Bottom line: Alwaleed’s forty years of success as a master deal-maker and negotiator have come to a head as he now negotiates for his empire and his freedom.

For 8-9 years, I worked for Prince Alwaleed in Riyadh, working on everything from his IPO and his hospital to his university (never built) and his one mile(?) skyscraper (under construction). I have spent years sitting down the hall from him, both in his Kingdom Centre skyscraper and in his previous office on Takhasussi road. And I have studied and taught about his investment strategies for over 17 years.

And since the Royal arrests in Saudi Arabia two months ago, I have been getting call after call. My reply has been “I don’t know what’s going on.”

Like most, I have struggled to get accurate information. From the press reports, the motives of the Saudi government appear to be a mix of fighting corruption, getting cash and consolidating power. And the latest rumors are that Prince Alwaleed has been offered a deal for his freedom that requires him to hand over $6B and maybe control of his company.

I don’t know how much of this is true. But assuming some type of negotiation is happening, I am fairly confident in making some predictions about that. I lay out four predictions in Part 2. But first some background on Alwaleed and his approach to deals.

1979-1985: Alwaleed’s first deals

In 1979, Alwaleed, just returned from college in California, opened his investment business in Saudi Arabia. Originally called Kingdom Establishment, it began as a simple office in a prefabricated structure in downtown Riyadh. You can see a model of it in the lobby of Kingdom Holding Company today (picture below).

The first Kingdom offices (1979-1983)

The driven young Prince, with no clear path in government, took the path of the merchant prince. Sitting in his small office and borrowing money from his father and later Citibank, he began knocking on doors and striking deals. It was not something that Princes normally did.

But his timing was spectacularly fortuitous. Saudi Arabia was a few years into its first oil boom and undergoing an unprecedented development effort.

- Approximately $100-150B in oil revenue was flowing annually into a country of only 9M people.

- A massive government development effort introduced paved roads, air conditioning, supermarkets, cars, modern hospitals, telephones, airports, industry and just about everything else to Saudi Arabia for the first time.

- Saudi life underwent sweeping changes. Life expectancy and literacy rates soared. Mostly mud structures were replaced with concrete and steel. Camels were replaced by cars. And a nation of traders and Bedouins moved to the cities and became business people and bureaucrats.

The camel market in Riyadh circa 2001.

Awaleed initially struggled in this period and he reportedly almost went broke a few times. But he eventually began to find modest success. He scored a contract for the construction of a military barracks. He profited from both a State-dominated contracting system and from foreign companies eager to get involved in Saudi’s development projects. And he aggressively moved his increasing cash into real estate (always a good idea in an oil country). His reputation as a particularly canny businessman began to emerge.

By the mid-1980’s, the Saudi government had spent over $500B on development initiatives, the country was transformed and Alwaleed had found success.

1985-2000: Alwaleed emerges as Saudi’s most creative investor.

Oil prices crashed in 1986 and many Saudi private enterprises failed. Additionally, a still largely primitive banking sector was revealed to have created extensive bad debts during the boom years.

It was during these post-boom years that Alwaleed began to show two traits that would eventually make him famous: hyper-focus and a creative approach to investing.

- Hyper-focus. Despite his increasing wealth, Alwaleed kept his office and his staff very small, typically just 2-3 business advisors and a financial controller. Having such a small staff ensured he could focus on only a small number of projects. This limitation, plus some really good instincts, is part of why he always seems to be where the best opportunity is at any given time. He didn’t just do deals. He did the best deals. He has a hyper-focus in his investing. And you can see this in his frequent switching of strategies and targets through the years.

- Creative strategies. In my experience, Alwaleed virtually always sees something in a deal or opportunity that others don’t see. He comes at this things from a different angle. I think this mostly follows from how his brain works and his experience. Looking at situations differently can be a big advantage in investing.

So how did Alwaleed respond to the post-boom bust in Saudi Arabia? He moved to where the best opportunity now was and did something nobody expected.

