There are a lot of interesting ecommerce plays at the intersection of food and on-demand services. Meituan, GoJek, Grab and Dingdong to name a few. I recently wrote about how Dingdong was doing on-demand fresh produce as a specialty ecommerce play.

- Dingdong vs. Oriental Trading: How to Spot the Specialty Ecommerce Winners (1 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Dingdong and 5 Questions for Assessing Specialty Ecommerce Companies (2 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

I came up with 5 questions for assessing the viability of a specialty ecommerce company – against the big tech giants.

- Is the company sufficiently differentiated in the user experience?

- Can the company compete and/or differentiate in logistics or infrastructure without ongoing spending?

- Does the company have a strong competitive advantage in a circumscribed market?

- Is there a clear path to significant operational cash flow?

- Has the company avoided markets and situations that are attractive or strategic for the major ecommerce companies?

Here’s how I think about this as a strategy question.

I’m basically arguing that specialty ecommerce is mostly a demand-side game where you have to differentiate or avoid the big tech companies. Infrastructure is necessary but specialty plays live and die with their strength in terms of user experience.

Which brings me to Germany-based Delivery Hero, an interesting multinational doing restaurant and supermarket, on-demand ecommerce. So another specialty ecommerce play. Note: In Thailand, it goes under the brand Foodpanda.

Intro to Delivery Hero / Foodpanda

Delivery Hero (DH) was co-founded in 2011 by Niklas Ostberg (and others). It is a pretty standard marketplace platform that connects restaurants and consumers. And as a business model, that is a nice differentiated and local marketplace. As the company developed, it expanded from mostly software doing the interactions to also having a fleet of in-house (and contract) delivery riders. So it is software plus significant physical operations in food. Just like Grab, GoJek and UberEats.

It is specialty ecommerce for on-demand food. And the company has been expanding within this user space. From restaurants to supermarkets and convenience stores. And now to cloud kitchens and “quick commerce” – which is a retailer play for small batch food orders delivered within 15 minutes.

But here is where Delivery Hero is different.

It has been focused on being a multinational from day one. I don’t think I have ever seen a start-up with such aggressive M&A this early on. The company is going for scale by expanding into lots of small countries and markets internationally.

