This week’s podcast is about the external view and the importance of base rates. Berkshire-invested Kroger supermarkets is a good example of a company that can really be viewed externally.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes and Google Podcasts.

Here is my new book:

Common metrics for base rates:

- Sales growth

- Gross profitability (gross profits / assets)

- Operating leverage. Change in operating profits relative to change in sales.

- Operating profit margin

- Earnings growth

- CFROI

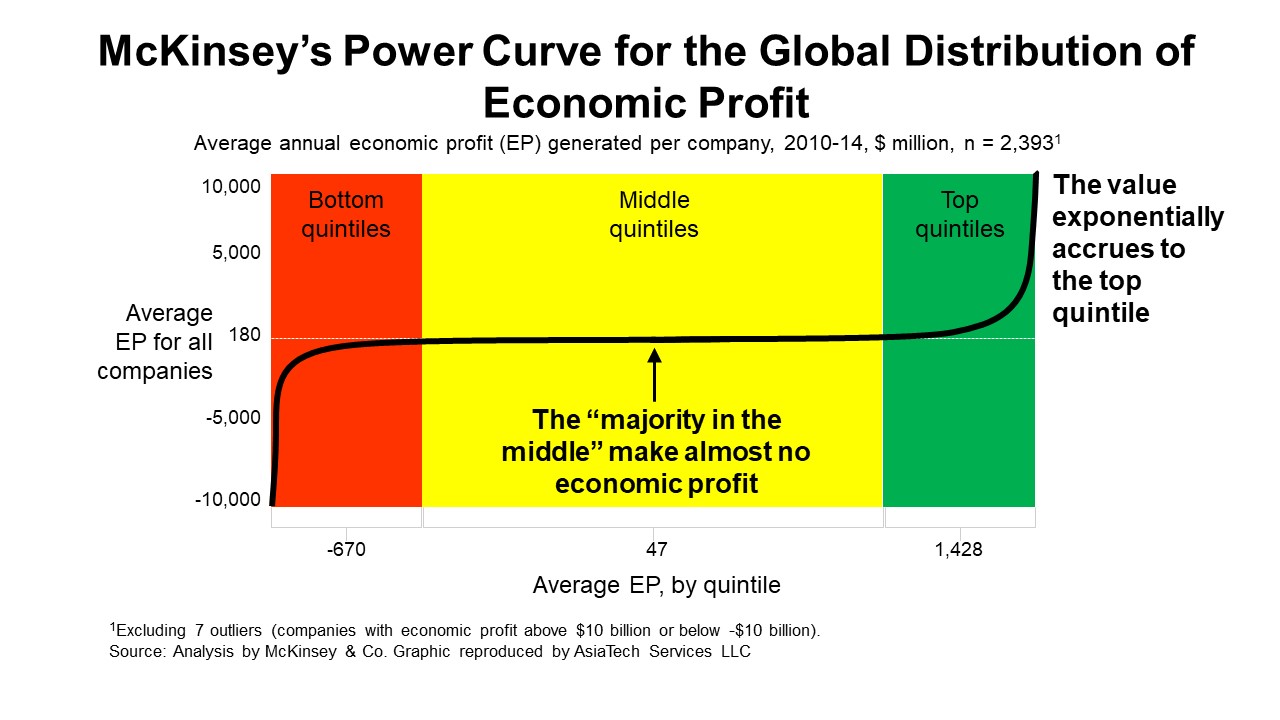

Here is the McKinsey Power Law for economic profits

Here is the McKinsey book Beyond the Hockey Stick.

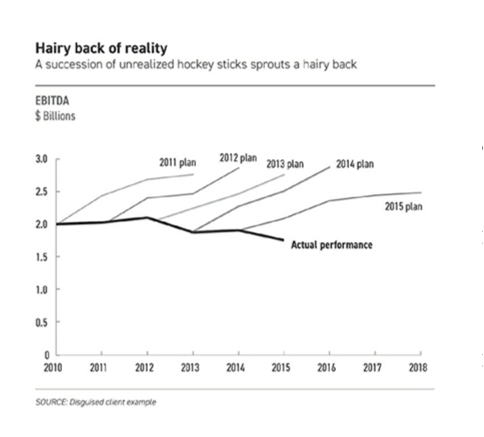

Here is the Hairy Back graphic from McKinsey

———

Related articles:

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- External vs. Internal View

- Regression to the Mean (average / base rates, rate of regression)

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Kroger

Photo by Peter Bond on Unsplash

——-

I am a consultant and keynote speaker on how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a consulting firm specialized in how to increase digital growth and strengthen digital AI moats. Get in touch here.

I write about digital growth and digital AI strategy. With 3 best selling books and +2.9M followers on LinkedIn. You can read my writing at the free email below.

