinion. Okay. So, there’s a lot going on once you start going bundles into software, digital goods, things like that.. Here’s a, here’s a quick summary, and I’ll write these in the show notes. Why is bundling good for sellers?

Okay, I wrote down five things. Number one, it gets you more revenue. Your sales just went up [00:21:00] because you are eating up more of the total willingness to spend of a particular customer. Number two, it forces you to segment your customers. You have to know that this customer likes nature and this customer likes history.

This customer will pay more for shampoo and this one will pay more for conditioner., you’ll learn a lot from that. It forces you to really understand who is buying your different products, because the bundles have to be specifically constructed for different customer segments, so you know, what are the specific buying tendencies of specific customer segments.

That is very, very helpful. And you may have a theory about that, so you’ve studied it, but when you actually seeing them buying the bundles, then you know for sure. So, it proves to you what your customers care about based on how they respond to bundles., number three, it reduces your costs. You can get economies [00:22:00] of scope offering a lot of variety of things.

You can get some economies of scale. As mentioned, it creates a barrier to entry in some cases. And you can build in higher switching costs, particularly if it’s software., you could also say that it’s,, it’s, it increases convenience. Sometimes the, the Netflix service is a lot about convenience. That’s one of the things they really pitch to customers is convenience.

One service, you pay every month. You get endless shows. You don’t have to think about anything. So there, there’s a, there’s kind of a lot going on with these, and then I guess you could use it as a weapon, but that’s good for sellers, not for buyers., why is it good for the buyers? It’s a better deal. You are getting good value for money,, because you’re basically getting some consumer customer surplus.

Yes, you were willing to pay $16, but you got it for [00:23:00] 15. One, you got what you wanted. Two, you got a discount. That’s good., it naturally increases customization. You’re getting a more customized solution for what you particularly want. It’s a form of tailoring, which is helpful. And as mentioned, it can often play out in terms of convenience.

Yeah, the Netflix subscription, it’s a big bundle and it’s super convenient that that’s valuable to some customers in some situations. Okay. There’s sort of the basics now. Let me jump into seven things I think that are, I’m going to go through these quick, don’t worry. It’s not that long. Seven things I think people are not sort of paying enough attention to.

Within all of this. I just sort of gave you the basic story. Now, for those of you who are subscribers, I’m going to send you this in detail written out, but I’m going to just sort of talk through it here. cause it’s kind of, you know, seven points is a bit., okay. Things to think about. None of [00:24:00] this works if you don’t have a really robust product suite.

You can’t bundle products that are a three out of 10 in the customer’s mind. You know, they’ve got to be, I would say at least a six or a seven., bundling good stuff with good stuff works if you. Schlocky stuff in there, it’s probably a negative. So, you can put these in the buckets of this is a need or a nice to have, a need to have or a nice to have.

Uh, if you bundled a need with something, that’s also a need. I need to have a, I need to have B. You don’t have to offer that much of sort of a, the customer surplus, you know, you, you can kind of capture the value from both. And you’ll do pretty well. That’s a good scenario. Okay. What if it’s a sort of a nice to have?

I don’t need it, but it’s nice to have it. Well, if you’re going to start to bundle a need with something that’s a nice to have, [00:25:00] yeah, you’re going to have to discount it more. You’re going to have to drop the price more, give away more of the surplus. And if you start putting lower quality stuff in their products, it really, this whole thing falls apart.

It doesn’t work., so yeah, that’s number one. You need the, you need a pretty good product suite to begin with., number two, you need sort of what they call a low attach rate, a low attachment rate. You can, you know, you can see the numbers. Here’s a product, a,, shampoo. What percentage of people who bought the shampoo also brought the conditioner?

What is the attachment rate for that second product specifically rated related to the first? Now if it’s high. Ooh. A lot of people who bought the shampoo also bought the conditioner. Okay. Maybe Bundling’s not such a good idea. cause they were going to buy it anyways and I’d rather they spent the 10 for the, you know, whatever the conditioner.

