This week’s podcast is about economies of scale.

You can listen to this podcast here, which has the slides and graphics mentioned. Also available at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is the link to the TechMoat Consulting.

Here is the link to our Tech Tours.

Here are the 5 things everyone gets wrong:

1 – Not breaking economies of scale into its multiple types

2 – Overlooking the Negative Impact of a Non-Circumscribed and / or High Growth Market

3 – Not Understanding Minimum Efficient Scale, Indivisibility, and Scale Differentials

4 – Impact of Digital Disruption

5 – The Need for Demand Side Competitive Advantages

———-

Related articles:

- 7 Things Everyone Gets Wrong About Economies of Scale (Based on Fixed Costs) (Tech Strategy)

- GenAI Playbook (Step 3): How to Build Barriers to Entry with Intelligence Capabilities (9 of 10) (Tech Strategy)

- Why ChatGPT and Generative AI Are a Mortal Threat to Disney, Netflix and Most Hollywood Studios (Tech Strategy – Podcast 150)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- Economies of Scale

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- n/a

———transcription below

Episode 235 – Scale.1

Jeffrey Towson: [00:00:00] Welcome, welcome, everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is the Tech Strategy Podcast from Techmoat Consulting. And the topic for today, five things everyone gets wrong about economies of scale. So today will just be some theory, but I think fairly useful. This is a topic everybody talks about and usually doesn’t get that right.

There’s a lot of not complexity, but you have to break it out into several things to really understand when economies of scale is really powerful, which it can be, and other times where it’s not nearly what everyone thinks it is. So, I’ll give you sort of five things I think people get wrong pretty quickly.

Okay. And let’s see. Standard disclaimer. Nothing in this podcast or in my writing or website is investment advice. The numbers and information [00:01:00] for me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment legal or tax advice.

Do your own research. And with that, let’s get into the content. Now, obviously the concept for today is economies of scale, which,, this is kind of the go to competitive advantages for,, maybe it’s number one in terms of what people talk about and try to achieve. And it basically falls out of the idea of.

of look, in business, getting bigger gives you an advantage over smaller rivals. And it actually can play out in lots of ways beyond just what I’m going to talk about, can play out in terms of expertise in the company. It can play out in terms of you’re less susceptible to volatility,, disruption., if you’re a little plane flying 10 feet off the ground.

You’re a lot more stable than a big 747 in the sky. Turbulence [00:02:00] isn’t as big a deal. Having a product go bad is not as big of a deal. There’s a lot of advantages to scale. As I’ve talked about before, there’s, there’s some pretty good disadvantages to scale, bureaucracy, politicization,, complexity becomes too difficult, and there’s generally a sweet spot where companies get to a certain size and they get all the advantages but the disadvantages don’t kick in yet.

When you get too big, usually you get sort of broken up or a smaller competitor takes part of your business, things like that. I’m going to talk about the advantages. One category advantage is what we’ll call economic and competitive advantages. Not a lot of the other stuff I just mentioned. Okay, and also one other advantage.

sort of clarification. We’re not talking about economies of scope. Economies of scale means we do one thing and we do it more than others. It’s a volume effect. When we talk about scale we’re talking [00:03:00] about volume and throughput. How much do we produce within a given period of time? Of usually one item or two.

two items when we’re talking about economies of scope, that’s when we’re talking about scale and throughput for lots and lots of items like Procter and Gamble. They may not have scale advantages in any product line, but their whole suite of products that have similar characteristics will get them scope advantages in things like marketing and negotiating with retailers and stuff like that.

Okay. We’re just talking about economies of scale, mostly about the competitive and economic side. Advantages of that come. All right, so let’s just get right to it. Number one. What is something that people get wrong about this pretty frequently? Big one. Number one. There is more than one type of economy of scale.