Or read my Moats and Marathons book series, a framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

Note: This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

—–Transcription Below

:

Welcome, welcome everybody. My name is Jeff Towson and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, Kroger markets and why base rates are so tough in digital, part two. So I really wanna touch on two things. The first is totally outside the field of digital and Asia, which is Kroger, which is a US supermarket chain that Berkshire Hathaway has been buying. this year and in the last couple months, buying shares. So that got my attention. And I’m not gonna go too much into the company other than to explain it a little bit because it’s kind of not relevant to Asia tech. But it does tee up an issue that I’ve talked about before, which was base rates, the external view, regression to the mean. And I talked about that in podcast 61, which was sort of why base rates are so difficult in digital. and about square. So, I mean, I wanted to sort of do two things in this podcast. One is to tee up a company that maybe is worth looking at. If Berkshire’s buying it right this year, this quarter, probably worth taking a look at. And two, this idea of the external view and base rates, which is incredibly important, but hard to do in digital. So I want to sort of finish up that as a concept. So that’ll be the sort of value goal for today. What other? My book is out. You can see the link in the show notes. That’s Motes and Marathons Part 1, which is basically a set of frameworks for measuring the competitive advantage of a digital business. And this could be a digital native, like a square, or it could be a company that is going digital, like a Walmart. Same thing, same frameworks. So that’s the point of that. $6 available on Amazon. Link is in the show notes. And I guess one current topic to touch on quickly, SenseTime, Chinese AI company, which does a lot of facial recognition in China. Well, I mean, they’ve been struggling to go IPO got for like a year and a half. They tried to go IPO in Hong Kong, where it was the US first, and then they switched to Hong Kong, and then they got delayed. It’s kind of been, we’ve been waiting for this IPO for like a year plus. Anyways, They’re on the verge of this right now, but, and they are within the newest wave of China digital giants. The wave we always talk about is kind of 2000 to 2013, which is like, let’s say, ByteDance-ish, DD, those companies. But the newer wave starting, let’s say, 2015, a lot of those are AI companies. I mean, You could really call ByteDance an AI company at its core. So this whole next wave of Chinese digital giants are probably gonna be AI focused. And so SenseTime is one of those. They’ve been around for a while. They do, you know, the algorithms that let you know what someone is doing in a video. It’s mostly about people, but it can be cars. And, you know, obviously there’s, you can do security for that. But big surprise, they have a lot of government contracts in China. Anyways, that’s kind of, you know, I’ve been having my eye on this company for quite a while. I think it’s gonna be important. I think there’s a bunch of these AI companies. However, news out of the US, maybe, maybe not, that they’re gonna be added to the blacklist out of the US. There’s a couple of lists you can get on in the US, like the entity list is what Huawei got on. And that has to do with export. But the Department of Defense has its own list where if they feel like a company is working with a foreign military of some type, there’s a couple lists that can come out of the Department of Defense or the Commerce Department. There’s a couple of these. And they can have sweeping ramifications, which is what happened to Huawei, or they can be limited in the sense that no American citizen or company can invest in them. Alright, so there’s a spectrum there. This is floating around the last couple days. I’ll give you an opinion on this. I don’t know what they’re doing government wise with China. You know, no one will ever know. That’ll all be contracts filed in a drawer, who knows? I think if the US government is going to continually use this lever, it’s problematic because these AI companies are gonna be in everything. It’s not like Huawei where there was only two telco companies out of China that were, let’s say, concerning for the US government. ZTE and Huawei, that had some impact, but it was two companies. There is a long, long list of AI companies coming out of China, and a lot of them are going to have government contracts. So this could really be opening a much larger door between the US and China in their, let’s call it, tech war, even though it often plays out within trade tariffs and other things, it’s usually, and it’s increasingly being played out in the financial system. Basically the trade rules and the financial rules have been somewhat weaponized. But usually the focus of that is technology, it’s not finance or trade. It’s just what the tool is being used. So I think that’s opening a much larger door. I’m sort of paying close attention on whether they’re gonna go down this path. And also these tools are much easier to export. It’s one thing to export base stations from Huawei that happened to have semiconductors that were out of TSMC. You can kind of check that and see if they’re being used in London. It is very hard to audit where software algorithms are being used because all you need is a connection back into China and you can run the algorithms. So it’s a lot harder to control the spread of technology when it’s software versus a chip or a base station or a smartphone and whether it has Android or not. Anyways, put that on your radar as something to pay attention to. We’ll see what happens in the next week. Okay, with that, let’s get into the topic for today. My standard disclaimer, nothing in this podcast or my writing on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information from me and any guests may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed by me may no longer be relevant or accurate. Overall, investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research. Oh, one last thing I didn’t mention. For those of you who are subscribers, I sent you part one and part two about A&E Logistics. It’s bad term, A&E. It’s a Chinese word, an nung, but it’s a really interesting company, not in the sense that I think it’s maybe a great investment. It may or may not be. But I think it’s a great example to understand logistics networks, physical networks, and why they can be so powerful. You know, FedEx, DHL, we do see these global giants based on this. So that’s