So [00:26:00] if the attachment rate is lower, okay. That’s probably a win-win. You’re, you’re not going to cannibalize. Your core products by bundling them together, you don’t want to do this and lose money, so you kind of want to have a good sense of the attachment rate. That’s pretty easy to measure. But yeah. Yes, you want to sell more, but you don’t want to cannibalize your popular products, so you got to look at a low attachment rate.

You’re probably good to go. The people who like a, normally don’t buy B, so we can bundle it together. We’re not going to hurt ourselves that that person wasn’t going to buy this anyways., number three. You really got to think about, am I over complicating the customer experience or the customer journey?

Netflix leans, I mean, Netflix could bundle all over the place. They could have 20 different bundles. They don’t do that. It’s very simple, it’s very convenient., that’s the experience they want. [00:27:00] Amazon is more aggressive in bundling. Does it take away from the customer experience? Does it make it too complicated?

They generally put the bundles at the bottom. After you’ve already put something into sort your checkout bin, then they may offer it, but they don’t lead with that. When you, when you search for something, the search results show one product. They do not show bundles at the top. So, you got to think about is it going to complicate it?

Is it going to make it annoying? Is it going to make it hard for me to discern what’s really going on here? Now, maybe the customer doesn’t mind, but my data is getting so complicated, I don’t quite know what’s going on anymore. Simplicity, there’s a lot of value and simplicity. That’s number three., number four, the real magic of bundling doesn’t work all the time.

It works in certain scenarios. Kind of your best scenario is when the total willingness to pay [00:28:00] of two different customers is about the same. They just have different tastes. That’s the history channel lover versus the nature channel lover. They are both willing to pay $16. Their willingness to pay total in aggregates the same.

It just sort of happens that. They have different preferences within that. Well, that’s easy cause then I can mix and match and bundle and they all get what they want. This doesn’t work as well when customer A is willing to pay 16 and customer B is willing to pay nine. That’s actually a problem. The magic isn’t as compelling,, when they sell you a cable package.

They start with the idea that most all customers are willing to pay about $110 per month in the us., well, even if they’re not willing to pay, it’s, it’s kind of a monopoly or a duopoly. So, they’ve accepted that that’s what they have to pay. And then you can just have [00:29:00] lots of different variety under that common willingness to pay.

But you know, when different customers are willing to pay more, it, it gets kind of complicated. And for those of you who are subscribers, I’ll put in the show notes an example, or I’ll put in an article I’m going to send you about when you start talking about four or five, six different products with, you know, five or six different customer types.

Um, this all works beautifully if the total willingness to play is about the same. It gets all complicated when that is no longer the case. I’ll show you how that plays out. But yeah, this isn’t awesome all the time. Number five., the unlimited bundle, which is Netflix, is an unlimited bundle. You can watch as much as you want.

Um, that’s problematic if you’re not a purely digital good because suddenly supplying everything to everybody, no matter how much they want, costs you money. [00:30:00] And the famous examples people always talk about are Movie Pass, and there was a gym membership subscription people pushed years ago where if you buy the gym membership, I think it was called Class Pass, if you bought that, you could go to any of these gyms that were in there as much as you wanted.

Well, it turns out that has costs associated. They, that didn’t work out. Unlimited gym sessions didn’t work. I think movie Pass actually went bust because it turns out some people went to the movie all the time. You had to pay the movie theaters. So, if there’s real costs in this stuff, yeah, the unlimited bundle is pretty tricky.

Now, Netflix has an unlimited bundle. But they can write in their contracts with the content owners, let’s say their licensing content. They can, they can sort of put caps in there. You know, we will pay you every time your movie is shown to a user up to this amount. They can cap it., but yeah, that’s kind of,, a [00:31:00] lot of, when, when people were really excited about subscriptions like 10 years ago,, some of them got into trouble in this area.