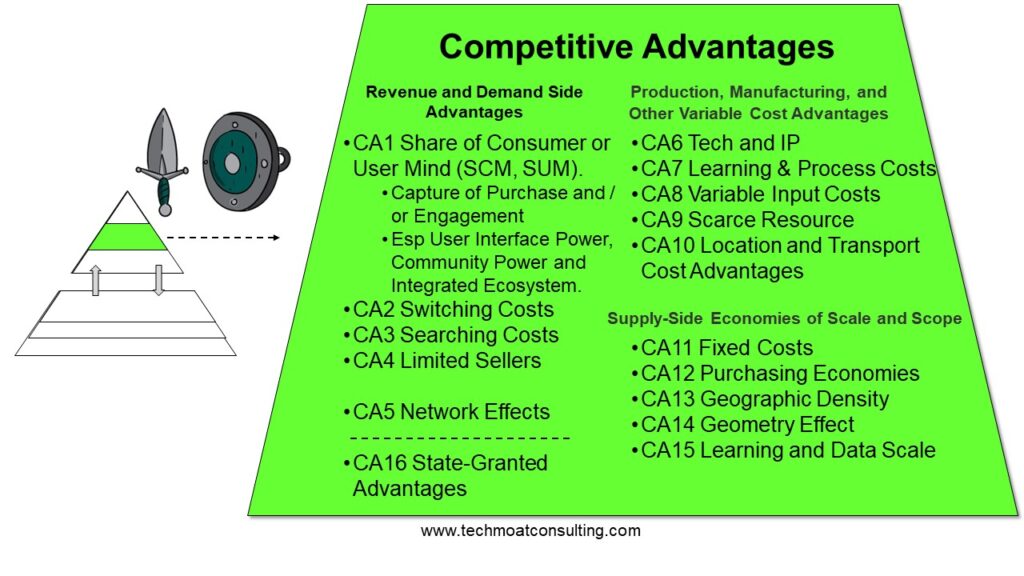

In fact, there’s several and for those of you who sort of follow my books, I generally break these [00:04:00] into five different types,, which I label CA11, CA12, that’s competitive advantage., so we’re talking about advantages versus rivals who are smaller than you. If a rival is your size, you don’t have this advantage.

So, Coke doesn’t have this versus Pepsi, but it has this against lots of smaller companies. Alright, so the five I generally talk about are fixed costs. There is some significant portion of your ongoing expenditure, which can be an operating expenditure, but it can also be things like maintenance capex. or necessary upgrades, which would also be a type of Capex.

We generally don’t consider growth Capex in this category. So, if we’re looking for what the fixed costs are, which would be operating and capital for, let’s say, I don’t know, Vodafone, a big mobile carrier. Well, we’d look at the big, fixed costs [00:05:00] within their income statement, which would be things like maintenance of the network, marketing expend.

Well, marketing can be kind of variable., R and D. But we would also look at their operating capex. So, what do we need to maintain the current network? And we would also have to look at upgrades because it is kind of accepted that mobile networks have to keep upgrading their capabilities. So, we wouldn’t really consider that growth capex.

We’d sort of call that a necessary upgrade. So, we look at fixed costs and A big mobile network has an economy of scale based on fixed costs advantage over a smaller network. They can outspend them in these areas., okay. Number two, CA12, purchasing economies. This is when, because we are bigger than a rival, we can get a better price on a key input.

Doesn’t mean we can get cheaper lawyers. That doesn’t really help us [00:06:00] strategically, but it does mean, like, let’s say you’re a health insurance company. The big advantage of a health insurance company is negotiating doctors and hospitals to build your network. Well,, if you’re United and you have a massive presence in the U.

So, you can negotiate a better term. That makes your health insurance cheaper. So, purchasing economies, big deal. This is what Walmart is based on., they go to China mostly and they negotiate really cheap things. And then what is their primary pitch to customers? Everyday low prices. So, there are a lot about purchasing economies.

So are a lot of the big box retailers., number three, geographic density. This is when we start talking about logistics networks. This is when we talk about things like grab and doing food delivery. And this is when the. The only volume throughput advantage we have over a smaller rival is the number of orders or the number of orderers in a certain [00:07:00] geography.

So, we’re looking for density of orders. And what happens is You basically can drop the cost. So, if you are FedEx, and you have tremendous geographic density, let’s say in the eastern United States, which means you’re getting lots and lots of orders, lots and lots of deliveries, you can basically capture lots of cost savings.

, you can batch your orders, you can place them closer to certain clients because you have more orders. So, you put them in closer warehouses. If they’re closer, it doesn’t take as much transportation costs. You can buy bigger trucks. You can have more airplanes., geographic density is one of these ones where you can see that you have a density advantage, but how you capture the cost advantage, it’s actually kind of tricky.

