This week’s podcast is about separating networks (an asset) from platforms (a business model) from network effects (a phenomenon). And the three standard types of network effects.

You can listen to this podcast here or at iTunes, Google Podcasts and Himalaya.

I put networks into 3 types:

- Physical Networks

- Protocol Networks

- People Networks

I put network effects into 3 types:

- Direct (One-Sided) Network Effects

- Indirect (Two-Sided) Network Effects

- Standardization and Interoperability Network Effects

Questions for network effects:

- Local vs. regional vs. international network effects?

- Fast vs. slow network effects?

- Degree vs. value of connections?

- Minimum viable scale vs. asymptotic scale? What is congestion / saturation / degradation scale?

- Linear vs. exponential growth at different scales?

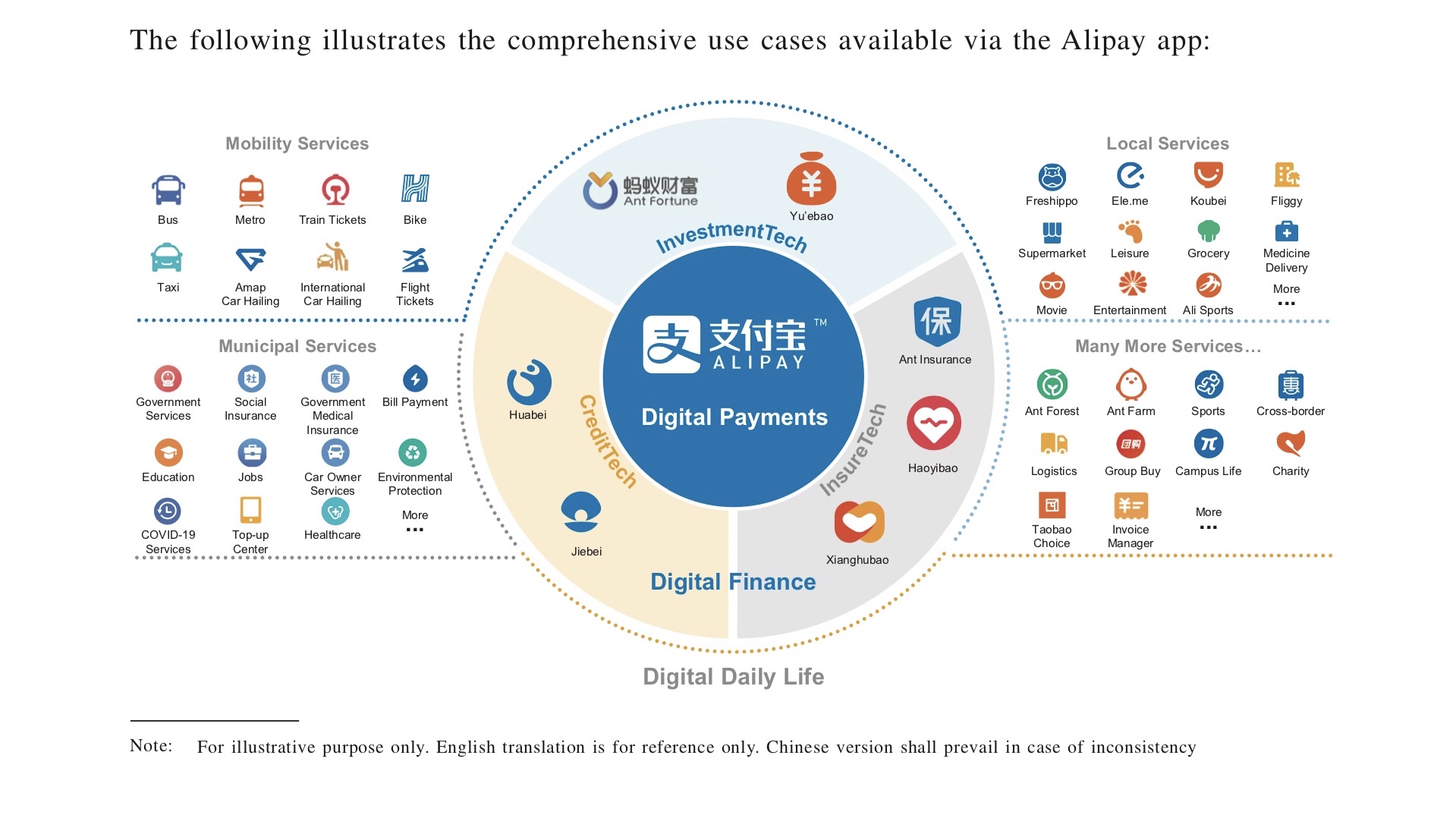

Here is Ant Financial’s self-description from its IPO filing:

——–

Related articles:

- Ant Financial Is 3 Platform Business Models Combined. (Jeff’s Asia Tech Class – Daily Lesson / Update)

- Ant Financial’s Big Money is in Asset-Light Credit Tech (Jeff’s Asia Tech Class – Daily Lesson / Update)

From the Concept Library, concepts for this article are:

- 3 Networks vs. 5 Platforms vs. 3 Network Effects

- Network Effects: Direct and Indirect

- Network Effects: Standardization and Interoperability

From the Company Library, companies for this article are:

- Ant Financial

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

————-

I write, speak and consult about how to win (and not lose) in digital strategy and transformation.

I am the founder of TechMoat Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that helps retailers, brands, and technology companies exploit digital change to grow faster, innovate better and build digital moats. Get in touch here.

My book series Moats and Marathons is one-of-a-kind framework for building and measuring competitive advantages in digital businesses.

