This week’s podcast is about scale advantages. Which are different than economies of scale.

You can listen to this podcast here, which has the slides and graphics mentioned. Also available at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is the link to the TechMoat Consulting.

Here is the link to our Tech Tours.

5 Things People Get Wrong about Scale Advantages, Economies of Scale and Moats

- There are lots of absolute (not relative) scale advantage. Growth is the default business strategy.

- Scale advantages are bigger (and more vague) than economies of scale

- Scale advantages can cascade

- Scale disadvantages (diseconomies of scale, big company disease) are under-rated and under-measured

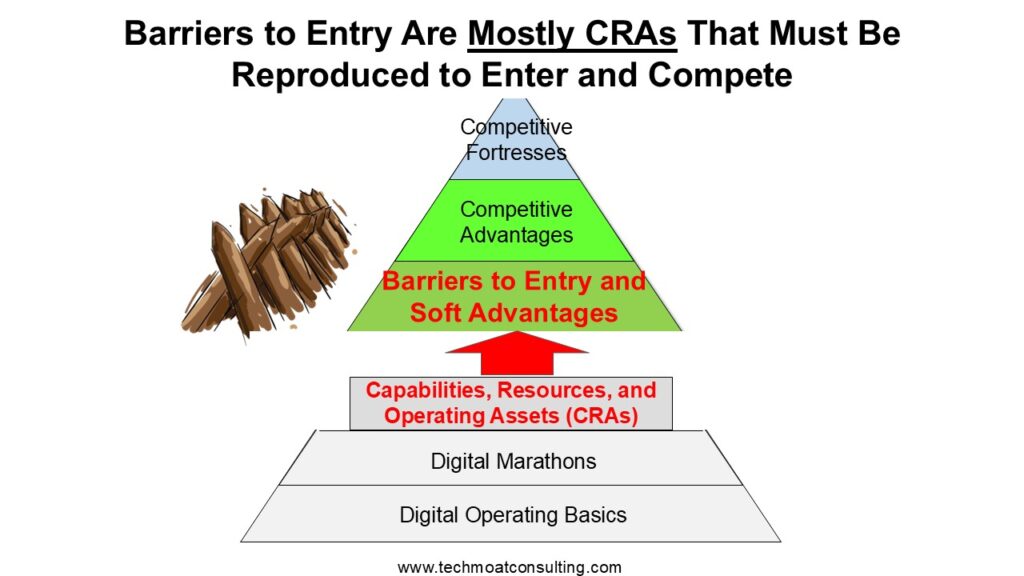

- You need to separate barriers from competitive advantages. And measure each specifically.

I want to know 3 things:

- Barriers to entry against new entrants.

- What specific CRAS to reproduce?

- What is the cost, difficulty and timing to enter?

- Competitive advantage against rivals

- Which CAs specifically? With measurements.

- The incumbent or rival response

Barriers List from Michael Porter (my interpretation, not exhaustive).

- Economies of scale. Need to get big to enter. Indivisibility of production capacity and purchasing power matters. Being a multi-business can help incumbent and entrant. Both can share the costs. Both can share the brand. Both can be vertically integrated.

- Brand loyalty. Must spend to overcome loyalty and habit. Also must overcome trust question.

- Capital requirements. Especially if the move is risky and costs are not recoverable (marketing and R&D spent is gone).

- Switching costs.

- Access to distribution channels. You need to convince retailers. This is not on my list.

- Cost advantages not related to scale. Similar to my CA list.

- Proprietary product technology / know how / patents / secrecy are hard to replicate.

- Favorable access to raw materials.

- Favorable locations (at low cost)

- Government subsidies

- Learning or experience curves

- Government policy. Licenses. Compliance costs.

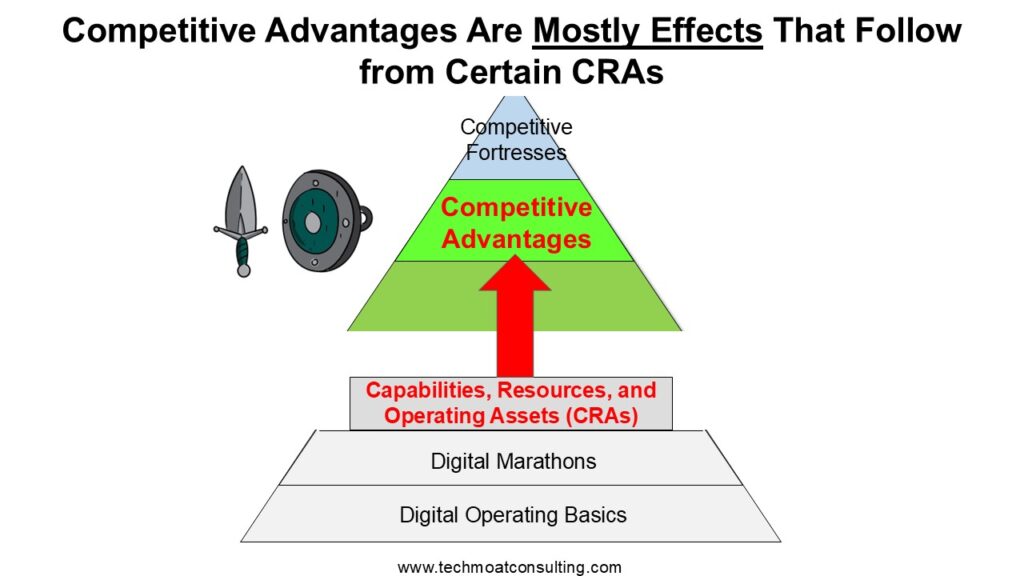

My interpretation of Michael Mauboussin’s list competitive advantages (not exhaustive):