kind of been on my shortlist for a while. I sent you part ones and part two. I’m going to send you part three in the next day. I think this is pretty good. Like I’m feeling good about this. Like I’m trying to impress you a bit on this one. I think the framework I’m gonna give you for taking apart this company really nails it. Like I feel good about this one. Sometimes like, hey, I think that was pretty good, maybe not so good. I think I really got this one nailed. So anyways, that’s on the way for subscribers. If you wanna be subscribers, go over to jefftausen.com, sign up there, there’s a free 30 day drop. Okay, let’s get in the content. Now the two concepts for today are the external versus the internal view. and regression to the mean. Pretty common discussed topics in investing but they’re important, super important. So those will be the two ideas you can find them in the concept library. And let me kind of start with Kroger. Now Kroger is just a supermarket. Like no offense to you know people who like Kroger, it’s a supermarket. It’s been around since 1883 in the United States. You know. 2700 supermarkets across the United States. They’re under different brand names, but it’s basically, they’re all selling pretty much the same stuff, which is we wanna be your grocery store, your local grocery store, that is sort of a one-stop shop. And we see this business model all the time, not business model, we see this value proposition to consumers all the time. in some retailers like Walmart and whatever, which is like, we’re gonna offer you a very, very wide selection of products such that there’s no reason to go anywhere else. Oh, it’s usually two things. It’s like, we’re gonna offer you a very wide selection. It’s gonna be relatively close to your house, and we’re gonna have the lowest prices for reasonable quality, acceptable quality, and therefore, you have no reason to go anywhere else. One stop shop. Walmart is a much larger spectrum of SKUs and they drive the low cost thing harder. You know, everyday low pricing, that’s the Walmart slogan. Costco took that and Sam’s Club took that even further, which is like, look, we’re gonna have smaller items, but we’re gonna be so cheap that you buy things in bulk. And we’re not even gonna make our money on selling food, which they really don’t. They make their money on membership. you sign up and they make their money there and they basically pass on the food to you at negligible gross margins. Okay, so let’s say we’re looking at a spectrum of this business model. Costco, Sam’s Club is the more extreme version. Dial that up one level, we’re probably at Walmart, super stores, hypermarket, well, super stores. We dial that up a little bit more, we start to get to supermarkets and hypermarkets. They tend to be a bit smaller. and they tend to focus on groceries. So this is your one stop shopping, but as a supermarket, you know. So general merchandise, organic food, nutritional food, perishables, things like seafood, meat, dairy. And why is that different? Well, because most people go to the supermarket a couple times a week. You may not go to Walmart every couple of days, but when you’re… cooking dinner and things like that, you go. So the higher frequency, they tend to be a little closer to your house and they tend to be smaller than say the Walmart superstore, which is further away. Now that would be sort of your standard supermarket that has evolved over the US in 100 years. They’ve added a couple things to that. They’ve added pharmacies. So if you look at the 2,700 supermarkets under the Kroger, let’s say, system distribution, I won’t call it a platform, 2,200 of those have pharmacies. They’ve started to add fuel centers, which may or may not be profitable. About 1,500 of them have fuel centers, so you can go out and get gas while you’re there. And depending on their strategy, they may really subsidize the gas, which is a great, hey, we can get gas a lot cheaper. Let’s go there when we go shopping and we’ll fill up. And they’ve been building this for a long time. Now, one of the things we see with supermarkets as a massive retail footprint, which is what they are, that we don’t necessarily see with, let’s say, Walmart, is we start to see them not just stocking and selling, but we also start to see them doing production, where they will often have their own food production centers. These might be bakeries. They can actually be coffee roasters sometimes. It depends how, like if you go to Whole Foods, they have quite a lot of sort of production they do themselves because they’re more of a premium band. Kroger’s, it’s much less bakeries, things like that. So you do get a little bit more, what’s called vertical integration, where yes, they’re a retailer, but they also do some manufacturing and processing of food. Probably the other thing to think about with a company like this and this is just kind of big retail 101 I’m not telling you anything particularly Compelling here. I don’t think and they have a couple store formats. They do they have You know, they have kind of their combo store, which is mostly we’re selling food and drugs Pharmacy, then they’ll have the multi department store, which is a bit bigger. Well, I’m sorry shouldn’t say bigger, but I Bit larger than the combo store. They might offer some departments there that they wouldn’t offer. Like maybe they’ll have more general merchandise, apparel, maybe they’ll have electronics, automotive, toys. So you’re starting to look more like a superstore. You could have a marketplace store, which would be smaller than a multi-department store. And then they do have some sort of what they call price impact warehouses. that gets you closer to a Costco model. So they got a couple formats they’re doing, but overwhelmingly we’re looking at their combo store, your big supermarket, that’s mostly what they’re doing. Now the last factor to kind of keep in mind when you’re looking at a model like this is private label. Right, like private label’s pretty awesome. A store like Amazon will get criticized for doing private label all the time, because you know, People build their online stores there, backpack, makeup, shoes, and then Amazon Basics will offer their own version of a backpack or an all birds shoe, and it looks pretty similar, but it’s a lot cheaper. And you know, they get criticized for this, and this has largely been banned in India. India now says you can be a marketplace platform for other merchants and brands, or you can be a retailer, but you can’t be both. But Amazon will say something like, look, Stores like Walmart and every other retail have been doing this forever. Walmart has its own brands on the shelves