This content (articles, podcasts, website info) is not investment, legal or tax advice. The information and opinions from me and any guests may be incorrect. The numbers and information may be wrong. The views expressed may no longer be relevant or accurate. This is not investment advice. Investing is risky. Do your own research.

—–Transcription Below

:

Welcome, welcome, everybody. My name is Jeff Townsend, and this is Tech Strategy. And the topic for today, AMP Financial and the Three Types of Network Effects. So this is going to be a little bit like last week, which is a bit of theory, just sort of baseline, basic theory that I’ve sort of mentioned from time to time, but I haven’t really laid out. So I’m going to try and lay out just network effects in a more systematic way. And then 50% talking about a company that’s benefiting from this and sort of how to think about that. And I think Ant Financial is a pretty good example of this. Now my apologies, I’m a little bit late again this week. It’s Tuesday so I’m a bit behind, which has happened a couple times. I’ve basically been buried in Mexico City writing a book, which is great and I’m basically done. But yeah, it’s been kind of a bear. So I put this off for a little bit. Now I have three concepts for today’s talk. I generally like to sort of cover two, maybe three concepts each podcast. And these are sort of base core concepts for digital strategy. And there’s not a huge number of them. There’s probably 30 to 40 really important ones. And I try and cover a couple every time. And maybe for some of you, you’re very familiar with this. But for others, it’s maybe you’re still learning some of this stuff. That’s totally fine either way. So anyways, the three for today, which are always listed in the show notes, and you can always just go to the concept library on my web page and you’ll see them all listed there, and you can click on there and just see articles that cover them. But the three for today, first one is network versus platform. What’s the difference between a network and a platform? And then the second one, which is network effects, which sits on both of those, and there’s two here. There’s… Direct and indirect network effects, so that’s kind of one concept. And then there’s what I call standardization and interconnection network effects, which is another. So three ideas. Networks versus platforms, direct and indirect network effects, standardization and interconnection network effects. It’s in the show notes, so you can find it there. Other stuff for subscribers coming up, which I’ve mentioned before, but I haven’t gotten to it, is I want to talk about Truck Alliance, which is filing for an IPO. And then of course the Didi IPO and the numbers have hit. You can go on the SEC website and pull their numbers for the first time, which is really fascinating. Although they didn’t file under the name Didi, they filed under the name Xiaoju Kuai Zhi, which is kind of unusual. I guess it’s because that’s the technical name of the Caymans Island Company or something like that. I just think it’s kind of funny that there’s no real English equivalent to that. word. Either of the words. Those phrases, xiao and kuai zhi, there’s no real English equivalent to those sounds. So we’re going to get to hear CNBC and other people. They’ll probably get xiao right because Xiaomi has been around. They still mispronounce hua hui. They still say hua hui a lot, but we’ll probably get them hear them mispronounce kuai zhi a lot. So anyways, that’ll be fun. So that’s coming up. Okay, so I’m gonna cover those shortly for the subscribers. For those of you who aren’t subscribers, feel free to sign up over at jefftausen.com. There’s a free 30 day trial, see what you think. Join the group. Okay, oh, I gotta do my disclaimer. Last thing, standard disclaimer. Nothing in this podcast or in my writing or on the website is investment advice. The numbers and information for me and any guess may be incorrect. The views and opinions expressed by me may be incorrect or no longer relevant or accurate. Overall investing is risky. This is not investment advice. Do your own research And with that let’s get into the content Okay. Now I’ve written about Ant before quite a bit and My main take this was when Ant was gonna go public and we got to see their numbers which were really interesting by the way And my take was that Ant was basically three different platform business models stuck together Okay But then I’ve just kind of said, look, today’s talk is about three different types of network effects. OK, so we can have multiple types of platform business models. And I’ve basically laid out five in the past. OK, five different types of platform business models, three different types of network effects. It also turns out you can have multiple types of networks. So you’ve got kind of these three ideas that I think are easy to get confused. Networks. versus platform business models versus network effects. And I’ve laid out multiple types of each, but that’s just my take. Other people will cut this down a little differently. I think five types of platform business models, three types of network effects, and then generally three to four types of networks is what I see most of the time. There are exceptions and you could slice this different ways, but that’s kind of how I break it down. But it’s always evolving because people invent new stuff, right? But these three ideas are kind of easy to get confused. So I’m going to sort of tell you how I view it. And then we’ll go into Ant, and that’ll be kind of the example. So let me start with platform business models. Now, a platform business model versus a linear business model. And most business models are linear. It’s like a pipeline. People call them pipelines. They call them vertically integrated industries or businesses. I mean, just think of a factory floor. The goods come in one end. at the dock, it goes down the conveyor belt, you make the car at the other end of the factory floor, out comes the car, you sell it to the customer. It’s a linear process of adding value, generally through a tightly coordinated effort of labor, assets, technologies. That’s kind of what happens in every step of the process. And so at the end, the car is worth more than the goods that went in the other end to make it. That value add is the purpose of the business. a linear business model. Now a platform is a business model that has a primary purpose of creating interactions between different user groups, merchants, consumers, people looking for a ride, people giving rides, people looking to date, people looking to send money, people who want to receive money. Your primary purpose is to serve two different user groups and help them interact, and that’s how you add value. And the more people you connect and the more people you enable to interact, the more value you add. Now, I’ve covered that before. But I’m just teeing up a question here. OK, if a platform is a type of business model, what are the assets you use to create a platform? Now, the assets I use to create a factory, we know what those are. It’s the factory, it’s people, maybe it’s some technology. Those are the assets. I put those together. That’s not the business, that’s just the asset base. The business model, the