- Customer Switching Costs: When customers face significant costs (financial, time, or effort) to switch to a competitor, companies can retain market share and maintain pricing power. Examples include software platforms with entrenched user data or services requiring retraining.

- Network Effects: A product or service becomes more valuable as more people use it, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that deters competitors. Social media platforms or payment networks like Visa are classic examples.

- Economies of Scale: Companies with large-scale operations can spread fixed costs over greater output, reducing per-unit costs and enabling lower prices or higher margins. This is common in industries like manufacturing or retail (e.g., Walmart).

- Intangible Assets: These include patents, trademarks, brand reputation, or proprietary technology that competitors cannot easily replicate. Strong brands like Coca-Cola or patented drugs in pharmaceuticals illustrate this advantage.

- Cost Advantages: Firms that can produce goods or services at a lower cost due to unique processes, access to cheaper inputs, or proprietary methods gain an edge. This could stem from process innovations or exclusive resource access.

- Efficient Scale: In markets where a limited size supports only a few players profitably, established firms deter new entrants. This often applies to niche markets or regulated industries like utilities or airports.

——–

Related articles:

- The Characteristics of Unattractive Industries with Cutthroat Competition (1 of 3) (Tech Strategy)

- 5 Misconceptions About Barriers to Entry (Tech Strategy)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Scale Advantages

- Scale Disadvantages / Diseconomies of Scale / Big Company Disease

- Competitive Advantage: Economies of Scale

- Scale Advantage Cascade

- Capabilities, Resources and Assets (CRAs)