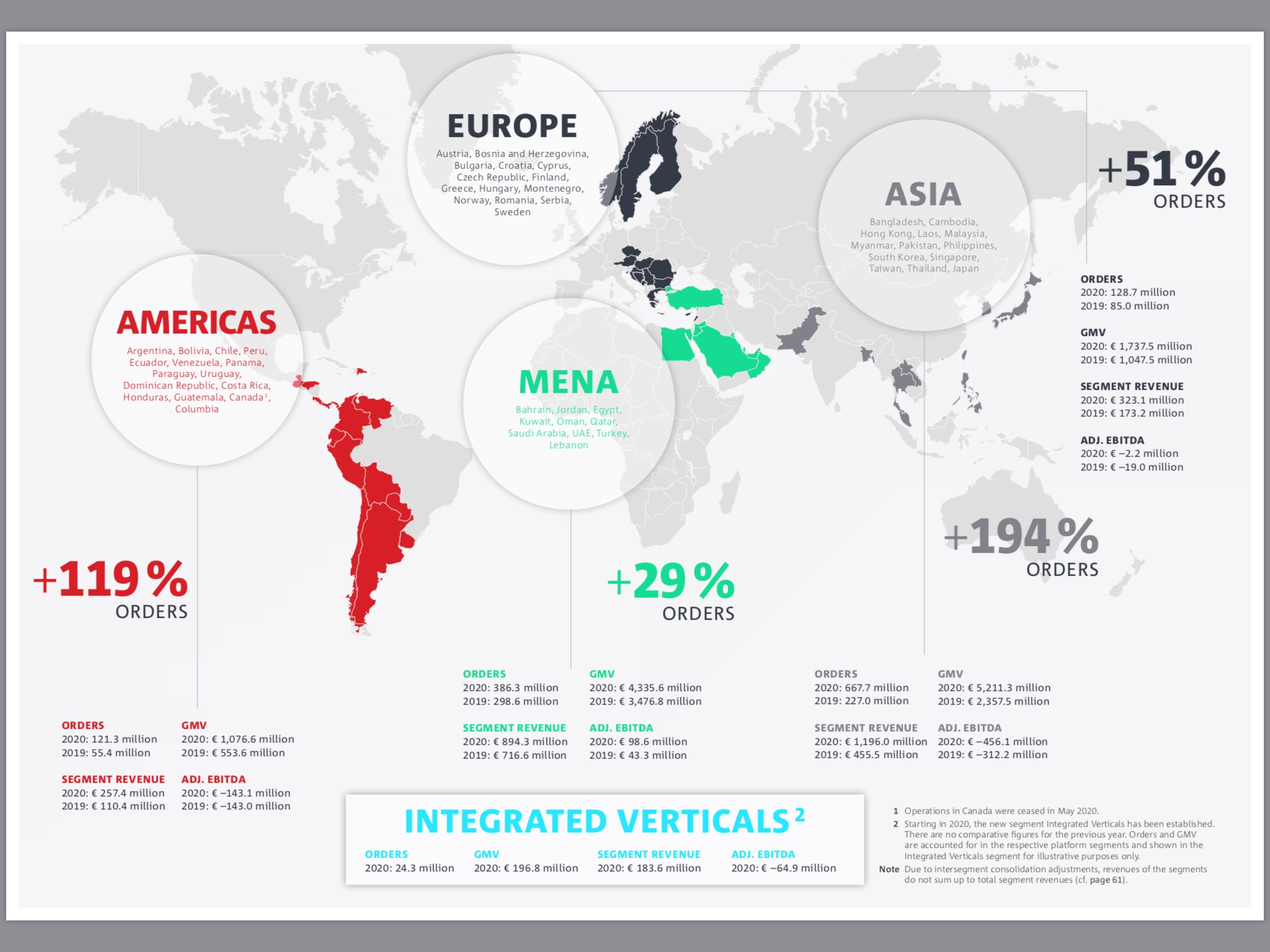

Today, the company is in +50 countries, including Europe, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. It connects with +500,000 restaurants. From the 2020 annual report, here is their operational footprint.

The company is showing rapid growth by both organic and M&A.

- In 2019, the company processed more than 666 million orders. And this grew +100% in 2020, reaching 1.3B orders.

- GMV increased +60% in 2020.