linear pipeline is what creates value with those assets. Okay, the network is the asset for the platform business model because a platform business model is a network-based business model. We are helping things connect, but we already need to have an asset base of things that are connected, and we call that a network. So, An example would be a railroad. A railroad is a physical network. It’s a series of assets. We lay the track, we have the rolling stock, we have train stations, we have depots, we have people who drive the trains. Those are all the assets, but it’s not the business. The business is, hey, we’ve got a shipping company. That’s our business model using that asset base. In this case, the business model is a network-based business model that uses this network. So platform business model, that’s your business model, your business, the network, that’s your assets. A good example of this, it’s a Warren Buffett example, like look, you can buy assets, like if you go to business school, you’re buying an asset, you’re buying a degree. That doesn’t necessarily, that’s what you spent. It doesn’t mean that’s what it’s worth. What it’s worth is what you go on in your career to do with that particular asset. You become a banker or whatever. So one’s the asset, you can kind of buy those often. The other’s the business model. Now the railroad example is kind of easy to understand because you can visualize it. You can see the trains, you can see the railroad, and the company, the railroad, that is the business, they also own the network. So it’s kind of one thing. The company running the platform business model, the shipping or moving people or something. They also own the asset base, which is these physical assets, and we would call that a physical network. That’s kind of easy to understand. But there’s other types of networks. We could have a protocol network. Now, protocol network could be like a TCP or ICP or ethernet cards, things that enable connection between compatible communication devices. So that would be. We’ve got a bunch of PCs. When we add these ethernet cables, all the PCs become a network. So it’s a protocol network based on the standard and usually some technology. And when networks started to really emerge in the tech age, which was like the 70s, that’s what people talked about. They talked about protocol networks. In the 20s and 30s, everyone talked about physical networks. AT&T used to talk about physical networks. We lay the cables, we put up the telephone poles. physical network, but you get to the 70s and everyone talks about protocol networks, which are a little harder to visualize. And this is where you started to get things like Reed’s Law and Metcalfe’s Law and these rules about how the number of connections goes up at the square of the number of nodes and whatever, which I don’t agree with most of those. If you’re talking about protocol networks, fine, but people still cite them and I don’t think they’re really relevant to anything. But when you build a network as an asset… You have nodes, and then you have linkages between the nodes, and that makes up the asset. And you could think about, well, how many connections are there per node? How do the number of connections go up every time I add a node? Are some connections more valuable than others? Which they would call clustering, things like that. Anyways, not that important. But you can kind of see, OK, that was an asset base, but there wasn’t necessarily a business model built on a protocol network. Then we get to. people-based networks, which have always been around. You know your friends, you know your family, you know the people in your town. We’ve always had social networks, people networks. Well, as soon as you put a smartphone in everybody’s hand, you could say that the smartphones are the network. It’s a protocol network that connects compatible devices. That’s everybody’s smartphone connects with everyone else’s smartphones. But is that really the network that matters for Facebook? No. I mean, the network that matters for Facebook is a social network. It’s a people network that just happens to sit on the protocol network. So I mean, when you’re talking railroads, it’s kind of easy. But once you start to get into the digital age, you kind of realize there’s network on top of network on top of network. And it’s like the protocol networks enabled the smartphones, and the smartphones enabled. the operating systems and the operating systems enable the people networks and then you can have, and you can cut this a lot of ways, which people try and do. They try to say, look, there’s 20 different types of networks. There’s physical networks, there’s a radio networks, there’s protocol networks, there’s personal social networks, which would be a type of people network. There’s professional networks, social networks, which will be different. There’s utility people networks. There’s market networks. People try and slice all these things, although I generally think, look, if we’re talking about assets, I think there’s four or five types of networks total, physical ones, protocol ones, people ones, and then maybe one or two others. But beyond that, I start to think, okay, let’s just talk about platform business models, because that’s really what we’re sort of blurring into. But you will see people try and map out 10 or 15 or 20 different types of networks. I don’t really find that helpful. I think most of the stuff we’re talking about on a daily basis is various different types of platform business models that happen to run on either physical networks or people networks. That’s most of what we’re talking about. And I don’t really break it down much beyond that. But this is sort of concept one for today. this idea of the platform business model versus the network, which is the business model versus the assets. It’s the fact that we’re making cars versus the fact that we have a factory. Okay, and that brings us to the other topic, which is a network effect. What’s the difference between a network effect, a platform business model, and a type of network? So, there’s sort of three things that are blurring together here often. Now, network effects are… You could consider them a special subtype of a feedback loop. People often call them network externalities, demand side economies of scale. But really, I just say network effects. It’s the same thing. But it’s a phenomenon. A network is a series of assets, nodes, and linkages. A platform is a type of network-based business model. A network effect is a phenomenon that can exist within this. It’s just a phenomenon. It’s a quirky happening. It’s a feedback loop. It’s actually a special subtype of a feedback loop. And what it is as a phenomenon, it’s a situation where the more users and or usage of a product or service, the better it becomes. The value and or the utility of this service increases with its users and or usage. That’s actually kind of specific language. I kind of thought about that for a long time. I’ll say it again. It’s a phenomenon where the value and or the utility of a product or service increases with its number of users and or the usage. Standard example, if you join Zoom, my Zoom service, just got better because now I can call more people. If you join WeChat, my WeChat