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

———–transcription below

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast from Techmoat Consulting. And the topic for today, five things’ people get wrong about scale advantages, economies of scale, and really moats. Those three ideas tend to get all blurry and mixed together, but they’re actually kind of three different things and also to lay out in pretty good detail, at least how I think about them and how other people think about them. Charlie Munger and such. So anyways, that’ll be the topic today. So, a bit of theory, but not too long, I think. Okay, so let’s see. disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or my writing website is investment advice. The numbers and information for any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment legal or tax advice. Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the topic. Okay, so this is a bit of theory. So, there’s some ideas for the concept library here today. Really quite a few, but I’ll just focus on a couple main ones. Obviously scale advantages is a big topic, but one point is, which I’ll get into sort of five things I think people get wrong. Economies and scale and scale advantages, not the same thing. Economies of scale is much broader. It’s of, it’s messier. It’s the idea that a bigger company is just better in lots of dimensions than a smaller one. So, talk about scale advantages and the flip side to that is diseconomies of scale. Something Jack Ma calls big company disease. You know, when you get bigger across the board, certain things start working poorly and you start to get disadvantages. Next one would be scale advantage cascade. which is a Charlie Munger idea. It’s basically when you’re talking about scale advantage, this big fuzzy concept of, we’re a big company, not a small one. We get certain advantages. Well, some of those advantages cascade into other ones quite naturally. I’ll give you his sort of list for that. And then we get to something we’ve talked about before, economies of scale, which is a much more precise competitive advantage you can talk about. You can measure it very exactly, unit cost, things like that. I’ll just touch on two others which would be a competitive advantage flywheel which is something kind of interesting and then what I call CRAs which is really just stands for capabilities resources and assets. It’s this idea that like there’s a whole strategy sub-genre based on resources that the way you look at a company is a resource based of you. that this company has a ton of fixed assets, land, buildings, and that’s one way look at the company. But you can also look at it, not just assets, but you can look at resources. You have a lot of intellectual property. You can look at capabilities. You have a tremendous number of engineers who are good at making things smaller. Well, that’s Sony and people would argue that at least for a while Sony was really all about its capabilities and miniaturization. You know, they made the Walkman small, they made everything small. So, you can kind of look at strategy through capabilities, resources and assets as a resource-based view. I think that’s very helpful and I’ll, I didn’t really write about this in my book. I’m rewriting my Motes and Marathons books I think this year. I’m going to talk a lot more about that, because I didn’t really talk about that, and it is kind of central to a whole lot of stuff. So anyways, kind of a lot of ideas there. I’ll go through them, I’ll put it in the notes, and then it’ll be in the concept library. if it doesn’t make sense on the first pass, there’s more there. And I’m going to write this up for subscribers, I think, in the next day. So, it’ll come in another form. So, you get two passes of it if it’s helpful to you. Okay, so those are kind of the concepts for today. I know it’s kind of a list. So, let’s just get into five things I think people get wrong. Okay, number one, you can have absolute, i.e. not relative, advantages. You know, for years I’ve been saying, okay, economies of scale, this is a relative advantage in the sense that you got to be bigger than your other party, your rival, and how much bigger than you are matters. And if that scale differential decreases, you lose your advantage. And also, that economies of scale as a competitive advantage Usually only one player can have that. Not always, like you can have two or three giants that don’t have scale advantages between each other, but they have advantages versus all the other smaller players. Coke and Pepsi have, you know, sort of relative scale advantages versus all the small sodas of the world, but not versus each other. Okay, so I’ve always talked about economies of scale and things like that in relative terms. Well, you can also talk about absolute. scale advantages not economies of scale advantages and really, that’s kind of the go-to default business strategy for everybody which is get bigger We’ve got to grow because everybody knows if you grow life gets easier Lots of good things start to happen. You get lots of good advantages and you know, it’s not relative. There’s a world of difference between being a small company with 5 to 10 to 15 people and one with 100. Well, let’s say 2 300. And it really doesn’t matter what competitors do. That sort of let’s get big absolute scale advantage. Anyone can do it. So why is that mostly true? Well, obviously you have more resources. That’s the big one. You can’t do that many initiatives if you’re a smaller firm. You don’t have that much cash, usually. Not always, usually. You don’t have that much sort of bandwidth to do new initiatives and new projects. You’ve got to really focus down on what you’re doing. Generally speaking, management is less capable. highly trained managers, they like to say they’re like sports stars and the best players go to the best teams. They’re not that good, give me a break. But yes, it’s generally true that larger firms would money get people with sort of more depth of expertise, things like that. When you’re smaller, well, now the flip side to that is if you’re smaller, People tend to be more driven. You know, you’re flying a lot closer to the tarmac So, you know people are really intent you ever meet like owner managers who run small businesses Man, they are all over that business seven days a week. You know that little business is Their future it’s their kid’s college education. It’s everything so in many ways there’s you know that management comment There’s some subtleties there You have less diversification. Obviously, you’re more dependent on one to two products. Generally, your revenue is smaller. Those two factors together means you’re more exposed to changes in the environment. You know, you’re flying a plane and you get hit with a storm, but you’re up at 20,000 feet, it’s not so bad. You get hit by a storm flying at 100 feet above the ground, yeah, it’s a problem. Your one core product loses a lot of revenue, it’s a problem. You’re laying off people immediately. So, less diversification, less rain. You’re