In 1988, Alwaleed orchestrated the first hostile take-over of a Saudi Arabian bank. And he didn’t target one of the good banks. He targeted United Saudi Commercial Bank, then the worst of the country’s banks. He worked with its investors and the government and took control of the troubled enterprise. And he took the reins as CEO and personally cleaned up the debts, slashed costs and returned the company to profitability. He became a turn-around expert. Note: He was also buying distressed real estate in this post-boom period.

As the crisis receded, Alwaleed was a major player in the Middle East. He was the owner of one of the nine major Saudi Arabian banks and had extensive Riyadh real estate. And this is a good example of his hyper-focus. If there are two things you want to own in an oil country long-term, it’s banks and real estate.

Over the next decade, Alwaleed’s increasingly creative moves continued. And he always seemed to be in the most lucrative opportunities.

- In 1991, he made his big move into the West, buying 10% of Citibank for $590M, while still at the of age 33. Within 5 years, his stake was worth $8-10 billion.

- He became a Western bargain hunter, acquiring “down but not out” companies such as the Fairmont hotels and Eurodisney. These deals were typically done as PIPEs or as stakes in private companies with significant real estate or other fixed assets. Both of these approach limit the risks of cross-border investing.

- In Saudi Arabia, he expanded from a real estate trader to a developer of large scale projects. He acted as master developer for Kingdom Center downtown. As well as for multiple projects in the north of Riyadh.

- During the dot com boom, he went to Silicon Valley and began investing directly. He famously invested in Apple shortly before Steve Jobs returned.

- In Africa, he launched one of the first African private equity funds, about a decade before KKR, Carlyle and the private equity world followed suit.

Alwaleed had evolved from a Saudi trader and contractor to a turn-around investor to a Western bargain hunter to a global real estate / hotel developer to a cross-border private equity specialist. He seemed to move from strategy to strategy, from industry to industry and from geography to geography. There is actually a common approach in all of this (which I call Value Point) but you will have to read my upcoming book for that.

As 2000 approached and the business world went increasingly global, Alwaleed’s creative and opportunistic approach turned out to be a particularly good skill set to have. And he did all of this while still operating from a small office in Riyadh with only 2-3 business staff,

2000-2010: Alwaleed becomes the world’s first private global investor.

In 2000, I met Alwaleed for the first time. The project was a distressed hospital and I was coming in as a US healthcare guy. I clearly remember walking into his headquarters on Takhassusi Road for the first time. His personal office was mostly decorated in black, and with little light. It was noticeably chilly and it felt like entering a cave.

As my team entered his office, Alwaleed was sitting behind a big desk reading (as always) and briefly glanced up before going back to his report. We took the chairs in front of the desk and waited.

Eventually he turned his attention to us and it was right to business. And it was rapid-fire. What was going on with the hospital? Why was it losing money? Was the strategy wrong? I quickly learned that working for Alwaleed is rarely about talking or giving him long explanations. It is mostly about sitting in front of his desk, answering his rapid-fire questions and feeding him data. It can be mentally tiring. But his staff do bring you fantastic Saudi coffee to keep you going.

After several hours of this, we exited exhausted and another group with another project entered as we left. Alwaleed continued with the next group in the same manner and at the same pace. His days are basically an endless series of these types of rapid, intense meetings. You take a seat in front of his desk. You speak fast, deliver the information and give him direct answers. And there is always another group waiting on deck in the lobby.

We headed across to the second floor office of Talal Almaiman to relax and discuss. We had more coffee and then planned our next steps for the project. Little did I know that I would end up doing this same Alwaleed-to-Talal’s office walk hundreds of times over the following years. Talal, a fantastic guy and a particularly clever thinker, is now the CEO of Kingdom Holding in Alwaleed’s absence. My favorite quote by him was his explanation for how he had worked at KHC for so long (most people get burned out after several years). Paraphrasing, he said “before every meeting with HRH, I prepare for what question he might ask. I prepare information that I think he might ask for. And every meeting I am wrong. And yet he never seems to fire me.”