just got better because I can call more people. If you go to KFC and buy chicken, my chicken dinner doesn’t taste any better, doesn’t increase the value and or utility of the product or service in that case, doesn’t increase with more users and or usage. OK. Now. That’s kind of the primary thing, but one of the reasons network effects get complicated is because there’s actually multiple things happening. The network effect actually causes a couple different things to happen, and depending who you’re talking to, people are talking about one of them or all of them. Venture capitalists love network effects because it’s a powerful mechanism of early stage growth. You know, they call it, the phrasal here sometimes is a bandwagon effect. when a new service like WhatsApp jumps in, more people use it, it becomes more valuable with more users and more usage and or more usage, the service gets better and more people join in because they kind of hear about it, they don’t want to be left out, competing services, the people jump from that one to this one because it’s clearly a better service. So you get this early stage acceleration and growth and kind of it’s the phrase you hear is bandwagon. So that’s kind of a thing or sometimes they say look you get this early stage growth that’s kind of one phenomena one aspect of a network effect. The other one you’ll hear is people talking about a tipping point or it when the market tips and that’s when one company gets enough volume people call it critical mass sometimes when one of these network effects gets enough volume. the whole market tends to collapse to them very quickly. And you have to reach a certain point where you’re viable, your value is significantly more than your competitors, the value created starts to exceed the cost. At a certain point, they call it the tipping or whatever. So you hear about, there’s a bandwagon effect, there’s a tipping effect, or I don’t think they say tipping point, but there’s sort of a when the market tips. Those are different things. What I’m talking about is basically a demand side economy of scale, a competitive dynamic, which is when my communications network, WeChat, has more users and or usage than another communication device, let’s say line, that difference makes my service better and that is a competitive strength. and defensibility, it’s a competitive advantage. And a demand side economies of scale, you can see that on the supply side as well. If I have a bigger factory than someone and there’s a fixed cost differential, I’m sorry, if there’s a volume differential with the same fixed cost, I’m gonna have a lower per unit cost than my competitor. I have a supply side economy of scale advantage. So what I’m talking about when I talk about network effects is this third idea, which is when is a network effect a competitive advantage? As opposed to these other ideas of, oh, it’s a bandwagon effect, it’s a growth accelerant, it’s a tipping point. There’s a lot going on with network effects, but I’m mostly talking about competitive dynamics because that’s my thing. And just like supply-side economies of scale, this is a competitive advantage that only persists as long as I keep a scale differential between me and a competitor. So it’s a very specific competitive advantage between company A and company B. Company A has twice the volume of company B. Let’s say they’re a factory. Same fixed cost, but company A has more volume. Therefore, they have a lower per unit cost. Then B. Same thing with demand side economies of scales, network effects. Because company A has greater volume than company B, it is a superior product. You need a persistent scale advantage or scale differential to have a sustainable competitive advantage. Okay, a couple qualifiers within that. I know that was kind of a little bit of theory. Couple caveats, qualifications. Networks and platform business models are different things. Networkers are assets. Platform business models are business models. The assets that make up a network are generally the nodes and the linkages. and they can be tangible or intangible assets. And often they’re both. Social networks are almost entirely made of intangible assets. Railroads are made of tangible assets. What’s interesting about e-commerce and telephones actually is the network is a mix of tangible and intangible assets. Yes, when you have a telephone network, you have to lay all these cables and telephone poles and all that, that’s physical assets, intangible assets. tangible assets, but it’s also carrying digital information down the lines, although it wasn’t digital for a long time, it was analog, but it’s information that’s an intangible. E-commerce, yes we have all the warehouses, that is part of the physical tangible assets, but we also have the mobile app on your phone where you buy stuff that’s intangible mostly. So they can kind of be a mix. Utilize networks. If they don’t, how can you do an interaction-based business model without a network that lets you do interactions? However, not all platform business models have network effects. Newspapers. A classic old newspaper is a platform business model. You have readers. That’s a user group. And you have advertisers. That’s a user group. But nobody thinks that if more people read a newspaper, it’s not better for other readers. And if more people read a newspaper, let’s say if more advertisers are active on a newspaper, that’s not better for readers. Now, you could argue that the more people that read a newspaper, the better it is for advertisers. But there’s not really much of a network effect going on with your classic daily newspaper. Platform business models have different types and strengths. Same thing with network effects. There’s multiple types, but there’s also different sort of styles and strengths. Some are really strong, some are pretty weak. And this one’s important. A network effect is a perceived increase in value or utility to a user. So if I’m a consumer on Lazada, For me, the network effect is as more merchants join Lazada, it gets better for me. But that’s the consumer side view. You have to also look at the merchant side view. If more consumers go on Lazada, does it make it different, more valuable, with more utility for the merchants? And when I talk about strengths and weaknesses of network effects, they can be different on different sides of the network effect. So it may be very strong for one user group, but not for the other. So you’ve got to look at it from the perspective of each user group. Last point. Well, not last point. Second to last point. The value or utility, the increasing value doesn’t go on forever. Generally, as more users join, it might go up linearly. It might go exponentially for a while. But they all flatline at a certain point. Nothing goes on forever. It’s a very powerful phenomenon. know the analogies I use like a tree. A tree is actually a very powerful phenomenon. The way the roots go into the ground and they suck water up and therefore the tree can grow higher and then the leaves can reach out wider and catch more sunlight. It’s actually a very powerful effect like a network effect. But trees don’t grow to be 20 miles high. At a certain point it doesn’t work anymore. Other factors overcome it. Same with network effects. None