basically more exposed to the elements and to changes. So generally speaking, being bigger is an absolute advantage. You get scale advantages sort of across the board. It’s the default business strategy, let’s grow. Now I did a podcast last week about fragmented industries and that’s an exception to that rule. That’s where you got to kind of be careful where you realize actually getting bigger would be a mistake. One, it’s not going to work. Certain industries can’t grow. And two, even if we do grow, it’s probably going to hurt us in terms of the quality of service we provide. So, and you can listen to that podcast if you want, but yeah, there’s some exceptions. Now that doesn’t mean don’t try at all, but you know, if you have one restaurant, you know, go for five. That’s great. But if your whole plan is we’re going to be a couple hundred, it’s probably not going to happen. So anyways, fragmented industry is a bit of an exception. There’s a good book called Small Giants. which is about how do you become really strong and powerful and profitable as a smaller company where growth is really not the strategy anymore. Another bucket to think about, when I went to business school I had a professor named Bruce Greenwald who wrote, he’s a pretty well-known guy in terms of competitive advantage. He wrote a book called Competition Demystified which is quite well known. And he has a standard slide where he would always say like, the number you look at is what is your return on invested capital versus your cost of capital, your WAC. And growth can be good, bad, or neutral depending on that. Now if you have a franchise where you have a return on invested capital of let’s say 18%, your cost of capital is 9%. Growth is going to help you. It’s going to increase the economic value of the company because you’re going to put in money at 8 or 9 percent and it’s going to turn into money at 16 percent. So, you made money. In that case growth is a good idea, assuming it’s done smartly. And the flip side is you can look at when the ROIC is below the cost of capital. So, every dollar you put in, you’re basically decreasing the value of a dollar. Now that kind of thinking is usually not done at the business level. It’s usually done at the product level, sort of NPV thinking. But yeah, I mean, you want to kind of think about that. Like a lot of times the growth is a mistake and you’re going to destroy value. So those scenarios do exist. You can do the same sort of thinking when you compare sort of enterprise value to asset value. you know, we have so many assets, let’s say $100 million of assets, but they’re only when you actually generate products and revenue, the earnings power value is like $80 million. Well, in that case, you should, one, fire the management. Actually, that’s not me saying that. That’s standard management textbook thing. Like, if you see a factory that costs $100 million generating cash flow that’s worth $80 million, you need to replace the management or sell the factory. a good business. You know the Soviet Union was literally full of businesses that did exactly that. So anyways just think about that that bucket is kind of interesting. Okay so that’s really number one. Think about absolute scale advantages. It’s pretty cool, pretty interesting. All right point number two things I think people get wrong. Scale advantages as an idea, as an advantage, is bigger than economies of scale. Now economies of scale, we’re usually talking about something like lower unit costs because I have a factory that’s producing 10,000 units, you have a factory that’s producing 5,000 units, we have the same factory, so my per unit cost is less. Fine. And then… You can also flip that over to the more strategic costs, which is I have fixed costs I’m spending on marketing. I’m Coca-Cola. spend five, I don’t know how much they spend on marketing. I think it’s 5 % of revenue. You know, on marketing, you’re Dr. Pepper, you’re much smaller. Your 5 % is smaller than mine. I’m flooding the local town with marketing. So, I get economies of scale in marketing. And you can do this with fixed cost, can do it with sort of maintenance, capex, which you got to keep in mind, things like that. Fine. But when we talk about scale advantages, that’s much broader than that. you know, basically you need to sort of think about the relationship between you and other parties. So, everything I’ve been kind of saying, I’ve been using these analogies of like it’s Coke versus Pepsi or it’s Coke versus a smaller soda. Those are competitors. or let’s say new entrants, you also have to think about your relationship with buyers and you have to think about your relationship with sellers and you need to think about your scale advantage or disadvantage in all one, two, three, four of those interactions. And usually, we only talk about rivals and new entrants. You got to think about buyers and sellers. It can make a big, big difference. Now, we often talk about purchasing costs as an advantage, is if you’re a big, buyer, bigger than your rival, you can acquire your cost of goods from your supplier cheaper than they can. And therefore, you have a cost advantage. And that is true in many cases, but not always. Not always. If one of your costs of goods sold is sugar and you’re Starbucks. Can you really go out into the open market for sugar, the global market, and demand any sort of discount really? It’s kind of a big open market for everyone. you know that sort of scale advantage is not going to matter against the sort of global market like that with set prices. The one I talked about the other day is if you’re a driver on Uber, you might… Let’s say you have a team of 10 drivers versus someone who’s got one driver. You’re not going to negotiate better terms with Uber. You’re not going to say pay me more. No. We don’t use the word scale when we talk about buyer power and supplier power. We usually talk about bargaining power. It’s the same thing. You know, you have no bargaining power as an Uber driver over Uber. It doesn’t matter how big you are. So that’s a scale question as well. And you can also do it on the supply side. We do see scale advantages on the supply side from time to time. But in other cases, it doesn’t work at all. anyways, scale advantages, you really need to take it apart by all of those four main interactions in sort of Porter’s Five Forces. buyer power, supplier power, rivals, which we call competitive advantage, and then new entrants, which we call barriers to entry. You want to look at all of them. I mostly focus on those last two, barriers to entry and rivals. Okay, now what kind of advantages do you get across the board in a big fuzzy way with scale? You’ll see this list a lot of places. I actually saw a JPEG on Twitter the other day by a guy named Brian Feroldi. So, I’m going to read that list. I don’t want to take credit for it. It’s not my list. But it’s pretty standard to what you hear. It’s like number one, you can get lower unit costs. Talked about that. You can get increased bargaining power. Walmart absolutely has purchasing economies of