The old KHC office on Takhassusi Road

This was in 2000 and Alwaleed was at the end of his second decade in business. He was on the Forbes list as the world’s 4th wealthiest person. And his holdings had grown to include hotels, banks, supermarkets, hospitals, media properties, tech companies, real estate, a school, and many other properties. He had basically assembled a private empire that circled the global. And if you look at any photos of him at work, you can always see a big display of these company logos behind him. Note: there are also smaller versions of this display on his boat and at his desert camp. This, of course, raises a question “if you sell a company, do you take the logo off the display?” To which the answer is “no. It is part of KHC history”.

I spent my first six months in Riyadh commuting between the hospital in the morning and Alwaleed’s office in the afternoon. The hospital was losing money. I was terminating people left and right, restructuring the operations and trying to keep the suppliers delivering. We eventually restructured the business, reset its capital and merged it with a large outpatient facility downtown (hi Dr. Fayez). Today, Kingdom Hospital is arguably the best hospital in Riyadh.

After the hospital, the Alwaleed projects just kept coming. I jumped into a troubled internet investment in Dubai and Jordan. Then a university project. Then health insurance. Then a shopping mall, a Saks Fifth Avenue store and some huge real estate projects (collectively about the same size as Manhattan). And so on. Alwaleed has fascinating projects around the world and he’s just a really difficult person to say no to. Also during this period, Alwaleed moved his company to its current office at the top of Kingdom Center.

Kingdom Centre. Alwaleed’s office is on the 66th floor, right below the gap. Although it’s not really 66 floors.

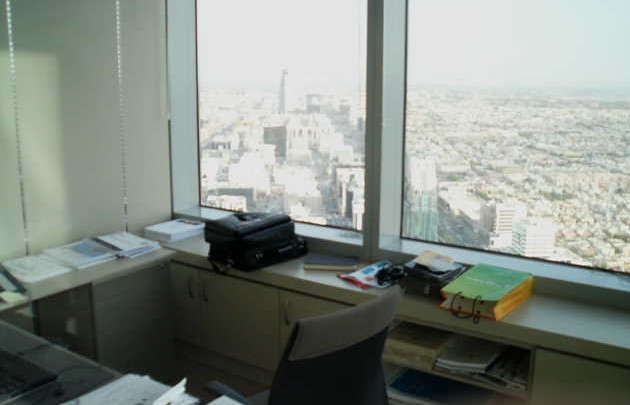

My desk, which had fantastic views of Riyadh’s sandstorms.

2017: Alwaleed’s spectacular fall

Alwaleed’s most famous quote is “I do something spectacularly or I don’t do it at all”. And certainly his rise to billionaire status at around age 31 was spectacular. His acquisition of Citibank at age 33 was particularly spectacular. His possibly one mile high skyscraper under construction in Jeddah is spectacular. And so on.

And you have to give him credit, his fall has also been spectacular.

Alwaleed did not announce his retirement and then fade from public life in Cannes or Paris. He did not suffer a medical issue and slowly hand off his responsibilities to others. His fall came suddenly late at night with armed men. His fall has been sudden, dramatic and, yes, spectacular.

And like his rise, his fall is inexorably intertwined with the history of Saudi Arabia. In this case, it has become symbolic of the end of one Saudi Arabia and the beginning of another. Whether his fall is permanent or temporary remains to be seen.

Today, forty years after his start in a prefabricated office, Alwaleed is negotiating from a different small room in Riyadh. This time he is under guard at the Al Ha-ir prison(?) in southern Riyadh. And the master deal maker and negotiator is now negotiating with the government to retain his empire and to regain his freedom. It is the negotiation of Alwaleed’s life. One wonders if he can see his skyscraper from his room.

That’s it for Part 1. In Part 2, I will lay out 4 predictions on what I think will happen in this negotiation.

Thanks for reading, Jeff

The cleaning crew at Kingdom Centre

A trip to the “edge of the world”, deep in the Saudi desert

———

I am a Professor of Investment at Peking University Guanghua School of Management in Beijing. I am also an investor, best-selling author and former executive to Prince Alwaleed.

Top photo by Photo by Hala AlGhanim on Unsplash.