of cola or bread or whatever, right next to the Coca-Cola’s and whatever. It’s a very common strategy. It’s a smart thing to do. So e-commerce companies do do this. Some of them like Amazon do, others don’t. So Kroger has a big R brands, R brands. About 15,000 different private label products that they put in various tiers. The private selection, which is premium, the Kroger brand, which is the vast majority, the Simple Truth brand, which is organic. So they’re kind of playing all that. And that’s a pretty standard big supermarket retail model. And yeah, so. Big operation, 465,000 employees, including part-time. They serve nine, 10 million customers every year. And they’ve got a lot of union and 350 union agreements. So it’s complicated. Okay, so here’s my so what, why am I talking about this? Because I’m trying to figure out why Warren Buffett has been buying this company. Oh, and if you look at the financials. They basically look like your standard supermarket in the US financials, which are pretty good revenue in the case of let’s say 2020 sales at Kroger, 132 billion US dollars, up from 122 billion in 2019 and up from 122 billion in 2018. So What’s interesting is the revenue is relatively flat, but then 2020 hits, pandemic year. What happens? Their revenue goes up. People forget when all the restaurants and everything shut down, people still have to eat. It turns out selling daily necessities like food did quite well if you weren’t a restaurant. People still buy. They just did a lot more cooking at home or they had it delivered. And they had an online channel, which they ramped up a bit. So we’ve seen that in a lot of, you know, this sort of company over the last 2020. So, okay, the revenue took a $122 billion up to $132 billion, $219 to $220, nice. But then when you look at their sort of merchandise costs and all of this and their rent and their depreciation and amortization, their operating profit about 2%. And that’s pretty common, 2019, 2%, 2018, 2.6%. That’s pretty common for supermarkets. So that’s kind of when I started looking at this and thinking, when I look at this company operationally, not much has happened in 2018, 2019, 2020. This is a company where base rates and the external view are really important. And I’ll talk more about what that is. But this to me was a prime example of base rates and external. view as an approach to evaluating a company. And then the question would be like, okay, why did Buffett buy this? I’m not seeing any massive change in the operations. I’m not seeing it. You know, is it just the price was good? Was that it? Or was there some one-time event baked in here? Like, you know, there was some government assistance and some other things. The company’s been tightening up the hatches in terms of their working capital and managing inventory is really, really important. And if you want a great tutorial on how to manage LIFO versus FIFO inventory and how you account for that, read the Kroger 10K. They lay out their inventory management and how they account for the cost of it. And they lay out the return on invested capital really quite well. This is one of the better, if not one of the best written 10Ks I’ve seen. I suspect that has a lot to do with how they got Buffett’s attention. This is clearly someone who’s ever writing this company speaks his language in terms of business. I suspect that’s part of it. Anyways, that’s sort of a tee up to Kroger in the US. It’s worth taking a look at. It’s worth trying to ask yourself, is this a decent investment and what has changed in 2020 versus 2019 such that Berkshire was involved in ramping up? Because the operations don’t look dramatically different. They look pretty similar. And that gets me to sort of the topic for today. And I talked about Sun Art Retail, which was the hypermarket in China, which Alibaba bought. We really saw, and there’s a podcast for this, just look up Sun Art Retail on the company library. Their financials looked very similar. I mean, the revenue line looked very, I mean, it was the same. Like if you looked at 2018, 2019, 2020, their financials did not move at all in China during the pandemic at all. Now they’ve been purchased by Alibaba. So they’re sort of tied with the Alibaba ecosystem. That’s why I thought that was so interesting, but the financials look very, very similar. We look at SunArt, we look at Kroger. It tees up this idea of the external versus the insider view. and regression to the mean. And so that’s sort of the concepts for today. So now let me switch to that, but I encourage you to read this 10K and especially look for how they detail the accounting and cost structures for inventory management. It’s really well laid out. Oh, one last comment on this. They do have a digital initiative. And I did look at their digital initiative and how they described it and what they’re doing. And it wasn’t. well thought out in my opinion. In fact, I think that it’s really an interesting contrast because when they talk about their stores and inventory and management and sales and product mix, the description is outstanding. The language is very precise. The metrics they’re using are very good. And then when they switch to their digital, it is really half-baked thinking. It’s clearly not their skill set and they don’t know how to talk about it in my opinion. So they kind of mentioned, well, we’re gonna do personalization. We have an online distribution channel, which means you can order and then pick up. So a lot of these big retailers, the easiest thing for them to do was to put up a website and then say, order online and come pick it up. Pick up and go, not bad. And then they’re becoming more data-driven where they’re starting to personalize what you see on the e-commerce website to you. which they don’t do to you personally when you walk into the store. So this is really, if you look at my six levels of digital competition, this is the digital operating basics and it’s really basic. Like, you know, it doesn’t even compare to what we’re seeing in China. So, and their language and their thinking is not good. They’re not talking about entertainment and getting customer engagement and they’re not doing live streaming and they’re not putting their salespeople. They’re not doing anything we would see at the most basic departments to our supermarket in China. This is really primitive digital thinking. But I mean, it’s not terrible. It’s a reasonable first step. We’ll put up the e-commerce as an alternative distribution channel. We’re probably not going to ship much to the home because this is perishables and it’s difficult to deliver perishables in the U.S. It’s easy to do in China and other places harder