scale versus everybody who wants their stuff at Walmart. Totally true. Other ones he mentions are access to financing. You can get lower rates. That’s definitely true. Smaller companies, much harder to get good credit rates than large companies. You could argue that’s a cost. You could say that’s a bargaining power, purchasing power type cost. You get more technological innovation. You get more tech investment. Okay, scale and R &D. You also get sort of more specialization. It’s very different to say we’re spending all of this money on one specific thing. mean, the iPhone, Apple spends an enormous amount of R &D money every year just on smartphones. You know, if you have specialized R&D and you’re bigger than your competitor and you’re doing it all in one area, a company I like is called WABCO, which I heard about years ago because Buffett invested. All they do is braking pads and braking systems for trucks. And they spend a lot of money on that one single topic. And they’ve been doing it since like 1905 or something, where they used to do brakes for carriages on being pulled by horses. And then they did, you know, Model T cars. Like you can see how an advantage would be. You can get better and more specialized staff. quality of staff matters, greater specialization matters, you’re going to be more effective, you’re going to be more efficient, probably cheaper. Brand awareness and brand spend, marketing spend. Yeah, talked about that one. Diversification, I kind of talked about that one. Reach and resources. Yeah, if you’re trying to get distribution for your product, helps a lot if you’re bigger. You can access more resources, various things. And then the other one he mentions was patents. So, I think he also put globalization in there. Anyway, you can see it’s kind of a big list. Like it’s not just what I’ve been talking about economies of scale. No, it’s a big list when you get bigger. Now I don’t usually use that list too much because I find it too fuzzy. I prefer to take it apart like competitive advantage versus rivals, barrier to entry versus new entrants, bargaining power versus suppliers, bargaining power versus customers, which comes up in demand side discussions. I like to do it very… specific at those levels, but I do recognize that I’m missing some factors by doing that, some of these fuzzier factors like management quality. That’s not really in my models under economies of scale. I have it in another section of just management ability. Okay, so that’s number two. Scale advantages are much bigger as a thing than just economies of scale, even though people use these two terms sort of interchangeably. All right, number three. scale advantages can cascade. This is one of the concepts on my concept library. This is a Charlie Munger term. The scale advantage cascade. I think that’s it. I use the word cascade, but scale advantage cascade, which you know, he’s basically talked, he writes about this stuff over the years. He basically said, look, all those advantages I just mentioned for scale. Certain scale advantages naturally lead to other ones. They do sort of cascade once. Once you get one, you can start to get a second, a third, a fourth. It’s a cascade effect. So, for example, I think the one he talked about is you’re a big CPG brand and you have a lot of scale in your production and distribution. Okay, you can get your products out there, you’re making lots of whatever you want to call it, soap. You’re distributing it to all the stores. That is a scale advantage for sure. Well, you’re also getting more volume sold, so that leads to a scale advantage in terms of your marketing spend. You can outspend everybody on marketing. Increasing marketing spend leads to a greater sort of awareness advantage. that customers are more aware of your brand. That’s an information advantage. There’s also a psychological effect that you’re more comfortable with it, you trust it, it becomes a habit. But big marketing spend, which is one type of advantage, naturally leads into what we would call an awareness advantage, or an information advantage. That matters when people come in. You can get another advantage you call social proof advantage. When you see everybody buying that brand of soap, we absolutely copy what other people do. We assess quality by what other people do. We desire what other people desire. So, there’s a social proof advantage. You can see those things kind of cascade one two three four Over time you can also get a specialization advantage. You can get a purchasing advantage for advertising but yeah, you can kind of map those out over time and how you get them I think that’s the right way to think about it So anyways, that’s kind of a fun concept to think about scale advantage cascade I used to call these competitive advantage flywheels That when I’m bigger than you is Coco. Let’s say a beer brand I don’t know, Antarctica beer in Brazil. You know, this is the 3G guys. That was one of their first moves. I think it was literally their first move into the beer business was buying Antarctica and Brazil and then taking on the leader. And you know, they were very focused on we’re going to be big. We’re going to push all the points of distribution very aggressively. And we’re going to be so dirt cheap that we can flood more money into marketing spend. So, distribution advantage led to marketing spend advantage. And then the marketing spend advantage led to greater habit formation, greater awareness advantage. And you can actually look at their market share year after year, and you can see the numbers move. Actually, we can see this in beer going back really to 1980. If you go to the US and you look at the main beer brands, there used to be about nine or 10 of them, major companies in 1980. And year after year, that little process happens and the market share shifts more and more to a couple larger players. And you fast forward 20 years and it’s three to four players. You can literally watch this cascade, or I call it a flywheel, play out in market share. as these advantages sort of grind the competitors down slowly over time. Scale advantages. Anyways, it’s also why, you know, Jack Welch, when he was at GE, he used to say, we only invest in the first and second place companies in a sector or we don’t do it. I think that had to do with basically all these scale advantages. You don’t want to be four or five. You want to be one or two. Anyways, that’s number three. All right, number four, this one’s short. Dys economies of scale are underrated and definitely under measured. So, the idea you get bigger, you get this sort of various types of scale advantage, but you also get some disadvantages, diseconomies of scale. What Jack Ma calls big company disease. And it’s absolutely true. It’s not a small thing. You know, people really don’t talk about it as much and they definitely don’t measure it. So standard ones, you get a lot more bureaucracy. Suddenly you’re managing lots of different business units. You got people in multiple countries. Bureaucracy is really the problem. People do act in their