of them go on forever. And last point, network effects can go in the opposite direction just as powerfully as in the positive direction. So people call it inverse network effects or negative network effects. If I stop using Zoom, your Zoom mobile app just got worse. Its value decreased. So then you may decide, well, this isn’t as valuable, I’ll leave. Well that makes it less valuable for somebody else. this flywheel, this feedback loop can be positive or it can go negative. And when it goes negative, it can make companies pretty frantic. You see a decent number of CEOs today, fairly frantically worried about their network effects going in reverse. And with that, let me actually finally get to the point of what are the three network effects I look for. This is pretty standard stuff. Well, two of them are very standard. One of them is more something I talk about. Number one, direct network effect also called a one-sided network effect that’s zoom that’s we chat that’s multiplayer gaming that’s i’m playing world of warcraft as a consumer a player you start playing world of warcraft it’s a multiplayer game i can shoot your guy you can shoot my guy we can chat while we’re playing the more consumers and players of the game the better the game becomes Zoom is the same thing. All the examples I just gave you for Zoom and WeChat, communications are usually one-sided direct network effects. Peer-to-peer payment, I can send you money, you can send me money. Those are all sort of one-sided. I think most people know that. Second one, indirect, also called two-sided network effects. This is your standard marketplace business model. The more consumers on Lazada, the more valuable it is to merchants. The more merchants on Lazada, the more valuable to consumers, but not to each other. If you’re on Lazada and I’m on Lazada, doesn’t help me, doesn’t help you. And when more merchants get on Lazada, not only does it not help them, it actually makes life worse for them because it’s harder and harder for them to get business. The more Uber drivers are out cruising the streets, looking for rides on a Monday morning, the worse it is. So there was this argument for a long time that yes, an indirect network effect can actually become negative at a certain point, especially for merchants, but don’t worry because the overall value is so good that it overcomes that. I don’t think people believe that anymore. I think a lot of people making videos on YouTube trying to sell stuff on Lazada and trying to give you know, give someone a ride in their Uber vehicle on a quiet Sunday, are very aware of how many other drivers are out there. And it’s, it becomes sort of a decaying scenario, a congested network effect. It’s actually a big deal. And the gaming example I gave you basically has direct and indirect. If we’re on Steam or something and we’re on a site with lots of video games, Atari, Nintendo, PS4, that’s a two-sided business model, indirect network effect. The more people making games, the better it is for people who play games. The more people who play games, the better it is for people who develop games. Indirect two-sided network effect. But if those games are also multiplayer, or they have a communication aspect or a gifting aspect or something like that, you also get a direct one-sided network effect at the same time. And I’ve pointed this out when I’m talking about like, Garena. One of the things I really like about Garena, which is the Southeast Asian gaming platform is they very specifically say they are only going to do games. They don’t do casual games. They only want to do games that are multiplayer and the most immersive and interactive games. And they list what they are like, multiplayer, battle, sports, gaming. They specifically list the ones with the potential for the best network effects, indirect and direct. And the last one, the third one is standardization and interoperability network effects. That’s not really great language. Standardization is pretty, you could consider standardization and interoperability as a subtype of a direct network effect if you really want, but I like to bring it out. This is PDF, this is Microsoft Word, this is file formats. The more people that write documents in Word, the more we can share them with each other. The more people who save things in PDF and use it, that way we can send them. The value increases, the more we adopt a standard. The railroad example was like this. They used to make railroads of different gauges where some tracks were six feet, some tracks were five feet wide, and they couldn’t connect with each other. And then at some point, either the Railroad Association or in the case of China, the government just mandated it. All the rail gauges have to be this size. And suddenly all the networks could connect and everyone making rolling stock and engines and cabooses, all their cabooses could work on any of the tracks. See, that’s a standardization effect. Or you could call it an interoperability network effect. I treat that one separately because I think it’s a different case. Anyhow, those are my three. And this is pretty standard. This is not my stuff. A lot of people talk about this. This is just how I break it down. So five types of platform business models. I gave you three types of networks. This is three types of network effects. OK, last bit of theory, and then I’ll go on to Ant Financial. Three or four questions you can ask. These are pretty standard. Are the network effects local, regional, or international? Uber is mostly a local effect. Lots of drivers in Beijing don’t help people in Bangkok get rides on a Sunday. Most marketplace platforms like Lazada, Shopee, Coupang, Amazon, you know, that’s mostly national because most things are shipped national, maybe regional, but it’s not generally international too much. And then you have some international network effects like travel, Ctrip, Expedia. Airbnb have international network effects. That tends to be generally the bigger they are, the more powerful they are, but it depends on the nature of the interaction. You could open lots of Uber sites all over the world. It’s not acting as one network. For it to act as one network, the core activity, the core interaction that you’re enabling has to be international as well. Like I live in Thailand, but I’m looking for a hotel in Brazil. That’s international by the very activity. So that’s one way to think about it. Fast versus slow network effects. You can kind of think about the frequency, the time frame, and then the length of the interaction. If I go to Uber, I don’t know why I keep mentioning Uber. Let’s say DD. If I go to DD, that’s a high frequency activity. But the time frame is not that long. And the length of the interaction between me and the driver that they’re connecting me with is very, very short. I’m not staying in touch with the driver. So compare that to Facebook. There’s a high frequency of interaction. It can go on for a long time. But you stay connected with your social network for years and decades. So the length of the interaction between you and other parts of the network is valuable in that sense. You can bring up, the reason I’m bringing this up is people often talk about universities as having a slow network effect. You know, you go to school, you