in the U.S. So we’ll have pick up at the, you know. outdoor counter and as we get more data on you we will start to personalize the website or the mobile app to you. Fine digital operating basics that’s you know level five of my six levels but I’m not going to bag on them but yeah it’s not impressive and the contrast between that and how they talk about the retail operation is really stark. Anyways next topic. So what is the external versus the internal view? Now I talked about this in podcast 61 and I’ve written about it. You can just go to the concept library, click on it, you’ll see the past articles there. But it’s incredibly important. Actually in the podcast 61, I did say I would do part two. That was part one and I didn’t really get to it. So this is technically part two. I mean, it’s super important. And basically the idea is, When we analyze a company, whether you’re looking at the company or we’re looking at it as an investment, so then there’s gonna be other things you’ll look at like price. We can look at the company with the inside view versus the outside view, and we are heavily biased to look at the inside view. Now what is the inside view? Is we look at a company and we start to gather information about that company. Maybe we focus on an issue. What is their sales mechanism? What is their business model? I mean, most of the stuff I’m talking about is inside view. And then we start to sort of maybe extrapolate forward. Well, what is this company gonna do? And then from there, let’s say 70%, 75% of the attention is gonna be on this one company. And then we will start to probably make comparisons to other companies. Well, how does Kroger relate to SunArt? How does it relate to Walmart? we’ll start to make those comparisons, you know, that’s pretty normal, let’s say another 20 or 30%. And then we also kind of, the way our brains work, we will start to make connections between this company and our past companies we’ve looked at or we’ve worked at our own experience. You know, we tend to really rely heavily on our own experience, on frameworks that we like, on rules of thumb. This is all sort of inside. thinking and we are very hardwired to think this way. This is really how our brains work. We’re gonna look at the company, we’re gonna look at some competitors and maybe we’ll broaden it to the industry but we’ll also think about a handful of case studies and we’ll try and draw connections and lessons from those. The problem with this approach is it is data light. It heavily over relies on a small number of companies and a small number of case studies. And it really plays in to our inherent weaknesses of being overconfident and believing that we have skills. That is a pretty big problem. Most, I definitely have this problem. Now let’s contrast that, put that aside for a moment. And let’s say, look at the external view. An external view is, let’s look at all the supermarket companies in the United States in the aggregate, all of them. Let’s have a high level. industry-wide, deeply data-driven statistical approach to this. And let’s set aside our own information, our own experiences. We are going to look at a reference class, or what people call the base rates, for this thing. And then we will look at it. And within building an external view, you basically build a reference class of lots and lots of companies. And then you come up with base rates. for certain metrics. And in podcast 61, if you, well, I’ll put it in the show notes here. I’ve listed several base rates you should have in mind. Sales growth, gross profit, gross profits divided by assets, operating profit margin, earnings growth, cash flow, return on investments. These are standard base rates. And we will develop those for the whole industry. And it forces you to recognize, look, Most supermarkets in the US make 2%. They just do. So when you get really into this new novel, cool supermarket that’s going digital and the management’s hot and ooh, it’s got a great thing, and they say we’re gonna make 19% operating profits as a supermarket, you can get very lost in the internal view and the business model and why it’s stronger. But then when you switch to the external view, you’re like, look, every supermarket makes 2%. The really good ones make three. The lower ones make 1.5. Why do we think this is gonna be such an outlier? And it forces you to confront that. That’s really, really helpful. It’s just sort of a data-driven, non-personal approach. And, you know, let’s say this is also helpful when you’re thinking about your own career. Like, do I want to be a dentist in life? My brother’s a dentist, my father was a dentist, he’s retired now. You can do base rates for dentists. This is how much they make. It’s pretty obvious. Dentists don’t make $10 million a year. They don’t in the US anywhere. But they also don’t make 55. They make 200. Maybe if they scale up their practice and they’ve got a couple partners, maybe you’re in the hundreds higher than that. Maybe if you really scale this thing up and you got 20 or 30 hygienists working like a factory cleaning people’s teeth, something like that, you can get high. But generally speaking, when you look at the sort of… base rates, that’s what you’re looking at. And any dentists who says, I wanna be a dentist and I wanna make $10 million a year, not gonna happen. So that’s a really useful thing. But the external view is sort of, it’s based on the structure of the industry averages. It’s very data heavy. So now the trick with getting base rates is you need lots of data on hundreds of companies and you want the experiences of hundreds of executives. And that, in many cases, can give you clear numbers on the odds of success and what success looks like. Needs to be deep data, needs to be testable, and you really wanna use the external view to kill or correct the inside view. That’s kind of the idea. Now, if you go to podcast 61 or just look at the notes. The other idea that goes hand in hand with this is regression to the mean. People always talk about Sports Illustrated as the Sports Illustrated curse. If you’re on the cover as a great baseball player, football player, if you’re on the cover of Sports Illustrated, oh my God, this guy’s the best boxer we’ve ever seen. 12 to 18 months later, your performance is gonna fall. It’s almost guaranteed. They call it the curse or something like this. If you are an amazing stock picker, and oh my god, this is the best stock picker in New York at a hedge fund in 2020, almost for sure that person’s performance is going to decline because when they make the cover of the magazine, you’re looking at an outlier to the mean. You’re looking at an outlier to average