self-interest. not necessarily in the interest of the company. Business units often act in their self-interest as well. They don’t want their people taken, they don’t want the other business does well, they don’t like that, they don’t share resources. So, you get a lot of internal self-interest that plays out. Bureaucracy is a major problem. I actually just think it’s the nature of human beings. You can’t put too many of us together in a project or a building. without bureaucracy and politics sort of rearing its head. And the only cure I know of is competition. Well, two cures. One, customers. If they don’t like your product, they’re not buying. Great. And competition. Like those two forces seem to be the only thing strong enough to stop this, which is why government bureaucracy is such a problem. because there’s not really any direct feedback mechanism from customers and there’s no competition. It’s monopoly. So yeah, see bureaucracies as sort of, know, every now and then you’ll see a bureaucracy get stripped out of an organization. It’s usually because of a competitor or some maniac at the top, kind of like an Elon Musk character, just tears it apart over 10 years. I mean, Twitter had major internal management and bureaucracy problems. Okay, well, if you fire 80 % of the staff or show them the door gently, that is one solution. Anyway, so that’s a big one. The one VCs talk a lot about is being slower. Small companies are just much faster. VCs talk about this a lot, like the only advantage that small companies have is they’re fast. You got to move fast. It’s your one big advantage and you don’t have any legacy costs or legacy structures that you have to protect. You can jump from idea to idea without having to fire hundreds of people. That’s pretty good. Other disadvantages, you’re exposed to specialized plays. New businesses jumping in, they’re more specialized. You know, it used to be you got the big newspaper. I can remember. The Sunday morning newspaper. you this must be 1980, 1985, that the big newspaper that would come on Sunday morning was the Contra Costa Times in my area, Northern California. And it was massive. I mean, it was two, two and a half inches thick. And it was just this huge, massive thing. And it had the arts and leisure section and it had the sports section. It was great. You could, and you would take all the parts apart and everyone would take a section. It was great. Well, yeah. That makes you very vulnerable to a cool new magazine that comes along and says, only do arts and leisure. That’s all we do. Okay. When you get big, you get vulnerable to specialization. mean the way Munger lays it out, which I thought was interesting, he says bureaucracy comes first. I’m paraphrasing obviously. That leads to misaligned incentives and that leads to corruption and information problems. That last one is pretty interesting actually. That as you get bigger, you see all these internal information problems. Actually, you know what you can do is you can think about it like marketplace platforms. I talk about a lot because they’re all about lowering the coordination and transaction costs. So suddenly you can do a business deal with someone who’s not in your city. because there’s lots of transaction costs. There’s information, there’s finding the other person, there’s getting it done, but online platforms like Lazada let you do that. They lower those costs and you can do the deal easily. You can make the same argument that that happens within companies as well. As they get bigger, the internal coordination costs go up. and it’s very hard to get things done. There’s a lot more finding the person, coordinating. There’s a lot of information asymmetries. Not everyone knows or thinks what you think. Your incentives are not aligned. So, you can kind of make the, and a lot of companies talk about that, that we are building sort of these coordination platforms outside and inside the company. It’s pretty fun to think about. Okay, last one. Anyway, so that’s diseconomies of scale. They’re underrated and people don’t measure them enough. Number five, last one. You need to separate this down to barriers to entry and competitive advantages. Okay, so I talked about economies of scale, diseconomies of scale. Now we’re going to bring it down to sort of just to how you deal with rivals and how you deal with new entrants. So, this is. 80 % of what I’ve been talking about when I talk about economies of scale. I’ve been talking about this. But this doesn’t apply just to economies of scale. This applies to all the sort of competitive advantages at this level of these two forces. So, there’s a couple lists I’ve been looking at. Michael Porter, I’ll put this in the show notes. If you read his competitive advantage book, he has a list of barriers to entry. And I’ll read them to you. I’ll put them in the notes as well. Economies of scale that enter a firm. So, we’re talking about new entrants breaking into a business. You need to get big enough to enter. You need to have production capacity that’s significant. You might need to have purchasing power. That’s a thing you have to overcome to get in. Brand loyalty. You must spend some money to overcome the fact that people don’t know you, there’s no existing loyalty or habit, they probably don’t trust you. That’s a barrier. You’ve got capital requirements, spending on marketing, spending on R &D, maybe spending on tech. That’s a barrier, you got to spend that. Heedless switching costs. that if the existing customers in the market already have, let’s say, long-term contracts with the existing player, you’re going to have to break into those somehow makes it harder. Access to distribution channels. You’re a new soda. You’ve got to convince all the retailers to stock your good. That’s a barrier to getting in. Cost advantages that aren’t related to scale. that’s technology let’s say we could call it patents, IT, I don’t know, buying land, things like that. Number seven, proprietary technology, patents, know-how, secrets. It doesn’t have to be a filed patent, it’s just know-how and sort of industrial knowledge. You got to replicate all that. Favorable access to raw materials, favorable locations at the right cost. You can’t open a really nice hotel out in the middle of nowhere. It’s got to be downtown. Government subsidies, learning and experience. So, you can see when you read this, a lot of those don’t sound like barriers to entry to me. A lot of those sound-like competitive advantages. Okay, you’re a big soda, Coca-Cola, I’m a smaller soda, but we’re both in the business. You still have an economies of scale advantage over me. It’s not a barrier to entry. That’s competitive advantage against a rival. I’m already in. Switching costs. You know, if we’re both selling ERP systems and you sell the big client, well, you’re locked in with major switching costs. That’s a real problem for me. So, a lot of these to me, there are a mix of sort of barriers to entry and competitive advantages. There’s things that would stop a new entrant, but there’s also things that would give you an advantage