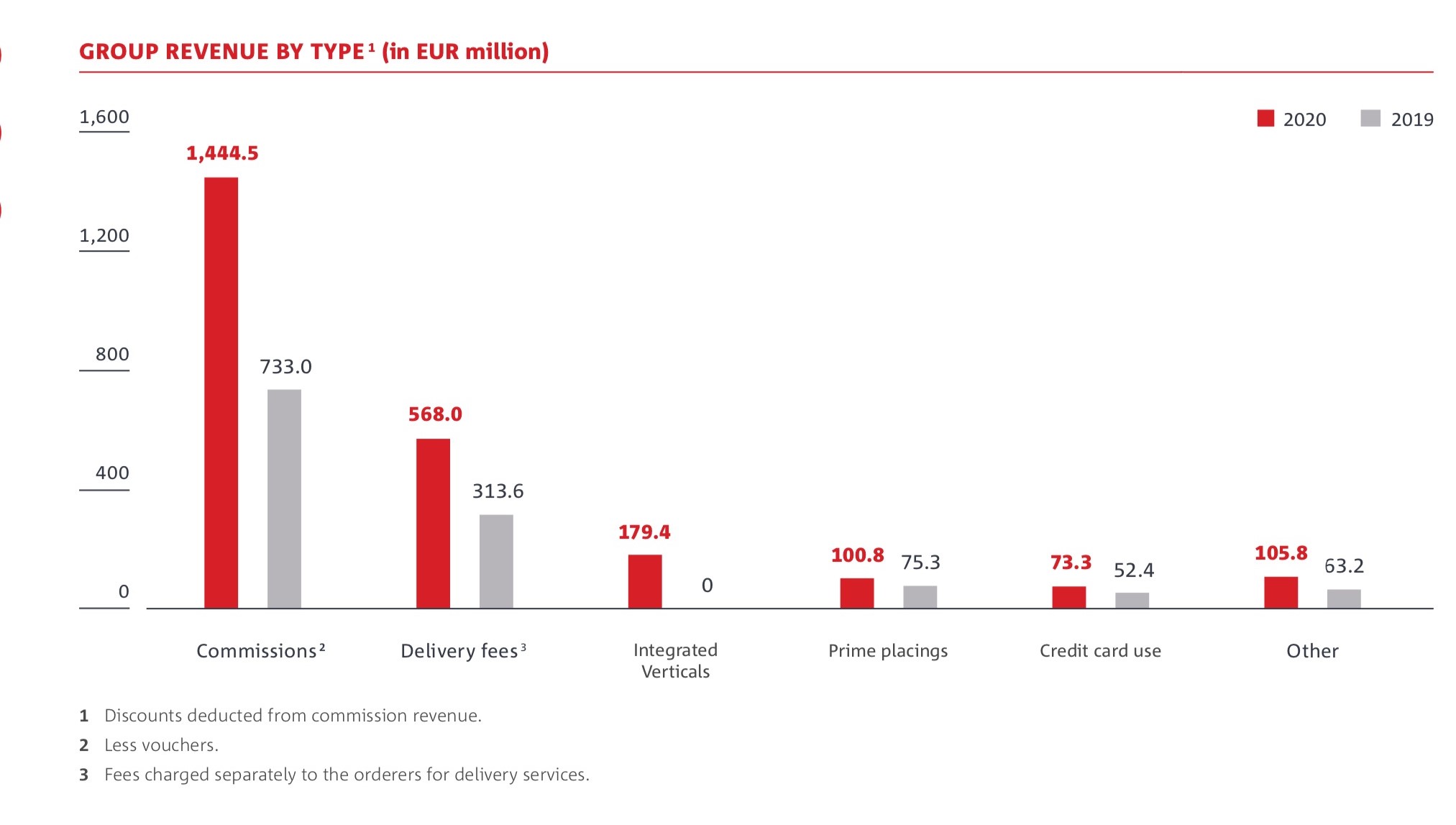

- Revenue, mostly commissions and delivery fees, increased +95% in 2020 to 2.5B euros.

However…

The company is still very negative in operating margin and cash flow. So what’s going on?

Delivery Hero Is Following the Standard Digital Playbook. Sort of.

The standard playbook for a software company (whether a platform or not) is often the following:

- Target a 10x or 100x market opportunity.

- Grow users and revenue.

- Capture and grow cash gross margin. Not the %. The cash.

- Flood cash into new revenue streams and innovation to improve the user experience.

That playbook is all about building a digital business on the demand side. It is about identifying a big opportunity and then systematically improving the consumer experience and going after related consumer problems.

However, this also usually results in negative operating profits until sufficient scale is reached. The gross profits are positive but the operating profits are negative. Often for a long time.

However, with increasing scale the operating leverage eventually kicks in and the big profits are revealed. And analysts routinely underestimate the size of the opportunity and how big the cash flow can be with a healthy gross margin. Analysts have routinely underestimated how big companies like Amazon and Alibaba were going to be.

And along the way, the company keeps doing #4 and growing new revenue streams and improving the user experience. It’s about going for massive demand-side scale.

When this works, it can be amazing. But when it doesn’t, business problems can be hidden for a long time. Because everyone accepts the negative economic profits as part of the strategy. Uber and WeWork both told this type of story for a long time. Investors eventually realized no profits were coming (thus far).

Take a look at Delivery Hero’s financials.

You can see the 20% gross profits. And you can see the strongly negative operating profits, mostly because of marketing spend. There is also significant spending on IT. You can ignore the big expenses in G&A in 2020. That is from M&A activity.

So you could say DH is in the earlier stages of the standard digital playbook – which is exactly when you would want to invest. If you believe in the company’s future.

However, what is different about Delivery Hero is it is going for scale by aggregating lots of smaller markets. And by M&A.

This is not a typical US or Chinese digital company that goes for scale in a core markets. Delivery Hero is almost entirely focused on smaller, peripheral markets around the world. That is really interesting.

- DH is going for demand-side scale internationally.

- DH is avoiding the major markets – and the large ecommerce companies.

- DH is centralizing IT costs across its markets.

This looks like local marketplaces, logistics and marketing PLUS global scale in IT, data, financial resources and innovation.

But you can see the standard digital playbook in the company’s statements. The annual report speaks directly to how it is using innovation and technology to improve both the consumer experience and restaurant partner value.

- For consumers, the focus is personalization, recommendations and increasing services.

- For restaurants, the focus is enhanced value from forecasting demand and supply, inventory management, faster and better delivery capabilities and marketing solutions.

So you could say this is the standard digital playbook with an international twist.

And that’s true.

But to me (the competition guy), this looks like a specialty ecommerce company avoiding the tech giants. And I like that strategy in general.

Take a look at my five questions for specialty ecommerce viability. Especially #5.

- Is the company sufficiently differentiated in the user experience?

- Yes against smaller marketplaces for food and physical retailers.

- But not against large tech companies doing on-demand delivery or restaurant marketplaces.

- Can the company compete and/or differentiate in logistics or infrastructure without ongoing spending?

- It doesn’t need to do big ongoing spending (i.e., building warehouses) but it is also not differentiated in infrastructure.

- Does the company have a strong competitive advantage in a circumscribed market?

- Restaurant reservation and delivery marketplaces have network effects. The market leader should have a superior service.

- Is there a clear path to significant cash flow? That the big question.

- Has the company avoided markets and situations that are attractive or strategic for the major ecommerce companies? In many markets, yes.

#5 is the twist.

Compare DH to Dingdong, which does on-demand grocery delivery in China. Dingdong must go head-to-head with China’s ecommerce giants – who view groceries and on-demand services as strategic priorities. In contrast, DH is doing food delivery in South Korea, Bahrain, Poland and other smaller and circumscribed markets. You’re not going to see big Amazon and Alibaba activities in these markets.