get your MBA, Columbia Business School, okay fine, you go into recruiting season, you get interviews at Goldman and Morgan and I don’t know, Deloitte and whoever you want. More than likely some of the people you’re interviewing with are graduates of Columbia Business School. Or if not Columbia, a small number of business schools, like 10 of them, they know you. They don’t know you. They know what your brand means, I guess, in their minds. They probably more than likely hire people with similar backgrounds to their own. They get hired. You go, you work there 10, 15 years. Suddenly, it actually doesn’t take that long. It takes like five years to be in the recruiting process. Suddenly, you’re interviewing students. And you’re the Columbia Business School grad who’s now been working at Deloitte for five years, and you’re interviewing people from Wharton, and there tends to be this slow rolling network effect where the more people that go through this and then they go and they get their job, they support the next generation, and it becomes more valuable. I mean, I guarantee you, these companies, these universities, the Harvards and all them, they are not who they are in life because they teach better. The content is pretty much 75% the same. It’s about the network effect. It’s about reputation. It’s about an insurance policy in life. It’s about a lot of things. Content and teaching are actually, they’re on the list, but they ain’t in the top two or three. Last one, think about minimum viable scale. If we’re talking about supply side economies of scale, I want to get into the, I don’t know, beer bottling business. I’m gonna have to build a factory, let’s say in Singapore, because beer is generally a local regional game, and there’s already gonna be a brewery and a bottling facility outside of Singapore that makes, I don’t know, a Singtower, Krohn or whatever. They’re gonna have an economies of scale advantage of me, relative to me, based on they have a higher volume, but our fixed costs are probably the same, so they have a lower per unit cost per bottle of beer. Okay. For me to even get in this game, there’s a minimum viable scale I have to get to where my cost structure is in the same ballpark. Underneath that, I am probably building and operating and not making any money. So often with network, I’m sorry, with economies of scale, we talk about sort of what is the maximum scale before the value sort of flatlines and what is the minimum viable scale to get in this game. And we can see the same thing on the demand side economies of scale, which is a network effect. There’s a minimum viable scale you need to get to before your service has any value. If you’re offering rides on DD, if I have the Jeff mobile app for ride sharing, and you go on there to get a ride home from your office, and the nearest driver is 15 to 20 minutes away, I am non-viable. I don’t have enough scale in my platform. to get you to use my business, you immediately go to Uber or DD and use them. I have to get enough drivers, enough scales, such that maybe the wait is five minutes. Any more than that, people are gonna switch. I have to reach minimum viable scale. And then the next level would be, okay, what is the maximum scale? What is the asthmatotic scale? If I’ve got a thousand drivers in your neighborhood, Eh, you probably only needed 100 to get most of the value. The other 900 aren’t helping anybody. They’re just cruising around. So you kind of want to know minimum viable scale and asthmatotic scale. And you want to look at that against a network effect and decide, are they very low or are they very high? Generally speaking, a high minimum viable scale and a high asthmatotic level means a more powerful network effect. One of Uber’s problems is it’s very low. minimum viable scale. It’s really easy to get into the Uber business. Hire 35 drivers, put them in one little neighborhood, you’re good to go. And having 500 drivers doesn’t help you. So they’re low on the minimum viable and they’re low on the asthmatotic level. Airbnb is super high on both. If you’re gonna offer global housing solutions, you’ve gotta cover at least a region of the world. one country’s probably not going to do it. You probably need to cover all of North and South America or all of Asia just to get in the game. And then as you add more and more, the value keeps going up so it doesn’t asymptote. I’m probably saying that word wrong, Aspintote. It doesn’t really ever Aspintote, it keeps going up linearly. Okay, and one last point. Does it, I already mentioned this, does it increase linearly, exponentially, at what level of value of scale? Anyways, I’m gonna put these questions in the show notes because I know it’s kind of a bit of theory, but it’s a decent list to run and think about. Okay, and last question. My go-to question at the end of the day whenever I’m thinking about a network effect is, how does the marginal, sorry, let me say it again. How does the marginal user or activity increase the value and or utility to users? It’s the marginal user. It’s the marginal level of activity. How much does that increase value? And that’s why a company like Airbnb is so powerful because it’s highly differentiated. It’s not a commodity service like One More Rider. It’s very hard to add marginal value. I’m sorry, it’s very hard to add increased value with just a marginal amount of the same exact service. We have 50 drivers all offering the same commodity service. Now we have 51. Hotels, living, short-term stay, big houses on the beach, houses for families, downtown condos. When you add a new type of housing, they’re all differentiated. So every new type of housing, every marginal user activity, adds more value because the value is pretty differentiated. So anyways, OK, let me get into Ant. Now, Ant Financial, which used to be called Alipay, then it became Ant Financial, and then it became Ant Group. And now I think I just call it Ant in their filing. Interesting business. It’s what I would call a complementary platform. If you look at my. pyramid for sort of competitive strength, the very top of the pyramid I call competitive fortresses. And there’s only a couple types of businesses, I think, that really make it to that we’re untouchable point. Like the NBA is there. Tencent is there. And I think Ant Financial is there. And I put that category as what I call complementary platforms. We don’t have one platform business model. We don’t have two. We have several. that reinforce and help each other, which can be very, very powerful. Now, Ant is kind of a quirky version of this because when they went public, their explanation didn’t make a whole lot of sense. In fact, I think the language was kind of confusing. In literally the first paragraph of their filing, they said that they are basically a super app. Our mobile app, Alipay, is a ubiquitous super app that draws together over 1 billion users. Okay now super app is kind of a weird phrase. They say but our super app offers payment, digital finance, and daily life services. Those are their kind of three phrases. Okay but then literally in the second paragraph, right below it, it says We are a one-stop shop for digital payment and digital finance services, including credit, investment, and insurance. So they were kind of talking