Um, number six. This one’s I think, kind of important. I mean, when you, when you do a subscription or a bundle kind of, you, you limit your ability to charge more. That’s the big problem with something like a Netflix or these software packages. You know, if it’s just a per user per month, okay, your kind of capped out your revenue just, just got a hard ceiling on it.

And what you want to ask is, is the willingness to pay correlated with a demand for variety. For example, if it turns out people will pay more, if you have more movies [00:32:00] available they can watch, then Netflix made a mistake by capping it. Because they could have charged people more who want to see more, right?

Oh, you want to have 10,000 movies available to you, or only an only a thousand. If there is, you know, if your willingness to pay goes up with your demand for variety, you know, unlimited bundles, subscription models, they’re not a great way to go. The examples I gave you before for bundling. The, you know, it was all about the total willingness to pay was about the same for different customers, you know, with, they like different things, but you know, if you had doubled the amount of variety, doubled the number of shows, things like that,, that model wouldn’t have worked very well.

So, demand for Variety is a bit of a. And I got some of this, I should put the link in here. I got some of those points from an article, which was pretty interesting. I’ll put the link in. But they, they, that was a point they made, I thought, which was good., [00:33:00] I’ll, I’ll put the link in who that was and give them credit.

Uh, anyways, last point. The whole subscription and bundling thing is a problematic when you have sort of superstar creators or hit shows or anything that’s a, you know. If you have a real hot product, you know, a really popular TV show, a really super app, do you really want to bundle it? I mean, you, you, you just sort of killed your ability to really premium charge for that one thing.

If you got a bunch of mediocre TV and movies on a Netflix, you could bundle all of those. Do you really want to put in Game of Thrones there in the bundle? Probably not So. You know when you get a hot thing, you really don’t want to probably bundle it at all if you can avoid it. Okay. And that’s kind of most of what I wanted to cover on this subject.

There’s a lot going on there. This is one of those areas that’s really worth becoming an expert in. Bundling, [00:34:00] cross-selling, upselling, crosser, all of this stuff. Complimentary services and digital lets you do this, not just internally, hey, we have a bunch of services. But you can partner up with other companies and link those together.

I mean these, this idea of a consumption ecosystem where you have 5, 6, 7, or eight partners and you’re all sort of linking together within one app or one, you can do all of that now. So, there’s a lot of power in this whole position. So, I think about this a lot actually. This is kind of one of my key areas.

Okay. That is, it for bundles, cross-selling, up tilling and all of that. All right. Let me switch over to the other topic of data, network effects, data moats, and all of that. cause, and I’m not, this won’t take long. I’m not going to go through all the details. I’m going to kind of give you my conclusions and yeah.

I’ve been wrestling with this for a long time, and I finally sort of took it apart and say, all right, I kind of know, I, I don’t buy it. I, I don’t buy it., the idea of a data moat, I, I don’t really think that mostly exists. [00:35:00] Data, network effects definitely don’t believe that. Data, economies of scale, data scale advantages, things like that.

I think it’s all starting from the wrong concept, which is data, which is a fuzzy idea. It’s problematic. I think really what we’re talking about is rate of learning. Adaptation and intelligence within businesses. I think that’s what matters in terms of competitive dynamics, I don’t think having data is, is the idea.

I think that feeds into how quickly you can learn as an organization or as a product or as a service, how quickly it can adapt if necessary, how much intelligence gets baked into it over time. That’s difficult to replicate. I think that’s the way you think about it, not data per se. Now I’m working on that bigger idea and I’m, I’m not going to go through that today, but lemma just sort of talk about why I don’t buy the data bit Now.

There’s a book, or sorry, an article written by Martin [00:36:00] Cado, who I think is a, he’s an Andreessen Horowitz guy. Really good thinker., I think his stuff is excellent. He wrote a book called, or not a book, an article called The Empty Promise of Data Moats,, with a guy named Peter Lauten. I’ll put the link in.