And what they end up doing is they end up combining with their order density with lots of sort of machine learning tools that are good at [00:08:00] squeezing out tiny savings. This is kind of what if you ever look at grabs sort of management talks, they talk a lot about how they’re capturing cost efficiency based on geographic density and machine learning.

That’s kind of what they’re using. That’s number three. Number four, we call geometry effect. I’ll put a list in the show notes of these by the way. Geometry effect is kind of more like assets. If you’re a, I don’t know, petrochemical facility, water tanks, if you have larger water tanks or fuel tanks or whatever, or larger pipelines, you actually get a scale advantage from the geometry of the structure.

Um, if you build a bigger water tank than your competitor, because you have more business,, The square meters, which would be the two-dimensional metric, increases slower than the three-dimensional network, which would be, I’m sorry, metric, which would be [00:09:00] volume. So, as you buy, build bigger and bigger water tanks or buy them, you have to spend, you basically spend less and less on the steel and you get more and more volume.

We can see this in things like airplanes. Bigger airplanes, generally speaking, fit more passengers, but the costs, at least associated with the cabin, which is the geometry we’re talking about goes up slower. So, in a lot of businesses, actually, geometry is kind of a big deal in terms of scale. A lot of physical businesses, that’s actually a kind of a thing.

Factories, you see this within factories all the time., and last one,, learning and data scale. Now this is what I’m still kind of working on., when does learning, adaptation, and data become a competitive advantage? Where larger companies better than a small one? I think data we can see today. We can see when certain companies have more data than others.

Let’s say you’re doing [00:10:00] risk analysis for insurance policies If you have more data Proprietary that others don’t have you can generally price things better That’s Buffett’s invested in a couple companies like this over the years that I’ve looked into Learning I’m still trying to figure out when if you are bigger than a rival you can learn faster and better and translate that into Gains, I’m still working on that one.

Not Totally sure. Anyways, those are the five. That would be sort of the common thing I think people get wrong., you need to know what you’re looking at. And we see,, that list, I didn’t think that up. I basically reverse engineered a lot of Warren Buffett investments over the years. That’s how I kind of got that list.

Okay., number, let’s go on to the next one here. Number two. Now the number two thing I see people getting wrong all the time is they overlook the negative impact. Of [00:11:00] markets that are either high growth or not circumscribed, not circumscribed, meaning there’s no clear fixed edge to the market,, that others can’t sort of jump into.

So, like highly innovative markets tend to not be very well circumscribed because they’re keep changing and what you can do in them keeps changing., markets where you can jump from one ancillary market to the next. tend to be not circumscribed. You can go from selling e commerce products to e commerce services pretty easily, which companies like Alibaba have done.

You can go from e commerce markets to doing content. So,, that would be sort of non-circumscribed. There’s not hard barriers. to the market itself. My favorite example of this is being the one hospital in a mountain town. Now, if you are the only hospital in a mountain town, far away from [00:12:00] everything else, you have a very circumscribed market because people get their health care locally.

And if you’re,, an hour drive away from anyone, okay, you’re, you’re circumscribed geographically. Now it also helps if there’s limited demand in that market., like if it’s not a growth market. Now if you have a big tourist town in the mountains, you can have growth. But if you have a non-tourist town, not only are you circumscribed by geography, but you don’t have high growth.

Okay, why do both of those things matter? Growth, demand, demand. Non growth and circumscribed,, it basically means you don’t have a lot of room for another party to jump into your market and get to your scale. There’s not enough room,, the market’s not growing. So, if you’re going to jump into a market that’s not growing and there’s an incumbent who has a scale advantage, the only way you can match them in terms of scale is by [00:13:00] stealing their customers because there’s no growth.

Well, that’s very hard to do. Stealing customers is a lot more expensive. Or if it’s a very circumscribed market,, sometimes if it’s not circumscribed, like if you’re very good in content, but another party’s very good in e commerce, because the boundary is sort of fuzzy, you can be big in one and jump into the other.

Okay, mountain town, you can have geographic circumscription., you can have functional product level. But generally speaking, we are, anytime you have those two situations, your economies of scale are less defended.,, I like businesses that are geographically isolated, like a hospital in a mountain town, a supermarket on an island.