However…

Problem #1: You Have to Look at Competition Country-by-Country Going Forward

I like how DH is picking its markets and avoiding the ecommerce giants. That’s a good approach for specialty anything. But it may not work. Digital capabilities are really good at going international easily. For example, in Thailand, Delivery Hero has FoodPanda, which is pretty good. But Grab and GoJek are also doing food delivery and supermarkets. And Line and others have jumped into delivery.

The “avoid the giants” strategy works better when there are bigger barriers to entry. Like having lots of factories or retail shops. The more a company is just digital, the easier it is to enter new markets. So DH may not be about avoiding the giants. It may be mostly about getting to these markets early. Then it needs to capture and create strong habits with consumers. I would be looking at DH market share and its stability country-by-country.

I would also go country by country and look at current and potential competitors – especially:

- Similar marketplace platforms for restaurants and supermarkets.

- Super apps with bid consumer adoption.

- Other specialty ecommerce players.

- Large retail food chains.

- New entrants.

Keep in mind, DH will have a scale advantage in IT spending versus smaller, purely local competitors. But not in the other major costs of delivery and marketing. Those are local and variable costs.

Problem #2: Unit Economics Are Going to Vary Country-by-Country

Food delivery is generally not a cash machine. The labor costs can be significant against the size of the orders in many markets. And these are variable costs, so they don’t decrease with scale.

However, food marketplaces are a differentiated service where people do spend significant money on some orders. And they use these service frequently. I like digital marketplaces for restaurant reservations. And restaurant delivery is a natural complement to restaurant reservations.

We can see a 20% gross profit today. And hopefully, that can increase over time with greater geographic density and other moves. But is the company going to reach positive operating cash flow eventually?

You really have to go country by country. And two big issues jump out:

Labor costs and issues per country.

DH classifies its workers as independent contractors or gig workers. They are generally not employees. And lots of countries have a problem with that. The labor costs could change over time. And they could be very different country by country. Note: China is currently addressing how Meituan’s are compensated.

Plus, there will be ongoing labor issues. Something DH is already dealing with in several countries.

Local competition per country.

The competitive intensity now and in the future is going to be a big determinant of unit economics. New companies could enter. Big retailers could offer competing products. And the competitive intensity could increase.

DH runs marketplaces based on network effects. That is great but it means they are dependent on keeping users coming to the platform. This could force them to continually spend on sales and marketing to keep usage up. Note the below sentence buried in their Risk section. The word “high” got my attention.

Final Question: Can Foodpanda / Delivery Hero Get to Profitable Scale in On-Demand Food?

The standard digital play book is all about getting the demand side to scale when the big cash flows theoretically kick in. Whether this will work depends on lots of things.

Here are my questions for Delivery Hero:

- What revenue is required for operating break-even in food delivery in each market?

- Growth and revenue will depend on the macro situation and local competition.

- Growth and revenue will depend on local network effects.

- Gross profit is 20%. How will this change over time in each market?

- Will this increase with geographic density?

- What are the near-term revenue streams to complement food delivery?

That last point could be really compelling. If they can successfully add increasing revenue streams, the economics could change significantly. And this is clearly what they are trying to do.

Overall, I putting this as a 5th business model for on-demand food:

- Grab and Uber do:

- Mobility as a commodity service.

- Food delivery as a differentiated services marketplace. Expanding to groceries.

- Payment (not Uber).

- Meituan and GoJek Indonesia do:

- Food delivery as a differentiated services marketplace.

- Lots of other local services.

- Cross-selling plus geographic density.

- Alibaba and ele.me do:

- Ultimate B2C marketplace for products and services,

- Dingdong does:

- Grocery retail (not a marketplace) with an asset-lite on-demand delivery model.

- Delivery Hero does:

- Food: Restaurants, groceries, cloud kitchens, quick commerce.

- On-demand delivery.

- International expansion to get there first and avoid the ecommerce giants.

That’s my take. I hope that is helpful.

Cheers,

jeff

———

Related articles:

- Dingdong vs. Oriental Trading: How to Spot the Specialty Ecommerce Winners (1 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Dingdong and 5 Questions for Assessing Specialty Ecommerce Companies (2 of 2) (Asia Tech Strategy – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Can Dingdong Win in Groceries and Specialty Ecommerce? (Asia Tech Strategy – Podcast 90)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Specialty ecommerce

- Standard digital playbook

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Delivery Hero / Foodpanda

Photo by Rowan Freeman on Unsplash

Graphic by GenAI

———

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to accelerate growth with improving customer experiences (CX) and digital moats.

I am a partner at TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase growth with improved customer experiences (CX), personalization and other types of customer value. Get in touch here.

I am also author of the Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.