Great stuff., I think he’s really a thinker in terms of the economics of generative ai, and he has what, honestly, I don’t have, he’s got visibility into early companies actually building AI tools and seeing their economics. Well, I have to wait for them to go public and they have to be more mature. I don’t do early stage, so I think he sees the numbers.

Okay, here’s kind of my conclusions. Number one, data network effects. I don’t think they exist. People have been talking about it forever. I’ve yet to really see one. Actually, there’s one I can point to. The idea used to be something like this, more data. If you have more data from people using your products and services, you can get better insights. [00:37:00]

If you get better insights, you can then build better products and that will get you more customers. If you get more customers, well, wow, we’re going to get more data. It’s a flywheel. People used to call it sort of a network effect, a flywheel. Well, one that doesn’t make any sense. One, there’s a huge gap in that process.

Like explain to me how you go from better insights to better products. You know, there’s a bit of magic that has to happen there and then from going to better products to better customers, well, that’s not really how the world works. There’s a lot of sales and other stuff. So, this cycle may in fact happen and I, I call this customization and customer improvements, but this is an ongoing operating activity that it can actually take a long time.

It isn’t a flywheel usually., so I just consider, look, this is the ongoing customer improvement process. I think people called in a network effect before they really knew how to describe it. And it’s usually not even a [00:38:00] flywheel, it’s usually just an operating activity. Okay. Now is there a quicker version of that where you can get a flywheel?

Well, yeah, we can get learning loops that are built into certain products like TikTok. As you flick through TikTok, it watches what you do and. Very quickly, it starts to change what you see in your feed. Okay. There’s a process of learning and adaptation and customization and personalization, and the improvements feed directly into the existing product.

It isn’t like some product development process. Okay. I, I would, again, I would just call that customer improvements that you’ve built in a tight learning loop into your process. That’s good. I don’t think it’s a network effect., in fact, I would, I would probably call that a rate of learning,, process, if anything else.

Now, when you get to Google search that one, I think I could maybe be convinced there’s something going on there. [00:39:00] The more people that use it, the smarter it gets, the product itself gets naturally smarter and it becomes better. That’s when I would start to say, okay, we’re not talking about data anymore.

What we’re really talking about is learning and intelligence data is just one input into that process. So, I would, you know, I’ve, I’ve sort of argued that Google search is a learning platform, and I wouldn’t call it a data network effect. I’d call it, if anything, like a learning platform with a, with sort of growing intelligence or a learning, I’d use different words.

So, I don’t really buy that one either. And then the one example maybe you could argue is true is Waymo. A network effect by definition is a network where the interactions between the nodes,, it basically becomes more valuable as a product. The more interactions there are. So, the more people that join Facebook, that’s more nodes and the more interactions they have with other people, more nodes, [00:40:00] the product is itself better.

Okay. Waymo is kind of like that. Waymo’s a, you know, a mapping app that came out of Israel and basically people in their cars put in information and the more people that are using it nodes, the smarter it becomes and okay. You could argue there’s a, a network effect there. I would argue it’s based on learning from the participants of the network, not from the data itself.

Okay. Overall, I don’t think it, the data network effect. Which is would be a type of competitive advantage, a type of moat. I don’t think it exists. I think it’s about learning, adaptation, and intelligence. Let’s go to the next one. The other point people often point to is, well, what about a data scale effect?

You know, a competitive advantage based on scale relative to someone else. Okay. If I have more data, I have a scale advantage. Does that make me better? Does it make my product better? Does it make me cheaper? [00:41:00] Does it make, you know, am I going to see that play out? Does someone with more data have a sustainable, ongoing competitive advantage versus a rival who is smaller in this regard?

Well, I would ask a couple questions there. Does having more data in your data corpus, is that a good thing? And actually, it turns out that’s sometimes true. A lot of times it’s not true. A lot of times when you add more data, you end up adding a bunch of noise and not more signal. Turns out quantity and data is not really the primary thing.

Quality is the main thing, and quality versus quantity of data is actually problematic. Because when you add quantity, almost for sure, your quality’s going to be problematic., and then you have more cleaning and more all of that. So, it’s not clear that having more data has scale advantage is better.