out of both sides of their mouths. They were saying, we’re a super app. We’re a consumer-facing super app. Services, payment, things like that. But then they would switch and say, oh, we’re also sort of a digital finance super shop, a one-stop shop for digital finance services. OK, well those are kind of two different things. And they put together a graphic. I’ll put it in the show notes. When I say show notes, if it’s a JPEG or something like that, it’s usually on my website, but it’s not in the iTunes one. But they have a graphic for how they explain all this. Investment tech, credit tech, insurance tech, daily digital life, local services, mobility services. I don’t understand this graphic at all. You know, it’s something that the bankers put together to explain them. I totally don’t get it. I really wish they would have called me. I would have given them, I think, not to pat myself on the back, but I would have given them a much better picture for how to describe what they’re doing. And I’ve actually done that before. I was talking with Alibaba.com, the B2B business between, mostly the US and China where they were connecting Chinese factories with, um, US small and medium size merchants. And they’re explaining all these services they do and how if you’re a small company in the US, you can basically buy things from China or India or wherever. And they’ll handle all the transit, all the payment, the escrow, getting through customs, the contracting, all of that. That’s what we’re doing. And they kept explaining all their solutions. And I kind of said, so you’re basically letting SMEs do what MNCs can do. You’re letting small businesses act like multinationals. And they’re like, yeah, and I swear to God, like a month later, I heard them using my phrase in their description of what they’re doing in the press. And they never gave me credit, but it was totally for me, I think. Anyways, the way I would describe what Ant is, is it’s three complimentary platforms that all strengthen each other. Platform number one, payment platform. This is one of my five platform business model types. They aren’t mine, but I mean, people say these, but I’m referring to. the five I list. Merchants on one side, that’s one user group, consumers on another. The purpose of the platform is to enable interactions, which are payments, and they can be consumer to consumer, which we call a direct network effect, and they can be consumer to merchant, which we call an indirect network effect, and they can even be merchant to merchant, which would be another direct network effect. Okay. That’s the platform business model. I’m saying it has three types of network effects. What is the network that enables this? What is the asset? Well, I mean, it’s people, right? That’s really what we’re connecting. We’re connecting people and companies. Those are the nodes of the network and then the linkages connect them. You could point to the smartphones they’re using or the POS terminals as a protocol network, but really we’re talking about a people network or a people and company network. Okay. That’s how I described that one. And Alibaba pretty much describes their payment platform as infrastructure. That this is the foundation. And this is probably the most powerful network. I’m sorry, the most powerful mechanism to grow the network, the asset. Because all of their other businesses require a network, a people network. So what is it that you’re doing that’s going to enable the people network to grow? Now Mark Zuckerberg, he does that by messenger and social interactions. By providing social interactions, he’s grown a massive social network. Well payment turns out to be a fairly powerful way of growing your network. Because if I want to send you $5, you have to sign up. And therefore you have joined the network. The virality of payment makes it a powerful way to grow the network of people. Now it’s also a good way to make some money because it turns out doing payment is fairly profitable but when I look at the payment platform that to me looks like the foundation of how they’re growing the network. Okay platform type two. They have a marketplace for high frequency B2C services. So a marketplace platform but not merchants selling products instead it’s service businesses selling things like. hotel reservations, get your food delivered. This is basically Meituan. And Ulema, which is the competitor to Meituan, was moved under Alipay, like at the beginning of 2020. So it became part of Alipay about a year and a half ago. Okay, why is that valuable? All right, we have a marketplace platform for services that are high frequency. Do we have a network effect? Yeah, we have an indirect network effect between merchants and consumers. The more merchants, the more valuable to consumers and vice versa. So we have an indirect network effect. We have a marketplace platform for high frequency B2C services. And the network it is using, the network type, the asset is basically the same one as the payment platform. So when I look at the payment platform, I see a very powerful way to build a network. When I look at the marketplace for services, buying dinner, getting movie tickets, I see a powerful mechanism for increasing engagement. Because these are the services people use on a daily basis, which is why Alibaba calls them daily life services. It’s not that great of a way to grow a network. It doesn’t make you that much money. The network effects are pretty good, but to me it’s the frequency of engagement that you’re really getting from the second platform. Third one, last platform. They have a marketplace platform for financial services. On one side of the network, I’m sorry, one side of the platform, they have the same consumer group. On the other side of the platform, they have a second user group, which is banks, insurance companies, asset management companies, people offering wealth management products, and they are doing matching, it’s a marketplace. You wanna borrow some money? We connect you with bank number A. they extend the loan, you get credit, consumer credit. You want to buy an insurance policy, we connect you with so-and-so insurance company. You want to invest some money in a mutual fund. So it’s a marketplace. But think about that marketplace on its own. If you wanted to build that as a standalone business, could you do it? You’d have to get a network. All right, you’d have to sign up a lot of banks. You’d have to sign up a lot of asset management companies. You’d have to sign up a lot of insurance companies. I don’t think it would be viable as a standalone marketplace. People don’t buy insurance every day. They might buy once a year. People don’t borrow money, although they borrow money more than they buy insurance. They don’t buy investment products. The frequency is incredibly low. So it would be very hard to see how that would stand apart and stand alone. What I do like about that platform is it’s a powerful way to make money. Because when someone invests $20,000 in a mutual fund or an asset, that’s a lot more money than sending $1. Right? So you have low frequency, but you have very big potential money. And at the time of the IPO for Ant, the big sources of revenue were really coming from payment, you take a little fee every time someone makes a