over a rival. So, I think these two ideas, and I hear this all the time and I kind of gripe about this online sometimes, people, they kind of mix all these things together. And just know that they’re really not the same thing. Even though some of the effects are similar, they’re actually quite different. So, another person who writes about this is Michael Mauboussin, who wrote that book. What Measures Moats? I forget. I’ll put the link in there. Very famous paper. I mentioned it last week. And he kind of says there’s six competitive advantages, not barriers to entry, competitive advantages. And he basically, I don’t think his stuff on competitive advantages is very good. I think his other stuff on ROIC and industry structure is great. I think the customer advantage, competitive advantage stuff is not too… There’s not a lot of depth to it. But he will list things like customer switching costs. Okay, we heard about that. Network effects. Is network effect a competitive advantage or is it a barrier to entry? He says it’s a competitive advantage. Economies of scale. Well, Porter just said that was a barrier to entry. Is it both? Intangible assets, patents, trademarks, brand reputation. Cost advantages, he has something called efficient scale, which I’ve written about before, I won’t go into that, it’s kind of interesting. And then he goes into sort of like supply side competitive advantages. Complexity, if something is very complex to produce, that creates an advantage. Toyota, Hamilton Helmer talks about this as a process cost advantage. Patents can be there learning advantages, which I’ve written a lot about resource uniqueness things like that distribution so You know when I go through these It looks to me kind of very confused. So, I have a very sort of simple clean framework that I use I should think it’s better but You know, I’ve been thinking about this one particular question, competitive advantages in digital businesses for like eight years. So, this is kind of my one question. So, I should be a little better at it in my opinion. Okay, I just want to know three things. All those lists, blah, blah, confusing. I want to know three things. What is the barrier to entry against new entrants? describe it to me specifically such that a well-resourced and well-run company would have to overcome this to get into the business. I want a good, solid competitor who’s got some resources and expertise, and this is the barrier that’s going to stop them. I want to know how tall it is. the wall. I want to know how much it costs to overcome it. I want to know how long it will take and I want to know how difficult it is. Those are my three metrics for barriers to entry. How much does it cost? How long will it take? And how difficult is it to overcome the barrier if it’s a fairly serious person looking to jump in? That’s question number one. Number two, what is the competitive advantage against current rivals? It could be a rival who’s bigger than me. I could be Dr. Pepper, small, they could be Coke. We could be the same size or could be I have a scale advantage over them. You can build advantages even if you’re the smaller player. You can build in switching costs. You don’t have to be the scale leader. A lot of these competitive advantages are available to everybody. Okay, I want to put numbers on that. And I have very specific numbers I look for. I basically map out exactly what competitive advantages I think it is. It’s very specific. And then I measure them. Okay, what is your scale differential? What is your pricing premium that you can charge over the other? And generally speaking, if the outcome measures for barriers to entry are cost, difficulty, and timing, The outcome measures for the competitive advantage against rivals is change in market share and pricing. Do you have a stable market share versus your competitor or is it going up and down every year? Because if it’s going up and down, you don’t have a barrier. You don’t have a protection against them. If your pricing is going up and down where you can’t command a return on invested capital, that’s okay. You don’t have a competitive advantage. Anyways, I’ve got whole list of how to break those down, but those are the things I’m looking for. And the third one, the last one, which I don’t talk about that much. Okay, tell me what the barriers are and give me the measurements. what the competitive advantage against rivals is and give me the measurements. Number three, what is the leader or incumbent response? If you’re going to break into an industry, it’s not just is there a barrier, but what is the incumbent going to do when they see me coming? That’s a big deal. Some incumbents are really scary. Others are not a big deal. One of the reasons I think Elon Musk did so well in SpaceX is because the incumbent was basically a government program, NASA. There wasn’t really anyone there that was scary that you wouldn’t want to jump in. You want to jump into a business and go head-to-head with Amazon in their core business? No, absolutely not. They’ll crush you. What if it’s a peripheral opportunity that they don’t care about? Okay, that would make sense. So, you got to think about either the incumbent response or the incumbent or the rival response to your action. Those are my three things. I’ll put those in the show notes. Okay, so how do I tell those apart? Like I give you, you know, in books and all that. I give you two very specific lists. One for barriers to entry, one for competitive advantage. And I don’t consider them the same thing, even though they can look similar. So, I don’t sort of mix these lists together. And basically, here’s the way I see it. Barriers to entry mostly follow from CRAs. They follow from capabilities, resources, and assets that you must reproduce to enter. Not from all the CRAs. I mean, if you build a business, there’s tons of assets, there’s tons of resources, there’s a legal department and an account. No, not all of them. But the key ones that matter, which is usually a short list, how difficult, expensive, and long term does it take to reproduce the key CRAs such that I can enter and be a viable player. I may be smaller than the incumbents, but I’m in. That’s the wall. And for those of you who do valuation stock picking, this is reproduction value. You look at the balance sheet, you can create a reproduction value for some of the physical, tangible assets, piece of land, a building. But you also have to think about the intangible assets. Legacy brand. Coca-Cola has a very powerful legacy brand that is very difficult to replicate. And one of the reasons I put in there how difficult it is to reproduce these assets, to jump the buried entry. Some of them it’s just about money. Build the factory. That’s cost. Others it’s about timing. You cannot reproduce the Coca-Cola legacy brand in one year by writing a check. You’re going to have to spend five years at least if it’s even doable. Some things take time. But and there’s other things it doesn’t even matter how much time and money you invest. You want to make hit songs? May not work. You