Sometimes it can be. Okay. [00:42:00] Does having data more, you know, having a greater river of data flowing through your system, which is what you need for ai, generative ai, is that better? Is having more data flow coming in? Yeah. Better. Again, kind of,, but you got to think about the quality versus quantity. You got to think about,, the fact that data degrades in value quite quickly.

Uh, you got to think that you can have bias in data. So, the whole scale argument, the, the reason you heard data scale talked about right now is because of Tesla. They say, look, Tesla has more cars on the road. They’re gathering more data. From cars being driven and that is making their driving better. And it turns out that’s true, that there is an initial hurdle to get through, to have really effective autonomous driving until you get to a [00:43:00] sufficient volume of miles driven and recorded,, your driving is not nearly as good and that can create real problems.

So yeah, there is a scale effect. At least in the early stages of this, and I would say that has to, okay. Let’s say it’s true at the beginning of an industry, of a technology being bigger makes your product better. What about in five years from now? I’m, I’m tending to think that this is going to get commoditized and all cars are going to get pretty good.

You know, I think that’s probably going to be happening. So that’s kind of an early mover thing. It’s an early emerging technology thing. You get more data miles that gets you more data that makes your car drive better. You’re on sort of the accelerating part of the curve. But it is going to flatline probably,, maybe not in all cases, but in a lot of cases.

So, yeah, I think that’s mostly what we’re talking about and that is very [00:44:00] different than say a Facebook or something where. If you have more users in your network, it’s just better than a smaller rival permanently. If you’re Coca-Cola, you have larger marketing budget than your smaller rivals permanently.

It’s not an early-stage effect because you are an early mover within soda. Now it’s a permanent competitive advantage based on scale that’s lasted for a hundred and what, 10 years? Something like this. So. Yeah, that’s the thing. Now what I would say is, okay, a co scale advantages probably don’t help you.

Um, in a lot of ways they might., I, I think it is a barrier to entry that to get an autonomous vehicle to drive, well, you do have to get a certain volume of miles and data. So, it is a barrier. I’ll buy that. It’s a barrier to entry., but quality versus quantity is a big problem. And here’s one of the things like.

A lot of [00:45:00] the more data you have, a lot of stuff gets worse. It’s not like having more data is an advantage, it’s sometimes it’s a disadvantage., let’s say, here’s some examples from the Martin Casada article. You know, if you’re doing a call center with generative AI and you want it to answer questions in a chat or something, when it does the basic questions, where’s my package?

Please change my email. It does pretty well. It does pretty well, and you feed it data and it does better. But at a certain point, more data doesn’t really make much difference. The value, the incremental value of additional data starts to drop away in those core questions, the common questions, so it doesn’t help you.

And as you move into more long tail questions,. It turns out the success rate is not great., going [00:46:00] from the core, common questions to the long tail, if you want to expand that way and get more data,, it’s really problematic. It’s hard to, to answer those. Well, and then it also turns out, it usually costs more money.

Uh, so. More and more data seems to get you either problems or decreasing marginal value, and it usually gets you increasing costs. So, this whole idea of having more data, having scale as an ADV advance, it’s not even sure, clear that it’s a good thing in a lot of cases. So, yeah, that’s kind of a problem. So, my conclusion is, look, I think it can be a barrier to entry in some cases, having all this data.

Uh, that can hurt a new entrant. I can also point to scenarios where having proprietary data can actually be a competitive advantage. Consulting actually does this, where, you know, if you have a consulting practice in a certain area, let’s say customer improvements. You can start to generate best [00:47:00] practices because you’ve worked with lots of clients in this one area, and then you can basically turn that into a somewhat of a product where you can go to a client and say, you know, we can compare your performance to best practices in your industry.

Now, in that case, yeah, the data accumulated, which would be proprietary, is actually a real advantage relative to rivals that don’t have that. So, you can turn the data in. If you have proprietary data, you can turn that directly into an advantage as a product itself. That’s another scenario I sort of buy outside of that.