, those scale advantages tend to be pretty good. I like products that are highly specialized or that serve sort of niche and [00:14:00] specialty markets like Etsy, the e commerce company,, they focus on these handmade and vintage goods., that’s kind of nice, specialized niche, both of those things.

There’s just not a lot of room for someone to jump in and match you in terms of scale and then if they’re no growth, okay, you got to steal. So that’s kind of number two., this is why I often talk about how I like strange little businesses. Like the animal analogy I use is, Like, I don’t like lions and tigers, I like porcupines and anteaters.

Like these strange, highly specialized businesses for highly specialized situations. An anteater is specialized, no it’s got the long snout, to get ants out of an anthill. Right? If you can have a scale advantage in highly specialized activities, very hard to break into that. So [00:15:00] anyways, that’s number two.

Don’t overlook the negative impact on economies of scale of a non-circumscribed market or a high growth market. Sometimes both. We see this a lot in digital actually. Okay. Number three. not understanding minimum efficient scale, indivisibility and scale differentials. So, it’s kind of three ideas that go along with,, basically economies of scale when it becomes an advantage.

Now what is minimum efficient scale? When you enter a market, if you want to be a viable competitor and there is a, or let’s say you’re a smaller rival and you want to be competitive against the incumbent or someone who has an economies of scale advantage against you. There is a minimum level of scale, minimum viable scale, minimum efficient scale that you have to get to [00:16:00] before you are considered a reasonable alternative to a typical customer.

Okay. If you want to jump into mobile networks, which have huge scale advantages, you can’t offer just a mobile network for New York state. You can’t even offer it just for the Eastern. You have to offer at least the U S from one from day one to be sort of viable and to have enough efficiency to get your cost structure, , In the area where it’s competitive now, minimum viable scale is sort of like, what do you need to offer so that customers will consider you that’s mobile network size minimum efficient scale is look, there is a number in the market where if you don’t get enough scale, your cost structure is simply not feasible.

You can be a smaller rival versus a bigger rival and you’re going to be an advantage, but you can still operate. [00:17:00] But there’s a level below that where you’re just not big enough to have any sort of efficiency on the cost side. Your costs are way out of whack., you can’t compete. So generally, what happens with minimum viable scale, you jump into a market, you have to sort of bleed cash and spend a lot on marketing to get to a scale.

That you’re a viable product for customers and you are in the realm of efficiency in terms of costs that you can survive. You won’t be competitive, they’ll still have an advantage on you, but you’re survivable, you’re viable,, you’re sort of efficient scale. So that’s how I think about it, minimum viable scale versus minimum efficient scale.

And I, I lump all this together into the market entry cost. What does it cost for you to jump into this market? Well, you’ve got to build your mobile network, but you are going to have to cover your operating losses until you can get to MES

and MVS. That can have an impact. If a market has a higher [00:18:00] MES, your economies of scale advantage can be more powerful. If the MES is very low, your economies of scale advantage is not as strong. Second idea, indivisibility. Indivisibility is when we have a fixed cost that we can’t break into smaller costs.

Now, for a long time, you could have an economies of scale advantage as a tech company on your compute infrastructure. Basically, you had to buy a bunch of servers and put them in your,, office, on premise. And you could have smaller servers and add them up, but it wasn’t too divisible., there was sort of a minimum.

It’s like building a car factory. Your kind of, that, that’s a big step. You can’t build half a car factory. You kind of got to build the whole thing. And there’s no way to divide it into pieces. Now, one of the things cloud computing did is it [00:19:00] basically made that compute fixed cost much more divisible.

Suddenly you could break it into pieces and only use it as you need it. Well, car factories It’s pretty much indivisible. What you want is economies of scale as an advantage in cost structures that are have a sort of high Indivisibility because that makes it even harder for someone to break in it makes them harder for them to ratchet up to your level So that’s sort of way think about last idea.

I mentioned scale differential whenever I look at economies of scale I look at the difference in scale between the leaders Usually the Giants and the Dwarves. Let’s say we’re looking at Coke and Pepsi. We would look at the scale differential between those two. Okay, it’s going to be pretty small in certain geographies.