performance and over time, most things will revert to the mean. They will regress to the mean. So when you get on the cover of Sports Illustrated, you’re seeing that sort of extreme moment when someone has hit the ball over the fence a ridiculous amount of times, the performance is gonna come back to the average base rate. Almost, usually. So you look at sort of what is the average level of performance for this skill, what its activity, and what is the rate of regression to that average. for this particular and sometimes it can be fast like stock performance is pretty fast other things it cannot so that’s kind of the idea you want to look and you can see books of these things you know you can you can do them yourself and you can find books and it tees up one last idea which is the idea of skill versus luck You wanna ask yourself this activity, is it about skill or is it about luck and what is the relationship there? If it is a game of luck or skill is not a big component, and I would say supermarkets, there’s not a lot of outstanding skill in supermarkets. So if you’re seeing outlier performance in a supermarket, it is more likely that, look, this is just some luck. Something happened, this company did pretty well, but over five years, 10 years, it is very hard to be dramatically more skillful in the management of a supermarket than someone else. So outlier performance is probably related to luck. If you think that’s the case, then it’s gonna regress to the mean much, much faster. Luck-based performance that’s amazing, regresses fast. If it’s a skill-based game, Like, look, this dude has been investing successfully for five years. Okay, you can have outlier performance as an investor that is based on skill, and it can actually stay as an outlier for a long time. You know, you kind of need to think about baseball performance, yes, maybe. Boxing, you can be more skillful as a boxer, but you know, most boxers. you’re in your prime for a couple years and then, you know, the new kids much faster than you and knocks you in the jaw. So yeah, you can have skill there, but it fades pretty quick. So you need to kind of assess these things. Buffett is a outlier, a skill-based outlier for 50 years. But there’s a lot of investors who do real well for two to three years. And then you look five years later and they’re back in the middle of the pack because it was just random. Anyway, so that’s kind of the other idea. Those are the three ideas. And I’ve given you some common metrics for base rates. Look at the show notes. So it’s not surprising that someone like Buffett would invest in a retailer. He doesn’t typically invest in supermarkets. I mean, they’ve said in the past, like him or Charlie, there’s only a couple business models they like in retail. One of them is clearly Costco. Charlie Munger loves Costco, and Walmart and a couple others. So it is kind of unusual for him to get into supermarkets. What is not unusual, is that he’s looking at a sector with very clear base rates, where you can really predict this in a way that you couldn’t predict other businesses. I mean, entertainment, hit TV shows, hit music, very hard to predict. Now, that brings us to the point, which is, why is it so hard to do the external view in digital? Because we don’t have a reference class. We almost, you know, so much of digital is always new. It’s a new digital tool. It’s a new digital business model. That makes… going from, hey, I’m studying the heck out of this company to, hey, I’m also looking at sort of a reference class to make it more predictable for me. We often don’t have a reference class. That makes it difficult. I think you kind of, if you’ve been listening to me for a while, you know I like certain business models. I like marketplaces for products, Taobao, Shopee. I like those business models. Why? Because I understand them. I think they’re powerful. I can understand where the competitive strength is coming from. And there’s a pretty good reference class for those businesses. I’m not looking at one company we’ve never seen before, like a, I don’t know, think up one like Quaisho or TikTok, which was a new thing. No, I can find a lot of these companies. I can find them in Ozone in Russia. I can find them in Mercado Libre in Argentina and Brazil. I can find them in Shopee and Lazada and Saudia. I can build a reference class for this business model and then start to complement what I think is a fairly… I’ll pat myself on the back. I think I have a better than most people understanding of how these businesses work, but I can also complement that and correct that with a external view. And that’s important because I don’t trust myself that much. So I want that. So I can get an external view. I like search engines. because I can look at, you know, there’s not a ton of search engines, but they’ve been around for 20 years. We know this model. I like Marketplace for Services, Ctrip. Even Didi and Uber and Airbnb definitely is really a pretty compelling business model. Booking.com, Agoda, Expedia. There’s enough of these, you know, Upwork, Fiverr. There’s enough of these Marketplaces for Services that I can start to build a reference class. And that’s really what I’m looking for. I get nervous when I don’t have a reference class and that’s not uncommon. Arm holding in the UK, you know, the SoftBank bought them tremendous competitive advantages. I have a heart, you know, they do sort of the IP library for making semiconductors and things. You know, it’s very hard to find any reference company, let alone a base rate for them. They’re pretty unique. Operating systems, I like operating systems. I can understand Microsoft. I can understand iOS. I can understand Android. I’ve been going through a company recently, Red Hat, which is an open source operating system for enterprises. Those of you who are subscribers, I’ll be sending you quite a bit on this company. It’s been since there’s been an acquisition, but there’s a lot of good lessons on how to think about operating systems. which are a type of platform business model that I have put under innovation platforms. It’s one of my five, so I like to drill down into the five. Okay, so that’s kind of why I sort of check a lot of this thinking when I’m looking at these companies. Okay, I like the company, I understand it, I understand its competitive strengths. Does it have, can I get an external view going? Can I build a reference class? Can I start to look at some base rates to check my thinking? And sometimes I can and sometimes I can’t. And if I can’t, I start to get a little nervous. For those of you who bought my book, you’ll notice in the first chapter, I sort of tee up the approach. And in the