It’s a bit of a question mark. I basically have, let’s see, this is five points, quick points. These are my conclusions. No, I don’t think data network effects exist. I don’t think. Data scale effects really exist. It’s, it’s so fuzzy. It’s hard to know. It’s almost unusable as an idea., most of the differences people are pointing to are sort of [00:48:00] early-stage effects in a new industry.

Okay. However, I do think data can be a barrier to entry in a lot of situations. That’s, that can be useful. I do think that it can be a scarce resource. We would call that proprietary data, but if you look at my competitive advantages list, scarce resource is one of the main competitive advantages. That’s the consulting example.

So, it’s a barrier to entry. It can be a scarce resource sometimes,, I think when you put data and digital services directly within products. Which consulting, you’re basically using data as a product, a service that can actually have some power to it. I think when you add a digital service to a good, like,, you know, electric drills, which you sell, I Dunno, to factories, and now you start to have a data service within those goods and you can [00:49:00] buy the service to check its maintenance at all times.

That’s compelling. So, data within a specific good. You know, sort of a digital data service that is paired with a sold good, like a tractor. That can be compelling. But really the real question here, which is the one I’m trying to figure out is how do you improve your operating performance with data enabled learning?

That’s really, I think, the question that’s at the center of all of this. How can I use data enabled learning to improve parts of my business? My marketing, my customer service, my factory operations, my, my decision making by management, and even in some cases, my products, if I’ve directly baked that into the product, like a tractor that has a digital maintenance service built into it.

That really, to me is the key question that’s in all of this, and that’s the one I’m trying to sort of answer. [00:50:00] If you’ve read all my moats and marathons books, you’ll know I kind of, I brought that up a lot of times and I didn’t really have an answer to it. It is data enabled learning a competitive advantage.

I put it on the list with a question mark. Is it an operating sort of marathon, like a smile marathon? I put it there as a question mark. I think it’s definitely a digital operating basic. I think it’s there. I think it can be effective tactic, so I’m kind of baking it into all levels of my frameworks, but I haven’t really answered that big question of when does it rise to the level of a competitive advantage?

I am getting close, but I’m waiting for more case studies because this is all theory until I can point to companies, you know, that have had this working for five years, 10 years, you know, it’s hard to say. So that’s what I’m kind of waiting for. Anyways, that was a whole lot of theory for today. If you’ve got through all of that, that’s impressive.

I’ll, I’ll write it up in the, the subscriber emails are going out in [00:51:00] detail and I’ll put some of it in the show notes, but. You know, my takeaway would be, yeah, it’s worth spending the time to dig into bundles and cross-selling, to really understand that at a deep level, I think is really valuable., the other one, okay.

You know, the, the net conclusion of the other stuff is all this data talk people talk. I think you can ignore 80% of. Just think about proprietary data, think about barrier to entry, and maybe put in the back of your brain that there’s a question on the horizon about data enabled learning as an operating activity.

Uh, that’s going to be powerful, but that’s sort of a floating question at this point, that that’s the easy takeaway. You can kind of ignore the rest if you want, but if you’re into it, go into it. It’s really an interesting subject, I think. And that is the content for two days. Anyways, that was fun., let’s see.

As for me, I’m, I’m doing well. It, it’s been a really great, great week. I’m, I’m heading out to the Philippines in a couple days. Gona be there for a [00:52:00] bit,, company meetings, maybe take a little break. I try to do like water activities when I’m there. I really enjoy that, but probably not a long trip this time.

And then it’s off to Tencent for their meetings. I’m going to interview a couple of their executives. Huawei as well, probably as well. Huawei Connect is the big conference in Shanghai, which is spectacular. Going to be there. Yeah, it’s going to be a great month. So anyways, that is it for me. I hope everyone is doing well, and I’ll talk to you next week.

Bye-bye.

——-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.