It’s going to be pretty small like the U. S., but we can then look at the scale differential between let’s say Coca Cola and Dr. Pepper. We can look at those. I always like [00:20:00] to know those two numbers. What is my scale differential versus direct cost? Rivals and smaller rivals, which I usually call giants and dwarfs.

And that’s a good number to track over time. If you had done this in the 70s, you would have seen that Pepsi was systematically decreasing the scale differential with Coca Cola. And Coke didn’t really wake up to this fact until the 80s. And when they saw suddenly Pepsi was as big as they were, almost they launched a price war and a marketing spend war against them.

And it didn’t work. Because it was too late. Once they get to your size, your advantage is gone. They should have done it 10 years earlier when it would have had power., so that’s sort of number two here is don’t underestimate or I’m sorry. Yeah. Don’t underestimate. Sorry. If you’re going to understand economies of scale, you got to understand minimum efficient scale, indivisibility and scale differentials.

All right. That’s number three. [00:21:00] All right. Number four. Number four is, is sort of underestimating the impact of digital disruption on scale-based advantages. This is kind of an area obviously I spent a lot of time on. Digital disruption, new tools, new business models, new technologies can really usually I mean, this is I kind of joke that like Silicon Valley is in the business of disrupting incumbents whenever they do these new techs and new tools and new business models, they don’t you undertake a certain amount of technology risk as a company to do this.

They don’t like to take on technology risk and market risk. They don’t want to create a new tool that nobody’s used before. So, what they like to do is target a proven market with no market risk, and then use their tool to disrupt the incumbent. So, Silicon [00:22:00] Valley, all these things, it’s like when Airbnb came in, they were targeting hotels.

When Uber came in, they were targeting taxis. So, a lot of the digital disruption stuff is about taking down the scale advantages of incumbents, and this is actually what digital is really good at. It’s about letting smaller companies do the things that only big companies have been able to do in the past.

It’s kind of like Jack Ma’s mantra. He creates tools for small merchants that lets them do the thing that big merchants can do, like sell across a big country. Okay, often when digital disruption comes in to an incumbent, the number one target is usually barriers to entry. If you want to create a tech company, you got to buy a bunch of on-premises service.

Well, cloud compute, wipe that out. If you want to make videos, animated movies, well, you got to have the tools to do that. What is that? That’s [00:23:00] generative AI. It’s targeting the scale advantages of Hollywood. So, we see this all the time., now when I look at sort of digital disruption hitting economies of scale, number one thing I look for is sort of.

, this, this balance between tangible and intangible assets. Generally speaking, economies of scale tend to be very powerful in fixed assets, intangible things like we have a big, huge factory. When you have scale advantages in intangible assets like algorithms, data, software, you are generally more susceptible to change.

So, my favorite type of business model is a mix of digital and tangible, like e commerce. Yes, you can disrupt us on the user interface and the content we provide quickly, but you still have to replicate our [00:24:00] 1, 000 logistic centers across China. That’s harder. So, I look for that., I look for this idea of connectivity and distributed production.

One of the things digital is very good at is connecting you to others much more than traditional business. Sometimes you can start to connect people and you can sort of mimic the economies of scale of a big company like an example of this would be logistics networks in China Now logistics networks have a big scale advantage.

You have to build all these warehouses across a huge geography You have to have a lot of trucks. You have to have a lot of airplanes, They do that in house at FedEx, although they’re not in China domestically But what if we can sort of do virtual warehouses or ghost warehouses where we provide the software and the connectivity and Anyone with a warehouse can become part of our network and just sort of a plug and play model [00:25:00] Suddenly we’re starting to basically work with external parties to replicate a massive logistics network without having to do it ourselves That’s pretty cool.

, open source is kind of like this. Anytime you can lean into connectivity and basically do production that is distributed rather than in house, you can devastate economies of scale pretty significantly., the third bit here is, this is a McKinsey term, they call it the three D’s, disintermediation, disaggregation, dematerialization.

It’s a terrible mnemonic, it’s impossible to memorize. Basically, disintermediation is when we can go direct to customers., if there’s someone between us, like we’re a farm in China and we want to sell our goods to market, we’ve got to go through this tremendous distribution network, which is really inefficient in China.

But, or I can go on JD or Pinduoduo and sell [00:26:00] my farm goods directly to customers. Disintermediation, which is enabled by digital connectivity. Disaggregation, that’s kind of like indivisibility., that’s when we can take something, a large asset, and break it up into smaller pieces. Same idea. And then dematerialization.