want to invent a new drug? spend all that money, spend all that time, it’s difficult. So, timing costs difficulty. But generally, I’m looking at reproduction value. I’m looking at a list of assets that have to be replicated to jump into this business and be viable. So, barriers to entry to me are mostly a reflection of specific assets. competitive advantages are different. I’m not going to beat the other cola company. because I have a little bigger asset or something. Competitive advantages are effects. They’re sort of effects that follow from certain CRAs, but they aren’t the CRAs themselves. When you take a resource-based sort of look at an industry, competitive advantages are sort of the other side of the coin of resources. They’re just these funny effects like network effects. that just sort of appear when you have an asset base in place. When you build a network, that’s the asset. But the network effect that manifests itself, it’s kind of an effect that shows up from the asset, but it’s not the asset itself. And so, I usually look at competitive advantages as effects that… follow from a much smaller list of CRAs. Like you have a lot of CRAs, capabilities, resources, assets in a company. A small number of them are basically barriers to entry. A smaller number of them can sort of manifest as competitive advantages. Competitive advantages are much rarer. But they’re much more powerful, I think. So anyways, that’s kind how I break it apart. And I’ll put my sort of graphic in the show notes for how I map that out in my little six levels of competition. yeah, so that’s why when I’m rewriting these books, I’m talking a lot more about capabilities and assets than I did in the current version. Because it really, you have to think about operating assets, operating activities, and then you think about how those can lead to structural advantages, which can be barriers to entry or they can be competitive advantages. But that asset, the CRA piece is actually quite important. Anyways, that is the last point, which is you really got to separate these two things out. And it turns out things like economies of scale, it’s not really an asset that you have to, there’s a barrier entry aspect of economies of scale. You have to replicate a certain amount of production and distribution capacity. That’s the asset you have to reproduce to jump in. But economies of scale, once you’re in the business, it’s very different. You’re looking at throughput and efficiency of production versus arrivals and how that changes over time. Well, that’s kind of a different thing. And you would measure that differently. So, when you glom that together, like barriers to entries, nah, you got to separate it out. It’s two different questions. So anyways, I think that’s enough for today. So much for being short. That never really happens. I always say that this one’s going to be short. I don’t think it’s ever actually happened. I always seem to go to the same length. But anyways, those are kind of the five things. I’ll put them in the show notes. Number one, are no absolute, I’m sorry, there are absolute not relative scale advantages. Scale and growth is the default business strategy for a reason. A lot of advantages to be had. Scale number two scale advantages are bigger than economies of scale. It’s a much bigger but also kind of messier topic Harder measure that number three scale advantages can cascade That’s the monger idea Number four diseconomies of scale big company disease is underrated and definitely under measured. And then number five, you really need to separate barriers to entry from competitive advantages. And when you do that, what it lets you do is measure it much more exactly and not in this fuzzy way, which is I think the problem with scale advantages is an idea. It’s kind of fuzzy. Okay, that is it for the concepts and content for today. As for me, it’s been a pretty good week, work in a way. I’m heading into China in a week. Going to Hangzhou, I don’t know if I mentioned this before. I’m teaching at Alibaba University in Hangzhou, which is first time I’ve done that. I taught a lot in China for many years at Peking University in Beijing and then China Europe International Business School in Shanghai. I would say 10 years and eight years overlapping at the same time, both of those. And then I kind of stopped a little bit before COVID, like the kind of the year before COVID. I was a little tired of it, because your kind of teaching the same stuff. I think I needed a break and then COVID hit and it’s kind of, I taught a little in Chulalongkorn in Bangkok, which was fun, but I haven’t really done it since then. So, it was kind of the first step back into that. yeah, I was kind of interested in this. One, Alibaba is super fun to hang out with. People are really smart. They got a lot going on and it’s not really students, it’s entrepreneurs. They have courses and things when they’re trying to. get people more comfortable doing things, you know, basically online using e-commerce. So, you’re teaching entrepreneurs and small businesspeople, you know, how to win online or how not to lose and things like that. So that’s the first one that I first time I’ve done that. I’m kind of looking forward to that. So yeah, I’ll fly in and do that. And then of course, Hangzhou, you know, there’s some cool tech companies in Hangzhou. So, I’m going to visit a couple of those. I think I’ve given up trying to reach deep seek. I mentioned this before. We found the building and took pictures in the lobby and I looked in the Family Mart downstairs to see if maybe the CEO was there getting some food or something. But nope, no luck. It was a little pathetic but also kind of fun. yeah, Deep Sea, probably not going to happen. But there’s a lot going on in Hangzhou. So, I think I’ll talk about that. That’s a really interesting city, actually, Hangzhou. So, I’ll be there a couple days and that’ll be fun. Yeah, that’s kind of it for me. I don’t really have any TV recommendations or anything. Oh, you know what I watched, which I don’t recommend? Too hot to handle Spain. It’s awful. It’s just the worst. It’s like, you know, really attractive people all hitting on each other and you know, the whole thing’s fake and stupid. But it’s also kind of intriguing. I literally, so I watched like a couple episodes. I literally felt the same after like eating a box of donuts. Like you have one donut, it’s good. Two, it’s good. If you eat like three or four, like you really regret the whole experience afterwards. Like that was not good. I don’t feel good. I was dumb. It kind of feels like that after watching two episodes. So, I’m like I shouldn’t have watched any of this. It’s not good. So anyways, give it a shot if you want, see what you think. it’s, yeah, I don’t know why. Yeah, we’ll call that a non-recommendation. But it was interesting. I’ll give it that. Not good, but interesting. That’s how I’d put it. Anyways, okay, that’s it for me. I hope everyone’s doing well and I’ll talk to you next week. Bye bye.

———

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.