first chapter, what I put in there is basically an external view of the economic profits of various companies and where they lie that was done by McKinsey. They call it the power curve. I’ll put a copy of it in the show notes for this podcast. But basically they just went sector by sector, company by company and did a massive analysis, I think, that they built a book on called Beyond the Hockey Stick. And they said, look, this is the economic profits of companies. And most companies make very little economic profit, a small number, the top quintile, they make really attractive profits and the bottom quintile lose. And it’s also difficult to move from the middle to the top. And it’s as likely that you’ll fall down. So, you know, it’s this idea, look, most companies don’t make economic profit. It’s a small number. And that, I really use that to tee up the whole approach for the book, which is why I start with competitive advantage first. Anyways, I’ll put a link to that below and I’ll put the power curve in the notes. But. That’s a good book to read. Beyond the Hockey Stick, very good McKinsey book. And they also did something which I’ll put in the show notes called The Harry Back, which one, that’s a really cool idea. A good title, it’s really sort of catchy. And they basically, because they would work with strategy meetings, board meetings for lots of companies, and they describe it as The Harry Back, where, I’m gonna describe it, but it’s in the link, it’s below if you wanna look at it. Basically, the companies would do their strategy and they would project forward growth. Next year we’re gonna grow, and then the year after we’re gonna grow, and then the year after they’re gonna grow. So the line would go up. But then when they get to the next year to actually do the strategy planning again, they’ll look like they haven’t moved up. So well, now we’ll make another projection. We’re gonna go up next year, we’re gonna go up next year, we’re gonna go up next year. So it’s like there’s two lines going up and then they do the next year, but they’re still in the same place. And there’s, and. The net result of this is it looks like a line with a bunch of hairs coming up because their performance didn’t really change. They stayed at their base rate, but they kept having these projections going up and they call it the hairy back. I’ll look at it in the show notes. It’s once you see it, it’ll stick in your mind forever. It’s a really good sort of way to think about business. And that’s companies fighting against the base rates and fighting against the external view. You know, everyone plans to grow and we plan to increase, but a year later, we’re pretty much where we were. Maybe we grew three to 5%. We kind of got average performance. The average dentist is still making $250,000 a year, despite all their big plans. It’s just the way it is. So that’s another way to think about it is the hairy back. I’ll put that in the show notes. And the power curve. Anything else I wanted to cover today? Why do investors make mistakes? This will be the last point. Why does the internal view, why is it so seductive to your typical analyst? Computers think in terms of big numbers and statistics and data and probabilities. That’s why that’s a very good approach to doing the external view is to do data analysis, just analytics. Our brains don’t do that very well. We are not good at… keeping the data for a thousand companies in our brain. So we sort of gravitate to the internal view because we’re good at that. We’re good at taking things apart, small things. And that’s a strength, but it also plays into some psychological weaknesses. I’ll give you a couple. The halo effect. These are just standard psych stuff. That when we see financial performance. Attractive financial performance, we tend to attribute it to actions and skill, not just to hey, that’s just what the whole market does. You know, the whole market behaves this way, so when this company went up, it’s easy to say, well, that management team was awesome. Nah, the whole market was just going up. We put a halo around certain people and actions and companies and management teams. Nah. Anchoring. If we grew by 8% last year and 8% the year before, when we project what the growth is gonna be next year, what do we come up with? 8%, 9%, 7%. We use last year’s numbers as an anchor to then project forward. That’s usually not good. Confirmation bias, we like to study why things will work. We like to look for things that reaffirm the opinion we already have. We tend to avoid things that don’t and we tend not to see it. You know this is really strong in politics and ideology. Like if you ever notice when you read the newspaper or where you read a news feed you will read the articles that confirm what you already tend to believe is true and if it says what you think is not true, what you think is true is not true, you will avoid it. It’ll actually make your blood pressure go up. Like your blood pressure literally goes up when you read the news and you see something that sort of is against what you already believe. And then you’ll immediately click on this way. You know, politically, all the left watches certain news stations and all the right watches the other and they all that’s where they sit. I don’t know. Performance attribution errors. this idea that when things are going well and companies are doing successful moves and revenues going up, it’s actually very difficult, well, let’s say more difficult to understand where that is coming from. Look, was this a bunch of luck? Were you just in the right place at the right time and the market was going? Was this just about the market? Did you just have a hot product and people just tend to like it? Was it about management capability? I mean, when you see good performance, good momentum, it’s actually hard to figure out why that happens. It’s actually easier to figure out when things fall apart. It’s easier to take apart and figure out why. If people tend not to dig into that deep enough, management ability versus the market is the way it is versus just luck, just random behavior. You’re just doing well and you’re sinking the baskets this quarter. You’re out on the court and for this whole half of the game, you’re just sinking everything. Why? I don’t know. And then the next day it doesn’t happen. And last one to think about, uncertainty tends to be an afterthought. Now those of you who have been listening to me for a while, you know I’m big into uncertainty analysis. Like I do it all the time. I don’t want to know what the most common projection is. I want to know what are all the possible scenarios that can happen. And I want to know the ones