That’s when we can take a physical asset and make it virtual. You could argue that the on-premises service are like that., Hollywood studios, which you used to have to do in person with cameras and sets. Well, now you can just create them on software and you can make videos without sets. Anytime you can dematerialize.

Pretty good. Anyways, that’s kind of how I think about that one. The impact of digital disruption on economies of scale Pretty important and that’s kind of where I live. I look at stuff like that because I think people get it wrong So that’s kind of my area. Okay last one number five people [00:27:00] overlook the need for demand side advantages If you are going to have economies of scale on the supply side, you have to maintain a scale differential between you and your smaller rival.

Our throughput is a thousand units per week. Their throughput is 200 units per week. Therefore, we have various cost advantages that come out of that. Okay, I’ve got to prevent them. from decreasing the scale differential. And I mentioned two ways they can do that. Like if you’re on a high growth market, it’s much easier.

If you’re in a market with sort of fuzzy boundaries or innovation, it’s easier. But the most common way to do it is, there is a demand side advantage as well that makes your customers never switch. Now think about that. If I have high switching costs, let’s say I’m a SaaS program [00:28:00] and I have economies of scale on the supply side on R& D.

and my tech platform. I also want switching costs on the demand side because suddenly I mean over time People can steal your customers. They can slowly whittle them away like coca cola I’m sorry, like Pepsi did to coca cola and they can decrease the scale advantages Unless you have them locked in on the demand side as well, then it’s much harder to make that gap go away so generally speaking Yes, you want supply side advantages.

That’s, this is why I think Hollywood is in such big trouble. All of their advantages are on the supply side. They’re good at production of TV shows and movies, and they’re bigger, and this stuff is expensive, and they have scale advantages. Now, they also have some distribution stuff, but they generally have no hold on customers.

They can’t force you to go watch their new movie, and as [00:29:00] these tech tools come in that make production much cheaper, and anyone can start to make movies now, you’re going to see that that’s all they had and they have no hold on the demand side. Now a better scenario is like a SaaS company like Microsoft Office.

Or not Microsoft, let’s say Microsoft Teams, where you’re using their software to run your business. They have like as an ERP system. They have unbelievable power on the demand side. Nobody likes to switch their ERP system. And then in addition they have economies of scale in R& D, IT, and basically Salesforce.

Those two together much more powerful. And that’s, and then if you have network effects like Alibaba, it’s even more so. So yeah, you always need to think about demand side advantage. And I used to have a professor at Columbia business school,, Bruce Greenwald, and he would always say like. You don’t just want economies of scale over the long term.

, they tend to get [00:30:00] taken down either by someone whittling away your margins or your market or by disrupting you with tech. You want economies of scale on the supply side plus demand side competitive advantages like switching costs. Those two together, that’s the power, which I’ve found to be basically true over time.

Anyways, that is my five. I hope that is helpful. Not too long today., I’ll put them in the show notes, but, yeah, basically look, there’s more than one type of economy of scale. There’s four or five. Two, you don’t want to overlook the negative impacts on economy of scale of having a non-subscribed or a high growth market.

, you got to understand minimum efficient scale, indivisibility, scale differentials. Don’t underestimate the impact of digital disruption on scale. It’s like their favorite target. And then number five, you need demand side plus supply side competitive advantages, especially economies of scale., it’s much more powerful. [00:31:00]

Okay, and that is it for the content for today. As for me, I’m having a spectacular week. I’m,, I’m in Paris,, for about a week. Just great. I’m enjoying it immensely., meeting lots of people, having a lot of fun, getting up early, going down to get baguettes, taking walks in the park. It’s, it’s one of my favorite places.

Arguably it’s, it’s this and Southeast Asia are my go-to places in this world. So, I’ve been in a spectacularly good mood all week. It’s cold, which I’m not good at, but, yeah, fantastic. Anyways, I’ll be here till the end of the week., meeting a bunch of people here. If you, if you’re in the region, you want to talk,, give me a call.

I’m, I’m doing lattes all day long with groups having a great time. So, if you’re in the area, give me a, give me a ring, but that’s it for me. And I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.

———-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.