payment, and they were coming from consumer and supplier credit. That’s where the money was coming from. So you kind of need at least two of those platforms, if not all three, to make them work. The payment platform gets you the network, you get some engagement, and you make some money. The marketplace for services, local services, That really gets you engagement, but the money is actually pretty small. The marketplace for financial services doesn’t have any frequency, but it’s potentially the biggest dollars long term. And that only works if it’s all three of them sitting on top of each other, i.e. three complementary platforms. They share a common network, but they do have different platform types and different network effects on all of them. Does that make sense? I know I’m speeding up as I’m speaking here because I’m going long, I’m trying to finish up. But I think that’s a good way to think about it. And I think when you start looking at these things, if you can break them down by network effect as a phenomenon, platform as a business model type, and then the network itself as an asset, I think you can start to take apart these things in a more thoughtful way. Because usually when people talk about Ant and Alibaba, they start to use these general terms like Well, it’s an ecosystem. I don’t really know what that means. Well, it’s a digital economy. Okay, I don’t know what that means either. It’s a conglomerate. It’s a digital conglomerate. I think this is all fuzzy thinking. If you take it apart the way I just did, look, you know, networks, platform business models, network effects. We take apart each of these phenomenon together and we get three different platforms with multiple network effects and one. I mean, you actually get a very detailed picture of what this company is doing. And then you can also map out the linkages between the platforms and how they help each other. And so I wouldn’t just call that, oh, it’s a digital economy. No, I think that’s a fairly detailed description of the mechanics of what is actually going on. And that’s what I’m trying to do, to break these things down into components, and then add them up and see how they all fit together like a machine. OK, and I think that is it for content for today. The three concepts, once again, networks versus platforms, direct and indirect network effects, standardization and interconnection network effects, or interoperability network effects. And the company for today was Ant Financial. If you ever want to go back on these things, just click on the company library, and you can scroll down and find Ant, and you’ll find all my articles and podcasts on Ant. or you can go to the concept library scroll down and click on any of these ideas concepts and same thing okay as for me i am still here in mexico city i’ve got a couple more days here and then i’m going down to rio de gionero for a month actually five weeks i was supposed to fly back to uh thailand in about a week and i basically gave up on that it was just um it’s too complicated It’s the rules are changing. There’s a new sandbox policy going in on July 1st, which was like two to three days before my flight. And they’re basically turning Phuket into a big quarantine where you can fly to Phuket and you have to stay there for 14 days, but you don’t have to be in your room like in Bangkok. As long as you’re on the island, you’re good to go, which is a pretty cool idea. I mean, it’s kind of a crazy idea if you think about it. I’m really curious, I want to know the person who thought that up. Like, how do we, how do we restart the tourism industry without exposing the country? Why don’t we just turn the big massive island, which is the number one tourist destination in terms of beaches. Why don’t we just turn the whole island into a quarantine and we’ll vaccinate everybody on the island. Um, we’ll, you know, we’ll, we’ll block the bridges, we’ll block the airport, we’ll block the boats. and then people can just fly in, have their vacation, and do their normal Phuket stuff and after 14 days then we’ll let them go to the rest of the country. I mean that’s super clever as an idea. It’s really crazy. Like is there any other country in the world that’s doing anything like this? Is Hawaii just like quarantining one island and you can fly there? Or Manhattan? Okay, everyone in Manhattan you’re free to fly in but you can’t leave the island for 14 days. I mean, it’s a crazy idea, but they’re rolling it out. It starts July 1st. I was gonna try and go for it, but it’s actually kind of complicated. Like I literally had to make a spreadsheet of how to get where I needed to go. It was really complicated. Like you have to fly from Mexico to the US, but that means I need a COVID test to get on the plane, but I don’t need a PCR COVID test. I need a rapid antigen test, which is different. And then when you get there, you have to do a certificate of entry to get to Thailand, but to apply to certificate of entry, which is like just another form, which you do through the embassy, you have to meet certain criteria like, I have a work permit, so I can use that criteria. The Phuket sandbox is not listed as one of the criteria you can apply for a certificate of entry yet. It’s supposed to go up like today or tomorrow. So it’s all sort of happening in real time and I eventually decided it was too complicated and I was going to fly to Bangkok and then you could get a connecting flight to Phuket but only if they’ve got the new terminal that’s isolated set up by the first. There’s all this crazy stuff. Anyways, I just threw in the towel and said, all right, I’m going to Rio for a month and I’m going to rent a WeWork space or something like that and You know, just spend my month in the gym and on the beach and I’m finishing up this book which is as of this morning is 115,000 words. That’s crazy. Like a normal book is 80,000 words, 70,000 words. I’m already at 115,000 which I’ve cranked out over the past three weeks. And I’ve probably got another 30 to 40,000 to go. This thing’s out of control. Anyways, I’m going to try and finish that up. and be all done with it. So it should be a pretty awesome month. I absolutely love being in Rio. Just as a general sort of gift to myself in life, I’ve been spending one to two months per year in Rio. I don’t really do any business there. I give talks every now and then, probably not this year, but I just go because I enjoy it so much. I haven’t done it in a year and a half, so anyways, that’s going to be my month. It should be great. I’ll send, maybe I’ll do some videos from there. I used to do videos, I haven’t done them in a year. I might start doing that. But anyways, we’ll see if we can record one of these podcasts from the beach in Leblon. If anyone’s listening in Rio, give me a call. I’m usually hanging out in Leblon, that’s my little neighborhood. But yeah, it’s gonna be great. Anyways, that’s all I got. I hope everyone is doing well. I hope this was helpful. And if you have any suggestions for companies to look at, I’m gonna shift back to companies. I should have done that last week, but. I got buried in this book, but I’ll be back more in companies this week. But if you have any suggestions, let me know. Other than that, take care and I will talk to you next week. Bye bye.