with the highest level of certainty. I am much happier to know and be 98% certain of a scenario that can’t happen versus a base case where we’re 30%, 50% certain it can happen. I like to know that like I don’t know what’s going to go on with this company, but I know their revenue is not going to be above 150 million. I am almost entirely sure there’s no way this company can break 150 million. So I’m going to rule out everything above 150 million. I’m also gonna rule out under 100 million. I know there’s no way this company can go under 100 million. It’s just Coca-Cola, everybody drinks Coke. The number of human beings is not gonna decrease that much in a year. Three to five years from now, there’s no way it’s less than this. So I know it’s more than 100. I am confident it’s less than 150. That’s all I know. That is me approaching a scenario projection based on uncertainty first. And you know, those of you, if you go back and listen to my evaluation talks, that’s how I approach things. I like uncertainty. Uncertainty analysis as the primary thing, and then specific projections are second. So I think that’s it for today. Takeaways for you would be maybe take a look at Kroger, go through their 10K. If Berkshire’s buying this year, that might well be an opportunity. Maybe not, you know, make your own decision. I don’t know. I… I’m not sure why he’s buying, to tell you the truth. I’ve looked at the numbers and I can’t see why they’re doing it other than maybe just the valuation, which I haven’t run a valuation on that one. But anyways, take a look at it. It’s probably a good exercise and if nothing else, the way they lay out the accounting for inventory and stuff is really well thought out. I found that very helpful. Point number two, key concept for today would be external versus internal view. Very important. Other concept today, regression to the mean, which is a lot of base rates, things like that. And in the show notes, I’ve given you some details. I’ve also given you a graphic for the hockey stick, the hairy back, the power curve, and the beyond the hockey stick by McKinsey. Okay, I think that’s it for today. As for me, I had a pretty great week. I went down to Hua Hin for the weekend, which is… three, three and a half hours southwest of Bangkok. It’s pretty commonplace for people to drive down. It’s nice beach, which everyone knows about. But which I didn’t know about is directly to the west. You know, really right there is, you know, the largest national park in Thailand. You know, it goes right up basically from the beach, Hua Hin, you go west, then suddenly the mountains go right up and you’re basically on the border with Myanmar and the mountains are absolutely beautiful. Lakes, you know, it’s really spectacular. I think that is where the tigers start to show up. There’s a lot of interesting animals in Thailand and one of them on the list that’s dangerous is tigers, but they’re not really in Thailand per se. They’re on the border with Myanmar, up in the mountains is where they tend to be. I think that’s what I was thinking when I was up there. Anyways, I went down there because I’m playing with this idea of maybe having a farm, or maybe not the farm is the right word. I’m thinking more just a mountain camp. somewhere to go and sit under the stars and have a house and that’s kind of what I’m not gonna ever do any farming. Although I do love the idea of buying a water buffalo and naming after my father. So if I do do this, I’ll get Wayne the water buffalo, which I’ve priced out. Actually, it’s only a couple thousand dollars to get a water buffalo. Anyways, I went down there to kind of just look around and see how I felt about it and one of the subscribers, Tau, you know, sort of sent me a note and said, you know, come down and her and her family are from that region, Pechaburi. And man, I had a wonderful time. Tao and her father took me out the whole day. It was, you know, sort of overwhelming, like all over the area, up into the mountains, up into the, you know, to the lake, lunch by the lake, up in the mountains, which was absolutely beautiful. Then down to Hua Hin. sort of in your nightfall into the Sikkim market, for those of you who know that, unbelievably nice market, which I didn’t really know about, sit there and it was just fantastic. And I really appreciate it. So thank you to Tao and Father. That really meant a lot to me, I appreciate it. And it looks like, and for those of you who aren’t familiar, those of you in Bangkok, I think you know her. She has a group called Vietnam Value Investors. very successful and this is for Thai value investors mostly who are looking at Vietnam. They’ve been doing this for a while. Fantastic. That’s just a really great approach. I mean, it’s just a good strategy. It’s a good thing to be doing. You know, if you’re in Thailand and you’re a value investor, I would say look at China, which is kind of my thing, but look at Vietnam. That’s a really interesting market and I haven’t really touched on that much. Anyways. So thank you to Tao, I really appreciate it. And it looks like I’ll see you in a week or two, because I’m going back down and we’ll maybe go to some other areas. But the net result of that sort of initial exploratory trip was this may turn out to be one of the best ideas I’ve ever had. It went from a funny, everything sounds good in your head, right? Or at least in mine. But then you go try it out and you’re like, ah, this doesn’t work. Like last year I thought maybe I’ll do a little home and pookette. and I flew down there a couple of times and I’m like, yeah, I’m not gonna do this. I don’t wanna do it. I’ll fly down when I wanna go to the beach. It’s $30, it’s nothing. This one turned out to be, cause you can basically have a really wonderful place in the mountains or just in the hilly areas, green, lush rivers. It’s absolutely beautiful. And then 30 minutes later, you can be, you know, at the Intercontinental Bar. on the beach in Hua Hin having a drink. I mean, you can just zip down the mountain and be sitting on one of the nicest beaches, really, you know, in Southeast Asia, you know, and have a drink and then just putter back up to your little mountain place. Really easy. Anyways, I’m mulling it over, but it turned out to be a pretty great experience. So thank you, I really do appreciate it, Tao, and your father. Anyways, that’s it for me. I’m gonna be around here for another. at least three weeks and then I’ll probably bug out of Thailand. But yeah, next week back to Hua Hin. So that’s it. I hope this is helpful. If I can ever be of help, don’t hesitate to reach out. Everything’s in the show notes and I will talk to you next week. OK, bye bye.